Making Sense of New York’s Medicaid Long-Term Care Spending

December 4, 2024 |

Medicaid long-term care costs are a hot-button issue in New York. Elder advocates, the disability rights community, and unions frequently call for the State to spend more on long-term care as its population ages, while critics argue that current spending levels are unsustainable and that the State must scale back. Resolving this debate requires putting New York’s long-term care spending in national context. This blog post shows that New York does indeed spend more on Medicaid long-term care than most states, and that this higher spending is driven primarily by higher enrollment, particularly among seniors, rather than by higher per-enrollee spending. This high enrollment reflects policymakers’ decision to make long-term care, particularly home care, relatively accessible for working- and middle-class seniors. [1]

Medicaid: A Tale of Two Programs

Medicaid is usually understood as a source of health insurance for low-income working-age adults and children, just as Medicare provides health insurance for seniors. Medicaid does indeed play this role, providing insurance for 4.5 million individuals through the Mainstream Managed Care program[2] and another 571,000 through Child Health Plus[3], among other programs. but it also plays a different role: It funds long-term care for elderly and disabled Americans.

Medicaid must play this crucial role for a simple reason: Medicare does not cover most long-term care services, such as home care and nursing home care, and these services can be extremely expensive. Nursing home care, for example, can cost nearly $160,000 per year in New York,[4] and private-pay home care costs can easily exceed $100,000. Thus many elderly and disabled Americans—even those with substantial income or savings—will ultimately need to rely on Medicaid for their long-term care needs.

Understanding this aspect of Medicaid is crucial for the simple reason that long-term care spending represents a huge chunk of the Medicaid budget, both in New York and nationally. Elderly and disabled New Yorkers made up just 20.7 percent of enrollees in New York in federal FY 2021, but they accounted for 59 percent of Medicaid spending on benefits. (Nationally, elderly and disabled Medicaid beneficiaries represent 21.1 percent of all beneficiaries and account for 52.3 percent of spending.) Not all spending on elderly and disabled beneficiaries goes to long-term care, but most does. In federal FY 2020, 43 percent of New York’s Medicaid budget went to long-term care.[5]

Because long-term care spending is such a large share of total Medicaid spending, and because the beneficiary and service mix of LTSS Medicaid is so different from that of the rest of the program, it is often useful to think of Medicaid as two separate programs: One that provides comprehensive health insurance to able-bodied adults and children, and one that provides long-term care benefits to elderly and disabled beneficiaries, most of whom receive health insurance through Medicare.

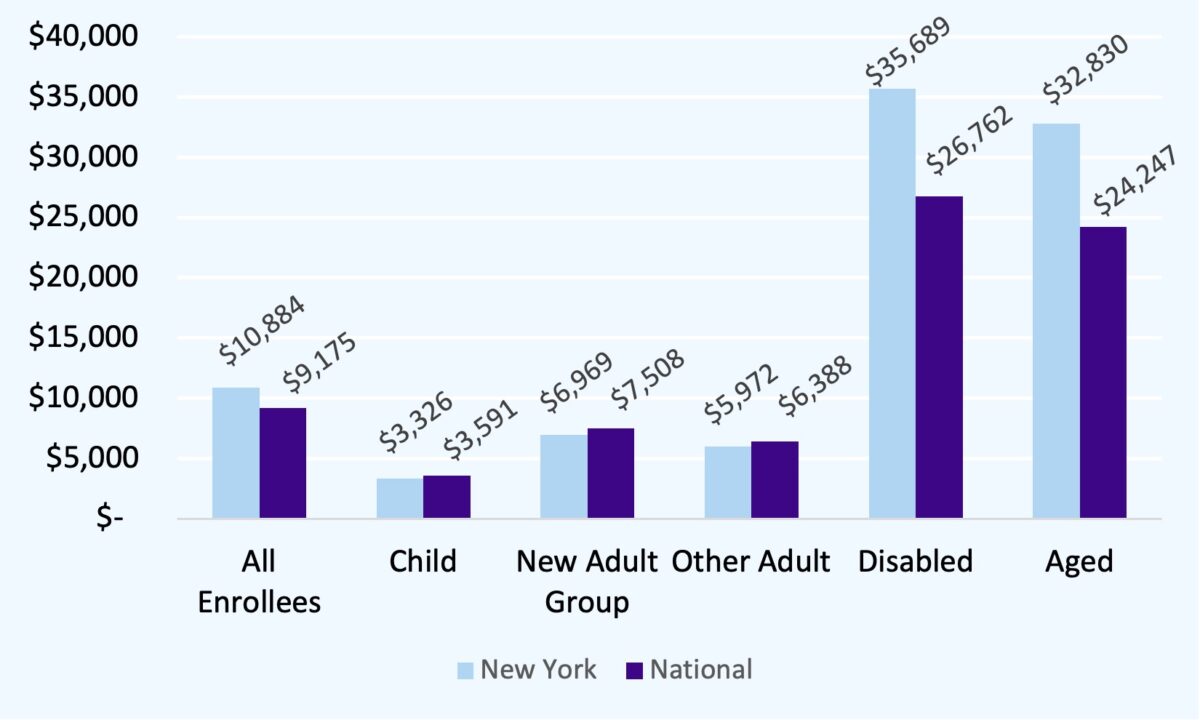

How does Medicaid spending in New York stack up across these categories? In federal FY 2021, New York spent an average of $10,884 per Medicaid beneficiary per year.[6] To put that number in context, the average annual cost of a private employer-sponsored individual health plan in New York in 2021 was $8,542.[7] But average Medicaid spending varied dramatically by beneficiary category: New York spent just $6,969 per beneficiary for adults in the ACA expansion population, $5,972 per beneficiary for adults in traditional Medicaid, and $3,326 per beneficiary for children. New York’s spending for these service categories was lower than the national average and dramatically lower than the per-beneficiary cost of private health insurance.

Figure 1. Medicaid Benefit Spending per Eligible Enrollee, Federal FY 2021

Source: MACStats Databook 2023. Figures given are for full-year equivalent full-benefit enrollees

Spending per beneficiary on full-benefit dual-eligible enrollees is significantly higher, both in New York and nationally. In 2021, New York spent $32,830 per enrollee on its aged population (compared to a national average of $24,247), and $35,689 on its disabled enrollees (compared to a national figure of $26,762).

Since most elderly and disabled Medicaid beneficiaries are “dual-eligible” and receive basic health insurance through Medicare, the vast majority of Medicaid spending on these beneficiaries goes to services that aren’t covered by Medicare. The vast majority of this spending goes to long-term supports and services (LTSS), either in “institutional” settings like nursing homes or in home- and community-based services like home care.

It may seem surprising that per-beneficiary spending is so high in this service category, both in New York and nationally, particularly given that Medicare is picking up the tab for the bulk of healthcare spending in this group. But it is important to note that most dual-eligible beneficiaries become eligible for full Medicaid benefits only because they need long-term care. Most non-disabled working-age Medicaid beneficiaries will not need to be hospitalized in any given year, but most elderly and disabled beneficiaries will use long-term care—otherwise they wouldn’t be on Medicaid.

Sidebar: What is long-term care, and why does Medicaid cover it?

Long-term care is assistance with “activities of daily living” (ADLs), such as eating, bathing and toileting. This care was traditionally provided primarily in nursing homes, but a large and growing share of it is now provided at home or in community-based settings (HCBS). HCBS can include a variety of services, like social adult day care, but the largest HCBS category is “home care,” in which a paid caregiver comes to the beneficiary’s home to assist with activities. Medicaid beneficiaries’ need for long-term care varies widely, of course—some beneficiaries may be largely self-sufficient and require just a few hours a week of home care, while others may require round-the-clock care.

This care is typically not “medical” in nature and so was excluded from Medicare when it was enacted in 1965. However, care for the indigent elderly and disabled was traditionally the concern of state governments, and this spending was eligible for federal Medicaid matching funds, so state Medicaid programs took up the challenge of paying for long-term care.

Initially, Medicaid would pay for long-term care only if it was provided in institutional settings like nursing homes. Over time, state policymakers across the country came to see home care as a more desirable and more cost-effective alternative to nursing home care. Today all states, including New York, offer a home care benefit under Medicaid, although states vary widely in the extent of their home care offerings.

Thus, 9.5 million Americans, including over 900,000 New Yorkers, are enrolled in both Medicare and Medicaid: Medicare covers their healthcare costs, including hospital care, physician visits, and medications, while Medicaid pays for long-term care.

New York’s Medicaid Long-Term Care Spending in National Context

Many commentators have described New York’s Medicaid long-term care spending as excessive and unsustainable. Does New York spend more on Medicaid LTSS than other states? If so, what drives this spending?

On a per-enrollee basis, New York’s LTSS spending is higher than the national average, but by no means an outlier. New York’s per-enrollee spending on elderly dual-eligible enrollees ranks 13th in the nation, behind that of states like North Dakota, Oregon, New Hampshire and Connecticut, and its per-enrollee spending on disabled enrollees ranks eighth in the nation, behind that of states like Connecticut, Minnesota, Washington and Virginia.[8]

However, New York’s LTSS Medicaid spending per state resident tells a different story: New York spent $1520.59 per state resident on long-term care, much higher than the national average and second-highest in the country after the District of Columbia.[9] HCBS is the driver of New York’s spending: 71.2 percent of this spending went to home- and community-based services such as home care, with the remainder funding institutional care.

Thus, New York’s spending on LTSS per enrollee is broadly in line with that of peer states, but its overall spending is significantly higher. What explains this divergence? The answer is simple: Higher enrollment, and specifically higher enrollment among seniors. Nationally, roughly 10.5 percent of Americans aged 65 and older are “full-benefit” (LTSS-eligible) Medicaid enrollees; New York, however, has nearly double as many enrollees, at 19.2 percent—second only to the District of Columbia (22.6 percent) and California (21.4 percent). These three jurisdictions stand apart in enrolling seniors in Medicaid; the next-highest-enrollment state, Massachusetts, enrolls just 14.8 percent of seniors, and most states enroll fewer than 10 percent of seniors.

With nearly twice as many seniors accessing services as the national average, it is little wonder that New York’s Medicaid program spends more on long-term care than do those of other states. To understand why so many more seniors in New York are able to access Medicaid, we must explore the issue of Medicaid eligibility for elderly and disabled individuals who require long-term care.

New York’s Long-Term Care System: Prioritizing Access

Who is eligible for long-term care under Medicaid? To understand the dynamics of Medicaid eligibility it is important to note that many people become eligible for Medicaid after they begin to need long-term care, even if they start out comfortably middle-class. A senior who retires at 65 with significant assets and income but begins to need long-term care after a few years may quickly find that paying out-of-pocket for long-term care consumes all his or her savings and renders him or her eligible for Medicaid. State Medicaid rules determine at what point and under what circumstances such an individual is poor enough to qualify for Medicaid.

These rules are complex and vary widely by state. For non-elderly, non-disabled individuals Medicaid eligibility is typically determined through a simple income test, but dual-eligible elderly and disabled beneficiaries face a more involved process. Typically, determining eligibility will involve:

- An income test, which varies by state but is often more stringent than the income test for non-dual enrollees. However, states may allow individuals to “spend down” to meet the income test if their income is below the limit after they have paid their medical and long-term care bills.

- An asset test, in which enrollees are excluded if they have the financial resources to pay for care out of pocket. In many states the asset test may exclude some forms of property, such as a primary residence or personal vehicle.

- An asset “look-back” period: To prevent potential enrollees from giving away assets to family members or putting them in trust to get around the asset test, the vast majority of states disqualify individuals for Medicaid if they have given away assets during a fixed period of time prior to their application known as a “look-back” period. The typical look-back period is five years.

- Rules governing Medicaid planning and trusts: Some states allow beneficiaries to maintain income or assets through trust structures, such as Medicaid Asset Protection Trusts (used to meet the asset test) and pooled income trusts (used to meet the income test), but states vary widely in their rules about who can use these structures and in what circumstances.

- Functionality-based tests: All states require prospective enrollees to have a demonstrated need for long-term care, but exactly how disabled an individual must be to qualify varies widely.

- Caps and rationing for HCBS: Many states limit the total number of enrollees who can receive HCBS at any given time, so even qualifying individuals may be placed on a wait list. In 2023, 38 states had an HCBS wait list.[10]

Thus, in a state with restrictive eligibility rules, an individual may need to spend her entire life savings paying out-of-pocket for long-term care before becoming eligible for Medicaid, and even then she may find herself wait-listed for HCBS and be forced into a nursing home. In a state with more generous rules, that same individual may become eligible much sooner, may be able to retain some savings and protect some income through Medicaid trust structures, and may immediately qualify for HCBS when she does become eligible. Both individuals may ultimately become eligible for Medicaid, but the second will spend more time in the program than the first.

New York has been a national leader in expanding access to Medicaid long-term care, particularly HCBS, and this policy choice largely explains New York’s higher Medicaid enrollment among seniors. For example, in New York, dual-eligibles benefit from:

- A relatively high asset limit of $30,000, compared to $2,000 in the majority of states.

- No asset look-back for HCBS, allowing applicants to transfer assets or protect them in a trust immediately before seeking access to Medicaid long-term care. (The State has chosen to impose a 30-month look-back period beginning in 2025, but even this restriction is more generous than the 60-month look-back imposed in most states.)[11] Only New York and California offer access to HCBS with no asset look-back.

- Relatively liberal rules allowing dual-eligibles to retain some income above the $1,732 monthly income threshold through pooled income trusts.

- A right to HCBS with no cap on enrollment and no wait list.

These policy choices explain why many more seniors in New York access LTSS through Medicaid than in most other states—which in turn largely explains New York’s relatively high Medicaid spending.

Protecting New York’s Long-Term Care System

Medicaid long-term care spending has become a key site of concern for New York policymakers. In her fiscal year 2024 budget briefing book, Governor Hochul described this growth as unsustainable,[12] and the State has moved to restrict access to Medicaid long-term care by imposing an asset look-back and requiring that individuals meet a higher functional threshold to qualify for HCBS. With the State facing potential cuts in federal Medicaid funding under a Trump administration, policymakers may be tempted to consider further cuts.

This would be a move in the wrong direction. Access to long-term care is a right, and it makes little sense for the State to force seniors and people with disabilities to impoverish themselves in order to access it. Restricting access to Medicaid HCBS will place a substantial burden on working families, who will need to pay for care out of pocket, and on family caregivers who may be forced to leave the workforce to provide unpaid care if Medicaid doesn’t fill the gap. Instead, New York should protect its nation-leading long-term care system and follow the lead of Vice President Kamala Harris, who during her presidential campaign proposed making access to long-term care a universal entitlement.[13]

That’s not to say we shouldn’t be concerned about rising Medicaid costs. The State should explore ways to make Medicaid dollars go farther, for instance by eliminating the wasteful managed long-term care (MLTC) program, and we will explore that topic in a future post. Savings from reform should be reinvested in ensuring continued access to long-term care for New York families.

[1] A note on the data: Comparing Medicaid programs across states is challenging, since each state administers its own program and data, and service definitions are not necessarily comparable across programs. This difficulty has been accentuated by the growth of Medicaid managed care: Many states with managed care systems, including New York, report only state payments to managed care plans and do not break down spending by service. The key source for cross-state comparison is the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC) annual data book, MACStats, which analyzes data reported by states to the federal government through Form CMS-64. Unfortunately, there is a significant lag in this data: The most recent (2023) edition of MACStats analyzes data only through federal fiscal year 2021 or, for some measures, 2022. A further limitation of this data is that the CMS-64 form does not break down spending by service category for managed care systems, making it impossible to compare, for example, home care spending in states like New York that use managed long-term care. Service-level spending is available through the Transformed Medical Information System (T-MSIS) data and through surveys of states, but the data lag here is even greater: The most recent CMS report on LTSS spending using this data, published in June 2023, covers federal FY 2020 (available at https://www.mathematica.org/publications/medicaid-long-term-services-and-supports-annual-expenditures-report-federal-fiscal-year-2020). This is why cross-state comparison data cited below largely dates from federal FYs 2020 and 2021. While LTSS spending in New York and nationally has certainly grown since 2020, we believe that the overall trends described below have continued.

[2] October Managed Care Enrollment Report, https://www.health.ny.gov/health_care/managed_care/reports/enrollment/monthly/2024/docs/en10_24.pdf

[3] October Child Health Plus Enrollment Report, https://www.health.ny.gov/statistics/child_health_plus/enrollment/docs/2024-10.pdf

[4] American Council on Aging, “2021 Nursing Home Costs by State and Region,” https://www.medicaidplanningassistance.org/nursing-home-costs/

[5] Medicaid LTSS Annual Expenditures Report: Federal Fiscal Year 2020, Figure III.2.

[6] Figures cited are for “full-benefit” Medicaid enrollees. Full-benefit enrollees receive either comprehensive health coverage or long-term care coverage through Medicaid; “partial-benefit” enrollees are those for whom Medicaid pays only Medicare premiums and copays.

[7] https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/single-coverage/?currentTimeframe=2&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D

[8] Spending figures given for full-benefit enrollees. MACStats Databook 2023, Exhibit 22.

[9] CMS LTSS Spending Report

[10] https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/a-look-at-waiting-lists-for-medicaid-home-and-community-based-services-from-2016-to-2023/

[11] https://www.medicaidplanningassistance.org/medicaid-eligibility-new-york/

[12] https://www.budget.ny.gov/pubs/archive/fy25/ex/book/briefingbook.pdf#page=18

[13] https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/vice-president-harris-proposal-to-broaden-medicare-coverage-of-home-care/

Making Sense of New York’s Medicaid Long-Term Care Spending

December 4, 2024 |

Medicaid long-term care costs are a hot-button issue in New York. Elder advocates, the disability rights community, and unions frequently call for the State to spend more on long-term care as its population ages, while critics argue that current spending levels are unsustainable and that the State must scale back. Resolving this debate requires putting New York’s long-term care spending in national context. This blog post shows that New York does indeed spend more on Medicaid long-term care than most states, and that this higher spending is driven primarily by higher enrollment, particularly among seniors, rather than by higher per-enrollee spending. This high enrollment reflects policymakers’ decision to make long-term care, particularly home care, relatively accessible for working- and middle-class seniors. [1]

Medicaid: A Tale of Two Programs

Medicaid is usually understood as a source of health insurance for low-income working-age adults and children, just as Medicare provides health insurance for seniors. Medicaid does indeed play this role, providing insurance for 4.5 million individuals through the Mainstream Managed Care program[2] and another 571,000 through Child Health Plus[3], among other programs. but it also plays a different role: It funds long-term care for elderly and disabled Americans.

Medicaid must play this crucial role for a simple reason: Medicare does not cover most long-term care services, such as home care and nursing home care, and these services can be extremely expensive. Nursing home care, for example, can cost nearly $160,000 per year in New York,[4] and private-pay home care costs can easily exceed $100,000. Thus many elderly and disabled Americans—even those with substantial income or savings—will ultimately need to rely on Medicaid for their long-term care needs.

Understanding this aspect of Medicaid is crucial for the simple reason that long-term care spending represents a huge chunk of the Medicaid budget, both in New York and nationally. Elderly and disabled New Yorkers made up just 20.7 percent of enrollees in New York in federal FY 2021, but they accounted for 59 percent of Medicaid spending on benefits. (Nationally, elderly and disabled Medicaid beneficiaries represent 21.1 percent of all beneficiaries and account for 52.3 percent of spending.) Not all spending on elderly and disabled beneficiaries goes to long-term care, but most does. In federal FY 2020, 43 percent of New York’s Medicaid budget went to long-term care.[5]

Because long-term care spending is such a large share of total Medicaid spending, and because the beneficiary and service mix of LTSS Medicaid is so different from that of the rest of the program, it is often useful to think of Medicaid as two separate programs: One that provides comprehensive health insurance to able-bodied adults and children, and one that provides long-term care benefits to elderly and disabled beneficiaries, most of whom receive health insurance through Medicare.

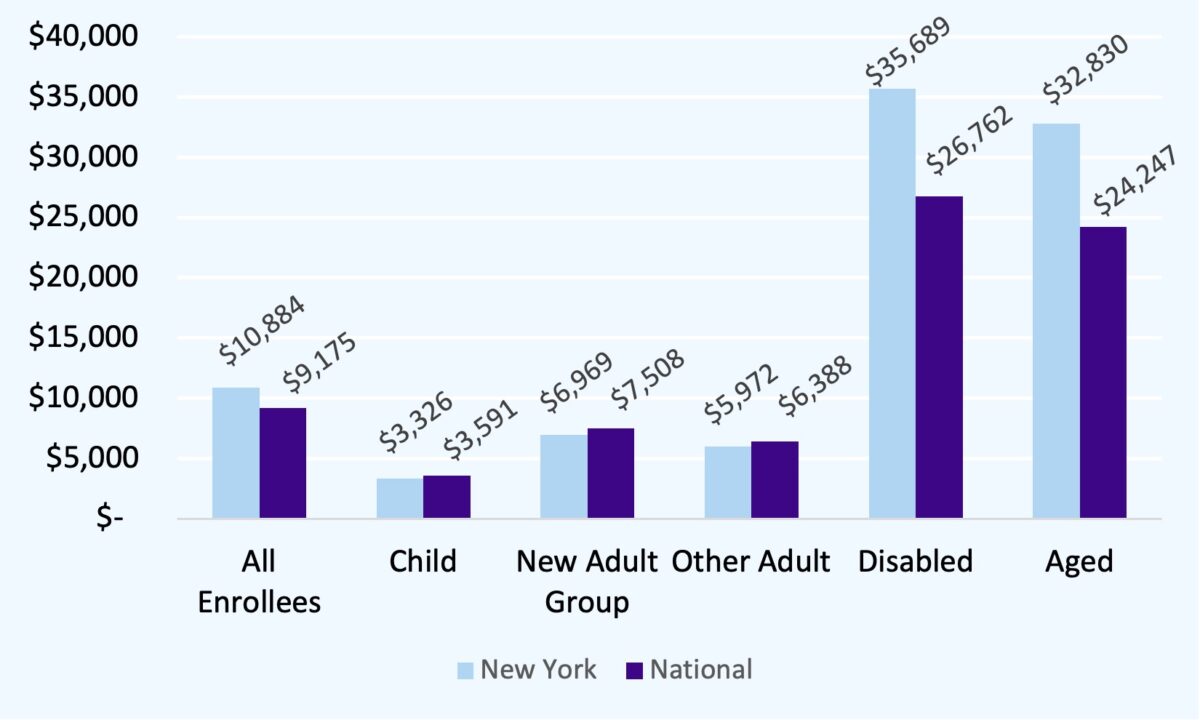

How does Medicaid spending in New York stack up across these categories? In federal FY 2021, New York spent an average of $10,884 per Medicaid beneficiary per year.[6] To put that number in context, the average annual cost of a private employer-sponsored individual health plan in New York in 2021 was $8,542.[7] But average Medicaid spending varied dramatically by beneficiary category: New York spent just $6,969 per beneficiary for adults in the ACA expansion population, $5,972 per beneficiary for adults in traditional Medicaid, and $3,326 per beneficiary for children. New York’s spending for these service categories was lower than the national average and dramatically lower than the per-beneficiary cost of private health insurance.

Figure 1. Medicaid Benefit Spending per Eligible Enrollee, Federal FY 2021

Source: MACStats Databook 2023. Figures given are for full-year equivalent full-benefit enrollees

Spending per beneficiary on full-benefit dual-eligible enrollees is significantly higher, both in New York and nationally. In 2021, New York spent $32,830 per enrollee on its aged population (compared to a national average of $24,247), and $35,689 on its disabled enrollees (compared to a national figure of $26,762).

Since most elderly and disabled Medicaid beneficiaries are “dual-eligible” and receive basic health insurance through Medicare, the vast majority of Medicaid spending on these beneficiaries goes to services that aren’t covered by Medicare. The vast majority of this spending goes to long-term supports and services (LTSS), either in “institutional” settings like nursing homes or in home- and community-based services like home care.

It may seem surprising that per-beneficiary spending is so high in this service category, both in New York and nationally, particularly given that Medicare is picking up the tab for the bulk of healthcare spending in this group. But it is important to note that most dual-eligible beneficiaries become eligible for full Medicaid benefits only because they need long-term care. Most non-disabled working-age Medicaid beneficiaries will not need to be hospitalized in any given year, but most elderly and disabled beneficiaries will use long-term care—otherwise they wouldn’t be on Medicaid.

Sidebar: What is long-term care, and why does Medicaid cover it?

Long-term care is assistance with “activities of daily living” (ADLs), such as eating, bathing and toileting. This care was traditionally provided primarily in nursing homes, but a large and growing share of it is now provided at home or in community-based settings (HCBS). HCBS can include a variety of services, like social adult day care, but the largest HCBS category is “home care,” in which a paid caregiver comes to the beneficiary’s home to assist with activities. Medicaid beneficiaries’ need for long-term care varies widely, of course—some beneficiaries may be largely self-sufficient and require just a few hours a week of home care, while others may require round-the-clock care.

This care is typically not “medical” in nature and so was excluded from Medicare when it was enacted in 1965. However, care for the indigent elderly and disabled was traditionally the concern of state governments, and this spending was eligible for federal Medicaid matching funds, so state Medicaid programs took up the challenge of paying for long-term care.

Initially, Medicaid would pay for long-term care only if it was provided in institutional settings like nursing homes. Over time, state policymakers across the country came to see home care as a more desirable and more cost-effective alternative to nursing home care. Today all states, including New York, offer a home care benefit under Medicaid, although states vary widely in the extent of their home care offerings.

Thus, 9.5 million Americans, including over 900,000 New Yorkers, are enrolled in both Medicare and Medicaid: Medicare covers their healthcare costs, including hospital care, physician visits, and medications, while Medicaid pays for long-term care.

New York’s Medicaid Long-Term Care Spending in National Context

Many commentators have described New York’s Medicaid long-term care spending as excessive and unsustainable. Does New York spend more on Medicaid LTSS than other states? If so, what drives this spending?

On a per-enrollee basis, New York’s LTSS spending is higher than the national average, but by no means an outlier. New York’s per-enrollee spending on elderly dual-eligible enrollees ranks 13th in the nation, behind that of states like North Dakota, Oregon, New Hampshire and Connecticut, and its per-enrollee spending on disabled enrollees ranks eighth in the nation, behind that of states like Connecticut, Minnesota, Washington and Virginia.[8]

However, New York’s LTSS Medicaid spending per state resident tells a different story: New York spent $1520.59 per state resident on long-term care, much higher than the national average and second-highest in the country after the District of Columbia.[9] HCBS is the driver of New York’s spending: 71.2 percent of this spending went to home- and community-based services such as home care, with the remainder funding institutional care.

Thus, New York’s spending on LTSS per enrollee is broadly in line with that of peer states, but its overall spending is significantly higher. What explains this divergence? The answer is simple: Higher enrollment, and specifically higher enrollment among seniors. Nationally, roughly 10.5 percent of Americans aged 65 and older are “full-benefit” (LTSS-eligible) Medicaid enrollees; New York, however, has nearly double as many enrollees, at 19.2 percent—second only to the District of Columbia (22.6 percent) and California (21.4 percent). These three jurisdictions stand apart in enrolling seniors in Medicaid; the next-highest-enrollment state, Massachusetts, enrolls just 14.8 percent of seniors, and most states enroll fewer than 10 percent of seniors.

With nearly twice as many seniors accessing services as the national average, it is little wonder that New York’s Medicaid program spends more on long-term care than do those of other states. To understand why so many more seniors in New York are able to access Medicaid, we must explore the issue of Medicaid eligibility for elderly and disabled individuals who require long-term care.

New York’s Long-Term Care System: Prioritizing Access

Who is eligible for long-term care under Medicaid? To understand the dynamics of Medicaid eligibility it is important to note that many people become eligible for Medicaid after they begin to need long-term care, even if they start out comfortably middle-class. A senior who retires at 65 with significant assets and income but begins to need long-term care after a few years may quickly find that paying out-of-pocket for long-term care consumes all his or her savings and renders him or her eligible for Medicaid. State Medicaid rules determine at what point and under what circumstances such an individual is poor enough to qualify for Medicaid.

These rules are complex and vary widely by state. For non-elderly, non-disabled individuals Medicaid eligibility is typically determined through a simple income test, but dual-eligible elderly and disabled beneficiaries face a more involved process. Typically, determining eligibility will involve:

- An income test, which varies by state but is often more stringent than the income test for non-dual enrollees. However, states may allow individuals to “spend down” to meet the income test if their income is below the limit after they have paid their medical and long-term care bills.

- An asset test, in which enrollees are excluded if they have the financial resources to pay for care out of pocket. In many states the asset test may exclude some forms of property, such as a primary residence or personal vehicle.

- An asset “look-back” period: To prevent potential enrollees from giving away assets to family members or putting them in trust to get around the asset test, the vast majority of states disqualify individuals for Medicaid if they have given away assets during a fixed period of time prior to their application known as a “look-back” period. The typical look-back period is five years.

- Rules governing Medicaid planning and trusts: Some states allow beneficiaries to maintain income or assets through trust structures, such as Medicaid Asset Protection Trusts (used to meet the asset test) and pooled income trusts (used to meet the income test), but states vary widely in their rules about who can use these structures and in what circumstances.

- Functionality-based tests: All states require prospective enrollees to have a demonstrated need for long-term care, but exactly how disabled an individual must be to qualify varies widely.

- Caps and rationing for HCBS: Many states limit the total number of enrollees who can receive HCBS at any given time, so even qualifying individuals may be placed on a wait list. In 2023, 38 states had an HCBS wait list.[10]

Thus, in a state with restrictive eligibility rules, an individual may need to spend her entire life savings paying out-of-pocket for long-term care before becoming eligible for Medicaid, and even then she may find herself wait-listed for HCBS and be forced into a nursing home. In a state with more generous rules, that same individual may become eligible much sooner, may be able to retain some savings and protect some income through Medicaid trust structures, and may immediately qualify for HCBS when she does become eligible. Both individuals may ultimately become eligible for Medicaid, but the second will spend more time in the program than the first.

New York has been a national leader in expanding access to Medicaid long-term care, particularly HCBS, and this policy choice largely explains New York’s higher Medicaid enrollment among seniors. For example, in New York, dual-eligibles benefit from:

- A relatively high asset limit of $30,000, compared to $2,000 in the majority of states.

- No asset look-back for HCBS, allowing applicants to transfer assets or protect them in a trust immediately before seeking access to Medicaid long-term care. (The State has chosen to impose a 30-month look-back period beginning in 2025, but even this restriction is more generous than the 60-month look-back imposed in most states.)[11] Only New York and California offer access to HCBS with no asset look-back.

- Relatively liberal rules allowing dual-eligibles to retain some income above the $1,732 monthly income threshold through pooled income trusts.

- A right to HCBS with no cap on enrollment and no wait list.

These policy choices explain why many more seniors in New York access LTSS through Medicaid than in most other states—which in turn largely explains New York’s relatively high Medicaid spending.

Protecting New York’s Long-Term Care System

Medicaid long-term care spending has become a key site of concern for New York policymakers. In her fiscal year 2024 budget briefing book, Governor Hochul described this growth as unsustainable,[12] and the State has moved to restrict access to Medicaid long-term care by imposing an asset look-back and requiring that individuals meet a higher functional threshold to qualify for HCBS. With the State facing potential cuts in federal Medicaid funding under a Trump administration, policymakers may be tempted to consider further cuts.

This would be a move in the wrong direction. Access to long-term care is a right, and it makes little sense for the State to force seniors and people with disabilities to impoverish themselves in order to access it. Restricting access to Medicaid HCBS will place a substantial burden on working families, who will need to pay for care out of pocket, and on family caregivers who may be forced to leave the workforce to provide unpaid care if Medicaid doesn’t fill the gap. Instead, New York should protect its nation-leading long-term care system and follow the lead of Vice President Kamala Harris, who during her presidential campaign proposed making access to long-term care a universal entitlement.[13]

That’s not to say we shouldn’t be concerned about rising Medicaid costs. The State should explore ways to make Medicaid dollars go farther, for instance by eliminating the wasteful managed long-term care (MLTC) program, and we will explore that topic in a future post. Savings from reform should be reinvested in ensuring continued access to long-term care for New York families.

[1] A note on the data: Comparing Medicaid programs across states is challenging, since each state administers its own program and data, and service definitions are not necessarily comparable across programs. This difficulty has been accentuated by the growth of Medicaid managed care: Many states with managed care systems, including New York, report only state payments to managed care plans and do not break down spending by service. The key source for cross-state comparison is the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC) annual data book, MACStats, which analyzes data reported by states to the federal government through Form CMS-64. Unfortunately, there is a significant lag in this data: The most recent (2023) edition of MACStats analyzes data only through federal fiscal year 2021 or, for some measures, 2022. A further limitation of this data is that the CMS-64 form does not break down spending by service category for managed care systems, making it impossible to compare, for example, home care spending in states like New York that use managed long-term care. Service-level spending is available through the Transformed Medical Information System (T-MSIS) data and through surveys of states, but the data lag here is even greater: The most recent CMS report on LTSS spending using this data, published in June 2023, covers federal FY 2020 (available at https://www.mathematica.org/publications/medicaid-long-term-services-and-supports-annual-expenditures-report-federal-fiscal-year-2020). This is why cross-state comparison data cited below largely dates from federal FYs 2020 and 2021. While LTSS spending in New York and nationally has certainly grown since 2020, we believe that the overall trends described below have continued.

[2] October Managed Care Enrollment Report, https://www.health.ny.gov/health_care/managed_care/reports/enrollment/monthly/2024/docs/en10_24.pdf

[3] October Child Health Plus Enrollment Report, https://www.health.ny.gov/statistics/child_health_plus/enrollment/docs/2024-10.pdf

[4] American Council on Aging, “2021 Nursing Home Costs by State and Region,” https://www.medicaidplanningassistance.org/nursing-home-costs/

[5] Medicaid LTSS Annual Expenditures Report: Federal Fiscal Year 2020, Figure III.2.

[6] Figures cited are for “full-benefit” Medicaid enrollees. Full-benefit enrollees receive either comprehensive health coverage or long-term care coverage through Medicaid; “partial-benefit” enrollees are those for whom Medicaid pays only Medicare premiums and copays.

[7] https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/single-coverage/?currentTimeframe=2&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D

[8] Spending figures given for full-benefit enrollees. MACStats Databook 2023, Exhibit 22.

[9] CMS LTSS Spending Report

[10] https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/a-look-at-waiting-lists-for-medicaid-home-and-community-based-services-from-2016-to-2023/

[11] https://www.medicaidplanningassistance.org/medicaid-eligibility-new-york/

[12] https://www.budget.ny.gov/pubs/archive/fy25/ex/book/briefingbook.pdf#page=18

[13] https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/vice-president-harris-proposal-to-broaden-medicare-coverage-of-home-care/