Congestion Pricing “vs.” Millionaire’s Tax: Why Not Do Both?

October 30, 2017 |

October 30, 2017.

Here’s a story you don’t hear every day: in the latest spat between Governor Andrew Cuomo and New York City Mayor De Blasio, both of them are right. Congestion pricing, the governor’s proposal, and a surcharge to the millionaire’s tax, the mayor’s proposal, are both good ideas.

The not-so-secret feuding between the governor and the mayor has not served New Yorkers well. From the serious to the petty, the two Democrats don’t seem to be able to get along about much. But, in their dueling proposals to provide much-needed funding to improve New York City’s transit system, they should get over their differences and say yes to both ideas.

The Mayor’s proposal is straightforward: increase the income tax on people who can most easily bear it, and who benefit from the city’s having a functioning public transit system whether or not they use it themselves. The governor called the mayor’s proposal “dead on arrival.” Well, the proposal would be looking a whole lot healthier if the state’s highest official were giving it a boost rather than trashing the idea.

The mayor’s proposal would generate revenue for transit upgrades, and also for “fair fares,” half-price subway entrance for low-income New Yorkers.

Meantime, Governor Cuomo has suggested revisiting the idea of congestion pricing on the bridges and tunnels coming into Manhattan, but the mayor says he does not believe in congestion pricing. That’s too bad. Congestion pricing is a good idea whose time has come. The governor hasn’t put out a specific proposal yet, but the general idea is to put a higher price on coming through the city’s bridges and tunnels at peak hours, and a lower price in off-peak times.

By giving drivers an incentive to use the crossings before or after rush hour, the bridges and tunnels would be used more efficiently and with less extreme backups at the entrances. And, of course, the funds raised would support the public transportation that would give at least some drivers a viable alternative to taking their cars into Manhattan.

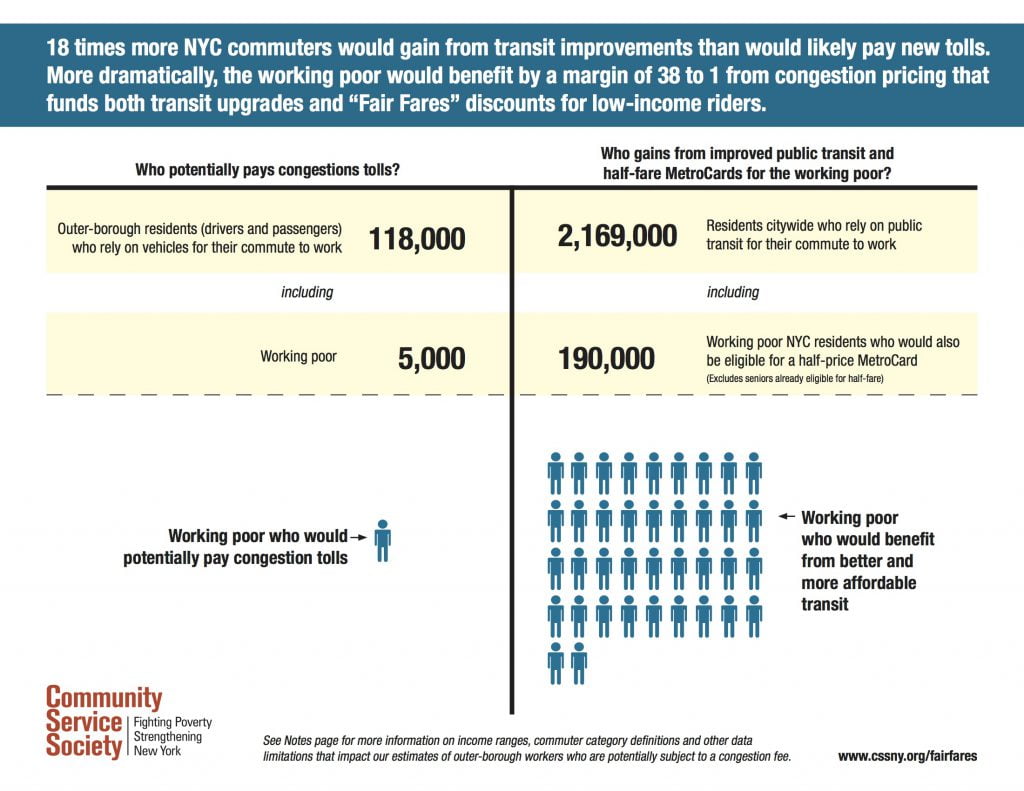

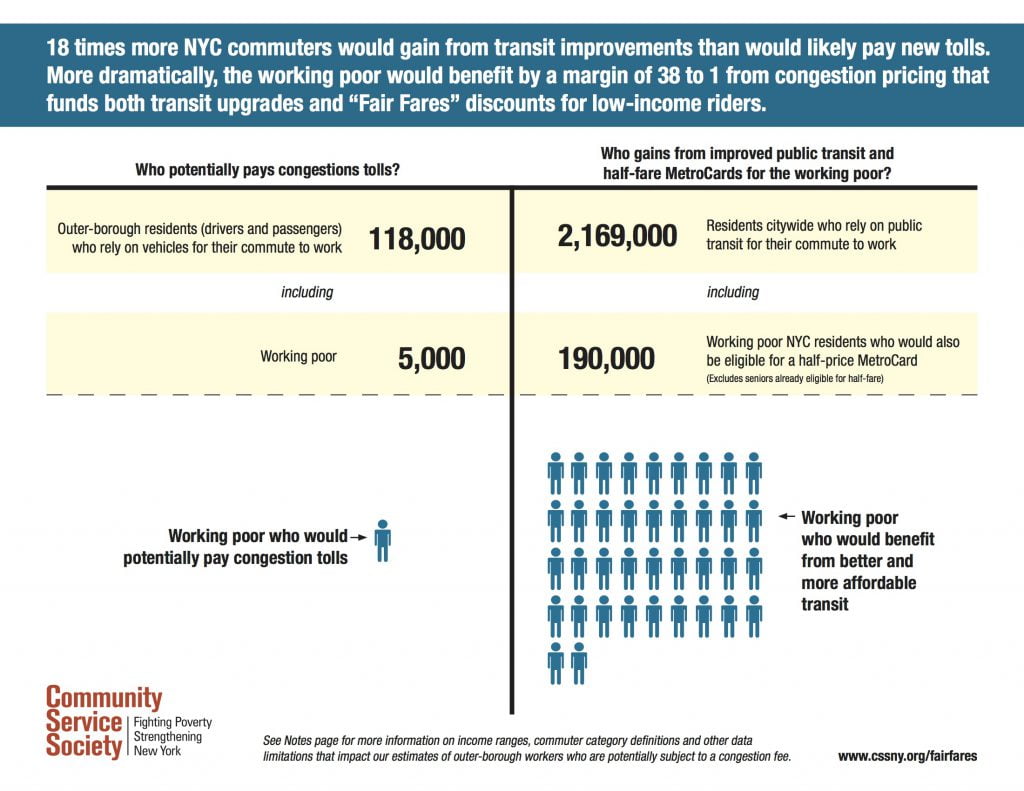

Mayor De Blasio has said he’s concerned that congestion pricing could disproportionately hurt low-income New York City residents. But a new report from the Community Service Society shows just the opposite. Low-income New Yorkers would disproportionately gain from congestion pricing that raised revenue for mass transit, and the costs would be primarily paid by those who can afford it most.

The study shows that only a small fraction of people living in the outer boroughs of New York City would find their commutes affected by the toll: four percent of the working people who live in the outer boroughs, and two percent of working poor. Many outer-borough residents have jobs in places other than Manhattan, and the large majority of those who do work in Manhattan come by public transportation. Overall, 118,000 people could wind up paying the toll. Of those, more than half are higher-income residents and over a quarter have moderate-income. Twelve percent are near poor, and four percent—5,000 people—are below the poverty line. (Near-poor is between the poverty line and double that income level; moderate income is between 200 and 400 percent of the poverty line; higher income is above that level.)

By contrast, 2.2 million New York City residents rely on public transit to get to work, including 190,000 working poor. If the system invested in fair fares, those 190,000 people would be able to take advantage of half-price subway rides.

We shouldn’t ignore the 5,000 working people living in poverty who could face an increase in the toll, some of whom do not have good alternatives for getting to work. But adding a cost or inconvenience for them is a tradeoff that makes sense considering the very substantial benefits to so many New Yorkers, including the benefit to a far larger number of working poor living in the outer boroughs.

The mayor should listen to his own appointee to the MTA board, David Jones, the president of the Community Service Society, which produced this report, and help explain that it disproportionately benefits lower-income New Yorkers.

And the governor should wake up to the urgency of funding to maintain and expand public transportation while keeping it affordable, and embrace the ideas of a millionaire’s tax and half-price fares for the lowest-income riders.

Maybe working together, these two Democrats could get more done in this state than by working at odds with each other.

Just saying.

By: David Dyssegaard Kallick

Congestion Pricing “vs.” Millionaire’s Tax: Why Not Do Both?

October 30, 2017 |

October 30, 2017.

Here’s a story you don’t hear every day: in the latest spat between Governor Andrew Cuomo and New York City Mayor De Blasio, both of them are right. Congestion pricing, the governor’s proposal, and a surcharge to the millionaire’s tax, the mayor’s proposal, are both good ideas.

The not-so-secret feuding between the governor and the mayor has not served New Yorkers well. From the serious to the petty, the two Democrats don’t seem to be able to get along about much. But, in their dueling proposals to provide much-needed funding to improve New York City’s transit system, they should get over their differences and say yes to both ideas.

The Mayor’s proposal is straightforward: increase the income tax on people who can most easily bear it, and who benefit from the city’s having a functioning public transit system whether or not they use it themselves. The governor called the mayor’s proposal “dead on arrival.” Well, the proposal would be looking a whole lot healthier if the state’s highest official were giving it a boost rather than trashing the idea.

The mayor’s proposal would generate revenue for transit upgrades, and also for “fair fares,” half-price subway entrance for low-income New Yorkers.

Meantime, Governor Cuomo has suggested revisiting the idea of congestion pricing on the bridges and tunnels coming into Manhattan, but the mayor says he does not believe in congestion pricing. That’s too bad. Congestion pricing is a good idea whose time has come. The governor hasn’t put out a specific proposal yet, but the general idea is to put a higher price on coming through the city’s bridges and tunnels at peak hours, and a lower price in off-peak times.

By giving drivers an incentive to use the crossings before or after rush hour, the bridges and tunnels would be used more efficiently and with less extreme backups at the entrances. And, of course, the funds raised would support the public transportation that would give at least some drivers a viable alternative to taking their cars into Manhattan.

Mayor De Blasio has said he’s concerned that congestion pricing could disproportionately hurt low-income New York City residents. But a new report from the Community Service Society shows just the opposite. Low-income New Yorkers would disproportionately gain from congestion pricing that raised revenue for mass transit, and the costs would be primarily paid by those who can afford it most.

The study shows that only a small fraction of people living in the outer boroughs of New York City would find their commutes affected by the toll: four percent of the working people who live in the outer boroughs, and two percent of working poor. Many outer-borough residents have jobs in places other than Manhattan, and the large majority of those who do work in Manhattan come by public transportation. Overall, 118,000 people could wind up paying the toll. Of those, more than half are higher-income residents and over a quarter have moderate-income. Twelve percent are near poor, and four percent—5,000 people—are below the poverty line. (Near-poor is between the poverty line and double that income level; moderate income is between 200 and 400 percent of the poverty line; higher income is above that level.)

By contrast, 2.2 million New York City residents rely on public transit to get to work, including 190,000 working poor. If the system invested in fair fares, those 190,000 people would be able to take advantage of half-price subway rides.

We shouldn’t ignore the 5,000 working people living in poverty who could face an increase in the toll, some of whom do not have good alternatives for getting to work. But adding a cost or inconvenience for them is a tradeoff that makes sense considering the very substantial benefits to so many New Yorkers, including the benefit to a far larger number of working poor living in the outer boroughs.

The mayor should listen to his own appointee to the MTA board, David Jones, the president of the Community Service Society, which produced this report, and help explain that it disproportionately benefits lower-income New Yorkers.

And the governor should wake up to the urgency of funding to maintain and expand public transportation while keeping it affordable, and embrace the ideas of a millionaire’s tax and half-price fares for the lowest-income riders.

Maybe working together, these two Democrats could get more done in this state than by working at odds with each other.

Just saying.

By: David Dyssegaard Kallick