How Fast is New York’s Home Care Program Growing?

December 12, 2024 |

Key Findings

- Much recent reporting has focused on the growth of CDPAP in isolation, but this perspective exaggerates home care growth by ignoring the role of agency-model home care, which accounts for 44 percent of all Medicaid-funded home care in New York.

- CDPAP growth reflects in part the shift of consumers to CDPAP from agency-based home care. Agency-model home care utilization has declined by 19% since 2018.

- Total home care utilization (including both CDPAP and agency models) has increased by just 3.9% per year in the past six years, not much faster than overall growth of the state’s older adult population.

Introduction

The Consumer-Directed Personal Assistance Program (CDPAP) is at the heart of recent debates over Medicaid spending in New York State. Advocates argue that the program, which provides home care for 250,000 Medicaid-enrolled New Yorkers at a cost of roughly $6 billion per year, is critical to the health and independence of elderly and disabled state residents.[1] Critics argue that it’s too expensive and growing too fast, and that it may be subject to abuse. Indeed, Governor Hochul has described the program as “a racket” and proposed massive cuts to the program in her FY 2025 Executive Budget.[2] The legislature rejected most of those cuts, agreeing instead to a major change in how the program works; starting this year, the State will contract with a single fiscal intermediary (FI) to administer the program, replacing hundreds of FIs across the state. However, this change is controversial, and debate over the program will likely continue.[3]

At the heart of this debate is the question of CDPAP growth. New York State Budget Director Blake Washington said during last year’s budget debate that CDPAP has grown more than 1,200 percent over the past decade—a striking figure that has been cited frequently in press coverage of the program.[4] It is certainly true that CDPAP has grown dramatically, but to take this number in isolation is misleading. CDPAP is one of two types of home care offered by New York State Medicaid, alongside agency-model home care, and CDPAP has grown in large part by replacing agency-model care. Only by placing CDPAP in the context of New York’s larger home care program can we understand why it is growing and what, if anything, should be done about it.

Below, we show that since 2018, New York home care utilization has grown at a rate of just 3.9% per year—a significant increase, but hardly a crisis. This overall growth reflects a shift from agency-model home care to CDPAP; agency usage has declined in absolute terms, while CDPAP has grown, resulting in a modest increase in usage overall.

CDPAP and Agency-Model Home Care: A Brief History

In New York (and in many other states), Medicaid beneficiaries may access home care through one of two service models: agency-based and consumer-directed. In the agency model, the beneficiary contracts with a home care agency (in New York a Licensed Home Care Services Agency or LHCSA) which employs a roster of home care workers; the agency hires, trains, and manages the workers, and the beneficiary is assigned a worker at the agency’s discretion. In the consumer-directed model, the beneficiary selects, hires and trains his or her own worker, working with a Fiscal Intermediary (FI) which handles payroll and supports the beneficiary. Beneficiaries in CDPAP often choose to hire friends and family as caregivers. In New York, family members are allowed to work in CDPAP but not in the agency model.[5]

Why do some Medicaid beneficiaries choose CDPAP over agency care? There are a number of advantages to CDPAP: It grants more autonomy and control to the beneficiary, who can choose his or her own caregiver rather than relying on an agency. For people with disabilities who rely on hands-on, intimate care, controlling how and by whom that care is given can be crucial. It also permits beneficiaries to employ a family member, who may already be providing unpaid care, rather than recruiting a stranger. CDPAP also offers somewhat more flexibility than agency-based care in terms of what tasks can be performed by the CDPAP worker.

CDPAP is not a new program in New York; versions of the model have been around since the 1980s, and the Consumer Directed Personal Assistance Association of New York (CDPAANYS) was founded in 2000.[6] However, for many years CDPAP was a very small program, mainly backed by the disability rights community.

CDPAP Has Grown as Agency Home Care Has Decreased

Sometime around 2015, however, that began to change: CDPAP grew dramatically while agency home care began to decline. Research by Step Two Policy Project shows that as recently as 2017, the State spent just $1.3 billion on CDPAP, which represented less than 20% of total New York Medicaid home care spending.[7] Today, CDPAP represents more than half of total home care spending.

To demonstrate this shift, we rely on data provided to the State by managed care organizations participating in New York State’s Partial Capitation Managed Long-Term Care program, the State’s largest long-term care Medicaid program. This data is not comprehensive (other NYS Medicaid programs also provide home care), but we estimate that it covers over 90% of all personal care in New York State. Data were available only for the first half of 2023 and we present annualized figures.

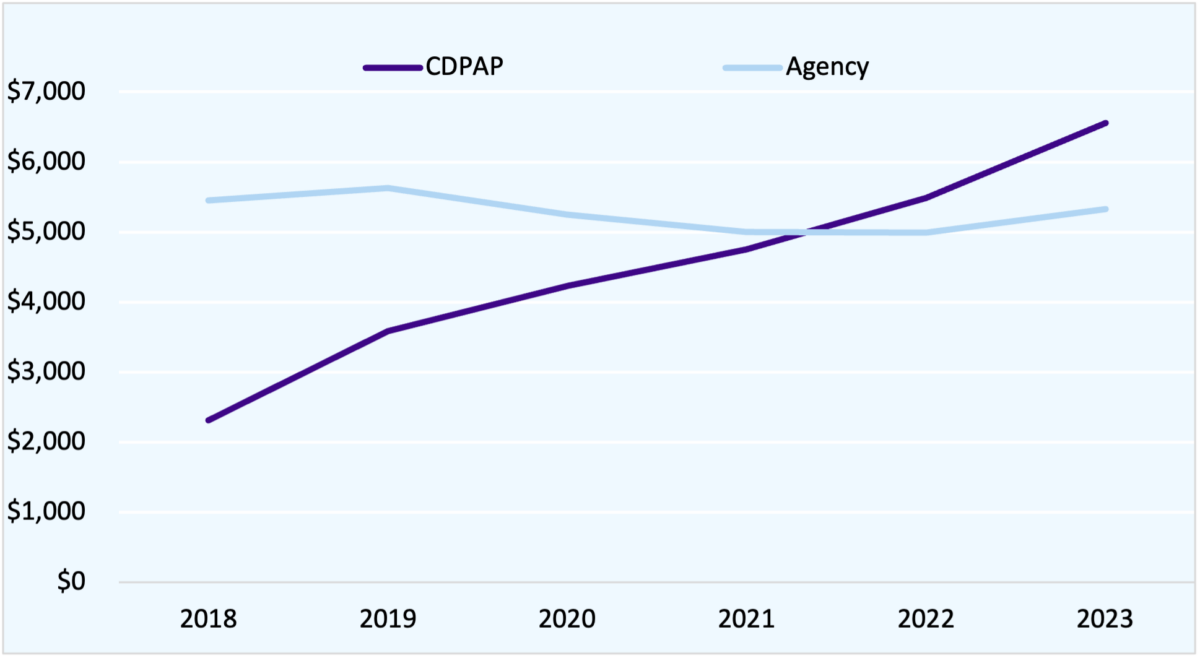

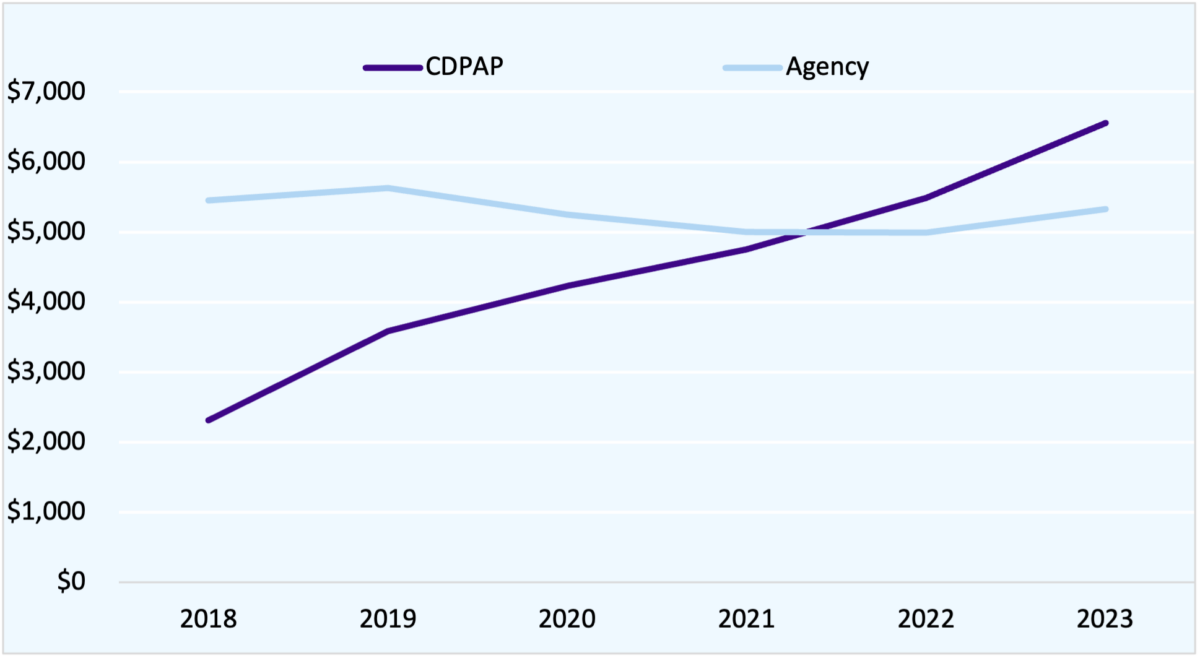

Figure 1. Spending on Home Care by Model, 2018-2023

(Millions of Dollars)

Figure 1 shows that total spending on agency home care has been virtually flat since 2018, even as the state’s population has aged and home care utilization has increased. Total home care spending has grown substantially, from $7.7 billion to $11.9 billion, or around 7% a year, but CDPAP spending has nearly doubled. An analyst studying CDPAP in isolation would see runaway growth—but taking the program as a whole, spending growth is far less dramatic.

It is important to note that this growth in spending is not driven solely by increased utilization. The cost per hour of home care provided has increased substantially since 2018, as the legislature has chosen to require that home care workers be paid more through the Wage Parity program. The average cost to the MCO per hour of home care (which includes wages, payroll expenses, benefits and agency/FI overhead and profit) has risen from $23.09 to $27.91 in the agency model and from $21.89 to $27.38 in CDPAP over the period 2018-2023. Thus, to judge whether utilization is excessive, we must examine not only spending but hours of care provided.

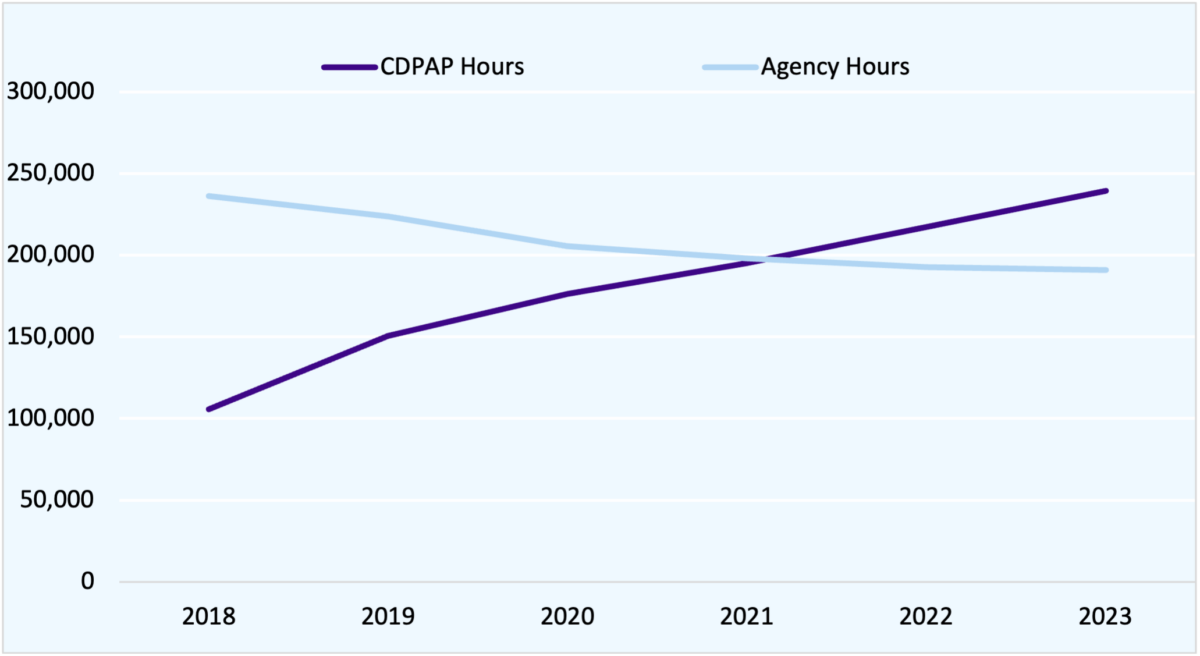

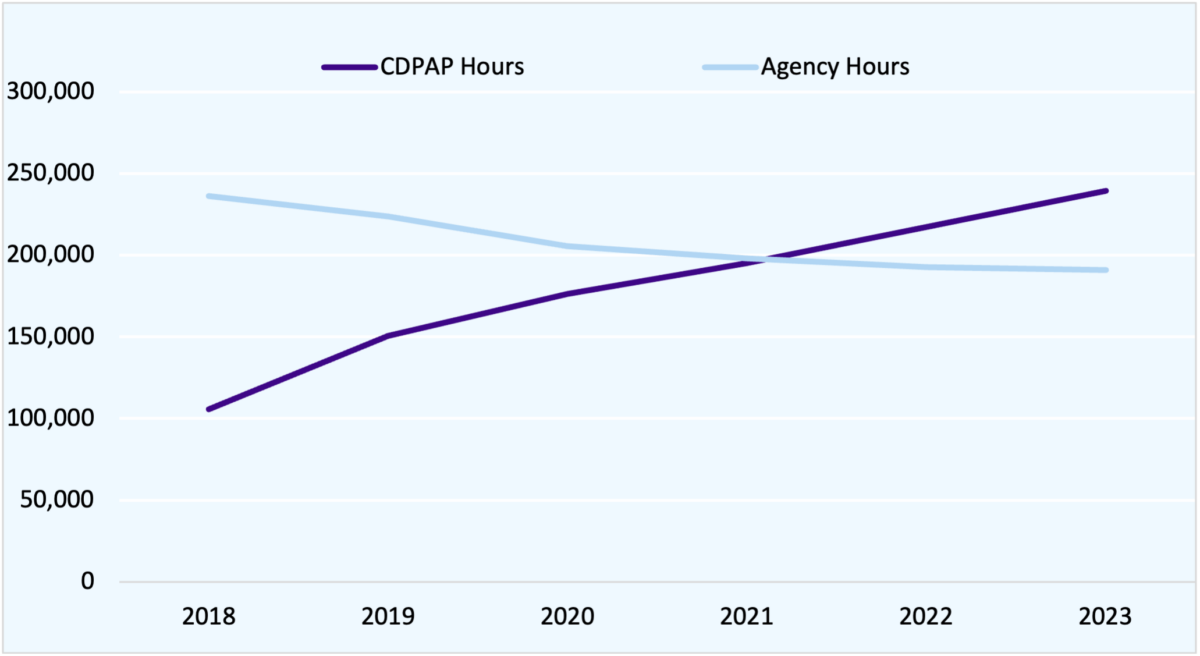

Figure 2. Hours of Home Care by Model, 2018-2023

(Thousands of Hours)

Here the shift is even more striking. Total home care hours increased from 342 million to 431 million—an overall increase of 26 percent over 6 years, or a growth rate of just 3.9 percent per year. CDPAP hours, however, more than doubled, from 106 million to 240 million, while agency hours declined dramatically, from 236 million to 191 million, a 19 percent decrease.

Growth in home care utilization of 26 percent in six years is substantial, but hardly a crisis. Much of this growth is likely accounted for by New York’s aging population; the number of New Yorkers over 65 increased by 14 percent in the same period.

Taking a comprehensive view of New York’s home care program offers a more balanced—and far less alarming—view of New York home care spending than we get if we focus on CDPAP in isolation. The story is clearly not one of runaway home care spending growth overall but of modest, steady growth in overall utilization combined with a major shift from CDPAP to agency home care.

Why Are Consumers Switching to CDPAP?

This shift requires explanation, however. Why have home care users switched to CDPAP? In discussion with experts on the program, I have encountered several theories:

- Consumer awareness and preference. Many people who need home care prefer to direct their own care and/or prefer to be cared for by friends and family. As consumers have become more aware of CDPAP (in part through advertising by fiscal intermediaries), many have chosen to switch.

- Higher cash wages. CDPAP and agency home care are both subject to wage parity requirements, which require agencies and FIs to spend a minimum amount on labor costs. However, home care agencies are more heavily unionized and tend to spend more of this funding on employee healthcare, while many FIs do not offer healthcare and can thus offer higher cash wages. These higher wages may be more attractive to low-income workers and make it easier for beneficiaries to find care under CDPAP.

- Lower cost to MCOs. Under the Managed Long-Term Care program, MLTC managed care organizations receive premiums from the State and use that money to pay for care. Before 2017, CDPAP was substantially cheaper per hour than agency care, since CDPAP was not subject to wage parity. This may have encouraged MCOs to educate beneficiaries about CDPAP. (CDPAP remains somewhat less expensive for MCOs than agency care, but the gap has narrowed dramatically over time.)

- Liberalization of family caregiver rules. Over time, the State has allowed more types of family members to provide care under CDPAP. Most notably, in 2015 the legislature enacted a law allowing the parents of chronically ill or disabled adult children to be paid through CDPAP.[8]

- Workforce shortages, particularly during the pandemic. Home care agencies in many parts of the state have struggled to find staff, with shortages becoming especially acute in 2020-21. Some beneficiaries who could not find care through agencies turned to CDPAP, which allowed them to recruit workers directly, including friends and family members.

Conclusion

Regardless of what is driving the trend, it is clear that CDPAP growth must be seen in the context of New York’s home care program as a whole. Fundamentally, CDPAP and agency home care serve many of the same needs and are substitutes for one another. CDPAP has grown because consumers have preferred it over the agency model. Conversely, efforts to cut or restrict access to CDPAP will likely drive many consumers to seek agency care, negating budgetary savings while putting a severe strain on the home care agency infrastructure. Worse yet, consumers who are not able to find care in the agency model may be at risk of entering a nursing home—which would be far more costly for the State as well as limiting their autonomy. In considering policy changes to New York’s long-term care system, the State must analyze the program as a whole, not isolate a single model.

Sources

[1] https://nypost.com/2024/02/14/us-news/how-nys-6-billion-cdpap-medicaid-program-has-been-abused-overused-for-years/

[2] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-07-22/ny-s-cdpap-home-health-aide-job-program-has-become-a-racket-hochul?embedded-checkout=true

[3] https://www.hklaw.com/en/insights/publications/2024/08/cdpap-legal-storm-continues-new-lawsuit-targets-dohs-rfp

[4] https://www.crainsnewyork.com/health-pulse/kathy-hochul-looks-6b-cdpa-program-her-efforts-cut-medicaid-spending

[5] It should be noted that many state Medicaid programs permit family caregivers to provide paid home care; Washington State and California, for example, allow family caregivers in their consumer-directed models, while Pennsylvania allows family caregivers in both its agency and its consumer-directed model.

[6] https://cdpaanys.org/mission-and-history/

[7] https://www.steptwopolicy.org/post/a-review-of-the-managed-long-term-care-issues-in-the-fy-25-executive-budget

[8] https://matzav.com/124200/

How Fast is New York’s Home Care Program Growing?

December 12, 2024 |

Key Findings

- Much recent reporting has focused on the growth of CDPAP in isolation, but this perspective exaggerates home care growth by ignoring the role of agency-model home care, which accounts for 44 percent of all Medicaid-funded home care in New York.

- CDPAP growth reflects in part the shift of consumers to CDPAP from agency-based home care. Agency-model home care utilization has declined by 19% since 2018.

- Total home care utilization (including both CDPAP and agency models) has increased by just 3.9% per year in the past six years, not much faster than overall growth of the state’s older adult population.

Introduction

The Consumer-Directed Personal Assistance Program (CDPAP) is at the heart of recent debates over Medicaid spending in New York State. Advocates argue that the program, which provides home care for 250,000 Medicaid-enrolled New Yorkers at a cost of roughly $6 billion per year, is critical to the health and independence of elderly and disabled state residents.[1] Critics argue that it’s too expensive and growing too fast, and that it may be subject to abuse. Indeed, Governor Hochul has described the program as “a racket” and proposed massive cuts to the program in her FY 2025 Executive Budget.[2] The legislature rejected most of those cuts, agreeing instead to a major change in how the program works; starting this year, the State will contract with a single fiscal intermediary (FI) to administer the program, replacing hundreds of FIs across the state. However, this change is controversial, and debate over the program will likely continue.[3]

At the heart of this debate is the question of CDPAP growth. New York State Budget Director Blake Washington said during last year’s budget debate that CDPAP has grown more than 1,200 percent over the past decade—a striking figure that has been cited frequently in press coverage of the program.[4] It is certainly true that CDPAP has grown dramatically, but to take this number in isolation is misleading. CDPAP is one of two types of home care offered by New York State Medicaid, alongside agency-model home care, and CDPAP has grown in large part by replacing agency-model care. Only by placing CDPAP in the context of New York’s larger home care program can we understand why it is growing and what, if anything, should be done about it.

Below, we show that since 2018, New York home care utilization has grown at a rate of just 3.9% per year—a significant increase, but hardly a crisis. This overall growth reflects a shift from agency-model home care to CDPAP; agency usage has declined in absolute terms, while CDPAP has grown, resulting in a modest increase in usage overall.

CDPAP and Agency-Model Home Care: A Brief History

In New York (and in many other states), Medicaid beneficiaries may access home care through one of two service models: agency-based and consumer-directed. In the agency model, the beneficiary contracts with a home care agency (in New York a Licensed Home Care Services Agency or LHCSA) which employs a roster of home care workers; the agency hires, trains, and manages the workers, and the beneficiary is assigned a worker at the agency’s discretion. In the consumer-directed model, the beneficiary selects, hires and trains his or her own worker, working with a Fiscal Intermediary (FI) which handles payroll and supports the beneficiary. Beneficiaries in CDPAP often choose to hire friends and family as caregivers. In New York, family members are allowed to work in CDPAP but not in the agency model.[5]

Why do some Medicaid beneficiaries choose CDPAP over agency care? There are a number of advantages to CDPAP: It grants more autonomy and control to the beneficiary, who can choose his or her own caregiver rather than relying on an agency. For people with disabilities who rely on hands-on, intimate care, controlling how and by whom that care is given can be crucial. It also permits beneficiaries to employ a family member, who may already be providing unpaid care, rather than recruiting a stranger. CDPAP also offers somewhat more flexibility than agency-based care in terms of what tasks can be performed by the CDPAP worker.

CDPAP is not a new program in New York; versions of the model have been around since the 1980s, and the Consumer Directed Personal Assistance Association of New York (CDPAANYS) was founded in 2000.[6] However, for many years CDPAP was a very small program, mainly backed by the disability rights community.

CDPAP Has Grown as Agency Home Care Has Decreased

Sometime around 2015, however, that began to change: CDPAP grew dramatically while agency home care began to decline. Research by Step Two Policy Project shows that as recently as 2017, the State spent just $1.3 billion on CDPAP, which represented less than 20% of total New York Medicaid home care spending.[7] Today, CDPAP represents more than half of total home care spending.

To demonstrate this shift, we rely on data provided to the State by managed care organizations participating in New York State’s Partial Capitation Managed Long-Term Care program, the State’s largest long-term care Medicaid program. This data is not comprehensive (other NYS Medicaid programs also provide home care), but we estimate that it covers over 90% of all personal care in New York State. Data were available only for the first half of 2023 and we present annualized figures.

Figure 1. Spending on Home Care by Model, 2018-2023

(Millions of Dollars)

Figure 1 shows that total spending on agency home care has been virtually flat since 2018, even as the state’s population has aged and home care utilization has increased. Total home care spending has grown substantially, from $7.7 billion to $11.9 billion, or around 7% a year, but CDPAP spending has nearly doubled. An analyst studying CDPAP in isolation would see runaway growth—but taking the program as a whole, spending growth is far less dramatic.

It is important to note that this growth in spending is not driven solely by increased utilization. The cost per hour of home care provided has increased substantially since 2018, as the legislature has chosen to require that home care workers be paid more through the Wage Parity program. The average cost to the MCO per hour of home care (which includes wages, payroll expenses, benefits and agency/FI overhead and profit) has risen from $23.09 to $27.91 in the agency model and from $21.89 to $27.38 in CDPAP over the period 2018-2023. Thus, to judge whether utilization is excessive, we must examine not only spending but hours of care provided.

Figure 2. Hours of Home Care by Model, 2018-2023

(Thousands of Hours)

Here the shift is even more striking. Total home care hours increased from 342 million to 431 million—an overall increase of 26 percent over 6 years, or a growth rate of just 3.9 percent per year. CDPAP hours, however, more than doubled, from 106 million to 240 million, while agency hours declined dramatically, from 236 million to 191 million, a 19 percent decrease.

Growth in home care utilization of 26 percent in six years is substantial, but hardly a crisis. Much of this growth is likely accounted for by New York’s aging population; the number of New Yorkers over 65 increased by 14 percent in the same period.

Taking a comprehensive view of New York’s home care program offers a more balanced—and far less alarming—view of New York home care spending than we get if we focus on CDPAP in isolation. The story is clearly not one of runaway home care spending growth overall but of modest, steady growth in overall utilization combined with a major shift from CDPAP to agency home care.

Why Are Consumers Switching to CDPAP?

This shift requires explanation, however. Why have home care users switched to CDPAP? In discussion with experts on the program, I have encountered several theories:

- Consumer awareness and preference. Many people who need home care prefer to direct their own care and/or prefer to be cared for by friends and family. As consumers have become more aware of CDPAP (in part through advertising by fiscal intermediaries), many have chosen to switch.

- Higher cash wages. CDPAP and agency home care are both subject to wage parity requirements, which require agencies and FIs to spend a minimum amount on labor costs. However, home care agencies are more heavily unionized and tend to spend more of this funding on employee healthcare, while many FIs do not offer healthcare and can thus offer higher cash wages. These higher wages may be more attractive to low-income workers and make it easier for beneficiaries to find care under CDPAP.

- Lower cost to MCOs. Under the Managed Long-Term Care program, MLTC managed care organizations receive premiums from the State and use that money to pay for care. Before 2017, CDPAP was substantially cheaper per hour than agency care, since CDPAP was not subject to wage parity. This may have encouraged MCOs to educate beneficiaries about CDPAP. (CDPAP remains somewhat less expensive for MCOs than agency care, but the gap has narrowed dramatically over time.)

- Liberalization of family caregiver rules. Over time, the State has allowed more types of family members to provide care under CDPAP. Most notably, in 2015 the legislature enacted a law allowing the parents of chronically ill or disabled adult children to be paid through CDPAP.[8]

- Workforce shortages, particularly during the pandemic. Home care agencies in many parts of the state have struggled to find staff, with shortages becoming especially acute in 2020-21. Some beneficiaries who could not find care through agencies turned to CDPAP, which allowed them to recruit workers directly, including friends and family members.

Conclusion

Regardless of what is driving the trend, it is clear that CDPAP growth must be seen in the context of New York’s home care program as a whole. Fundamentally, CDPAP and agency home care serve many of the same needs and are substitutes for one another. CDPAP has grown because consumers have preferred it over the agency model. Conversely, efforts to cut or restrict access to CDPAP will likely drive many consumers to seek agency care, negating budgetary savings while putting a severe strain on the home care agency infrastructure. Worse yet, consumers who are not able to find care in the agency model may be at risk of entering a nursing home—which would be far more costly for the State as well as limiting their autonomy. In considering policy changes to New York’s long-term care system, the State must analyze the program as a whole, not isolate a single model.

Sources

[1] https://nypost.com/2024/02/14/us-news/how-nys-6-billion-cdpap-medicaid-program-has-been-abused-overused-for-years/

[2] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-07-22/ny-s-cdpap-home-health-aide-job-program-has-become-a-racket-hochul?embedded-checkout=true

[3] https://www.hklaw.com/en/insights/publications/2024/08/cdpap-legal-storm-continues-new-lawsuit-targets-dohs-rfp

[4] https://www.crainsnewyork.com/health-pulse/kathy-hochul-looks-6b-cdpa-program-her-efforts-cut-medicaid-spending

[5] It should be noted that many state Medicaid programs permit family caregivers to provide paid home care; Washington State and California, for example, allow family caregivers in their consumer-directed models, while Pennsylvania allows family caregivers in both its agency and its consumer-directed model.

[6] https://cdpaanys.org/mission-and-history/

[7] https://www.steptwopolicy.org/post/a-review-of-the-managed-long-term-care-issues-in-the-fy-25-executive-budget

[8] https://matzav.com/124200/