Budget Alert: New York State’s 2003-2004 Budget Outlook

October 19, 2002 |

October 19, 2002. By Frank Mauro.

Late last month while discussing a broad range of topics with the editorial board of The (Troy) Record, Senate Majority Leader Joseph Bruno predicted that New York State faces a budget gap of $8 billion to $10 billion in its 2003-2004 budget. The magnitude of this prediction is obvious when one focuses on the fact that the state’s tax supported General Fund budget is about $40 billion. Thus, if Senator Bruno’s prediction is accurate, the steps necessary to balance next year’s budget will have an extremely negative effect on the state’s economy and quality of life. This situation will only be slightly less problematical if the Fiscal Policy Institute’s estimate of a $5 to $7 billion gap is more accurate.

The problems that the state faces in 2002-2003 are compounded by the possibility that the state budget for the current 2002-2003 state fiscal year may end up in the red. The NYC-based Citizens Budget Commission recently offered the opinion that the current year budget would be out of balance by about $1.2 billion. And State Comptroller and Democratic gubernatorial candidate Carl McCall, in issuing the Cash Basis Financial Statements for the first six months (April 1 through September 30) of the current fiscal year, offered a similarly pessimistic outlook for the current year. Governor Pataki’s Budget Director, Carole E. Stone, issued a stern rebuke of the Comptroller’s report, claiming that the “report issued yesterday by the State Comptroller regarding the State’s mid-year finances contained misleading and inaccurate information regarding the State’s revenues and finances.”

According to Stone, “overall spending is on plan” since All Funds spending in the first six months of the fiscal year ($42.7 billion) was 48 percent of the total amount of All Funds spending ($89.6 billion) planned for in the 2002-2003 Enacted Budget. She stated that the state’s financial plan “calls for very modest growth in revenue and reasonable reductions in spending” over the balance of the current fiscal year and that “according to the Comptroller’s figures, we are doing slightly better than the plan.”

Given the multitude of inter-fund transfers that are embedded in the state’s financial operations, it is impossible for anyone to determine from the state’s interim financial exactly what is going on. Whether New York faces a gap for the current fiscal year, however, the outlook is not good for next year.

It seems like Deja Vu all over again.

In fact, the state’s current fiscal situation is very reminiscient of the period in New York State’s recent history that gave rise to the creation of the Fiscal Policy Institute.

The Fiscal Policy Institute (FPI) was an outgrowth of a broad based Coalition for Economic Priorities that was formed in 1989, at the beginning of New York State’s last fiscal crisis.

In its second year of operations, this coalition succeeded in getting the Governor and the Legislature to delay the remaining steps of the overly generous 1987 personal income tax cuts.

The state’s 1990-1991 budget was precariously balanced through spending cuts and revenue increases but shortly after that November’s election (when Governor Cuomo was elected to his third term) Governor Cuomo called a special session of the legislature to make more cuts. And by early December 1990, the Legislature had enacted a mid-year $1 billion budget balancing package. That Deficit Reduction Plan, as it was called, contained no tax increases. This is an important point to keep in mind in the current budget balancing debate so that we do not repeat the mistakes of the past. While New York deferred some tax cuts during the early 1990s, the amount of real tax increasaes enacted during that period paled in comparison to the amount of budget balancing that was done through cuts in state services and aid to localities. In fact, to balance its own budget, the State Government cut State Revenue Sharing with counties, towns, cities and villages by more than 50%, from over $1 billion a year to less than $500 million. This forced local governments to cut services and increase regressive property and sales taxes.

2002 is also a gubernatorial election year and the recently adopted budget for 2002-2003 is using billions of dollars of reserves and one-shots to get past November 5th with as little pain as possible – very limited tax increases and only modest budget cuts.

Why does NYS have a budget gap?

Governor Pataki says we have a budget gap primarily because of the World Trade Center disaster. And, in a sense he is right. State tax revenues are down by billions because of (a) the direct impact of the disaster (the loss of thousands of lives and the destruction of 26 million square feet of prime office space) and (b) the indirect impact on numerous industries – from hotels to apparel manufacturing.

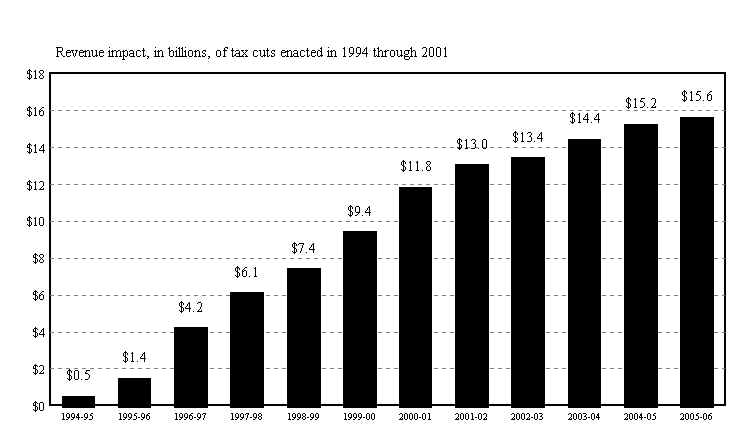

But in another sense, we have a budget gap because of the overly generous tax cuts of recent years. The tax cuts enacted in 1994 through 2000 are reducing tax revenues this year by over $12 billion. Over the last several years, FPI and others warned that the magnitude of these tax cuts was such that they could not be sustained through even a slight downturn in the economy without forcing the kind of deep budget cuts that the Governor said would not be necessary when he pushed these tax cuts through the Legislature. (Not that he faced very much opposition during a period when it appeared that the boom on Wall Street would never end and that we could have massive tax cuts and still maintain vital services.) The chickens have now clearly come hoom to roost.

The tax cuts enacted since 1994 will reduce state revenues by more than $16 billion per year when fully implemented. And, as Governor Pataki likes to say, this will mean a cumulative reduction of $100 billion in state tax reveues over this multi-year period – the largest tax reduction program ever implemented by any state in the history of our country. What the Governor fails to acknowledge is that if we had enacted tax cuts of two-thirds or even less of this amount, it would have still have been the largest state tax reduction program in American history BUT we would not have been so ill-prepared for the current downturn.

Figure 1. Impact of Yax Cuts by State Fiscal Year

Figure 2. The resources generated by the 1990s boom have been used primarily for tax cuts.

How big is the state budget gap?

In October 2001, the NYS Budget Director said that the WTC disaster could reduce state revenues by $3 billion in 2001-2002 and $6 billion for 2002-2003. Three months later, in the Executive Budget, Governor Pataki estimated the budget gap at $1.1 billion for 2001-2002 (all attributable to the decline in tax revenues as a result of 9/11) and $5.7 billion for 2002-2003 ($4 billion due to 9/11 and $1.7 billion attributable to the state’s “structural” deficit). The Senate and the Assembly initially estimated a smaller gap than the Governor but they changed their minds as actual ciollections during the first four months of 2002 came in well below their expectations. It now looks like the 2002-2003 revenue shortfall gap may be as big as the budget director projected last fall.

The 2003-2004 budget gap will be at least $5 billion because of the way the 2002-2003 budget gap was closed and because the economy and Wall Street have continued to flounder. Even if there is a strong turnaround on Wall Street during late 2002, it will take a year or so before that upturn is reflected in state revenue growth.

$1 billion in reserves were used to close the year-end gap in the 2001-2002 fiscal year. In the 2002-2003 Executive Budget, the Governor proposed to close this year’s budget gap by using up most of the remaining cash reserves that the state had built up over the last several years. Among the $3.3 billion in nonrecurring resources that the Governor proposed to use in balancing the 2002-2003 budget were the following:

- Fiscal Responsibility Reserve – $1.5 Billion

- TANF (Welfare Reform) Surplus – $885 million

- Refund Reserve Account – $547 million

- Public Authority Balances – $200 million

- Environmental Protection Fund – $120 million

- Various Other Reserves – $415 million

In adopting the 2002-2003 budget, the legislature used an additional $1 billion or so in one-shots in order to avoid many of the Governor’s proposed service cuts. There are also other risks in the state’s financial plans. For example, the Governor’s January 2002 Health Care Bill counts on a substantial increase in federal aid (through an increase in the share of Medicaid costs picked up by the federal government) beginning October 1, 2002. Before breaking for its August recess, the U. S. Senate by a large bipartisan majority adopted such a State Fiscal Relief measure on a temporary 18-month basis. This plan adopted by the Senate would provide over $7 billion in fiscal relief to the states to assist them during the current recession, with over $1 billion of that amount going to New York State, but the President and the U. S. House of Representatives have not yet gotten on board.

Even if the economy had recovered more quickly than it has, revenues would not have grow sufficiently to cover the costs that are being covered this year by reserves that won’t be available next year. For example, the Governor’s January 2002 projections for 2003-2004 counted on strong revenue growth (over 5.25%) but still projected a gap of $2.8 billion. Given the fact that the Legislature used an additional $1+ billion to fund its restorations and additions to the Governor’s budget and the fact that the economy is recovering more slowly than hoped for in the Executive Budget, it appears that the gap for next year will be at least $5 billion.

Can’t we continue to use the TANF surplus money to balance the state budget?

In order to close the budget gap for 2002-2003, New York State exhausted the TANF surplus taht it had accumulated over the first five years of the TANF program. In fact, if recession worsens NYS face caseload increases. In such an event, it may have to go even further and cut back on its use of TANF block grant funds to finance other important programs such as protective and preventive child welfare services.

Figure 3: New York’s TANF fund balances in Washington are shrinking and will be almost exhausted by the end of the next fiscal year.

Isn’t the recession over?

Earlier in the year, most economists thought the national recession was over. But there is now talk of the possibility of a so-called “double dip” recession like the U. S. experienced in the early 1980s.

For the New York budget, however, we could still have problems whether or not the national recession is over. This is because recessions do not affect all parts of the country equally. For example, New York, New England and California did much better than the rest of the nation during the recession of the early 1980s, and much worse during the recession of the early 1990s. During the current recession New York was doing better than the nation as a whole until September 11th. But since the attacks, our economy has suffered greatly. New York City which had led the state’s boom during the late 1990s has lost over 117,000 jobs since September 11th, and the losses are growing. The NYS Assembly Ways and Means Committee recently issued a report based on unpublished data that indicates that those losses might really be over 200,000 but that they will not be reflected in the Labor Department’s published data until the annual revisions of that data is published in February or March of 2003.

The changes withing New York State are also uneven – and in a direction that bodes ill for state revenues. During the boom of the 1990s, New York City was the engine of the state’s growth and the source of the huge increases that the state enjoyed in personal income tax receipts. Even though New York had cut its personal income tax rates, personal income tax receipts grew from 50% of all state tax revenues to 60% because of the unprecedented growth in capital gains income, Wall Street bonuses, and stock options. But unfortuantely New York City has gone from boomtown to slowdown.

Figure 4: Trends in New York State Employment by Region

In September 2002, the Rockefeller Institute of Government, in its quarterly State Revenue Report, reported that state tax revenues nationwide, in the April-June 2002 quarter, had declined by 10.4 percent compared to the year before. This is the worst quarter of decline since the Institute began to track state tax revenues over eleven years ago. In New York, revenues were down 19.4% – only three states (MA, CA, OR) experienced greater revenue losses. Overall, state tax revenues have now declined for four straight quarters. This is worrisome not only because of the persistent weakness, but also because the decline seems to be accelerating.

New York Needs to Balance Its Budget in an Economically Sensible Manner

I. NYS needs to press the case for federal reimbursement of tax revenue losses directly attributable to the international attacks of September 11th. Governor Pataki raised this issue (asking for $12 billion of such help) in his October 2001 request for $54 billion in federal help, but since then the emphasis has shifted to federal money for other purposes. U. S. Representative Carolyn Maloney (D-Manhattan) has commissioned GAO and Congressional Research Service studies that have made the case economically and legally for such aid. She was recently joined by New York’s U.S. Senators, Hillary Clinton and Charles Schumer, and other members of the Congressional delegation in calling for the changes needed in federal law to protect not only New York but also any other areas of the country that might ever fall victim to such a destructive international attacks such aid. While several members of Congress from other parts of the country have joined in cosponsoring Rep. Maloney’s legislation on this subject, more bridge building and education is necessary. Business, labor, professional, civic and other organizations in New York State can contribute to this effort by working with their counterparts throughout the country and with their national organizations in Washington, DC and elsewhere.

II. At the state level, the Governor and the Legislature need to balance state budget in a balanced and economically sensible manner. As Joseph Stiglitz, winner of the 2001 Nobel Prize in Economics, and Peter Orszag of the Brookings Institution have explained in Budget Cuts vs. Tax Increases at the State Level: Is One More Counter-Productive than the Other During a Recession?, cuts in spending in the local economy have a much more negative effect during an economic downturn than certain kinds of tax increases. According to Stiglitz and Orszag, macroeconomic theory tells us that in a recession both tax increases and spending cuts are harmful to the economy – because they reduce aggregate demand. The adverse impact of a tax increase, however, is smaller than the adverse impact of a spending reduction because some of the tax increase would result in reduced saving rather than reduced consumption. Some types of spending reductions, like reductions in the purchasing of goods and services in the local economy, reduce consumption on a dollar for dollar basis and are the most harmful of all budget balancing actions. And some tax increases are more harmful to the economy than others. Their conclusion is that “tax increases on higher income households are the least damaging mechanism for closing state fiscal deficits in the short run. Reductions in government spending on goods and services, or reductions in transfer payments to lower-income families, are likely to be more damaging to the economy than tax increases focused on higher-income households.”

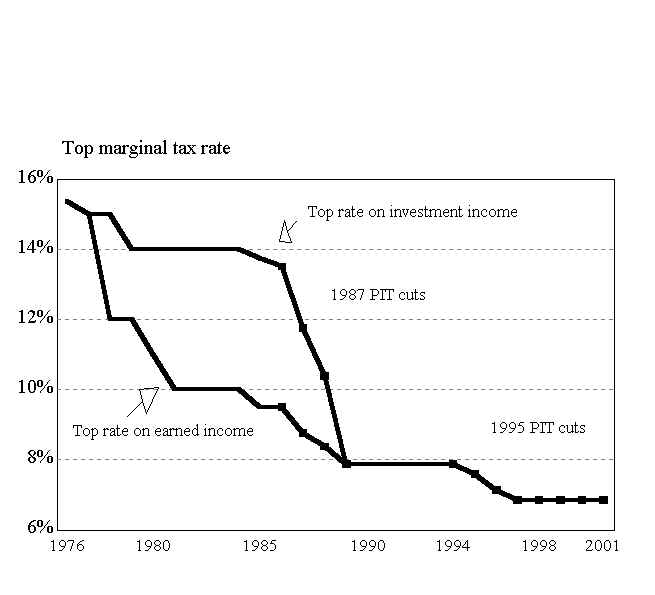

A. Some progressivity must be returned to the State’s Personal Income Tax. New York State has cut its top personal income tax rate by more than 50% over the last 25 years. New York used to have 3rd highest top income tax rate of all the 42 states with income taxes. It is now 19th out of 42 with a top rate of 6.85%. In September 2001, for example, North Carolina raised its top rate from 7.75% to 8.25% for 3 years (2001 through 2003). This year, Massachusetts postponed scheduled income tax cuts and raised its tax on income from capital gains.

A 7/10ths of 1% surcharge on portion of income over $100,000, and another 7/10ths of 1% on portion over $200,000 would raise $2.7 billion to $3 billion per year. This would make New York State’s top PIT rate the same as North Carolina’s.

B. New York State must also reform and modernize its approach to taxing multistate and multinational corporations. Corporations that tap New York markets should carry a fair share of the bill for the services that allow them to operate profitably in our state. Earlier this year New Jersey enacted legislation closing $1B in corporate loopholes such as the royalty scams used by Toys R’ Us and Sherwin-Williams to avoid taxation in New York State. In addition, the Corporate Alternate Minimum Tax should be restored to its previous levels to provide a floor under the state’s corporate income tax.

Budget Alert: New York State’s 2003-2004 Budget Outlook

October 19, 2002 |

October 19, 2002. By Frank Mauro.

Late last month while discussing a broad range of topics with the editorial board of The (Troy) Record, Senate Majority Leader Joseph Bruno predicted that New York State faces a budget gap of $8 billion to $10 billion in its 2003-2004 budget. The magnitude of this prediction is obvious when one focuses on the fact that the state’s tax supported General Fund budget is about $40 billion. Thus, if Senator Bruno’s prediction is accurate, the steps necessary to balance next year’s budget will have an extremely negative effect on the state’s economy and quality of life. This situation will only be slightly less problematical if the Fiscal Policy Institute’s estimate of a $5 to $7 billion gap is more accurate.

The problems that the state faces in 2002-2003 are compounded by the possibility that the state budget for the current 2002-2003 state fiscal year may end up in the red. The NYC-based Citizens Budget Commission recently offered the opinion that the current year budget would be out of balance by about $1.2 billion. And State Comptroller and Democratic gubernatorial candidate Carl McCall, in issuing the Cash Basis Financial Statements for the first six months (April 1 through September 30) of the current fiscal year, offered a similarly pessimistic outlook for the current year. Governor Pataki’s Budget Director, Carole E. Stone, issued a stern rebuke of the Comptroller’s report, claiming that the “report issued yesterday by the State Comptroller regarding the State’s mid-year finances contained misleading and inaccurate information regarding the State’s revenues and finances.”

According to Stone, “overall spending is on plan” since All Funds spending in the first six months of the fiscal year ($42.7 billion) was 48 percent of the total amount of All Funds spending ($89.6 billion) planned for in the 2002-2003 Enacted Budget. She stated that the state’s financial plan “calls for very modest growth in revenue and reasonable reductions in spending” over the balance of the current fiscal year and that “according to the Comptroller’s figures, we are doing slightly better than the plan.”

Given the multitude of inter-fund transfers that are embedded in the state’s financial operations, it is impossible for anyone to determine from the state’s interim financial exactly what is going on. Whether New York faces a gap for the current fiscal year, however, the outlook is not good for next year.

It seems like Deja Vu all over again.

In fact, the state’s current fiscal situation is very reminiscient of the period in New York State’s recent history that gave rise to the creation of the Fiscal Policy Institute.

The Fiscal Policy Institute (FPI) was an outgrowth of a broad based Coalition for Economic Priorities that was formed in 1989, at the beginning of New York State’s last fiscal crisis.

In its second year of operations, this coalition succeeded in getting the Governor and the Legislature to delay the remaining steps of the overly generous 1987 personal income tax cuts.

The state’s 1990-1991 budget was precariously balanced through spending cuts and revenue increases but shortly after that November’s election (when Governor Cuomo was elected to his third term) Governor Cuomo called a special session of the legislature to make more cuts. And by early December 1990, the Legislature had enacted a mid-year $1 billion budget balancing package. That Deficit Reduction Plan, as it was called, contained no tax increases. This is an important point to keep in mind in the current budget balancing debate so that we do not repeat the mistakes of the past. While New York deferred some tax cuts during the early 1990s, the amount of real tax increasaes enacted during that period paled in comparison to the amount of budget balancing that was done through cuts in state services and aid to localities. In fact, to balance its own budget, the State Government cut State Revenue Sharing with counties, towns, cities and villages by more than 50%, from over $1 billion a year to less than $500 million. This forced local governments to cut services and increase regressive property and sales taxes.

2002 is also a gubernatorial election year and the recently adopted budget for 2002-2003 is using billions of dollars of reserves and one-shots to get past November 5th with as little pain as possible – very limited tax increases and only modest budget cuts.

Why does NYS have a budget gap?

Governor Pataki says we have a budget gap primarily because of the World Trade Center disaster. And, in a sense he is right. State tax revenues are down by billions because of (a) the direct impact of the disaster (the loss of thousands of lives and the destruction of 26 million square feet of prime office space) and (b) the indirect impact on numerous industries – from hotels to apparel manufacturing.

But in another sense, we have a budget gap because of the overly generous tax cuts of recent years. The tax cuts enacted in 1994 through 2000 are reducing tax revenues this year by over $12 billion. Over the last several years, FPI and others warned that the magnitude of these tax cuts was such that they could not be sustained through even a slight downturn in the economy without forcing the kind of deep budget cuts that the Governor said would not be necessary when he pushed these tax cuts through the Legislature. (Not that he faced very much opposition during a period when it appeared that the boom on Wall Street would never end and that we could have massive tax cuts and still maintain vital services.) The chickens have now clearly come hoom to roost.

The tax cuts enacted since 1994 will reduce state revenues by more than $16 billion per year when fully implemented. And, as Governor Pataki likes to say, this will mean a cumulative reduction of $100 billion in state tax reveues over this multi-year period – the largest tax reduction program ever implemented by any state in the history of our country. What the Governor fails to acknowledge is that if we had enacted tax cuts of two-thirds or even less of this amount, it would have still have been the largest state tax reduction program in American history BUT we would not have been so ill-prepared for the current downturn.

Figure 1. Impact of Yax Cuts by State Fiscal Year

Figure 2. The resources generated by the 1990s boom have been used primarily for tax cuts.

How big is the state budget gap?

In October 2001, the NYS Budget Director said that the WTC disaster could reduce state revenues by $3 billion in 2001-2002 and $6 billion for 2002-2003. Three months later, in the Executive Budget, Governor Pataki estimated the budget gap at $1.1 billion for 2001-2002 (all attributable to the decline in tax revenues as a result of 9/11) and $5.7 billion for 2002-2003 ($4 billion due to 9/11 and $1.7 billion attributable to the state’s “structural” deficit). The Senate and the Assembly initially estimated a smaller gap than the Governor but they changed their minds as actual ciollections during the first four months of 2002 came in well below their expectations. It now looks like the 2002-2003 revenue shortfall gap may be as big as the budget director projected last fall.

The 2003-2004 budget gap will be at least $5 billion because of the way the 2002-2003 budget gap was closed and because the economy and Wall Street have continued to flounder. Even if there is a strong turnaround on Wall Street during late 2002, it will take a year or so before that upturn is reflected in state revenue growth.

$1 billion in reserves were used to close the year-end gap in the 2001-2002 fiscal year. In the 2002-2003 Executive Budget, the Governor proposed to close this year’s budget gap by using up most of the remaining cash reserves that the state had built up over the last several years. Among the $3.3 billion in nonrecurring resources that the Governor proposed to use in balancing the 2002-2003 budget were the following:

- Fiscal Responsibility Reserve – $1.5 Billion

- TANF (Welfare Reform) Surplus – $885 million

- Refund Reserve Account – $547 million

- Public Authority Balances – $200 million

- Environmental Protection Fund – $120 million

- Various Other Reserves – $415 million

In adopting the 2002-2003 budget, the legislature used an additional $1 billion or so in one-shots in order to avoid many of the Governor’s proposed service cuts. There are also other risks in the state’s financial plans. For example, the Governor’s January 2002 Health Care Bill counts on a substantial increase in federal aid (through an increase in the share of Medicaid costs picked up by the federal government) beginning October 1, 2002. Before breaking for its August recess, the U. S. Senate by a large bipartisan majority adopted such a State Fiscal Relief measure on a temporary 18-month basis. This plan adopted by the Senate would provide over $7 billion in fiscal relief to the states to assist them during the current recession, with over $1 billion of that amount going to New York State, but the President and the U. S. House of Representatives have not yet gotten on board.

Even if the economy had recovered more quickly than it has, revenues would not have grow sufficiently to cover the costs that are being covered this year by reserves that won’t be available next year. For example, the Governor’s January 2002 projections for 2003-2004 counted on strong revenue growth (over 5.25%) but still projected a gap of $2.8 billion. Given the fact that the Legislature used an additional $1+ billion to fund its restorations and additions to the Governor’s budget and the fact that the economy is recovering more slowly than hoped for in the Executive Budget, it appears that the gap for next year will be at least $5 billion.

Can’t we continue to use the TANF surplus money to balance the state budget?

In order to close the budget gap for 2002-2003, New York State exhausted the TANF surplus taht it had accumulated over the first five years of the TANF program. In fact, if recession worsens NYS face caseload increases. In such an event, it may have to go even further and cut back on its use of TANF block grant funds to finance other important programs such as protective and preventive child welfare services.

Figure 3: New York’s TANF fund balances in Washington are shrinking and will be almost exhausted by the end of the next fiscal year.

Isn’t the recession over?

Earlier in the year, most economists thought the national recession was over. But there is now talk of the possibility of a so-called “double dip” recession like the U. S. experienced in the early 1980s.

For the New York budget, however, we could still have problems whether or not the national recession is over. This is because recessions do not affect all parts of the country equally. For example, New York, New England and California did much better than the rest of the nation during the recession of the early 1980s, and much worse during the recession of the early 1990s. During the current recession New York was doing better than the nation as a whole until September 11th. But since the attacks, our economy has suffered greatly. New York City which had led the state’s boom during the late 1990s has lost over 117,000 jobs since September 11th, and the losses are growing. The NYS Assembly Ways and Means Committee recently issued a report based on unpublished data that indicates that those losses might really be over 200,000 but that they will not be reflected in the Labor Department’s published data until the annual revisions of that data is published in February or March of 2003.

The changes withing New York State are also uneven – and in a direction that bodes ill for state revenues. During the boom of the 1990s, New York City was the engine of the state’s growth and the source of the huge increases that the state enjoyed in personal income tax receipts. Even though New York had cut its personal income tax rates, personal income tax receipts grew from 50% of all state tax revenues to 60% because of the unprecedented growth in capital gains income, Wall Street bonuses, and stock options. But unfortuantely New York City has gone from boomtown to slowdown.

Figure 4: Trends in New York State Employment by Region

In September 2002, the Rockefeller Institute of Government, in its quarterly State Revenue Report, reported that state tax revenues nationwide, in the April-June 2002 quarter, had declined by 10.4 percent compared to the year before. This is the worst quarter of decline since the Institute began to track state tax revenues over eleven years ago. In New York, revenues were down 19.4% – only three states (MA, CA, OR) experienced greater revenue losses. Overall, state tax revenues have now declined for four straight quarters. This is worrisome not only because of the persistent weakness, but also because the decline seems to be accelerating.

New York Needs to Balance Its Budget in an Economically Sensible Manner

I. NYS needs to press the case for federal reimbursement of tax revenue losses directly attributable to the international attacks of September 11th. Governor Pataki raised this issue (asking for $12 billion of such help) in his October 2001 request for $54 billion in federal help, but since then the emphasis has shifted to federal money for other purposes. U. S. Representative Carolyn Maloney (D-Manhattan) has commissioned GAO and Congressional Research Service studies that have made the case economically and legally for such aid. She was recently joined by New York’s U.S. Senators, Hillary Clinton and Charles Schumer, and other members of the Congressional delegation in calling for the changes needed in federal law to protect not only New York but also any other areas of the country that might ever fall victim to such a destructive international attacks such aid. While several members of Congress from other parts of the country have joined in cosponsoring Rep. Maloney’s legislation on this subject, more bridge building and education is necessary. Business, labor, professional, civic and other organizations in New York State can contribute to this effort by working with their counterparts throughout the country and with their national organizations in Washington, DC and elsewhere.

II. At the state level, the Governor and the Legislature need to balance state budget in a balanced and economically sensible manner. As Joseph Stiglitz, winner of the 2001 Nobel Prize in Economics, and Peter Orszag of the Brookings Institution have explained in Budget Cuts vs. Tax Increases at the State Level: Is One More Counter-Productive than the Other During a Recession?, cuts in spending in the local economy have a much more negative effect during an economic downturn than certain kinds of tax increases. According to Stiglitz and Orszag, macroeconomic theory tells us that in a recession both tax increases and spending cuts are harmful to the economy – because they reduce aggregate demand. The adverse impact of a tax increase, however, is smaller than the adverse impact of a spending reduction because some of the tax increase would result in reduced saving rather than reduced consumption. Some types of spending reductions, like reductions in the purchasing of goods and services in the local economy, reduce consumption on a dollar for dollar basis and are the most harmful of all budget balancing actions. And some tax increases are more harmful to the economy than others. Their conclusion is that “tax increases on higher income households are the least damaging mechanism for closing state fiscal deficits in the short run. Reductions in government spending on goods and services, or reductions in transfer payments to lower-income families, are likely to be more damaging to the economy than tax increases focused on higher-income households.”

A. Some progressivity must be returned to the State’s Personal Income Tax. New York State has cut its top personal income tax rate by more than 50% over the last 25 years. New York used to have 3rd highest top income tax rate of all the 42 states with income taxes. It is now 19th out of 42 with a top rate of 6.85%. In September 2001, for example, North Carolina raised its top rate from 7.75% to 8.25% for 3 years (2001 through 2003). This year, Massachusetts postponed scheduled income tax cuts and raised its tax on income from capital gains.

A 7/10ths of 1% surcharge on portion of income over $100,000, and another 7/10ths of 1% on portion over $200,000 would raise $2.7 billion to $3 billion per year. This would make New York State’s top PIT rate the same as North Carolina’s.

B. New York State must also reform and modernize its approach to taxing multistate and multinational corporations. Corporations that tap New York markets should carry a fair share of the bill for the services that allow them to operate profitably in our state. Earlier this year New Jersey enacted legislation closing $1B in corporate loopholes such as the royalty scams used by Toys R’ Us and Sherwin-Williams to avoid taxation in New York State. In addition, the Corporate Alternate Minimum Tax should be restored to its previous levels to provide a floor under the state’s corporate income tax.