Financing Affordable Multi-Family Housing Development

October 29, 2024 |

A Primer for State and Local Policymakers

Introduction

What does it cost to build a new home, and how do you pay for it? Many New York legislators are asking these questions as they stare down the large housing deficit faced by the State. It is widely agreed that New York suffers from too little housing, forcing the price of housing higher than New Yorkers can afford. With a housing supply crisis on our hands, policymakers must evaluate the reasons that housing construction hasn’t kept up with increasing demand, and devise solutions to accelerate housing construction so that New York can continue growing and housing its workforce.

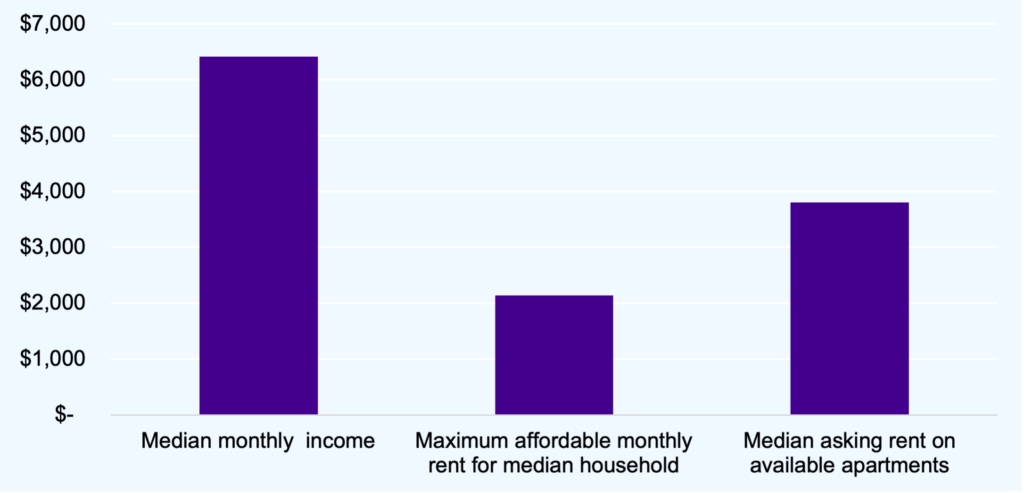

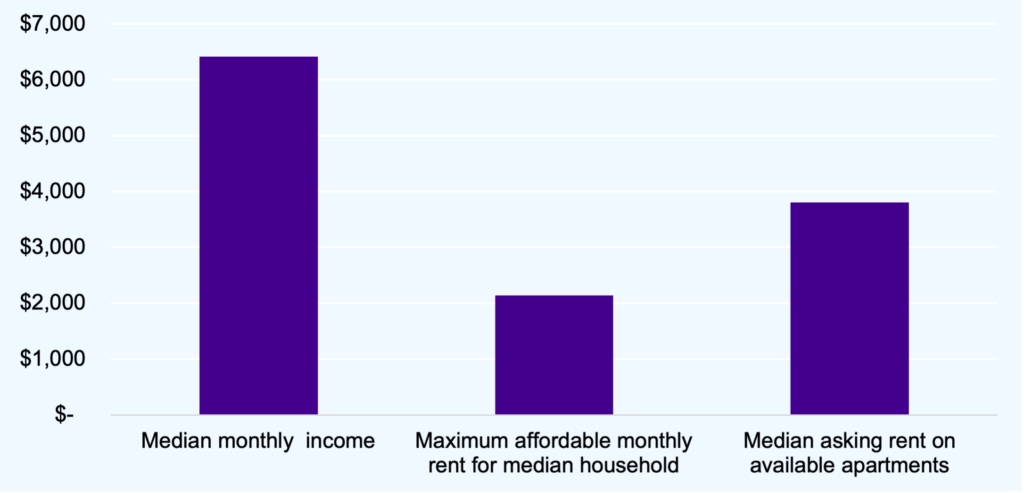

New York must focus on developing not only market-rate housing but also affordable housing that will ensure that New Yorkers of all socio-economic statuses can live comfortably and sustainably in the state. The need for affordable housing stems from the fact that many individuals and households in New York do not earn sufficient income to pay for market rate housing without facing a serious financial burden. For example, the median household in New York City earns approximately $77,000.[i] To avoid becoming rent burdened (i.e. spending over 30% of income on housing costs), the median New York City household can only spend about $2,000 per month on housing costs. However, as of June 2024, the median asking rent across New York City was $3,800 per month.[1][ii] With rents in the NYC metro area up over 200 percent since 2000 and up over 13 percent since the start of the pandemic, finding housing that fits family budgets has become increasingly challenging in New York.[iii] To ensure that housing stays affordable for working-class and middle-class New Yorkers, programs to develop affordable housing are increasingly needed.

This policy primer explains how new housing is financed, and how the New York State government can intervene to promote housing development, particularly of multi-family apartment buildings and affordable housing units.

Figure 1. Median monthly income and median monthly rent for New York City households.

The basics of building new multi-family housing

The process of building new housing in New York State is both lengthy and intricate. Current reports on the costs of building new housing in New York City find that new multi-family apartments cost between $330 per square foot and over $650 per square foot.[iv] Constructing a single apartment of 1,000 square feet can therefore cost between $330,000 and $650,000. These costs can be prohibitively high even for market-rate developers who will charge their occupants high rents or sell the units at full market price. For a government working to provide affordable housing to state and city residents, the high costs of building pose a serious policy problem. Understanding the costs of building can help policymakers develop tools and approaches to limiting the cost of housing development, thus providing more affordable housing options in the State.

The main costs of developing and operating a multi-family rental building can be broken down as follows:

- Land acquisition costs: the price of the plot that the new construction will be built on (and any buildings to be refurbished);

- Property taxes: taxes paid to the local government based on the assessed valuation of the building and local law;

- Construction costs: all costs directly related to constructing new housing including the cost of construction materials, the labor that is needed to build the house, a fixed fee paid to the developer of the new housing, and various other “soft costs” associated with the logistical process of building new housing (legal fees, marketing, etc.);

- Financing costs: In almost all cases, the developers building housing will need to take out a large loan from a bank to pay for all the up-front costs of construction before they are able to sell the building or lease the building and charge rents. The cost of the loan (the “financing cost”) is determined by the size of the loan and the interest rate on the loan;

- Operating costs: the cost of maintaining and managing the building once it is in use.

Finding ways to limit each of these costs contributes to the viability of building new housing. In the case of affordable housing, limiting costs is particularly important, as it creates more opportunity for offering the newly built units at below-market rents that are affordable for low-income households.

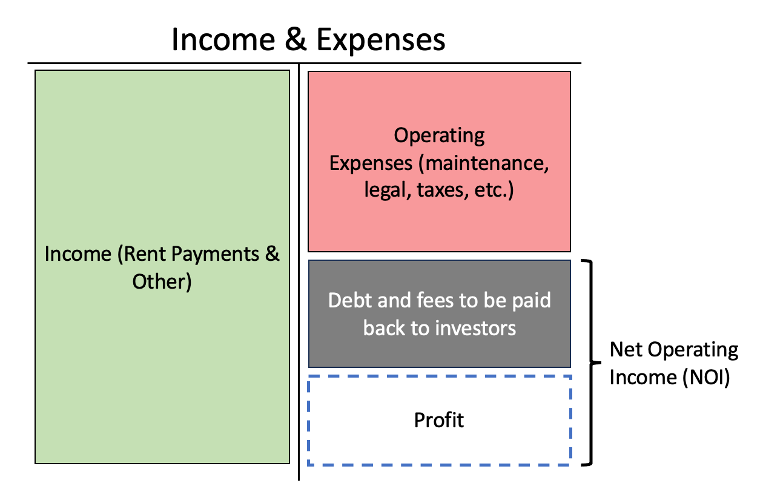

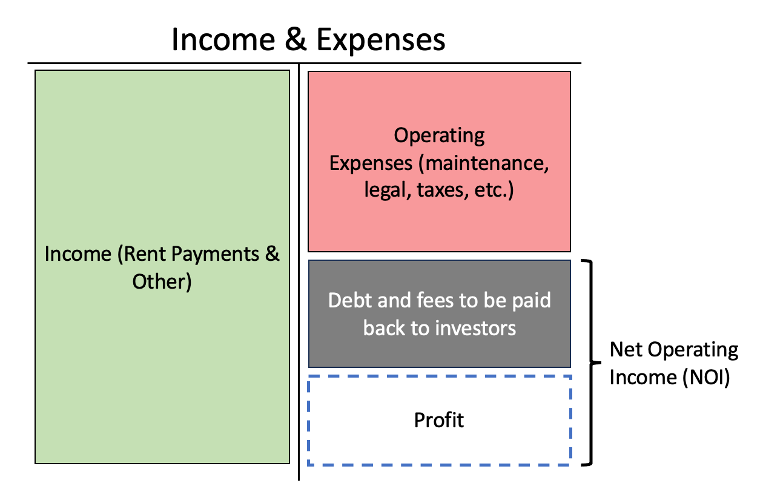

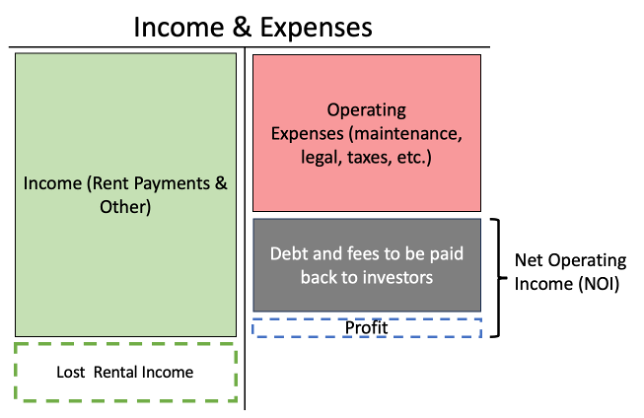

Housing developers say that a project “pencils out” (meaning it is financially viable) when the anticipated rental income will cover the expected costs of building the new development. Figure 2 gives an illustration of a multi-family housing development’s income and expenses once the development has been leased and is occupied by tenants. The primary source of income will be rent paid by tenants (green box), and the main operating expenses include building maintenance, insurance, legal fees, taxes, and other ongoing costs of operating a rental building (red box). The difference between income and expenses is deemed the “Net Operating Income” (NOI). The NOI is simply the net income of the building’s operations before paying costs associated with project financing. All financing costs — primarily debt repayments to investors (grey box) – are taken out of the NOI, leaving the remainder as profit to the building owners (box indicated by dashed blue line). If the NOI is not large enough to pay the monthly debt payments — that is, if the financing costs are larger than the difference between income and operating expenses — then the project does not “pencil” and will not be built. To ensure that there will be enough NOI to pay off the incurred debt, policymakers can increase the income of the housing development, via direct subsidization, or decrease the expenses or financing costs.

Figure 2. Illustration of the income and expenses of an operational multi-family housing development.

Financing costs determine the viability and affordability of new housing

Among other costs, the size of debt payments needed to repay investors plays a large role in determining the viability of a housing project. To understand the crucial role that financing plays, we can look at an illustration of the monthly finances of a new housing development once it has reached the operational stage and is generating rental income, as depicted in Figures 2-4. For many housing developments, debt payments on loans used to finance construction and land acquisition can last about 30 years, like a typical mortgage. Over the life of the loan, the housing development must have enough income — either in rent or in subsidies, as we’ll return to later — that the owner can repay their debt. Once the debt is paid off, there are no longer monthly payments to be made to the bank, and the entirety of the net operating income becomes profit for the owners.

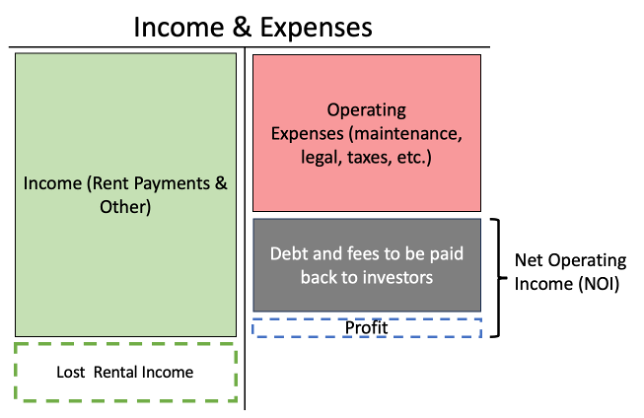

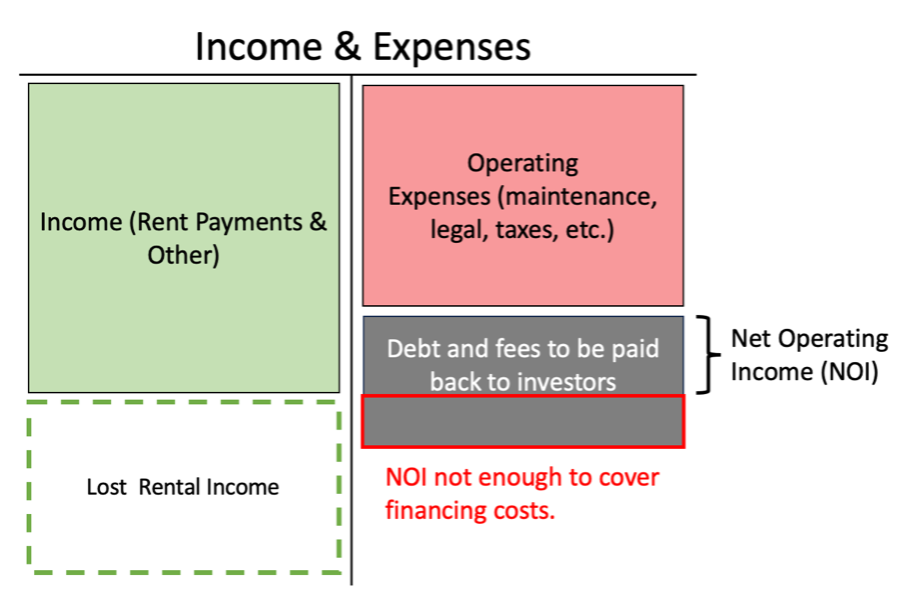

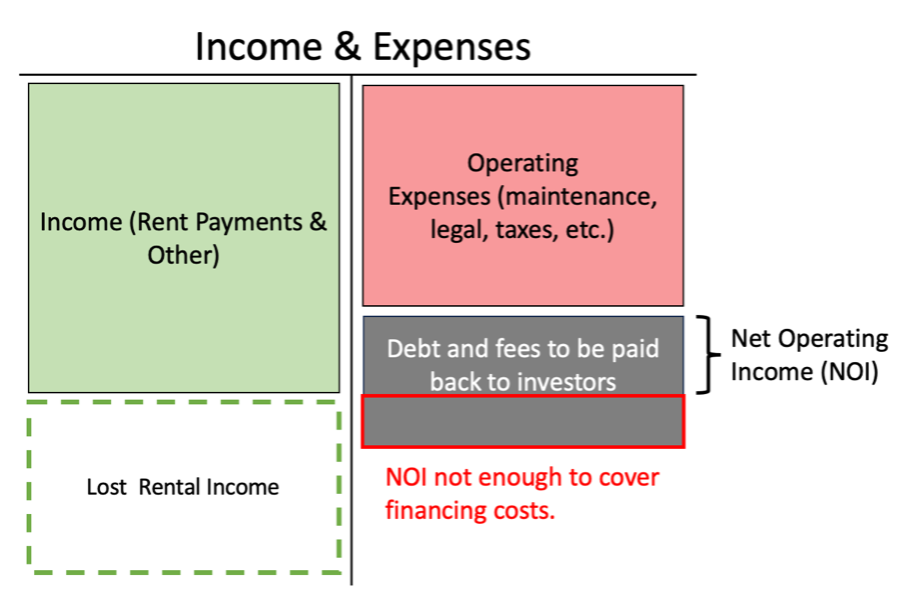

While Figure 2 depicts a new housing development that can afford to pay its debt and still turn a profit, most housing developments with affordability standards have far less revenue, and thus do not earn profit. Frequently, depending on the applicable affordability standards, these projects may not bring in enough revenue to repay their debt from the construction process. Figures 3 and 4 depict the cases of housing developments that lose rental income due to affordability standards, and thus either turn a near-zero profit or cannot even repay the debt they accrued during the construction process. These models demonstrate that by decreasing the size of the debt repayment, new housing developments can more easily afford to charge lower rents.

Figure 3. Example financing plan for affordable multifamily rental construction project.

Figure 4. Example financing plan for affordable multifamily rental construction project that is not viable without policy intervention.

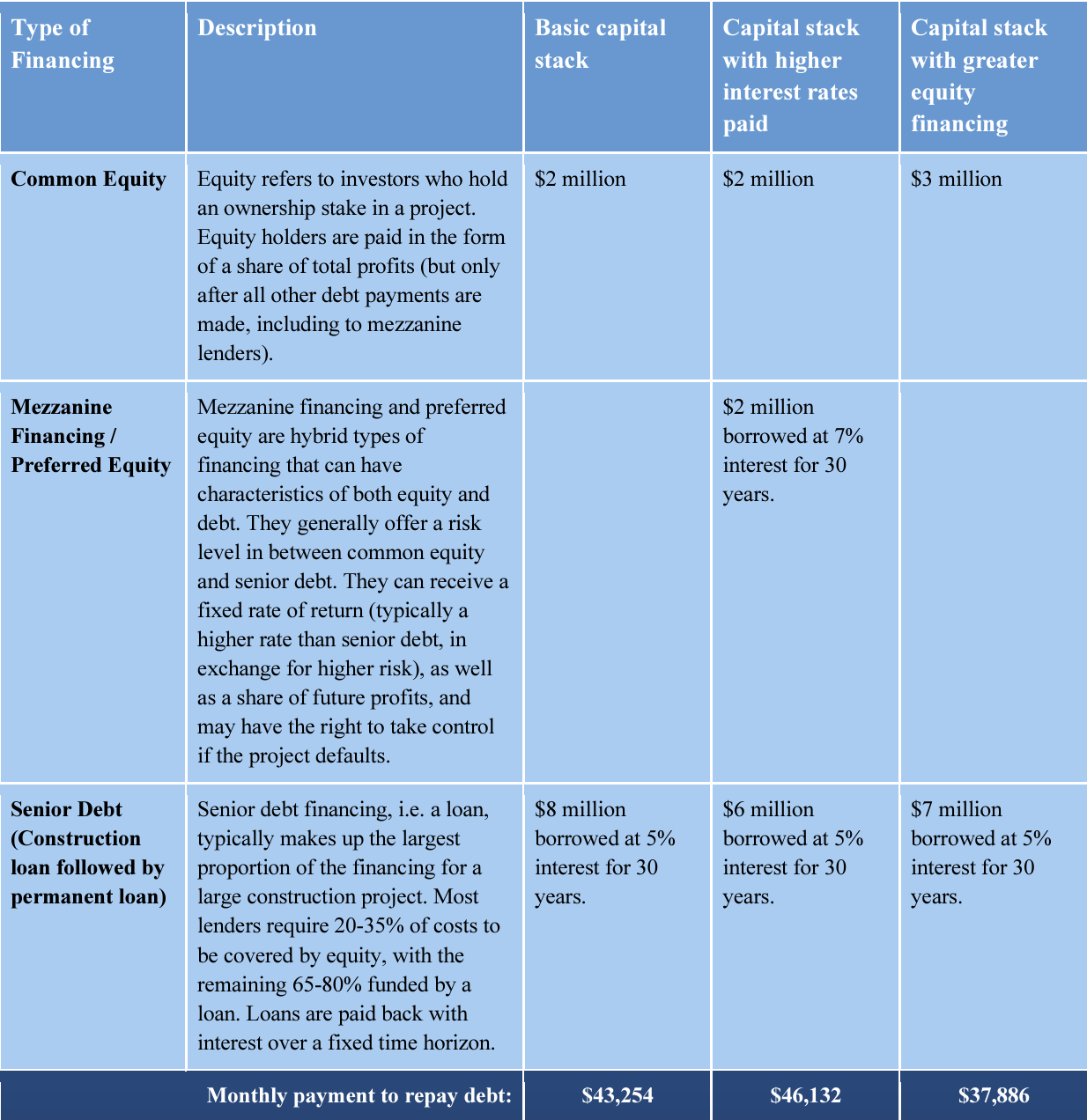

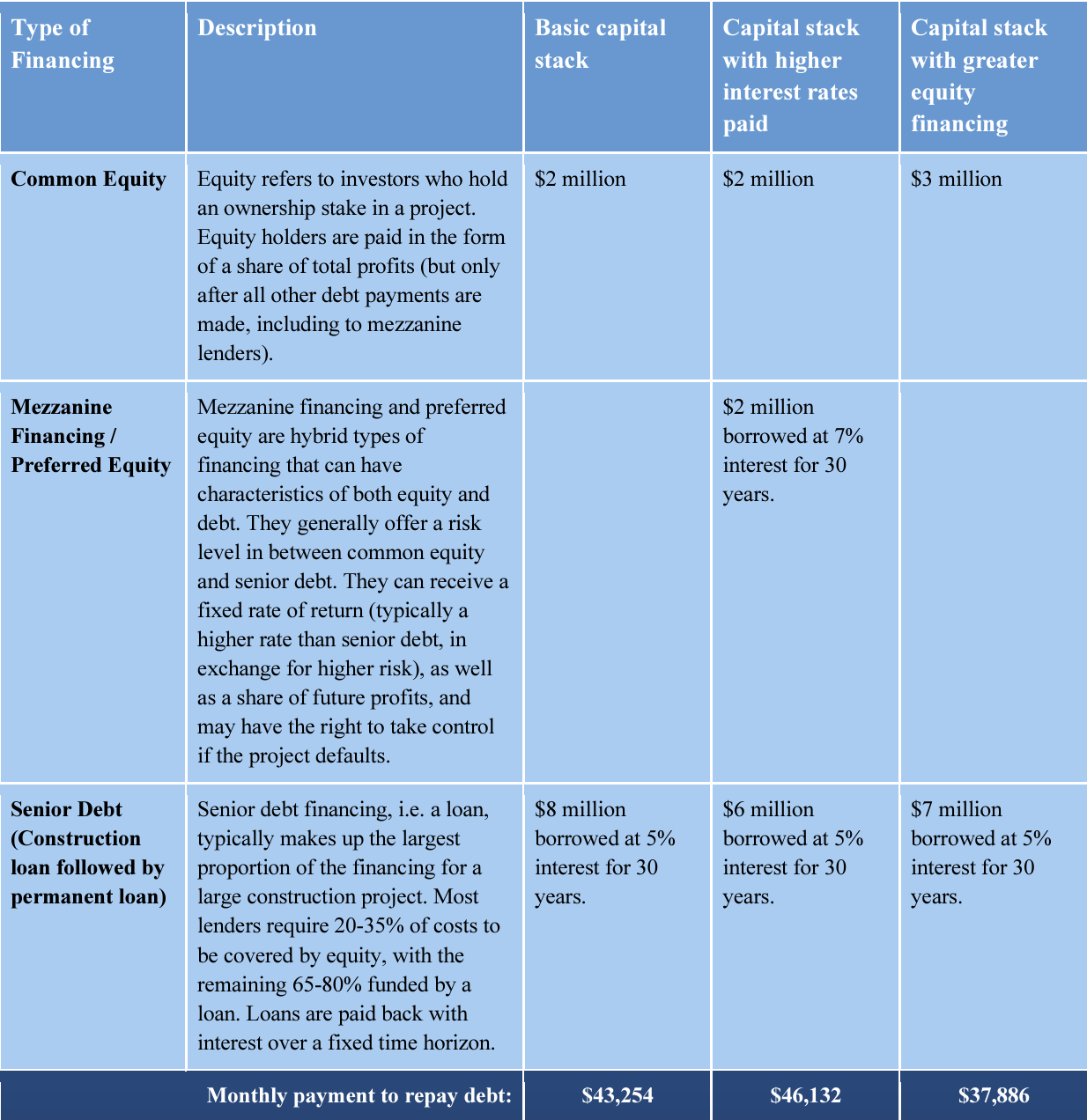

Tools that limit the size of these payments can dramatically increase the affordability of new housing. Table 1 provides examples for how a $10 million housing development project could be financed. A project that has a greater amount of equity financing will cost less, all else equal, than a project with less equity financing. Similarly, a project that receives a loan at a high interest rate will be more expensive than a project that receives a loan at a low interest rate.

By intervening in the financing of affordable housing development, government can reduce the debt repayment costs associated with developing new housing, therefore reducing the rental income needed to make the development viable.

Table 1. Example financing plans for construction project with $10 million in construction costs.

Policy tools for financing affordable housing in New York

To alleviate the housing affordability crisis in the state, New York policymakers should consider using a series of tools to expand the supply of both market-rate and affordable housing. Expanding housing supply for tenants and residents across the income distribution is an essential role for the state government and will require action on multiple policy axes.

Leveraging Federal Policy: Housing Choice Vouchers and Tenant Protection Vouchers

The standard Section 8 voucher program delivers vouchers to low-income households so that they can find and pay for suitable rental housing on the private market (i.e. from the same landlords as those without vouchers). However, some housing choice vouchers can be set aside to be used at a specific housing project that will accept low-income tenants. These vouchers are called “project-based vouchers” because they provide secure funding to a specific affordable housing development. Project-based vouchers increase the anticipated revenue of an affordable housing project by ensuring that revenue will be sufficiently high to pay for the project’s ongoing costs (operating costs and financing costs).

In recent years, Section 8 vouchers, specifically those that are project-based, have started to play a fundamental role in the affordable housing infrastructure of New York City. With New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) housing stock chronically under-funded, the Authority has sought federal funding support. Support for NYCHA in recent years has largely taken the form of dedicated section 8 housing vouchers. For example, the Permanent Affordability Commitment Together (PACT) program that NYCHA is using to renovate and expand some of the Authority’s housing developments is part of the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) program called the Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD) which dedicates Section 8 housing vouchers to a NYCHA development as a permanent funding stream.[v] By providing Section 8 vouchers to support the funding of NYCHA’s public housing, HUD is bolstering NYCHA’s income stream, thereby increasing its ability to obtains loans (secured by its increased Section 8 voucher revenue). These loans then enable NYCHA to make much-needed renovations and expansions.

NYCHA has also created a “Preservation Trust” for other housing developments, which will allow the agency to access what are called “Tenant Protection Vouchers,” another type of federal Section 8 voucher that NYCHA can use to increase its revenue and thereby finance needed infrastructure improvements.[vi]

Project-based Section 8 vouchers are an important tool for securing reliable revenue for an affordable housing development. Most, if not all, of these vouchers must be allocated by public housing authorities, such as NYCHA, around the state and in coordination with HUD.

Leveraging Federal Policy: The Low-Income Housing Tax Credit

The second major source of affordable housing support from the federal government comes in the form the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC). These tax credits are distributed to affordable housing developers in the State and then used by the housing developers to lower their overall costs, thereby allowing them to charge less in rent. Decreasing the “expense” side of their budgets permits them to also decrease the “income” side.

However, the way this works is a bit complicated. The idea is that the private housing developer (whether for-profit or not-for-profit) needs some reduction in their overall costs to make it possible to build housing with affordable units. To lower costs, the developer is awarded a large tax credit that they can use against their tax liabilities for the next 10 years. However, housing developers do not always have large tax liabilities, in which case the tax credit is less valuable to them (especially in the case of a non-profit developer with no tax liability). Instead of using the tax credit themselves, affordable housing developers sell the tax credit to a private investor in exchange for an equity investment in the project. The private investor receives the full value of the tax credits to claim on their own taxes, plus an equity share in the development, in return for providing up-front cash to the developer that will not need to be paid back as a loan would. Now the private investor can claim the tax credit and lower their tax payments to the federal government, and the housing developer has more cash to invest in the project as equity. By selling the tax credit to a private investor and increasing the equity investment in the development, the housing developer can take a smaller loan from the bank and thus has a smaller monthly payment to make to the bank over the life of the loan (as illustrated in Table 1 above). The housing developer can thus afford to charge sub-market rental rates to lower-income tenants. This can be understood as a reduction in the financing costs of the housing developer. By reducing financing costs, the affordable housing developer can reduce rents to “affordable” rates.

The Low-Income Housing Tax Credit has decreased in value over recent years, possibly because investors have less interest in buying the credits from housing developers. Without investor demand for the tax credits, housing developers cannot effectively reduce costs. Finding new ways to either bolster LIHTC or find new funding sources is of key importance for policymakers.

Direct Capital Expenditures

The most intuitive tool that the State can use to fund new affordable housing development is investing directly in housing projects, i.e. devoting financial resources directly into building and maintaining affordable housing. These expenditures can be invested in new State-owned housing or can take the form of subsidies or grants to private developers.

To see how direct government spending on housing development could work, imagine the State were to allocate $5 billion in capital towards new affordable housing developments. If the State chooses not to borrow additional funds, $5 billion in capital expenditures can build between 10,000 and 20,000 units of housing at current costs (each unit costs between $250,000 and $500,000 to build). Once construction is finished, the State would have to fund ongoing operations and building maintenance. Depending on the rents charged to tenants, the State may need to supplement rental payments with ongoing operating funds. If the housing is kept in good condition and used for mixed-income housing, rather than 100 percent affordable housing, then it is possible for the State to operate the housing without operating subsidies, or even possibly at a profit, yielding additional revenue that could be used to continue expanding housing development.

In the case described above, the State is acting as the primary funder and owner of the housing development. However, the State can also give grants and subsidies to owners and developers of housing without taking an ownership stake itself. There are many examples of such government expenditures in New York. For example, New York City’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) gives grants directly to non-profit developers of low-income housing that are either constructing or developing new housing in the City. By delivering grants to developers, the city directly decreases the developers’ needs for debt financing and thus reduces the monthly debt repayment fee paid by the developer. By reducing financing costs, the housing development can increase affordability of housing units created.

Tax-Exempt and Taxable Bonds

The State can also borrow funds, typically by issuing either taxable or tax-exempt bonds. These bonds are issued by the State, bought by private bond investors, and paid back over time through tax revenue. In the case of tax-exempt bonds, the investor’s interest on the bond is tax-exempt, allowing the State to offer the bond at a lower interest rate, and thus reducing the State’s overall costs. Again, by reducing costs, the State can build more affordable housing units.

Imagine the State were to issue $20 billion in bonds, to be sold to investors and paid back over time. At current construction prices in New York, $20 billion in capital funds could build between 40,000 and 80,000 homes (assuming each unit costs between $250,000 and $500,000 to build). The State would then need to pay back the $20 billion borrowed plus the coupon rate — i.e. the interest rate — on the bond using either tax revenue or rental revenue. Unless there is a tax-funded revenue stream, these debt repayments would weaken the State’s ability to offer the units at affordable rents, demonstrating the affordability-financing trade off discussed previously. However, to the extent that the State can drive down construction, land-acquisition and financing costs, these housing developments may be able to attain more affordability than typical market-rate housing. Certainly, the tax-exempt nature of the bond financing in many cases decreases the interest rate on the bond and reduces the overall cost burden of the financing.

The State can and does also deploy tax-exempt bond financing to support low-cost lending to private housing developers. This will be discussed further in the next section.

Government lending to private developers: The Montgomery County Model

Another tool that can be used by the government to promote housing construction is a government lending facility that offers low-cost financing to housing developers. Because the government can loan funds at relatively low interest rates, the government can reduce the cost of financing for affordable housing developers. This is particularly important when high interest rates are making financing challenging for developers, as has been the case in recent years.

Montgomery County, Maryland has received recognition recently for its creation of a revolving loan fund to help finance new multi-family housing with affordable units. It is projected that by efficiently deploying the capital raised by a $100 million municipal bond issuance, Montgomery County will be able to build 1,500 units of new housing every five years on a continual basis. With a small return on the loans they provide to developers, the total cost to the county of building this new mixed-income housing is only $2.7 million annually. Here’s how this works:

- First, Montgomery County issues $100 million in bonds. The bonds are sold on the municipal bond market, and the bondholders are entitled to interest payments that costs the County $7.7 million each year for 20 years;

- The County uses the $100 million that it received from the sale of the bond as financing for private developers that need cash during the construction process. This eliminates the need for a construction loan, which can be more expensive on the private market. By borrowing from the government instead, the private developer reduces the cost of construction, and thus the long-term financing costs of the project;

- Once the construction process is complete and the buildings are leased-up, the private developer fully pays back the loan principle to the County, plus five percent interest (five percent interest on $100 million is $5 million). At this stage, the County has recovered the original $100 million, plus interest income of $5 million per year, and owes bond investors $7.7 million per year. On net, the County government then needs to raise another $2.7 million per year to pay its bond investors.

This process creates about 1,500 units of housing every five years at a cost of $13.5 million to taxpayers. Montgomery County also uses a mixed-income model to cross-subsidize for affordability. A typical project rents 70 percent of its units at the market rental rate, and rents out the remaining 30 percent of units to be affordable to families earning below 80 percent of the area median income. With this income mix, the overall public cost is $30,000 for each permanently affordable unit and no cost for the market-rate units.

Once a project has been leased up and the $100 million loan repaid, the County can repeat the construction process, creating more housing units with the same initial loan fund and low cost to taxpayers. After twenty years, the bond investors will be paid off and the County will be operating at a profit, allowing either more units or deeper affordability levels.

Ultimately, by reducing the cost of financing for the housing development, the County is ensuring that the housing can sustain some level of affordability for renters. Additionally, the County puts downward pressure on the cost of financing by competing with private lenders. This has the potential impact of reducing financing costs across the entire market.

At an investment of $100 million, the Montgomery County model can only feasibly support the building of a few hundred units per year (1,500 every five years). However, if financed at $1 billion, as could be achieved in New York, a revolving lending facility of this sort could support the construction of a few thousand units per year at very low long-term cost to New York taxpayers. The level of affordability that could be attained under this model depends on the rate of interest charged by the government relative to the rate of interest charged by private developers.

Tax Incentives

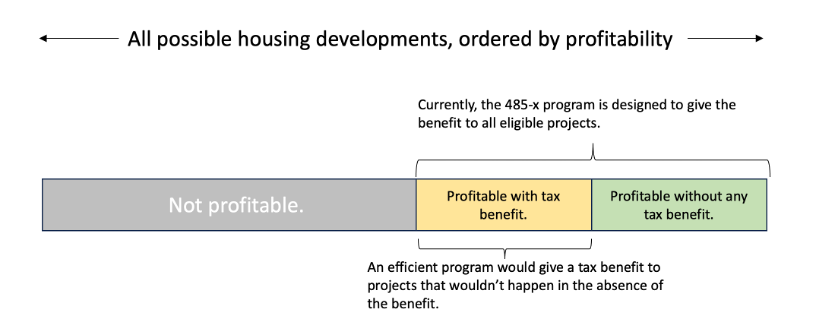

Tax incentives – also known as “tax expenditures” and “tax benefits” – have been widely used in recent history for many policy purposes including affordable housing, economic development, and efforts to move towards more renewable energy production. In the case of a tax expenditure, the state or federal government lowers the tax liabilities of entities that take on certain publicly desirable business activities. For example, the government may desire the production of more housing than is currently profitable. To stimulate additional building, the government would lower the tax liability of housing developers so that a greater amount of housing becomes profitable to build. In Figures 2-4, this corresponds to decreasing the size of the red/pink “Expenses” box, which increases the overall Net Operating Income and thus the profitability of the project. This makes it possible to create more affordable housing by lowering the cost of construction and building operating expenses.

As discussed above, the LIHTC is a federal tax credit policy intended to lower the cost of developing affordable rental housing. In New York City, the long-standing 421-a tax credit has been used to incentivize developers to build multi-family apartment buildings that have some income-restricted units and was recently renewed under the name Affordable Neighborhoods for New Yorkers (a.k.a. 485-x) in the fiscal year 2025 state budget. The fiscal year 2025 state budget also included an upstate tax incentive policy (421-p) and a tax credit for commercial conversion in New York City (467-m).

The 421-a tax credit (now replaced by 485-x) was originally put into place in the 1970s, at which point the intent of the policy was to promote the construction of market rate housing, with no required affordability requirements. Over time, the policy evolved to include affordability requirements for participating housing developments. In a 2022 report, the New York City Comptroller’s office found that foregone tax revenue amounted to between $1.7 billion and $1.8 billion each year between 2019 and 2022.[vii] The report found that over the years 2017-2020, a total of 14,874 housing units were built under 421-a, with only 4,456 of those units deemed “affordable.” Over 60 percent of all units deemed affordable were for families whose incomes were for families making 130 percent of the area median income (well over $100,000/year in annual income). The Comptroller’s office found that New York City foregoes over $60,000 annually for 35 years for each unit of affordable housing. For each unit that is affordable to those making less than 60 percent of the area median income, the city foregoes over $120,000 annually for 35 years. These expenses far exceed the expenses of both section 8 vouchers and NYCHA’s section 9 public housing. However, the program is also subsidizing new housing stock, rather than simply sustaining tenants in already-existing housing stock. Interpreting these costs in the context of the housing supply crisis in New York City is challenging and requires a deeper look into the cost of construction in the city.

For a state or locality that lacks enough tax revenue to directly spend on affordable housing development, a tax incentive might make sense; there isn’t tax revenue enough to spend directly, but offering a tax incentive might enable development that would not otherwise take place. Small municipalities and local governments often fall into this category because they lack sufficient funds to front-load their costs with cash that they have on hand or can reliably raise over a short time horizon. The tax incentive can attract private capital and developers to undertake a project that the government wants and otherwise would not be profitable.

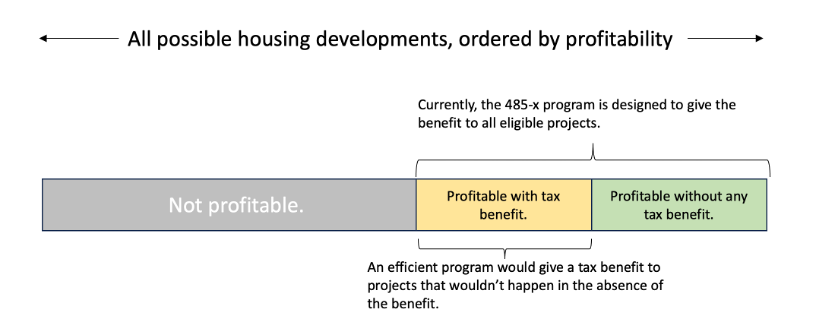

However, tax incentives can easily result in waste if the development would have occurred even in the absence of the policy. Distributing tax incentives using a competitive process that ensures that the incentives will be used to create otherwise financially infeasible projects is essential to a successful policy. This mechanism is notably lacking in programs like 421-a that operate as-of-right, meaning that all eligible projects will receive the benefit, regardless of whether they need the benefit to be viable. Tax abatement also has the side effect of lowering the capacity of the government to build expertise, raise revenue, and undertake large scale capital projects.

Figure 5. Diagram illustrating the allocation of tax benefits to housing developers by project profitability.

Conclusion

By developing new financing tools and leveraging public assets, New York State can support the robust provision of affordable housing in the state. This is increasingly urgent as families leave in search of greater affordability. To increase housing affordability in the State, policymakers must develop plans to increase the provision of multi-family affordable housing. To do this requires an understanding of how housing developments are financed, what the major costs of development are, and what policy tools the State can use to alleviate costs.

The major costs of developing and operating new multifamily housing include land acquisition costs, construction costs (which includes construction materials, labor, and other soft costs), property taxes, financing costs (the cost of repaying any outside investment in the property), and ongoing operating costs (building maintenance, marketing, etc.). Investigating each of these costs can provide opportunities for state intervention to lower costs, thereby increasing the overall provision of housing and the potential for affordability.

Financing costs — i.e. the cost of borrowing funds to pay for the up-front costs of development — offer a key lever for the State to promote the provision of new multi-family housing and make affordable units more readily available across the state. By leveraging already-existing policy tools, such as Federal Housing Choice Vouchers and the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit, and developing new innovative approaches to limiting financing costs for housing development, as has been pioneered in places like Montgomery County, Maryland, New York State can promote multi-family housing development that includes affordability standards. Mitigating financing costs also has the long-term benefit of smoothing the cyclicality of housing construction in the State, which will play a large role in meeting the housing supply needs that are currently far from met.

[1] Median asking rent is distinct from the median observed rent. The median asking rent only considers housing units that are currently listed as “for rent,” whereas the median observed rent would include all units regardless of whether they are currently listed as available on the market.

[i] US Census Bureau, “Quick Facts,” https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/newyorkcitynewyork/HSG010222

[ii] StreetEasy Data Dashboard, https://streeteasy.com/blog/data-dashboard/?agg=Median&metric=Asking%20Rent&type=Rentals&bedrooms=Any%20Bedrooms&property=Any%20Property%20Type&minDate=2010-01-01&maxDate=2024-06-01&area=Flatiron,Brooklyn%20Heights

[iii] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers: Rent of Primary Residence in New York-Newark-Jersey City, NY-NJ-PA (CBSA) [CUURA101SEHA], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CUURA101SEHA, June 17, 2024.

[iv] https://www.buildingcongress.com/uploads/COU_-_NYC_Construction_Costs_v5_digital_distro.pdf

[v] The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, “Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD)” https://www.hud.gov/RAD

[ii] The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, “Tenant Protection Vouchers” https://www.hud.gov/program_offices/public_indian_housing/programs/hcv/tenant_protection_vouchers

[vii] “A Better Way Than 421-a: The High-Rising Costs of New York City’s Unaffordable Tax Exemption Program,” March 16, 2022. https://comptroller.nyc.gov/reports/a-better-way-than-421a/#_ftnref23

Financing Affordable Multi-Family Housing Development

October 29, 2024 |

A Primer for State and Local Policymakers

Introduction

What does it cost to build a new home, and how do you pay for it? Many New York legislators are asking these questions as they stare down the large housing deficit faced by the State. It is widely agreed that New York suffers from too little housing, forcing the price of housing higher than New Yorkers can afford. With a housing supply crisis on our hands, policymakers must evaluate the reasons that housing construction hasn’t kept up with increasing demand, and devise solutions to accelerate housing construction so that New York can continue growing and housing its workforce.

New York must focus on developing not only market-rate housing but also affordable housing that will ensure that New Yorkers of all socio-economic statuses can live comfortably and sustainably in the state. The need for affordable housing stems from the fact that many individuals and households in New York do not earn sufficient income to pay for market rate housing without facing a serious financial burden. For example, the median household in New York City earns approximately $77,000.[i] To avoid becoming rent burdened (i.e. spending over 30% of income on housing costs), the median New York City household can only spend about $2,000 per month on housing costs. However, as of June 2024, the median asking rent across New York City was $3,800 per month.[1][ii] With rents in the NYC metro area up over 200 percent since 2000 and up over 13 percent since the start of the pandemic, finding housing that fits family budgets has become increasingly challenging in New York.[iii] To ensure that housing stays affordable for working-class and middle-class New Yorkers, programs to develop affordable housing are increasingly needed.

This policy primer explains how new housing is financed, and how the New York State government can intervene to promote housing development, particularly of multi-family apartment buildings and affordable housing units.

Figure 1. Median monthly income and median monthly rent for New York City households.

The basics of building new multi-family housing

The process of building new housing in New York State is both lengthy and intricate. Current reports on the costs of building new housing in New York City find that new multi-family apartments cost between $330 per square foot and over $650 per square foot.[iv] Constructing a single apartment of 1,000 square feet can therefore cost between $330,000 and $650,000. These costs can be prohibitively high even for market-rate developers who will charge their occupants high rents or sell the units at full market price. For a government working to provide affordable housing to state and city residents, the high costs of building pose a serious policy problem. Understanding the costs of building can help policymakers develop tools and approaches to limiting the cost of housing development, thus providing more affordable housing options in the State.

The main costs of developing and operating a multi-family rental building can be broken down as follows:

- Land acquisition costs: the price of the plot that the new construction will be built on (and any buildings to be refurbished);

- Property taxes: taxes paid to the local government based on the assessed valuation of the building and local law;

- Construction costs: all costs directly related to constructing new housing including the cost of construction materials, the labor that is needed to build the house, a fixed fee paid to the developer of the new housing, and various other “soft costs” associated with the logistical process of building new housing (legal fees, marketing, etc.);

- Financing costs: In almost all cases, the developers building housing will need to take out a large loan from a bank to pay for all the up-front costs of construction before they are able to sell the building or lease the building and charge rents. The cost of the loan (the “financing cost”) is determined by the size of the loan and the interest rate on the loan;

- Operating costs: the cost of maintaining and managing the building once it is in use.

Finding ways to limit each of these costs contributes to the viability of building new housing. In the case of affordable housing, limiting costs is particularly important, as it creates more opportunity for offering the newly built units at below-market rents that are affordable for low-income households.

Housing developers say that a project “pencils out” (meaning it is financially viable) when the anticipated rental income will cover the expected costs of building the new development. Figure 2 gives an illustration of a multi-family housing development’s income and expenses once the development has been leased and is occupied by tenants. The primary source of income will be rent paid by tenants (green box), and the main operating expenses include building maintenance, insurance, legal fees, taxes, and other ongoing costs of operating a rental building (red box). The difference between income and expenses is deemed the “Net Operating Income” (NOI). The NOI is simply the net income of the building’s operations before paying costs associated with project financing. All financing costs — primarily debt repayments to investors (grey box) – are taken out of the NOI, leaving the remainder as profit to the building owners (box indicated by dashed blue line). If the NOI is not large enough to pay the monthly debt payments — that is, if the financing costs are larger than the difference between income and operating expenses — then the project does not “pencil” and will not be built. To ensure that there will be enough NOI to pay off the incurred debt, policymakers can increase the income of the housing development, via direct subsidization, or decrease the expenses or financing costs.

Figure 2. Illustration of the income and expenses of an operational multi-family housing development.

Financing costs determine the viability and affordability of new housing

Among other costs, the size of debt payments needed to repay investors plays a large role in determining the viability of a housing project. To understand the crucial role that financing plays, we can look at an illustration of the monthly finances of a new housing development once it has reached the operational stage and is generating rental income, as depicted in Figures 2-4. For many housing developments, debt payments on loans used to finance construction and land acquisition can last about 30 years, like a typical mortgage. Over the life of the loan, the housing development must have enough income — either in rent or in subsidies, as we’ll return to later — that the owner can repay their debt. Once the debt is paid off, there are no longer monthly payments to be made to the bank, and the entirety of the net operating income becomes profit for the owners.

While Figure 2 depicts a new housing development that can afford to pay its debt and still turn a profit, most housing developments with affordability standards have far less revenue, and thus do not earn profit. Frequently, depending on the applicable affordability standards, these projects may not bring in enough revenue to repay their debt from the construction process. Figures 3 and 4 depict the cases of housing developments that lose rental income due to affordability standards, and thus either turn a near-zero profit or cannot even repay the debt they accrued during the construction process. These models demonstrate that by decreasing the size of the debt repayment, new housing developments can more easily afford to charge lower rents.

Figure 3. Example financing plan for affordable multifamily rental construction project.

Figure 4. Example financing plan for affordable multifamily rental construction project that is not viable without policy intervention.

Tools that limit the size of these payments can dramatically increase the affordability of new housing. Table 1 provides examples for how a $10 million housing development project could be financed. A project that has a greater amount of equity financing will cost less, all else equal, than a project with less equity financing. Similarly, a project that receives a loan at a high interest rate will be more expensive than a project that receives a loan at a low interest rate.

By intervening in the financing of affordable housing development, government can reduce the debt repayment costs associated with developing new housing, therefore reducing the rental income needed to make the development viable.

Table 1. Example financing plans for construction project with $10 million in construction costs.

Policy tools for financing affordable housing in New York

To alleviate the housing affordability crisis in the state, New York policymakers should consider using a series of tools to expand the supply of both market-rate and affordable housing. Expanding housing supply for tenants and residents across the income distribution is an essential role for the state government and will require action on multiple policy axes.

Leveraging Federal Policy: Housing Choice Vouchers and Tenant Protection Vouchers

The standard Section 8 voucher program delivers vouchers to low-income households so that they can find and pay for suitable rental housing on the private market (i.e. from the same landlords as those without vouchers). However, some housing choice vouchers can be set aside to be used at a specific housing project that will accept low-income tenants. These vouchers are called “project-based vouchers” because they provide secure funding to a specific affordable housing development. Project-based vouchers increase the anticipated revenue of an affordable housing project by ensuring that revenue will be sufficiently high to pay for the project’s ongoing costs (operating costs and financing costs).

In recent years, Section 8 vouchers, specifically those that are project-based, have started to play a fundamental role in the affordable housing infrastructure of New York City. With New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) housing stock chronically under-funded, the Authority has sought federal funding support. Support for NYCHA in recent years has largely taken the form of dedicated section 8 housing vouchers. For example, the Permanent Affordability Commitment Together (PACT) program that NYCHA is using to renovate and expand some of the Authority’s housing developments is part of the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) program called the Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD) which dedicates Section 8 housing vouchers to a NYCHA development as a permanent funding stream.[v] By providing Section 8 vouchers to support the funding of NYCHA’s public housing, HUD is bolstering NYCHA’s income stream, thereby increasing its ability to obtains loans (secured by its increased Section 8 voucher revenue). These loans then enable NYCHA to make much-needed renovations and expansions.

NYCHA has also created a “Preservation Trust” for other housing developments, which will allow the agency to access what are called “Tenant Protection Vouchers,” another type of federal Section 8 voucher that NYCHA can use to increase its revenue and thereby finance needed infrastructure improvements.[vi]

Project-based Section 8 vouchers are an important tool for securing reliable revenue for an affordable housing development. Most, if not all, of these vouchers must be allocated by public housing authorities, such as NYCHA, around the state and in coordination with HUD.

Leveraging Federal Policy: The Low-Income Housing Tax Credit

The second major source of affordable housing support from the federal government comes in the form the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC). These tax credits are distributed to affordable housing developers in the State and then used by the housing developers to lower their overall costs, thereby allowing them to charge less in rent. Decreasing the “expense” side of their budgets permits them to also decrease the “income” side.

However, the way this works is a bit complicated. The idea is that the private housing developer (whether for-profit or not-for-profit) needs some reduction in their overall costs to make it possible to build housing with affordable units. To lower costs, the developer is awarded a large tax credit that they can use against their tax liabilities for the next 10 years. However, housing developers do not always have large tax liabilities, in which case the tax credit is less valuable to them (especially in the case of a non-profit developer with no tax liability). Instead of using the tax credit themselves, affordable housing developers sell the tax credit to a private investor in exchange for an equity investment in the project. The private investor receives the full value of the tax credits to claim on their own taxes, plus an equity share in the development, in return for providing up-front cash to the developer that will not need to be paid back as a loan would. Now the private investor can claim the tax credit and lower their tax payments to the federal government, and the housing developer has more cash to invest in the project as equity. By selling the tax credit to a private investor and increasing the equity investment in the development, the housing developer can take a smaller loan from the bank and thus has a smaller monthly payment to make to the bank over the life of the loan (as illustrated in Table 1 above). The housing developer can thus afford to charge sub-market rental rates to lower-income tenants. This can be understood as a reduction in the financing costs of the housing developer. By reducing financing costs, the affordable housing developer can reduce rents to “affordable” rates.

The Low-Income Housing Tax Credit has decreased in value over recent years, possibly because investors have less interest in buying the credits from housing developers. Without investor demand for the tax credits, housing developers cannot effectively reduce costs. Finding new ways to either bolster LIHTC or find new funding sources is of key importance for policymakers.

Direct Capital Expenditures

The most intuitive tool that the State can use to fund new affordable housing development is investing directly in housing projects, i.e. devoting financial resources directly into building and maintaining affordable housing. These expenditures can be invested in new State-owned housing or can take the form of subsidies or grants to private developers.

To see how direct government spending on housing development could work, imagine the State were to allocate $5 billion in capital towards new affordable housing developments. If the State chooses not to borrow additional funds, $5 billion in capital expenditures can build between 10,000 and 20,000 units of housing at current costs (each unit costs between $250,000 and $500,000 to build). Once construction is finished, the State would have to fund ongoing operations and building maintenance. Depending on the rents charged to tenants, the State may need to supplement rental payments with ongoing operating funds. If the housing is kept in good condition and used for mixed-income housing, rather than 100 percent affordable housing, then it is possible for the State to operate the housing without operating subsidies, or even possibly at a profit, yielding additional revenue that could be used to continue expanding housing development.

In the case described above, the State is acting as the primary funder and owner of the housing development. However, the State can also give grants and subsidies to owners and developers of housing without taking an ownership stake itself. There are many examples of such government expenditures in New York. For example, New York City’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) gives grants directly to non-profit developers of low-income housing that are either constructing or developing new housing in the City. By delivering grants to developers, the city directly decreases the developers’ needs for debt financing and thus reduces the monthly debt repayment fee paid by the developer. By reducing financing costs, the housing development can increase affordability of housing units created.

Tax-Exempt and Taxable Bonds

The State can also borrow funds, typically by issuing either taxable or tax-exempt bonds. These bonds are issued by the State, bought by private bond investors, and paid back over time through tax revenue. In the case of tax-exempt bonds, the investor’s interest on the bond is tax-exempt, allowing the State to offer the bond at a lower interest rate, and thus reducing the State’s overall costs. Again, by reducing costs, the State can build more affordable housing units.

Imagine the State were to issue $20 billion in bonds, to be sold to investors and paid back over time. At current construction prices in New York, $20 billion in capital funds could build between 40,000 and 80,000 homes (assuming each unit costs between $250,000 and $500,000 to build). The State would then need to pay back the $20 billion borrowed plus the coupon rate — i.e. the interest rate — on the bond using either tax revenue or rental revenue. Unless there is a tax-funded revenue stream, these debt repayments would weaken the State’s ability to offer the units at affordable rents, demonstrating the affordability-financing trade off discussed previously. However, to the extent that the State can drive down construction, land-acquisition and financing costs, these housing developments may be able to attain more affordability than typical market-rate housing. Certainly, the tax-exempt nature of the bond financing in many cases decreases the interest rate on the bond and reduces the overall cost burden of the financing.

The State can and does also deploy tax-exempt bond financing to support low-cost lending to private housing developers. This will be discussed further in the next section.

Government lending to private developers: The Montgomery County Model

Another tool that can be used by the government to promote housing construction is a government lending facility that offers low-cost financing to housing developers. Because the government can loan funds at relatively low interest rates, the government can reduce the cost of financing for affordable housing developers. This is particularly important when high interest rates are making financing challenging for developers, as has been the case in recent years.

Montgomery County, Maryland has received recognition recently for its creation of a revolving loan fund to help finance new multi-family housing with affordable units. It is projected that by efficiently deploying the capital raised by a $100 million municipal bond issuance, Montgomery County will be able to build 1,500 units of new housing every five years on a continual basis. With a small return on the loans they provide to developers, the total cost to the county of building this new mixed-income housing is only $2.7 million annually. Here’s how this works:

- First, Montgomery County issues $100 million in bonds. The bonds are sold on the municipal bond market, and the bondholders are entitled to interest payments that costs the County $7.7 million each year for 20 years;

- The County uses the $100 million that it received from the sale of the bond as financing for private developers that need cash during the construction process. This eliminates the need for a construction loan, which can be more expensive on the private market. By borrowing from the government instead, the private developer reduces the cost of construction, and thus the long-term financing costs of the project;

- Once the construction process is complete and the buildings are leased-up, the private developer fully pays back the loan principle to the County, plus five percent interest (five percent interest on $100 million is $5 million). At this stage, the County has recovered the original $100 million, plus interest income of $5 million per year, and owes bond investors $7.7 million per year. On net, the County government then needs to raise another $2.7 million per year to pay its bond investors.

This process creates about 1,500 units of housing every five years at a cost of $13.5 million to taxpayers. Montgomery County also uses a mixed-income model to cross-subsidize for affordability. A typical project rents 70 percent of its units at the market rental rate, and rents out the remaining 30 percent of units to be affordable to families earning below 80 percent of the area median income. With this income mix, the overall public cost is $30,000 for each permanently affordable unit and no cost for the market-rate units.

Once a project has been leased up and the $100 million loan repaid, the County can repeat the construction process, creating more housing units with the same initial loan fund and low cost to taxpayers. After twenty years, the bond investors will be paid off and the County will be operating at a profit, allowing either more units or deeper affordability levels.

Ultimately, by reducing the cost of financing for the housing development, the County is ensuring that the housing can sustain some level of affordability for renters. Additionally, the County puts downward pressure on the cost of financing by competing with private lenders. This has the potential impact of reducing financing costs across the entire market.

At an investment of $100 million, the Montgomery County model can only feasibly support the building of a few hundred units per year (1,500 every five years). However, if financed at $1 billion, as could be achieved in New York, a revolving lending facility of this sort could support the construction of a few thousand units per year at very low long-term cost to New York taxpayers. The level of affordability that could be attained under this model depends on the rate of interest charged by the government relative to the rate of interest charged by private developers.

Tax Incentives

Tax incentives – also known as “tax expenditures” and “tax benefits” – have been widely used in recent history for many policy purposes including affordable housing, economic development, and efforts to move towards more renewable energy production. In the case of a tax expenditure, the state or federal government lowers the tax liabilities of entities that take on certain publicly desirable business activities. For example, the government may desire the production of more housing than is currently profitable. To stimulate additional building, the government would lower the tax liability of housing developers so that a greater amount of housing becomes profitable to build. In Figures 2-4, this corresponds to decreasing the size of the red/pink “Expenses” box, which increases the overall Net Operating Income and thus the profitability of the project. This makes it possible to create more affordable housing by lowering the cost of construction and building operating expenses.

As discussed above, the LIHTC is a federal tax credit policy intended to lower the cost of developing affordable rental housing. In New York City, the long-standing 421-a tax credit has been used to incentivize developers to build multi-family apartment buildings that have some income-restricted units and was recently renewed under the name Affordable Neighborhoods for New Yorkers (a.k.a. 485-x) in the fiscal year 2025 state budget. The fiscal year 2025 state budget also included an upstate tax incentive policy (421-p) and a tax credit for commercial conversion in New York City (467-m).

The 421-a tax credit (now replaced by 485-x) was originally put into place in the 1970s, at which point the intent of the policy was to promote the construction of market rate housing, with no required affordability requirements. Over time, the policy evolved to include affordability requirements for participating housing developments. In a 2022 report, the New York City Comptroller’s office found that foregone tax revenue amounted to between $1.7 billion and $1.8 billion each year between 2019 and 2022.[vii] The report found that over the years 2017-2020, a total of 14,874 housing units were built under 421-a, with only 4,456 of those units deemed “affordable.” Over 60 percent of all units deemed affordable were for families whose incomes were for families making 130 percent of the area median income (well over $100,000/year in annual income). The Comptroller’s office found that New York City foregoes over $60,000 annually for 35 years for each unit of affordable housing. For each unit that is affordable to those making less than 60 percent of the area median income, the city foregoes over $120,000 annually for 35 years. These expenses far exceed the expenses of both section 8 vouchers and NYCHA’s section 9 public housing. However, the program is also subsidizing new housing stock, rather than simply sustaining tenants in already-existing housing stock. Interpreting these costs in the context of the housing supply crisis in New York City is challenging and requires a deeper look into the cost of construction in the city.

For a state or locality that lacks enough tax revenue to directly spend on affordable housing development, a tax incentive might make sense; there isn’t tax revenue enough to spend directly, but offering a tax incentive might enable development that would not otherwise take place. Small municipalities and local governments often fall into this category because they lack sufficient funds to front-load their costs with cash that they have on hand or can reliably raise over a short time horizon. The tax incentive can attract private capital and developers to undertake a project that the government wants and otherwise would not be profitable.

However, tax incentives can easily result in waste if the development would have occurred even in the absence of the policy. Distributing tax incentives using a competitive process that ensures that the incentives will be used to create otherwise financially infeasible projects is essential to a successful policy. This mechanism is notably lacking in programs like 421-a that operate as-of-right, meaning that all eligible projects will receive the benefit, regardless of whether they need the benefit to be viable. Tax abatement also has the side effect of lowering the capacity of the government to build expertise, raise revenue, and undertake large scale capital projects.

Figure 5. Diagram illustrating the allocation of tax benefits to housing developers by project profitability.

Conclusion

By developing new financing tools and leveraging public assets, New York State can support the robust provision of affordable housing in the state. This is increasingly urgent as families leave in search of greater affordability. To increase housing affordability in the State, policymakers must develop plans to increase the provision of multi-family affordable housing. To do this requires an understanding of how housing developments are financed, what the major costs of development are, and what policy tools the State can use to alleviate costs.

The major costs of developing and operating new multifamily housing include land acquisition costs, construction costs (which includes construction materials, labor, and other soft costs), property taxes, financing costs (the cost of repaying any outside investment in the property), and ongoing operating costs (building maintenance, marketing, etc.). Investigating each of these costs can provide opportunities for state intervention to lower costs, thereby increasing the overall provision of housing and the potential for affordability.

Financing costs — i.e. the cost of borrowing funds to pay for the up-front costs of development — offer a key lever for the State to promote the provision of new multi-family housing and make affordable units more readily available across the state. By leveraging already-existing policy tools, such as Federal Housing Choice Vouchers and the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit, and developing new innovative approaches to limiting financing costs for housing development, as has been pioneered in places like Montgomery County, Maryland, New York State can promote multi-family housing development that includes affordability standards. Mitigating financing costs also has the long-term benefit of smoothing the cyclicality of housing construction in the State, which will play a large role in meeting the housing supply needs that are currently far from met.

[1] Median asking rent is distinct from the median observed rent. The median asking rent only considers housing units that are currently listed as “for rent,” whereas the median observed rent would include all units regardless of whether they are currently listed as available on the market.

[i] US Census Bureau, “Quick Facts,” https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/newyorkcitynewyork/HSG010222

[ii] StreetEasy Data Dashboard, https://streeteasy.com/blog/data-dashboard/?agg=Median&metric=Asking%20Rent&type=Rentals&bedrooms=Any%20Bedrooms&property=Any%20Property%20Type&minDate=2010-01-01&maxDate=2024-06-01&area=Flatiron,Brooklyn%20Heights

[iii] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers: Rent of Primary Residence in New York-Newark-Jersey City, NY-NJ-PA (CBSA) [CUURA101SEHA], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CUURA101SEHA, June 17, 2024.

[iv] https://www.buildingcongress.com/uploads/COU_-_NYC_Construction_Costs_v5_digital_distro.pdf

[v] The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, “Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD)” https://www.hud.gov/RAD

[ii] The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, “Tenant Protection Vouchers” https://www.hud.gov/program_offices/public_indian_housing/programs/hcv/tenant_protection_vouchers

[vii] “A Better Way Than 421-a: The High-Rising Costs of New York City’s Unaffordable Tax Exemption Program,” March 16, 2022. https://comptroller.nyc.gov/reports/a-better-way-than-421a/#_ftnref23