Policy Brief: Property Tax Relief (Circuit Breaker)

March 5, 2015 |

March 5, 2015. The property tax relief plan (circuit breaker) proposed by the governor would help low- and middle-income New Yorkers that are struggling to pay their taxes and should be adopted with a few changes that would make it even more effective.

The governor’s Executive Budget proposal includes a significant new property tax “circuit breaker” that would provide relief to households whose property taxes are unreasonably high relative to their income. Currently, 33 states and the District of Columbia provide some type of property tax circuit breaker relief to their taxpayers. Circuit breakers would address a serious shortcoming of the property tax—that payments are not linked to the taxpayers’ ability to pay.

Some modifications the legislature should consider include:

- Eliminating a provision that makes homeowners and renters eligible for refunds only if they live in jurisdictions that comply with the state’s property tax cap law.

- Boosting the size of the credits to provide a sufficient level of relief.

- Minimizing the cost of any expansion by considering the use of a broader measure of income to determine whether a household is eligible for the credit or limiting the amount of the credit for owners of very high-valued homes, design features recommended by the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. Increasing the minimum amount of time a person has to have lived in their home to qualify for a refund is another option.

- Covering the cost of the property tax relief through the reform or elimination of unnecessary tax breaks for businesses and high-income individuals, rather than through an arbitrary limit on state spending that harms New York’s economy.

Why a circuit breaker is needed.

Local governments in New York and elsewhere rely on the property tax to pay for important services such as education, transportation, and health care. Funding local services with the property tax carries some advantages. For example, it is a relatively stable revenue source that generally grows as needs grow, when population and the local economy expand. In addition, the property tax gives residents local control over funding and service levels.

But property taxes bring major equity problems. The amount of property taxes owed is not tied directly to a household’s ability to pay. As a result, many individuals and families in New York pay an unsustainably large share of their income in property taxes.

One group of taxpayers for whom residential property taxes are often high relative to income are those with low and moderate incomes. This includes:

- Families who live in areas where income has stagnated in recent decades, during the period when the state has reduced its contribution to jointly funded services, forcing localities to rely more heavily on the property tax than they did in the past.

- Families who live in areas with high housing costs, since property taxes within a given community tend to be roughly proportionate to housing costs.

- Renters—who are disproportionately represented among low-income families—as landlords generally pass on a substantial share of their property taxes in the form of higher rent.

- The more than 700,000 households with incomes below $100,000 who have lived in their homes for more than five years and pay more than 10 percent of income in property taxes. This includes close to two-thirds of households with income of $25,000 or less.[1]

- The nearly 240,000 households in New York with incomes below $50,000 a year who pay more than 20 percent of their income in property taxes.[2]

A second group of taxpayers who may struggle to afford property taxes are those who rely primarily on fixed incomes living in places where property values—and thus property tax assessments—have risen rapidly, for instance a senior citizen who has lived in the same home for decades. This will be a growing problem for many other people as housing values begin to recover from the recession but incomes remain stagnant.

A third group of homeowners whose property taxes may be high relative to income, at least temporarily, are those with a sudden decline in income—for example, the newly unemployed.

How the proposed circuit breaker would work.

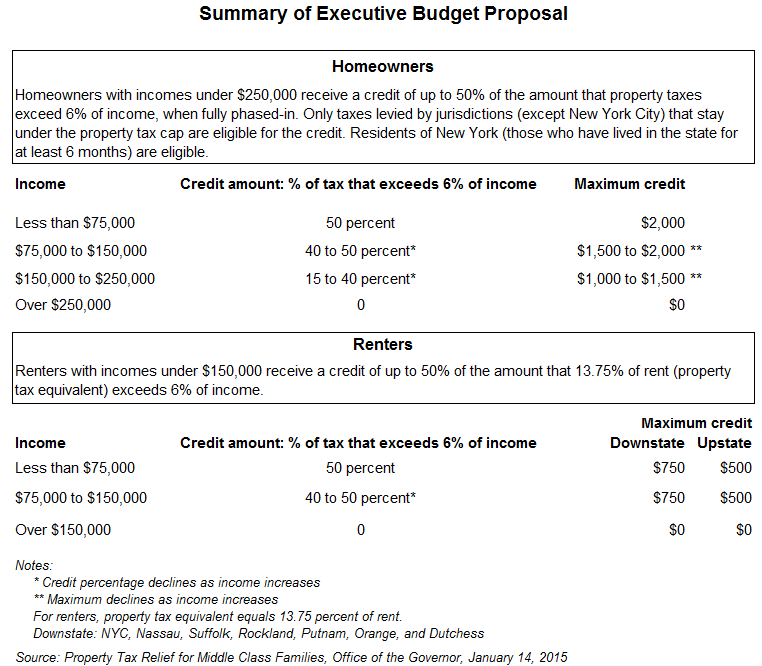

Property tax circuit breakers can address these and similar problems by providing tax refunds based on annual income—often using information from income tax returns—and property tax bills. Under the Executive Budget proposal, homeowners with incomes under $250,000 would receive a credit of up to 50 percent of the amount that property taxes exceed 6 percent of income. For example, a family making $50,000 per year and paying $6,000 annually in property taxes would see a $1,500 annual credit—or a 25 percent reduction in property taxes.

Renters with incomes under $150,000 would get a credit based on the property taxes built into their rent. The credit would be up to 50 percent of the amount of the property tax—estimated at 13.75 percent of rent—that exceeds 6 percent of income. For example, a renter who makes $40,000 a year and pays $2,000 per month in rent would get a credit of $450. This equals 50 percent of the amount that $3,300 (13.75 percent of annual rent of $24,000) exceeds $2,400 (6 percent of income). See “Summary of Executive Budget Proposal” after the “Conclusion”.

When fully phased in by 2018, more than 1.3 million New York homeowners would get credits that average $950. Over 1 million renters would get credits based on the property taxes included in their rent that average $400. The program would reduce state income tax revenues by $1.66 billion when fully phased-in.[3]

Low- and moderate-income taxpayers would be the biggest beneficiaries.

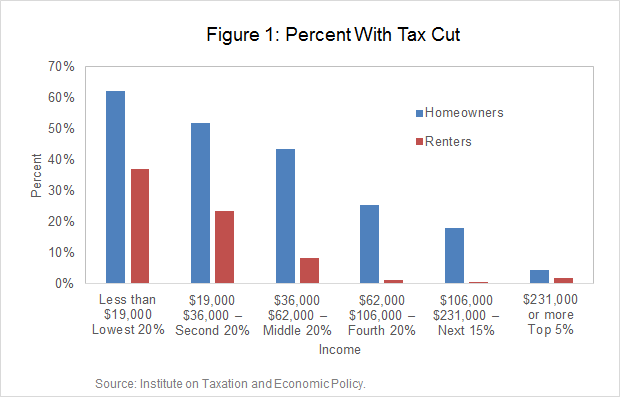

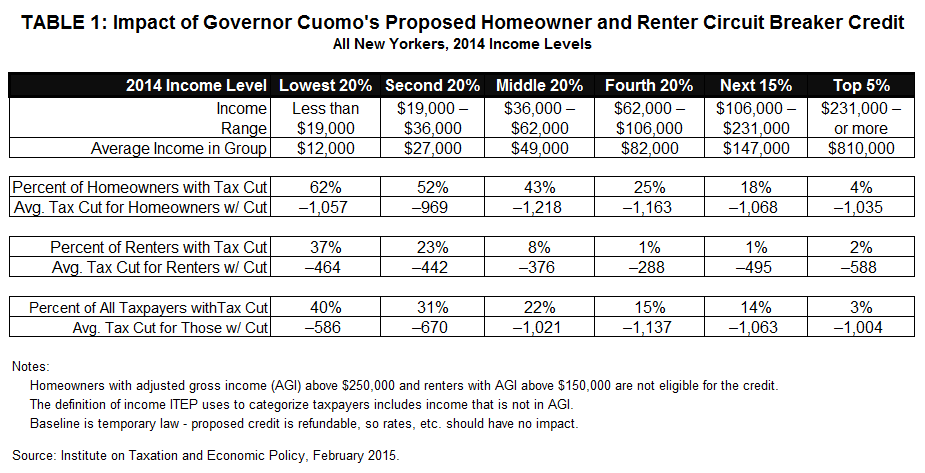

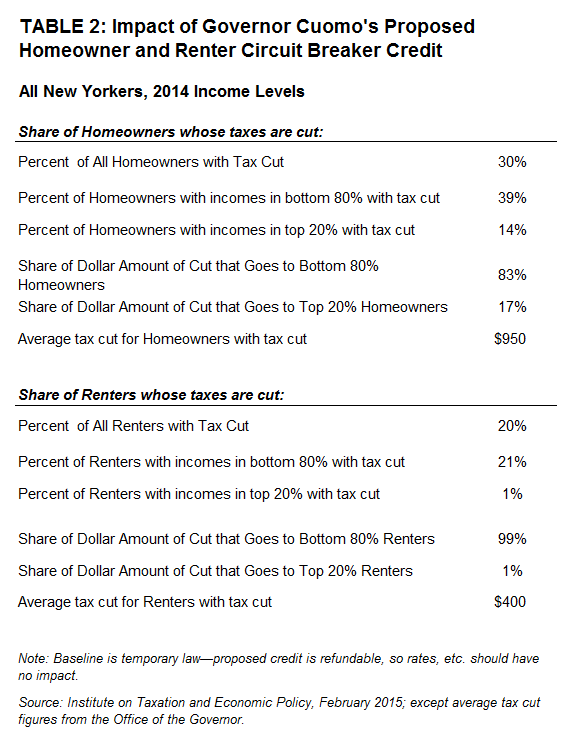

Those at the bottom of the income scale would benefit most—62 percent of homeowners and 37 percent of renters with incomes below $19,000 would receive a circuit breaker refund according to an analysis of the governor’s proposal by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. Some 27 percent of homeowners and renters with incomes below $106,000 (80 percent of all incomes in New York) would receive a tax cut. Just 12 percent of those earning $106,000 or more—the top 20 percent—would get a refund.[4] See Figure 1 and the tables in the appendix for more details.

Property tax payers across New York would benefit.

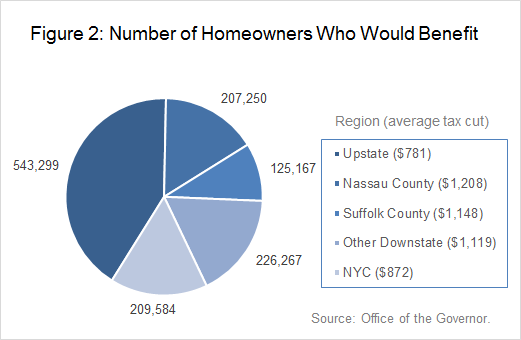

Figures 2 and 3 show beneficiaries and average credits by region based on data from the Office of the Governor.[5] Homeowners in all parts of the state would get tax relief. The average credits would be largest for those downstate because of the high property taxes relative to income there. For example, more than 330,000 homeowners in the two Long Island counties of Nassau and Suffolk would receive credits averaging $1,186—some 25 percent higher than the statewide average.

Ways to improve the circuit breaker

The proposed circuit breaker is a good idea but it could be improved. Some changes that the state should consider include:

Removing the link to the property tax cap. One of the most problematic features of the Executive Budget proposal is that homeowners and renters are only eligible for credits for property taxes levied by jurisdictions that are in compliance with the state’s property tax cap law. Under the provisions of the property tax cap law passed in 2011 localities are not permitted to raise property taxes by more than 2 percent or the rate of inflation, whichever is lower (with some exceptions). Localities are allowed to override the limit either through a supermajority (60 percent) vote of taxpayers (for school districts) or of the governing body (for cities and counties). The override rules allow localities to decide whether higher property taxes are acceptable to finance specific needs. In general, higher wealth localities have been more likely to pass overrides.

However, there are pockets of low- and moderate-income households even in the wealthiest localities. These residents may not be able to influence the override votes but will still be required to pay property taxes at a level that may be a significant share of their incomes. The state should not deny needed property tax credits to these homeowners and renters simply because their neighbors desire and are able to afford higher taxes to pay for services. In theory, tying the circuit breaker refunds to compliance with the cap could make it harder for localities to override the cap since residents who would lose the benefit of the circuit breaker would oppose the override. But in reality, it is unlikely that the linkage will be a major factor in such decisions. The circuit breaker refunds are paid in the year following payment of the property taxes owed so taxpayers must come up with money to pay the tax up front. And, the proposed circuit breaker only reduces taxes above a certain level by fifty percent. It does not eliminate all property taxes owed.

Increasing the size of the credits. The effectiveness of the credit would be improved by raising the maximum credit amount. There are many areas of the state where homeowners will face a steep property tax bill even after a $2,000 credit. Increasing the percentage of taxes offset by the credit would also assist more renters and homeowners.

Renters, in particular, face difficulties paying for housing. The median income of renters in New York is less than half that of homeowners.[6] The renters credit could be increased by raising the percentage used to determine the share of rent that constitutes property taxes from 13.75 percent to one that better reflects costs in New York. Property taxes make up almost 30 percent of the costs of New York City apartments according to the most recent report of the New York City Rent Guidelines Board.[7] The majority of New Yorkers who would receive the renters credit live in New York City.

Considering Other Changes to the Design of the Credit. Providing more tax relief by increasing the credit amounts would make the program more costly. This increased cost could be offset, however, by considering design feature changes that would reduce the cost such as:

- Broadening the income definition. The circuit breaker uses adjusted gross income as defined in the personal income tax to determine whether a household is eligible for the credit and the size of their credit. This income definition excludes some sources of income that are not taxable but that do contribute to a taxpayers’ ability to pay property taxes, such as interest from tax-exempt bonds and Social Security payments. A broad definition of income is recommended by many experts in circuit breaker design.[8] New York’s existing circuit breaker for low-income taxpayers uses household gross income—a broader definition of income than adjusted gross income. Because the credits would be better targeted to those most in need, using a broader definition of income would lower the cost of the program.[9]

- Including an asset test. Limiting tax relief to the tax on the portion of home value below a set ceiling avoids making large payments to people with very expensive homes. They are more able to borrow against the equity in their houses to meet expenses. The limit could be set at a multiple of the median home value in the state such as twice ($576,400) the statewide median value.[10]

- Increasing the residency requirement. As proposed, the credit would be available to all New York residents who have lived in their homes for at least 6 months. This short residency requirement could result in new residents purchasing homes that are more expensive than they could otherwise afford, which is not the purpose of the credit. Extending the time required to be eligible for the credit would address this problem and also reduce the cost of the program.

Replacing the revenue lost. According to the Executive Budget, the future cost of the credit will be covered with surplus funds generated by the state’s adherence to the overall 2 percent cap on spending increases in future years. This self-imposed and unnecessary austerity leaves New York unable to invest enough in education and poverty reduction, as FPI discusses in its budget briefing book.[11] Rather than limit investment in other needed services to pay for the circuit breaker, the state should generate additional revenues by fixing some of the problems related to last year’s corporate tax reform, eliminating or scaling back many of the state’s smorgasbord of business tax credits, rejecting the proposed Education Tax Credit, and limiting the increase in the estate tax exemption.

Conclusion

As welcome as the circuit breaker is, it will not solve the fundamental problem that is causing high property taxes in New York: the state’s failure to be a reliable partner to localities in shouldering the cost of education, healthcare, transportation, and other services. This failure is one of the major reasons for higher-than-average property taxes in New York.

Until these long-term problems are addressed, enacting the property tax circuit breaker (with or without the improvements suggested above) would provide much needed assistance to those who struggle the hardest to afford property taxes.

APPENDIX

PDF of Property Tax Relief Brief

[1] FPI analysis of 2011 American Community Survey data.

[2] FPI analysis of 2011 American Community Survey data.

[3] FY 2015-16 Executive Budget and various press releases from the Office of the Governor.

[4] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy analysis, February 2015.

[5] Property Tax Relief for Middle Class Families, Office of the Governor, January 14, 2015.

[6] According to the most recent American Community Survey data from the Census, the median income of homeowners in New York State is $79,750 while the median income of renters is $36,805.

[7] 2014 Price Index of Operating Costs, New York City Rent Guidelines Board, April 24, 2014.

[8] See, for example, Property Tax Circuit breakers: Fair and Cost-Effective Relief for Taxpayers, Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, 2009.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Per the Census American Community Survey, 2009-13 median home value in New York was $288,200.

[11] Fiscal Policy Institute, A Shared Opportunity Agenda, February 10, 2015.

Policy Brief: Property Tax Relief (Circuit Breaker)

March 5, 2015 |

March 5, 2015. The property tax relief plan (circuit breaker) proposed by the governor would help low- and middle-income New Yorkers that are struggling to pay their taxes and should be adopted with a few changes that would make it even more effective.

The governor’s Executive Budget proposal includes a significant new property tax “circuit breaker” that would provide relief to households whose property taxes are unreasonably high relative to their income. Currently, 33 states and the District of Columbia provide some type of property tax circuit breaker relief to their taxpayers. Circuit breakers would address a serious shortcoming of the property tax—that payments are not linked to the taxpayers’ ability to pay.

Some modifications the legislature should consider include:

- Eliminating a provision that makes homeowners and renters eligible for refunds only if they live in jurisdictions that comply with the state’s property tax cap law.

- Boosting the size of the credits to provide a sufficient level of relief.

- Minimizing the cost of any expansion by considering the use of a broader measure of income to determine whether a household is eligible for the credit or limiting the amount of the credit for owners of very high-valued homes, design features recommended by the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. Increasing the minimum amount of time a person has to have lived in their home to qualify for a refund is another option.

- Covering the cost of the property tax relief through the reform or elimination of unnecessary tax breaks for businesses and high-income individuals, rather than through an arbitrary limit on state spending that harms New York’s economy.

Why a circuit breaker is needed.

Local governments in New York and elsewhere rely on the property tax to pay for important services such as education, transportation, and health care. Funding local services with the property tax carries some advantages. For example, it is a relatively stable revenue source that generally grows as needs grow, when population and the local economy expand. In addition, the property tax gives residents local control over funding and service levels.

But property taxes bring major equity problems. The amount of property taxes owed is not tied directly to a household’s ability to pay. As a result, many individuals and families in New York pay an unsustainably large share of their income in property taxes.

One group of taxpayers for whom residential property taxes are often high relative to income are those with low and moderate incomes. This includes:

- Families who live in areas where income has stagnated in recent decades, during the period when the state has reduced its contribution to jointly funded services, forcing localities to rely more heavily on the property tax than they did in the past.

- Families who live in areas with high housing costs, since property taxes within a given community tend to be roughly proportionate to housing costs.

- Renters—who are disproportionately represented among low-income families—as landlords generally pass on a substantial share of their property taxes in the form of higher rent.

- The more than 700,000 households with incomes below $100,000 who have lived in their homes for more than five years and pay more than 10 percent of income in property taxes. This includes close to two-thirds of households with income of $25,000 or less.[1]

- The nearly 240,000 households in New York with incomes below $50,000 a year who pay more than 20 percent of their income in property taxes.[2]

A second group of taxpayers who may struggle to afford property taxes are those who rely primarily on fixed incomes living in places where property values—and thus property tax assessments—have risen rapidly, for instance a senior citizen who has lived in the same home for decades. This will be a growing problem for many other people as housing values begin to recover from the recession but incomes remain stagnant.

A third group of homeowners whose property taxes may be high relative to income, at least temporarily, are those with a sudden decline in income—for example, the newly unemployed.

How the proposed circuit breaker would work.

Property tax circuit breakers can address these and similar problems by providing tax refunds based on annual income—often using information from income tax returns—and property tax bills. Under the Executive Budget proposal, homeowners with incomes under $250,000 would receive a credit of up to 50 percent of the amount that property taxes exceed 6 percent of income. For example, a family making $50,000 per year and paying $6,000 annually in property taxes would see a $1,500 annual credit—or a 25 percent reduction in property taxes.

Renters with incomes under $150,000 would get a credit based on the property taxes built into their rent. The credit would be up to 50 percent of the amount of the property tax—estimated at 13.75 percent of rent—that exceeds 6 percent of income. For example, a renter who makes $40,000 a year and pays $2,000 per month in rent would get a credit of $450. This equals 50 percent of the amount that $3,300 (13.75 percent of annual rent of $24,000) exceeds $2,400 (6 percent of income). See “Summary of Executive Budget Proposal” after the “Conclusion”.

When fully phased in by 2018, more than 1.3 million New York homeowners would get credits that average $950. Over 1 million renters would get credits based on the property taxes included in their rent that average $400. The program would reduce state income tax revenues by $1.66 billion when fully phased-in.[3]

Low- and moderate-income taxpayers would be the biggest beneficiaries.

Those at the bottom of the income scale would benefit most—62 percent of homeowners and 37 percent of renters with incomes below $19,000 would receive a circuit breaker refund according to an analysis of the governor’s proposal by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. Some 27 percent of homeowners and renters with incomes below $106,000 (80 percent of all incomes in New York) would receive a tax cut. Just 12 percent of those earning $106,000 or more—the top 20 percent—would get a refund.[4] See Figure 1 and the tables in the appendix for more details.

Property tax payers across New York would benefit.

Figures 2 and 3 show beneficiaries and average credits by region based on data from the Office of the Governor.[5] Homeowners in all parts of the state would get tax relief. The average credits would be largest for those downstate because of the high property taxes relative to income there. For example, more than 330,000 homeowners in the two Long Island counties of Nassau and Suffolk would receive credits averaging $1,186—some 25 percent higher than the statewide average.

Ways to improve the circuit breaker

The proposed circuit breaker is a good idea but it could be improved. Some changes that the state should consider include:

Removing the link to the property tax cap. One of the most problematic features of the Executive Budget proposal is that homeowners and renters are only eligible for credits for property taxes levied by jurisdictions that are in compliance with the state’s property tax cap law. Under the provisions of the property tax cap law passed in 2011 localities are not permitted to raise property taxes by more than 2 percent or the rate of inflation, whichever is lower (with some exceptions). Localities are allowed to override the limit either through a supermajority (60 percent) vote of taxpayers (for school districts) or of the governing body (for cities and counties). The override rules allow localities to decide whether higher property taxes are acceptable to finance specific needs. In general, higher wealth localities have been more likely to pass overrides.

However, there are pockets of low- and moderate-income households even in the wealthiest localities. These residents may not be able to influence the override votes but will still be required to pay property taxes at a level that may be a significant share of their incomes. The state should not deny needed property tax credits to these homeowners and renters simply because their neighbors desire and are able to afford higher taxes to pay for services. In theory, tying the circuit breaker refunds to compliance with the cap could make it harder for localities to override the cap since residents who would lose the benefit of the circuit breaker would oppose the override. But in reality, it is unlikely that the linkage will be a major factor in such decisions. The circuit breaker refunds are paid in the year following payment of the property taxes owed so taxpayers must come up with money to pay the tax up front. And, the proposed circuit breaker only reduces taxes above a certain level by fifty percent. It does not eliminate all property taxes owed.

Increasing the size of the credits. The effectiveness of the credit would be improved by raising the maximum credit amount. There are many areas of the state where homeowners will face a steep property tax bill even after a $2,000 credit. Increasing the percentage of taxes offset by the credit would also assist more renters and homeowners.

Renters, in particular, face difficulties paying for housing. The median income of renters in New York is less than half that of homeowners.[6] The renters credit could be increased by raising the percentage used to determine the share of rent that constitutes property taxes from 13.75 percent to one that better reflects costs in New York. Property taxes make up almost 30 percent of the costs of New York City apartments according to the most recent report of the New York City Rent Guidelines Board.[7] The majority of New Yorkers who would receive the renters credit live in New York City.

Considering Other Changes to the Design of the Credit. Providing more tax relief by increasing the credit amounts would make the program more costly. This increased cost could be offset, however, by considering design feature changes that would reduce the cost such as:

- Broadening the income definition. The circuit breaker uses adjusted gross income as defined in the personal income tax to determine whether a household is eligible for the credit and the size of their credit. This income definition excludes some sources of income that are not taxable but that do contribute to a taxpayers’ ability to pay property taxes, such as interest from tax-exempt bonds and Social Security payments. A broad definition of income is recommended by many experts in circuit breaker design.[8] New York’s existing circuit breaker for low-income taxpayers uses household gross income—a broader definition of income than adjusted gross income. Because the credits would be better targeted to those most in need, using a broader definition of income would lower the cost of the program.[9]

- Including an asset test. Limiting tax relief to the tax on the portion of home value below a set ceiling avoids making large payments to people with very expensive homes. They are more able to borrow against the equity in their houses to meet expenses. The limit could be set at a multiple of the median home value in the state such as twice ($576,400) the statewide median value.[10]

- Increasing the residency requirement. As proposed, the credit would be available to all New York residents who have lived in their homes for at least 6 months. This short residency requirement could result in new residents purchasing homes that are more expensive than they could otherwise afford, which is not the purpose of the credit. Extending the time required to be eligible for the credit would address this problem and also reduce the cost of the program.

Replacing the revenue lost. According to the Executive Budget, the future cost of the credit will be covered with surplus funds generated by the state’s adherence to the overall 2 percent cap on spending increases in future years. This self-imposed and unnecessary austerity leaves New York unable to invest enough in education and poverty reduction, as FPI discusses in its budget briefing book.[11] Rather than limit investment in other needed services to pay for the circuit breaker, the state should generate additional revenues by fixing some of the problems related to last year’s corporate tax reform, eliminating or scaling back many of the state’s smorgasbord of business tax credits, rejecting the proposed Education Tax Credit, and limiting the increase in the estate tax exemption.

Conclusion

As welcome as the circuit breaker is, it will not solve the fundamental problem that is causing high property taxes in New York: the state’s failure to be a reliable partner to localities in shouldering the cost of education, healthcare, transportation, and other services. This failure is one of the major reasons for higher-than-average property taxes in New York.

Until these long-term problems are addressed, enacting the property tax circuit breaker (with or without the improvements suggested above) would provide much needed assistance to those who struggle the hardest to afford property taxes.

APPENDIX

PDF of Property Tax Relief Brief

[1] FPI analysis of 2011 American Community Survey data.

[2] FPI analysis of 2011 American Community Survey data.

[3] FY 2015-16 Executive Budget and various press releases from the Office of the Governor.

[4] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy analysis, February 2015.

[5] Property Tax Relief for Middle Class Families, Office of the Governor, January 14, 2015.

[6] According to the most recent American Community Survey data from the Census, the median income of homeowners in New York State is $79,750 while the median income of renters is $36,805.

[7] 2014 Price Index of Operating Costs, New York City Rent Guidelines Board, April 24, 2014.

[8] See, for example, Property Tax Circuit breakers: Fair and Cost-Effective Relief for Taxpayers, Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, 2009.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Per the Census American Community Survey, 2009-13 median home value in New York was $288,200.

[11] Fiscal Policy Institute, A Shared Opportunity Agenda, February 10, 2015.