Inequality in New York & Options for Progressive Tax Reform

November 9, 2022 |

November 10, 2022

KEY FINDINGS:

- A new report from the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) finds that New York State is home to the highest concentration of extreme wealth in the United States. New York State also has the greatest income inequality in the United States.

- In order to understand inequality, we need to look at both income and wealth. By both of these measures, New York is the most unequal state in the nation.

- New Yorkers worth over $30 million collectively own $6.7 trillion in wealth. These ultra-rich New Yorkers are just 0.4 percent of the state population. These ultra-rich New Yorkers also hold about one fifth of the total wealth held by all ultra-rich Americans — the highest concentration of wealth in any state.

- Of the $6.7 trillion held by ultra-rich New Yorkers, ITEP estimates that $3.1 trillion consists of unrealized capital gains. Much of this wealth will never be taxed under current law.

NEW YORK STATE TAX POLICY IMPLICATIONS:

- New York’s current tax system, taken as a whole, is regressive: the wealthy pay about the same combined state and local tax rate as the bottom 40 percent.

- Because of the substantial overlap between high income earners and owners of extreme wealth, increasing the progressivity of the existing Personal Income Tax would help to address extreme inequality:

- The state should increase tax rates for the top brackets, and restore the $500,000 tax bracket from the post-financial crisis years; and

- At a minimum, the state should not allow the current PIT rates on high earners to expire, as they are currently set to, in 2027.

- Our state tax system can further address extreme inequality, and increase overall progressivity, with the following tax policy options:

- Increasing tax rates on long-term capital gains for high-income taxpayers;

- Taxing unrealized capital gains on a mark-to-market basis for wealthy taxpayers;

- Increasing taxes on business profits, such as those earned through pass-through entities such as LLCs, and targeting the profit-shifting of multinational corporations;

- Taxing inherited wealth, or fixing the estate tax by lowering the exemption threshold and eliminating step-up in basis; and

- Revising the state constitution to permit a direct wealth tax.

NEW YORK: THE HIGHEST INEQUALITY IN THE NATION

Income statistics have long shown that the top earners in New York State earn relatively more than their counterparts elsewhere in the U.S.[1] Income inequality alone, however, provides an incomplete picture of the wealthiest households’ economic resources. In order to understand real economic power, we have to look at households’ wealth (their total net assets). Wealth accumulates over generations, often escapes taxation, and enables the ultra-rich to make major expenditures and leverage capital. Wealth is also distributed very unevenly across racial groups. Nationally, white households hold 86 percent of all wealth and 92 percent of extreme wealth.

While measuring wealth inequality is difficult, research recently published by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) sheds new light on the geographic concentration of extreme wealth (defined as households with a net worth of $30 million or more). ITEP finds that, like income inequality, New York is home to the greatest concentration of extreme wealth in the country: the wealthiest New Yorkers together own $6.7 trillion in net assets, much of which will never be taxed under current law.[2] This brief provides a statistical overview of the state’s income and wealth inequality and discusses options for progressive taxation of the wealthiest New Yorkers.

New York has the highest income inequality in the U.S.

New York State has the highest level of income inequality in the U.S. In a 2018 study, the Economic Policy Institute found that the average income of the top 1 percent of earners in New York was over 44 times the average income of the bottom 99 percent — the most extreme disparity of any state. This ratio is driven by the stratospheric top incomes, which were concentrated in Manhattan. The borough’s top 1 percent earned an average of $8.98 million per year.[3] More recent Census data confirms this conclusion, estimating New York’s Gini coefficient — which gauges disparity across the income distribution — to be 0.514, the highest of any state.[4]

The World Inequality Database further highlights New York’s top 1 percent as a driver of income inequality. The nation’s second-highest earning group (behind Connecticut), New York’s top earners take in 60 percent more than their national counterparts. New York’s top 10 percent earn 35 percent more than their nationwide peers.

Figure 1. Average incomes in New York and U.S.

| New York | U.S. | |

|---|---|---|

| Top 1 percent | $2,447,358 | $1,532,189 |

| Top 10 percent | $470,063 | $348,453 |

| Bottom 90 percent | $39,316 | $32,928 |

Source: World Inequality Database. 2018 data expressed in 2021 dollars.

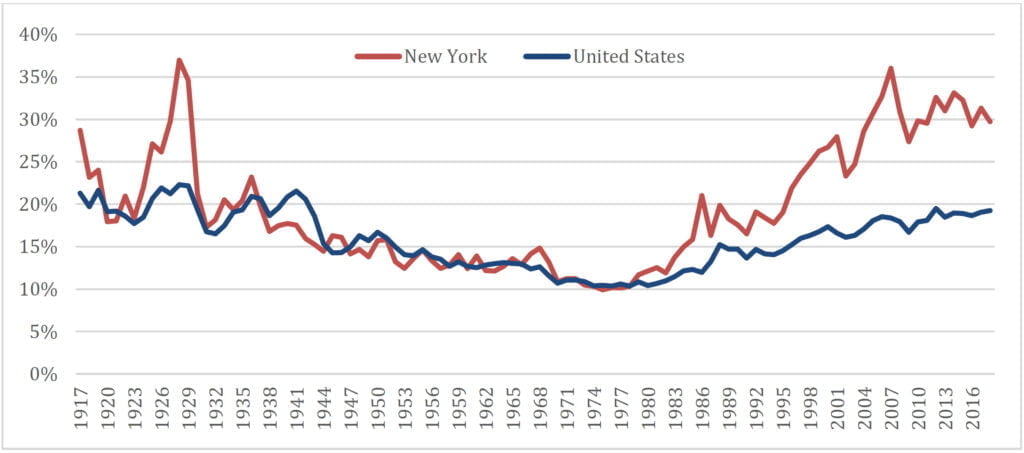

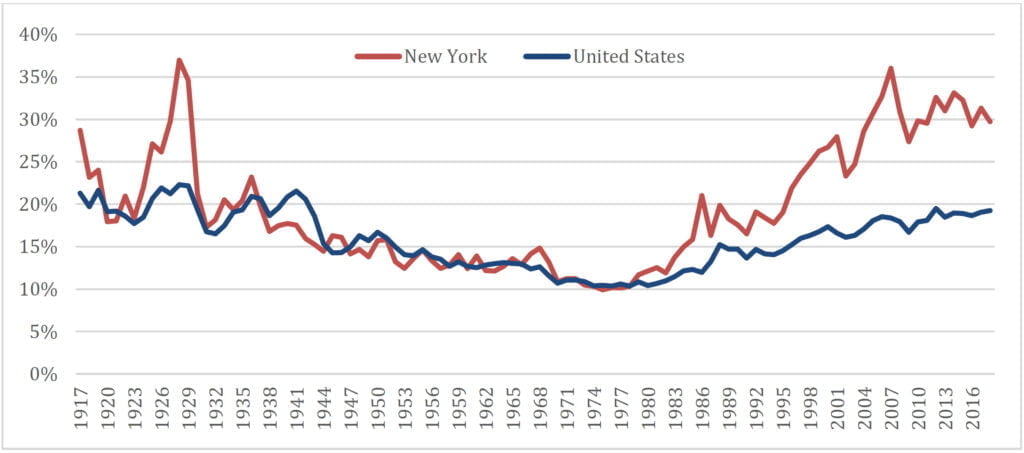

New York has not always been a bastion of income inequality. Through the late 1970s, the share of income taken in by New York’s top earners — hovering around 10 percent — was on par with the U.S. as a whole. While national income inequality began a steady, continuous ascent in the 1980s, New York’s top income share rose at a far faster pace. The Economic Policy Institute has found that between 1973 and 2015, the income share of New York’s top 1 percent tripled, rising 20.5 percentage points, the most of any state.[5] Since 2010, the top 1 percent income share has oscillated between 29 and 33 percent, levels not seen since the period leading up to the Great Depression and far higher than the national level.[6] Because New York’s top incomes are largely driven by the fortunes of the financial services industry, they exhibit more volatility than the national measure. Immediately prior to the 2008 financial crisis, the state’s top 1 percent of earners took in 36 percent of total income, nearly on par with 1928’s 37 percent.

Figure 2. Top 1 Percent Income Share in New York and the U.S., 1917 to 2018

Source: World Inequality Database

New York State has the highest concentration of extreme wealth in the U.S.

The share of income earned by the top 1 percent of earners provides important information about the structure of the labor market, illustrating the sharp economic divergence over recent decades between top earners in the New York City metropolitan area and the vast majority of workers in New York and nationally. As a measure of the wealthiest households’ total economic resources, however, measuring income is inadequate. Income statistics capture information on individuals’ wage income, business profits, rents, realized capital gains, and any other income within a given time period. By contrast, wealth includes assets that are not captured in individual income: inherited assets, unrealized capital gains (e.g., appreciated but unsold stock holdings or real estate), and lifetime savings. As such, wealth is a more complete measure of the distribution of a society’s economic resources.

Wealth is also generally distributed more unequally than income. While the top 1 percent of earners account for about 20 percent of national income, the wealthiest 1 percent hold about 35 percent of the nation’s wealth. This differential has been rising. Between 1978 and 2019, the average inflation-adjusted income of the top 1 percent of earners rose at an average annual rate of 2.8 percent. The average net worth of the wealthiest 1 percent rose 50 percent faster over the same period, at an average annual rate of 4.2 percent.[7]

Like income, wealth is geographically concentrated. Data on state-level wealth distribution is scarce, however, due to the methodological complexity of estimating the extreme concentration of wealth among top holders, who are too few to be covered by surveys. A recent ITEP report aims to redress this gap. Using a novel methodology drawing from tax and survey data as well as data compiled by Forbes on billionaires’ assets, ITEP maps the distribution of extreme wealth across U.S. states.[8]

The data reveal a striking concurrence of the geographic concentrations of top incomes and extreme wealth. New York, which hosts the nation’s highest level of income inequality, is also home to its greatest concentration of extreme wealth. ITEP estimates that households in the U.S. that are worth over $30 million (whom we will call the “ultra-rich”) collectively hold $38.9 trillion in wealth. Of this, the ultra-rich in New York State collectively hold $6.7 trillion in wealth, or about one-fifth of all wealth owned by the ultra-rich in the U.S. This makes New York State home to the most extreme wealth on both an absolute basis and in relation to its total population.

The subset of 78 billionaire households in New York hold $673 billion in wealth. This places New York second in the nation in billionaire wealth, after California (where billionaires hold $945 billion). California’s population of 39 million, however, is about twice that of New York’s (20 million). This concentration of wealth is largely due to New York’s financial industry.[9]

ITEP further estimates the unrealized capital gains held by both the ultra-rich as well as the subset of billionaires. Of the $6.7 trillion held by New York’s ultra-rich, $3.1 trillion is in unrealized capital gains (appreciated stock, real estate, or other assets that have not been sold). New York’s billionaires hold $470 billion of their $673 billion in unrealized capital gains. A significant part of these unrealized gains will not be taxed under current law, due to the step up in basis rules, which eliminate taxable gain when assets are passed on to one’s heirs at death, and because the ultra-rich often contribute their holdings to private foundations.

State-level IRS data reinforce this finding. Tax data released every few years by the IRS report total assets held by households with more than $5.45 million in wealth. The most recent dataset finds that New York is home to the third highest level of top wealth holder net assets, behind California and Florida.[10]

Most analyses underestimate extreme wealth in New York State

That New York is home to such concentrations of extreme wealth is remarkable, as survey-based measures of wealth do not show the state to be especially wealthy. According to recent U.S. Census data, New York’s median household wealth was $144,500, nearly on par with the national median of $140,800 and the 25th highest in the U.S. The same data shows the state’s average household wealth — which skews upwards as a result of concentration at the top of the distribution — to be $524,400, the 18th highest in the country.[11] Because wealth is so heavily concentrated in the hands of a few households, survey samples generally fail to adequately capture top households, undercounting extreme wealth. Tax data reported by the IRS and ITEP data, which is supplemented by tax data and Forbes data on billionaire wealth, aim to redress this undercount. In so doing, both find that rather than hosting a nationally-average amount of wealth, New York is home to a vast pool of extreme wealth.[12]

| Number of New York Tax Filers | Share of New York Tax Filers | |

|---|---|---|

| $5.45 million or more (IRS data) | 56,200 | 0.79 percent |

| Over $30 million (ITEP estimate) | 28,300 | 0.40 percent |

| Over $100 million (ITEP estimate) | 15,300 | 0.22 percent |

| Over $1 billion (ITEP estimate) | 78 | 0.0011 percent |

Sources: IRS; FPI analysis of ITEP and NYS Department of Taxation and Finance data

IRS and ITEP estimates of the top wealth holders’ collective assets are not measures of inequality, and state-level data on the entire wealth distribution remains lacking. Survey-based wealth data differ from one another in estimates of total and average wealth. Because the ITEP dataset is designed specifically to measure extreme wealth, it begins with survey data that better counts wealthy households and supplements it with Forbes data on billionaire wealth. Because Census data on median wealth undercounts top wealth it cannot be compared directly against either ITEP or IRS findings. Nevertheless, these measures are clear and important signals of the economic trajectories of the most affluent households. For New York, the data clearly chart the rise of an extraordinary concentration of wealth at the top of the distribution amid relatively average holdings by the vast majority. Further, estimates of extreme wealth have significant bearing on the policy choices and design of an effective progressive tax system.

OPTIONS FOR PROGRESSIVE TAX REFORM

These statistics point to two key policy recommendations for New York State. First, we should focus on increasing the overall progressivity of our state’s existing tax laws. Second, we should consider new reforms and instruments that would specifically target extreme wealth.[13]

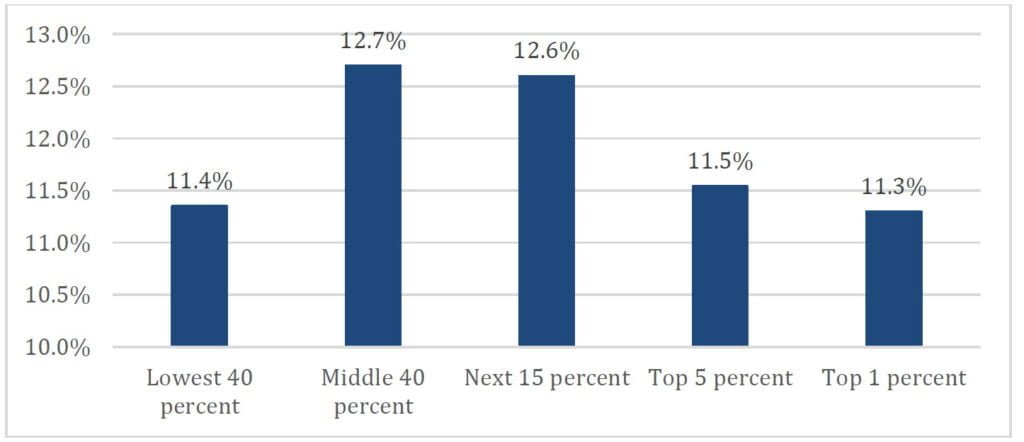

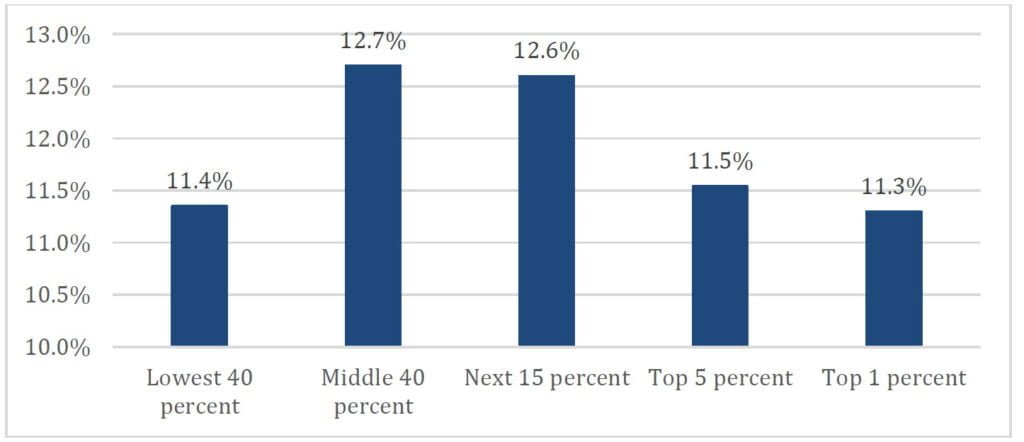

Taken as a whole, New York’s tax system is regressive: the wealthy pay a lower combined state and local tax rate than those in middle income brackets, and about the same combined state and local tax rate as the poor. The state’s personal income tax (PIT) is the only progressive component of the state’s tax system, imposing higher rates on higher income earners. Sales taxes, which are levied at the state and local level, and property taxes, assessed only at the local level, are regressive, taking a larger share of income from the lowest income households. A 2019 ITEP report finds that taken together, these three taxes — income tax, sales tax, and property tax — are effectively flat across the income distribution. The bottom 40 percent of households and the top 1 percent of households pay nearly the same state and local tax rates of just over 11 percent, while the middle 55 percent pay a rate of 12.5 to 13 percent.[14]

Figure 4. New York State and Local Tax as Share of Family Incomes?

Source: ITEP

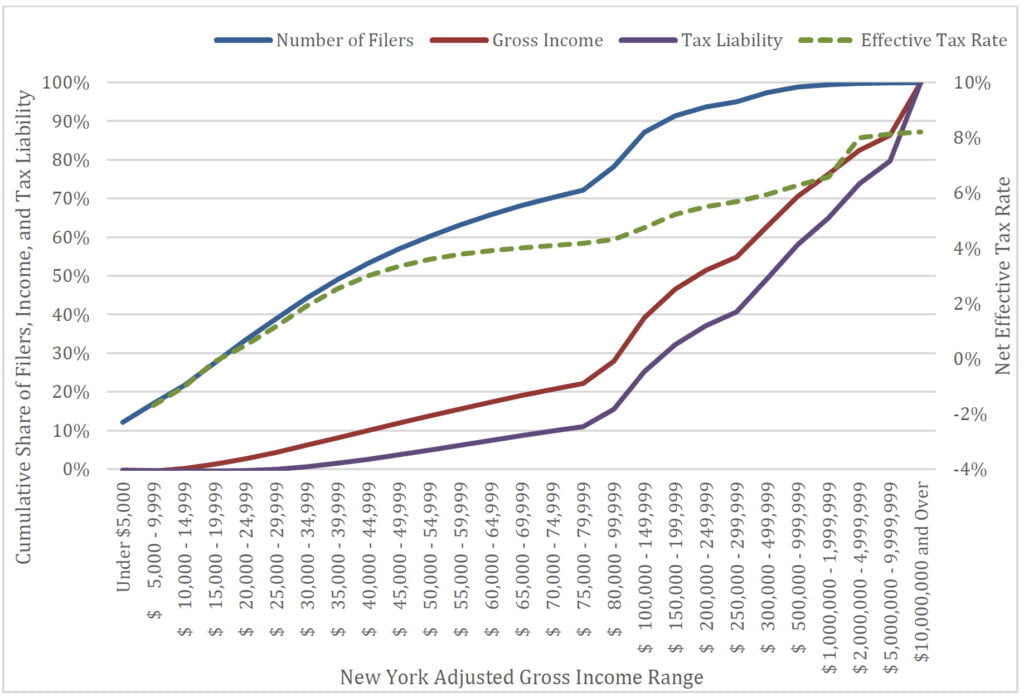

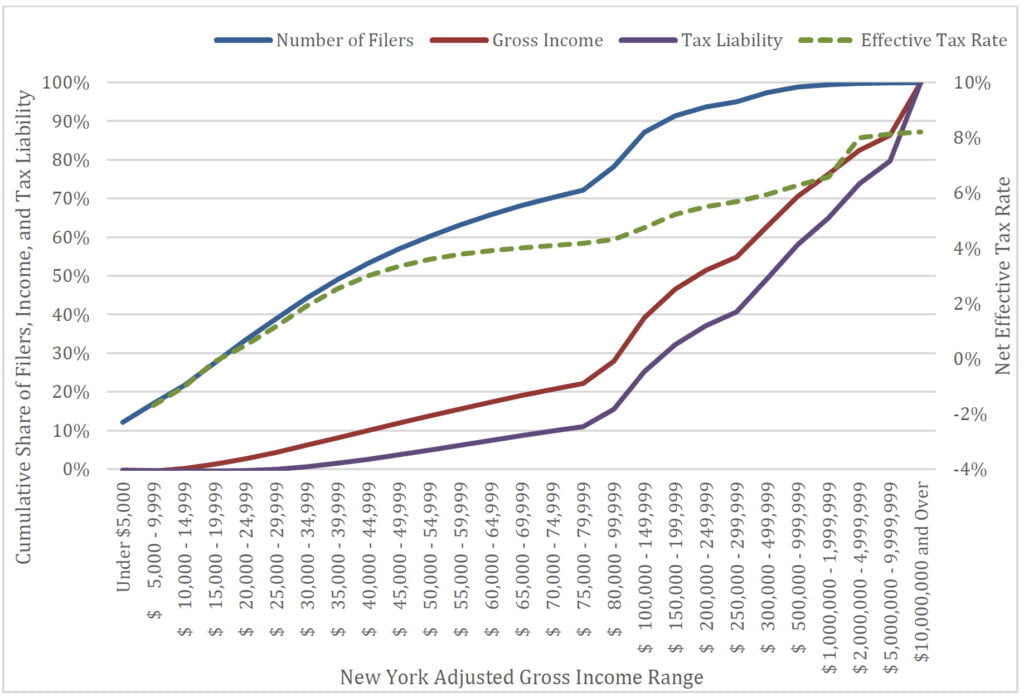

New York State’s tax system is highly reliant on the PIT. In fiscal year 2022, PIT receipts accounted for 58.4 percent of all state tax revenue. In turn, PIT revenue is highly dependent on the highest income New York tax filers. This is a result of New York’s extreme income inequality as well as its progressive PIT rates. In tax year 2020, the most recent available, 128,700 tax filers reported New York gross adjusted income above $1 million, 1.2 percent of all tax filers. These filers collectively paid 41.9 percent of all PIT liability.[15] The state’s PIT rates are modestly progressive across the income distribution as a result of recent policy changes. However, income as the sole basis for progressive taxation overlooks the far more unequally-distributed resources available to the wealthiest New Yorkers.

The findings discussed in this brief reveal enormous reserves of wealth in New York held not just by a few billionaires, but a class of top wealth holders whose numbers rival the state’s top earners. While the two groups may not neatly overlap, recent evidence suggests that top wage earnings and wealth holdings increasingly belong to the same households in the U.S.[16] Taken together, these households represent a core element of the state’s tax base. A tax system that accounts for the extreme wealth concentrated at the top of the distribution would raise more revenue from top wealth holders than a PIT that appears progressive only against the benchmark of the relatively more egalitarian income distribution.

Figure 5. New York Cumulative Income and Tax Liability, 2020

Source: NYS Department of Taxation and Finance

Moving toward such a tax system does not imply a single set of tax policies. Rather the options that the state might pursue depend on the policies’ legal status, administrative complexity, and fiscal and economic conditions. In some cases, complementary policies, or policies designed to expand over time, may be appropriate. This paper provides an overview of tax policy options that would increase revenue, increase progressivity, and reduce inequality in New York State. It covers seven options over three major areas of taxation: income taxes, business taxes, and wealth taxes.

1. Increase the Progressivity of the Personal Income Tax

Prior to the 2008 financial crisis, New York’s PIT was flat for all income earned above $40,000.[17] To fill budget gaps created by the ensuing recession, lawmakers created two higher tax brackets on income above $300,000 and $500,000. As the state’s fiscal condition improved, PIT rates were lowered for upper-middle class tax filers earning less than $1 million. The fiscal crisis that followed the Covid pandemic created a new impetus for progressive taxation. Lawmakers raised taxes on incomes over $1 million per year and created two new brackets for those earning $5 million and $25 million per year.

Figure 6. Top New York State PIT Rates in Years Following Major Changes

Source: NYS Department of Taxation and Finance; rates shown for married, joint filers

Because income and wealth are closely correlated, a progressive PIT is an effective and easily implemented tool to raise revenue from holders of extreme wealth. Lawmakers can quickly adjust PIT rates in response to fiscal conditions and target top incomes at a granular level. The recently enacted top PIT rate increases represent the first time the state’s rates began to account for the lopsided concentration of resources held at the top of the income and wealth distributions.

At a minimum, data on extreme wealth suggest that the state should not allow the new PIT rates to expire, as they are currently set to, in 2027. Further, the state should increase the rates for the “millionaire” brackets (for about $1 million, $5 million, and $25 million in annual income), and restore the $500,000 tax bracket from the post-financial crisis years.

2. Raise the Tax Rate on Long-Term Capital Gains

Capital gain is profit from the sale of assets such as stocks and bonds, real estate, intellectual property, or artwork. New York taxes capital gains at the same rates as all other income from other sources. The federal tax code, however, provides a significant tax break for long-term capital gains. While the top federal tax rate on individual income is 37 percent (and was 39.6 percent prior to the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act), the top federal tax rate on long-term capital gains is just 20 percent.[18] Numerous policymakers have long opposed this provision, which overwhelmingly benefits the rich, but the federal government has failed to remedy the problem.[19] According to the Tax Policy Center, in 2019 over 75 percent of all long-term capital gains went to the top 1 percent of earners, and only 6 percent of all long-term capital gains went to the bottom 80 percent of earners.[20] By raising tax rates on long-term capital gains for high earners, the tax system would better target extreme inequality.

3. Tax Capital Gains on a Mark-to-Market Basis

Importantly, our current tax system only taxes capital gains when the underlying asset is actually sold (for instance, when an individual sells appreciated stock). In tax parlance, this is called “realizing” the gain. This system leaves vast sums of unrealized capital gains on the table. ITEP estimates that New Yorkers with more than $30 million in assets collectively hold more than $3 trillion in unrealized capital gains — 46 percent of their total wealth. Much of this wealth will not be taxed under current law, largely due to the step up in basis rules that eliminate taxable gain when assets are passed on to one’s heirs at death. Moreover, wealthy families often borrow against accumulated assets in order to finance their lifestyles, while avoiding the tax consequences of a sale. Finally, wealthy individuals often contribute their appreciated assets to private foundations run by their own family members, avoiding tax on their gains while keeping their assets in the family for all practical purposes.

A “mark-to-market” income tax system would tax asset appreciation as it occurs, rather than waiting for the taxpayer to realize their gains. For instance, if a wealthy individual’s investment portfolio grows in value by $10 million over the course of a year, they would be treated as earning $10 million of taxable income in that year.[21]

Implementing a comprehensive mark-to-market income tax on ultra-rich taxpayers would require annual valuations of all assets in order to measure the annual gains. Critics commonly hold that this is practically impossible or else unreasonably burdensome, but tax law scholars have shown how the challenge could be met.[22] Additionally, mark-to-market rules could be applied to all of a taxpayer’s historical unrealized gains, or imposed only on a prospective basis. The former option would immediately raise windfall revenue before falling to a baseline annual revenue. A more incremental option would be to only tax current year capital gains on a mark-to-market basis, thereby foregoing the initial windfall revenue. The scope of the tax could be further limited to publicly traded instruments, so as to avoid the challenges of valuing private assets.

4. Tax the Profits of Pass-Through Businesses

The wealth of the ultra-rich generally takes the form of business holdings, whether through privately or publicly owned corporations, or through “pass-through” businesses such as partnerships and LLCs. Taxing business profits is thus an important policy tool for both reducing inequality and raising revenue. While many people think of all businesses as “corporations,” the corporation is in fact only one type of business entity. Most businesses are now formed as LLCs or partnerships, which are called “pass-through entities” because they are not subject to the corporate tax — rather, the profits are only taxed at the level of the individual owners.[23]

A starting point for taxing pass-through entities is New York’s Pass-Through Entity Tax (PTET). Currently, this tax is 100 percent rebated, bringing in no additional revenue. The tax is not designed to raise revenue, but rather to work around the federal limitation of the state and local tax deduction, and it overwhelmingly benefits the wealthy. According to ITEP, 85 percent of the benefit of the state and local tax deduction in New York State goes to the top 5 percent of income earners.[24] Because these taxpayers will still benefit from electing to pay the PTET even without a full rebate, New York should only rebate part of the tax. For instance, Connecticut rebates only 87.5 percent of its Pass-Through Entity Tax.[25]

5. Tax the Profit-Shifting of Multinational Corporations

New York should increase the amount of global intangible low-taxed income (GILTI) includible in the state corporate tax. GILTI is a provision of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act that targets the profit-shifting of multinational corporations by taxing unusually high profits in overseas jurisdictions. It is generally thought that such high profits result from shifting valuable intellectual property into foreign low-tax jurisdictions.[26]

6. Reform the Estate Tax, or Tax Inherited Income

In principle, the estate tax should function as a tax on accumulated wealth at the end of an individual’s life. However, it has largely ceased to perform this role due to a few unfortunate features of current estate tax law. Chief among them are that (i) the step up in basis rules eliminate taxable gain upon death, (ii) the estate tax exemption has continued to rise (currently, the first $26 million of an estate is exempt from federal estate tax), (iii) the wealthy can contribute their assets to a private foundation, thereby avoiding estate tax, and (iv) the estate tax planning industry has developed sophisticated tax avoidance techniques.

New York could reform any of the above features of its estate tax in order to more effectively tax accumulated wealth at death. Or, it could shift to a new, simpler inheritance tax scheme whereby inherited income is included in the recipient’s income, putting it on par with wage income and investment income.[27]

7. Enable a Direct Wealth Tax

Finally, New York could seek to impose an annual tax on the total wealth of the ultra-rich. ITEP estimates potential revenue from wealth taxes on holdings above $30 million and $1 billion at annual rates of 2, 3, and 4 percent. For New York, a 3 percent tax on wealth held above $30 million would raise $134.4 billion, greater than the entire New York State operating budget in fiscal year 2023. The same rate on wealth held above $1 billion would raise $13.2 billion.

Because a wealth tax would likely incentivize top holders to adopt tax avoidance strategies, a lower rate applied to a broader base would perform better than a higher rate on a narrower base. For New York, nearly $6 trillion of wealth is held by ultra-rich households that are not billionaires. Given that this group contains nearly 30 thousand households—rather than 78 billionaires—it makes for a sounder base for a potential wealth tax.

A state level wealth tax does face one considerable obstacles to implementation. The New York State Constitution prohibits a direct wealth tax, so a constitutional amendment would be necessary.

By Nathan Gusdorf and Andrew Perry

Nathan Gusdorf is the Executive Director and Andrew Perry is the Senior Policy Analyst at the Fiscal Policy Institute

[1] World Inequality Database, “Data: pre-tax income by U.S. state” (accessed October 2022), wid.world/data/.

[2] Carl Davis, Emma Sifre, and Spandan Marasini, “The Geographic Distribution of Extreme Wealth in the U.S.,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (October 2022), itep.org/the-geographic-distribution-of-extreme-wealth-in-the-u-s/.

[3] Estelle Sommeiller and Mark Price, “The new gilded age: Income inequality in the U.S. by state, metropolitan area, and country,” Economic Policy Institute (July 2018), epi.org/publication/the-new-gilded-age-income-inequality-in-the-u-s-by-state-metropolitan-area-and-county/.

[4] U.S. Census Bureau, “American Community Survey 2021 1-year file, Table B19083” (accessed October 2022), data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=B19083%3A%20GINI%20INDEX%20OF%20INCOME%20INEQUALITY. The District of Columbia has a higher Gini coefficient than any state.

[5] Estelle Sommeiller and Mark Price, “The new gilded age: Income inequality in the U.S. by state, metropolitan area, and country,” Economic Policy Institute (July 2018), epi.org/publication/the-new-gilded-age-income-inequality-in-the-u-s-by-state-metropolitan-area-and-county/.

[6] World Inequality Database, “Data: pre-tax income by U.S. state” (accessed October 2022), wid.world/data/.

[7] Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman, “The Rise of Income and Wealth Inequality in America: Evidence from Distributional Macroeconomic Accounts,” Journal of Economic Perspectives (Fall 2020), gabriel-zucman.eu/files/SaezZucman2020JEP.pdf.

[8] Carl Davis, Emma Sifre, and Spandan Marasini, “The Geographic Distribution of Extreme Wealth in the U.S.,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (October 2022), itep.org/the-geographic-distribution-of-extreme-wealth-in-the-u-s/.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Internal Revenue Service, “SOI Tax Stats-Top Wealthholders by State of Residence 2016” (accessed October 2022), irs.gov/statistics/soi-tax-stats-top-wealthholders-by-state-of-residence.

[11] U.S. Census Bureau, “State-Level Wealth, Asset Ownership, & Debt of Households: Detailed Tables: 2020” (accessed October 2022), census.gov/data/tables/2020/demo/wealth/state-wealth-asset-ownership.html.

[12] Census wealth data is collected by the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP). The primary purpose of the SIPP is to provide information on low-income households’ asset portfolios and use of public assistance programs. For this reason, the SIPP oversamples low-income households. By contrast, ITEP estimates are based on the Survey of Consumer Finance (SCF), which oversamples high-income households. ITEP further supplements their estimates of extreme wealth with two additional sources of data. First, ITEP uses regression analysis to generate a set of correlates between wealth data, which is available at the national level from the SCF, and IRS income data, available at the state level. These correlates produce estimates of asset ownership with the IRS income data. Because this data still fails to capture wealth at the extreme top of the distribution, ITEP further supplements their estimates with journalistic data on billionaire asset holdings compiled by Forbes. This novel methodology provides a set of estimates able to capture extreme wealth at the state level.

For a discussion of SIPP and SCF data, see Jonathan Eggleston and Mark Klee, “Reassessing Wealth Data Quality in the Survey of Income and Program Participation,” U.S. Census Bureau (February 2015), census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/working-papers/2016/demo/SEHSD-WP2016-17.pdf.

[13] A progressive tax system imposes a greater burden on those with a greater ability to pay. Both the U.S. federal income tax and the New York personal income tax impose higher tax rates on individual taxpayers with higher incomes, although the U.S. federal income tax is more progressive overall.

[14] Meg Wiehle et al. “Who Pays? A Distributional Analysis of the Tax Systems in all 50 States: Sixth Edition” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (October 2018), itep.org/whopays/.

[15] New York State Department of Taxation and Finance, “Personal Income Tax Filers, Summary Dataset 3 – Statewide Major Items and Income & Deduction Components by Liability Status and Detail Income Range: Beginning Tax Year 2015” (accessed October 2022), data.ny.gov/Government-Finance/Personal-Income-Tax-Filers-Summary-Dataset-3-State/rt8x-r6c8.

[16] Yonatan Berman and Branko Milanovic, Homoploutia: Top Labor and Capital Incomes in the United States, 1950-2020, World Inequality Lab (December 2020), wid.world/document/homoploutia-top-labor-and-capital-incomes-in-the-united-states-1950-2020-world-inequality-lab-wp-2020-27/.

[17] All rates are for joint return filers. New York State Department of Taxation and Finance, “2020 personal income tax forms: IT-201-I” and past editions (accessed October 2022), tax.ny.gov/forms/prvforms/income_tax_2020.htm.

[18] There is an additional 3.8 percent net investment income tax imposed on long-term capital gains for high-earning taxpayers as part of the Affordable Care Act.

[19] See, e.g., Galen Hendricks and Seth Hanlon, “Capital Gains Tax Preference Should Be Ended, Not Expanded” Center for American Progress (Sept. 28, 2020), americanprogress.org/article/capital-gains-tax-preference-ended-not-expanded/; Leonard Burman, “President Obama Targets the ‘Angel of Death’ Capital Gains Tax Loophole” Tax Policy Center (Jan. 18, 2015) taxpolicycenter.org/taxvox/president-obama-targets-angel-death-capital-gains-tax-loophole; William Gale and Leonard Burman, “The Case Against the Capital Gains Tax Cuts” (Sept. 1, 1997) Brookings Institute brookings.edu/opinions/the-case-against-the-capital-gains-tax-cuts.

[20] Distribution of Long-Term Capital Gains and Qualified Dividends, Tax Policy Center, taxpolicycenter.org/model-estimates/distribution-individual-income-tax-long-term-capital-gains-and-qualified-44.

[21] For years in which the individual’s portfolio loses value overall, such losses could be carried into prior or future years to offset gains, thus achieving fair tax treatment of their real economic income over time.

[22] Brian Galle, David Gamage, Darien Shanske, “Solving the Valuation Challenge: The ULTRA Method for Taxing Extreme Wealth”, Duke Law Journal (forthcoming), available at papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4036716.

[23] As of 2014, 95 percent of businesses were organized as pass-through entities. Aaron Krupkin and Adam Looney, “9 facts about pass-through businesses” Brookings Institute (May 15, 2017) brookings.edu/research/9-facts-about-pass-through-businesses.

[24] A Fair Way to Limit Tax Deductions” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, (Nov. 14, 2018) itep.org/a-fair-way-to-limit-tax-deductions/.

[25] “Pass-Through Entity Tax”, Connecticut State Department of Revenue (accessed November 2022), portal.ct.gov/DRS/Businesses/New-Business-Portal/Managing-PE-Tax.

[26] For a longer discussion of the argument for taxing GILTI, see Darien Shanske and David Gamage, “Why States Should Tax the GILTI” 91 State Tax Notes 751 (2019), available at papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3374987.

[27] For an extended analysis of the benefits and mechanics of an inheritance tax, see Lily L. Batchelder, “Leveling the Playing Field between Inherited Income and Income from Work through an Inheritance Tax”, NYU Law and Economics Research Paper Series (February 2020), available at papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3526520.

Inequality in New York & Options for Progressive Tax Reform

November 9, 2022 |

November 10, 2022

KEY FINDINGS:

- A new report from the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) finds that New York State is home to the highest concentration of extreme wealth in the United States. New York State also has the greatest income inequality in the United States.

- In order to understand inequality, we need to look at both income and wealth. By both of these measures, New York is the most unequal state in the nation.

- New Yorkers worth over $30 million collectively own $6.7 trillion in wealth. These ultra-rich New Yorkers are just 0.4 percent of the state population. These ultra-rich New Yorkers also hold about one fifth of the total wealth held by all ultra-rich Americans — the highest concentration of wealth in any state.

- Of the $6.7 trillion held by ultra-rich New Yorkers, ITEP estimates that $3.1 trillion consists of unrealized capital gains. Much of this wealth will never be taxed under current law.

NEW YORK STATE TAX POLICY IMPLICATIONS:

- New York’s current tax system, taken as a whole, is regressive: the wealthy pay about the same combined state and local tax rate as the bottom 40 percent.

- Because of the substantial overlap between high income earners and owners of extreme wealth, increasing the progressivity of the existing Personal Income Tax would help to address extreme inequality:

- The state should increase tax rates for the top brackets, and restore the $500,000 tax bracket from the post-financial crisis years; and

- At a minimum, the state should not allow the current PIT rates on high earners to expire, as they are currently set to, in 2027.

- Our state tax system can further address extreme inequality, and increase overall progressivity, with the following tax policy options:

- Increasing tax rates on long-term capital gains for high-income taxpayers;

- Taxing unrealized capital gains on a mark-to-market basis for wealthy taxpayers;

- Increasing taxes on business profits, such as those earned through pass-through entities such as LLCs, and targeting the profit-shifting of multinational corporations;

- Taxing inherited wealth, or fixing the estate tax by lowering the exemption threshold and eliminating step-up in basis; and

- Revising the state constitution to permit a direct wealth tax.

NEW YORK: THE HIGHEST INEQUALITY IN THE NATION

Income statistics have long shown that the top earners in New York State earn relatively more than their counterparts elsewhere in the U.S.[1] Income inequality alone, however, provides an incomplete picture of the wealthiest households’ economic resources. In order to understand real economic power, we have to look at households’ wealth (their total net assets). Wealth accumulates over generations, often escapes taxation, and enables the ultra-rich to make major expenditures and leverage capital. Wealth is also distributed very unevenly across racial groups. Nationally, white households hold 86 percent of all wealth and 92 percent of extreme wealth.

While measuring wealth inequality is difficult, research recently published by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) sheds new light on the geographic concentration of extreme wealth (defined as households with a net worth of $30 million or more). ITEP finds that, like income inequality, New York is home to the greatest concentration of extreme wealth in the country: the wealthiest New Yorkers together own $6.7 trillion in net assets, much of which will never be taxed under current law.[2] This brief provides a statistical overview of the state’s income and wealth inequality and discusses options for progressive taxation of the wealthiest New Yorkers.

New York has the highest income inequality in the U.S.

New York State has the highest level of income inequality in the U.S. In a 2018 study, the Economic Policy Institute found that the average income of the top 1 percent of earners in New York was over 44 times the average income of the bottom 99 percent — the most extreme disparity of any state. This ratio is driven by the stratospheric top incomes, which were concentrated in Manhattan. The borough’s top 1 percent earned an average of $8.98 million per year.[3] More recent Census data confirms this conclusion, estimating New York’s Gini coefficient — which gauges disparity across the income distribution — to be 0.514, the highest of any state.[4]

The World Inequality Database further highlights New York’s top 1 percent as a driver of income inequality. The nation’s second-highest earning group (behind Connecticut), New York’s top earners take in 60 percent more than their national counterparts. New York’s top 10 percent earn 35 percent more than their nationwide peers.

Figure 1. Average incomes in New York and U.S.

| New York | U.S. | |

|---|---|---|

| Top 1 percent | $2,447,358 | $1,532,189 |

| Top 10 percent | $470,063 | $348,453 |

| Bottom 90 percent | $39,316 | $32,928 |

Source: World Inequality Database. 2018 data expressed in 2021 dollars.

New York has not always been a bastion of income inequality. Through the late 1970s, the share of income taken in by New York’s top earners — hovering around 10 percent — was on par with the U.S. as a whole. While national income inequality began a steady, continuous ascent in the 1980s, New York’s top income share rose at a far faster pace. The Economic Policy Institute has found that between 1973 and 2015, the income share of New York’s top 1 percent tripled, rising 20.5 percentage points, the most of any state.[5] Since 2010, the top 1 percent income share has oscillated between 29 and 33 percent, levels not seen since the period leading up to the Great Depression and far higher than the national level.[6] Because New York’s top incomes are largely driven by the fortunes of the financial services industry, they exhibit more volatility than the national measure. Immediately prior to the 2008 financial crisis, the state’s top 1 percent of earners took in 36 percent of total income, nearly on par with 1928’s 37 percent.

Figure 2. Top 1 Percent Income Share in New York and the U.S., 1917 to 2018

Source: World Inequality Database

New York State has the highest concentration of extreme wealth in the U.S.

The share of income earned by the top 1 percent of earners provides important information about the structure of the labor market, illustrating the sharp economic divergence over recent decades between top earners in the New York City metropolitan area and the vast majority of workers in New York and nationally. As a measure of the wealthiest households’ total economic resources, however, measuring income is inadequate. Income statistics capture information on individuals’ wage income, business profits, rents, realized capital gains, and any other income within a given time period. By contrast, wealth includes assets that are not captured in individual income: inherited assets, unrealized capital gains (e.g., appreciated but unsold stock holdings or real estate), and lifetime savings. As such, wealth is a more complete measure of the distribution of a society’s economic resources.

Wealth is also generally distributed more unequally than income. While the top 1 percent of earners account for about 20 percent of national income, the wealthiest 1 percent hold about 35 percent of the nation’s wealth. This differential has been rising. Between 1978 and 2019, the average inflation-adjusted income of the top 1 percent of earners rose at an average annual rate of 2.8 percent. The average net worth of the wealthiest 1 percent rose 50 percent faster over the same period, at an average annual rate of 4.2 percent.[7]

Like income, wealth is geographically concentrated. Data on state-level wealth distribution is scarce, however, due to the methodological complexity of estimating the extreme concentration of wealth among top holders, who are too few to be covered by surveys. A recent ITEP report aims to redress this gap. Using a novel methodology drawing from tax and survey data as well as data compiled by Forbes on billionaires’ assets, ITEP maps the distribution of extreme wealth across U.S. states.[8]

The data reveal a striking concurrence of the geographic concentrations of top incomes and extreme wealth. New York, which hosts the nation’s highest level of income inequality, is also home to its greatest concentration of extreme wealth. ITEP estimates that households in the U.S. that are worth over $30 million (whom we will call the “ultra-rich”) collectively hold $38.9 trillion in wealth. Of this, the ultra-rich in New York State collectively hold $6.7 trillion in wealth, or about one-fifth of all wealth owned by the ultra-rich in the U.S. This makes New York State home to the most extreme wealth on both an absolute basis and in relation to its total population.

The subset of 78 billionaire households in New York hold $673 billion in wealth. This places New York second in the nation in billionaire wealth, after California (where billionaires hold $945 billion). California’s population of 39 million, however, is about twice that of New York’s (20 million). This concentration of wealth is largely due to New York’s financial industry.[9]

ITEP further estimates the unrealized capital gains held by both the ultra-rich as well as the subset of billionaires. Of the $6.7 trillion held by New York’s ultra-rich, $3.1 trillion is in unrealized capital gains (appreciated stock, real estate, or other assets that have not been sold). New York’s billionaires hold $470 billion of their $673 billion in unrealized capital gains. A significant part of these unrealized gains will not be taxed under current law, due to the step up in basis rules, which eliminate taxable gain when assets are passed on to one’s heirs at death, and because the ultra-rich often contribute their holdings to private foundations.

State-level IRS data reinforce this finding. Tax data released every few years by the IRS report total assets held by households with more than $5.45 million in wealth. The most recent dataset finds that New York is home to the third highest level of top wealth holder net assets, behind California and Florida.[10]

Most analyses underestimate extreme wealth in New York State

That New York is home to such concentrations of extreme wealth is remarkable, as survey-based measures of wealth do not show the state to be especially wealthy. According to recent U.S. Census data, New York’s median household wealth was $144,500, nearly on par with the national median of $140,800 and the 25th highest in the U.S. The same data shows the state’s average household wealth — which skews upwards as a result of concentration at the top of the distribution — to be $524,400, the 18th highest in the country.[11] Because wealth is so heavily concentrated in the hands of a few households, survey samples generally fail to adequately capture top households, undercounting extreme wealth. Tax data reported by the IRS and ITEP data, which is supplemented by tax data and Forbes data on billionaire wealth, aim to redress this undercount. In so doing, both find that rather than hosting a nationally-average amount of wealth, New York is home to a vast pool of extreme wealth.[12]

| Number of New York Tax Filers | Share of New York Tax Filers | |

|---|---|---|

| $5.45 million or more (IRS data) | 56,200 | 0.79 percent |

| Over $30 million (ITEP estimate) | 28,300 | 0.40 percent |

| Over $100 million (ITEP estimate) | 15,300 | 0.22 percent |

| Over $1 billion (ITEP estimate) | 78 | 0.0011 percent |

Sources: IRS; FPI analysis of ITEP and NYS Department of Taxation and Finance data

IRS and ITEP estimates of the top wealth holders’ collective assets are not measures of inequality, and state-level data on the entire wealth distribution remains lacking. Survey-based wealth data differ from one another in estimates of total and average wealth. Because the ITEP dataset is designed specifically to measure extreme wealth, it begins with survey data that better counts wealthy households and supplements it with Forbes data on billionaire wealth. Because Census data on median wealth undercounts top wealth it cannot be compared directly against either ITEP or IRS findings. Nevertheless, these measures are clear and important signals of the economic trajectories of the most affluent households. For New York, the data clearly chart the rise of an extraordinary concentration of wealth at the top of the distribution amid relatively average holdings by the vast majority. Further, estimates of extreme wealth have significant bearing on the policy choices and design of an effective progressive tax system.

OPTIONS FOR PROGRESSIVE TAX REFORM

These statistics point to two key policy recommendations for New York State. First, we should focus on increasing the overall progressivity of our state’s existing tax laws. Second, we should consider new reforms and instruments that would specifically target extreme wealth.[13]

Taken as a whole, New York’s tax system is regressive: the wealthy pay a lower combined state and local tax rate than those in middle income brackets, and about the same combined state and local tax rate as the poor. The state’s personal income tax (PIT) is the only progressive component of the state’s tax system, imposing higher rates on higher income earners. Sales taxes, which are levied at the state and local level, and property taxes, assessed only at the local level, are regressive, taking a larger share of income from the lowest income households. A 2019 ITEP report finds that taken together, these three taxes — income tax, sales tax, and property tax — are effectively flat across the income distribution. The bottom 40 percent of households and the top 1 percent of households pay nearly the same state and local tax rates of just over 11 percent, while the middle 55 percent pay a rate of 12.5 to 13 percent.[14]

Figure 4. New York State and Local Tax as Share of Family Incomes?

Source: ITEP

New York State’s tax system is highly reliant on the PIT. In fiscal year 2022, PIT receipts accounted for 58.4 percent of all state tax revenue. In turn, PIT revenue is highly dependent on the highest income New York tax filers. This is a result of New York’s extreme income inequality as well as its progressive PIT rates. In tax year 2020, the most recent available, 128,700 tax filers reported New York gross adjusted income above $1 million, 1.2 percent of all tax filers. These filers collectively paid 41.9 percent of all PIT liability.[15] The state’s PIT rates are modestly progressive across the income distribution as a result of recent policy changes. However, income as the sole basis for progressive taxation overlooks the far more unequally-distributed resources available to the wealthiest New Yorkers.

The findings discussed in this brief reveal enormous reserves of wealth in New York held not just by a few billionaires, but a class of top wealth holders whose numbers rival the state’s top earners. While the two groups may not neatly overlap, recent evidence suggests that top wage earnings and wealth holdings increasingly belong to the same households in the U.S.[16] Taken together, these households represent a core element of the state’s tax base. A tax system that accounts for the extreme wealth concentrated at the top of the distribution would raise more revenue from top wealth holders than a PIT that appears progressive only against the benchmark of the relatively more egalitarian income distribution.

Figure 5. New York Cumulative Income and Tax Liability, 2020

Source: NYS Department of Taxation and Finance

Moving toward such a tax system does not imply a single set of tax policies. Rather the options that the state might pursue depend on the policies’ legal status, administrative complexity, and fiscal and economic conditions. In some cases, complementary policies, or policies designed to expand over time, may be appropriate. This paper provides an overview of tax policy options that would increase revenue, increase progressivity, and reduce inequality in New York State. It covers seven options over three major areas of taxation: income taxes, business taxes, and wealth taxes.

1. Increase the Progressivity of the Personal Income Tax

Prior to the 2008 financial crisis, New York’s PIT was flat for all income earned above $40,000.[17] To fill budget gaps created by the ensuing recession, lawmakers created two higher tax brackets on income above $300,000 and $500,000. As the state’s fiscal condition improved, PIT rates were lowered for upper-middle class tax filers earning less than $1 million. The fiscal crisis that followed the Covid pandemic created a new impetus for progressive taxation. Lawmakers raised taxes on incomes over $1 million per year and created two new brackets for those earning $5 million and $25 million per year.

Figure 6. Top New York State PIT Rates in Years Following Major Changes

Source: NYS Department of Taxation and Finance; rates shown for married, joint filers

Because income and wealth are closely correlated, a progressive PIT is an effective and easily implemented tool to raise revenue from holders of extreme wealth. Lawmakers can quickly adjust PIT rates in response to fiscal conditions and target top incomes at a granular level. The recently enacted top PIT rate increases represent the first time the state’s rates began to account for the lopsided concentration of resources held at the top of the income and wealth distributions.

At a minimum, data on extreme wealth suggest that the state should not allow the new PIT rates to expire, as they are currently set to, in 2027. Further, the state should increase the rates for the “millionaire” brackets (for about $1 million, $5 million, and $25 million in annual income), and restore the $500,000 tax bracket from the post-financial crisis years.

2. Raise the Tax Rate on Long-Term Capital Gains

Capital gain is profit from the sale of assets such as stocks and bonds, real estate, intellectual property, or artwork. New York taxes capital gains at the same rates as all other income from other sources. The federal tax code, however, provides a significant tax break for long-term capital gains. While the top federal tax rate on individual income is 37 percent (and was 39.6 percent prior to the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act), the top federal tax rate on long-term capital gains is just 20 percent.[18] Numerous policymakers have long opposed this provision, which overwhelmingly benefits the rich, but the federal government has failed to remedy the problem.[19] According to the Tax Policy Center, in 2019 over 75 percent of all long-term capital gains went to the top 1 percent of earners, and only 6 percent of all long-term capital gains went to the bottom 80 percent of earners.[20] By raising tax rates on long-term capital gains for high earners, the tax system would better target extreme inequality.

3. Tax Capital Gains on a Mark-to-Market Basis

Importantly, our current tax system only taxes capital gains when the underlying asset is actually sold (for instance, when an individual sells appreciated stock). In tax parlance, this is called “realizing” the gain. This system leaves vast sums of unrealized capital gains on the table. ITEP estimates that New Yorkers with more than $30 million in assets collectively hold more than $3 trillion in unrealized capital gains — 46 percent of their total wealth. Much of this wealth will not be taxed under current law, largely due to the step up in basis rules that eliminate taxable gain when assets are passed on to one’s heirs at death. Moreover, wealthy families often borrow against accumulated assets in order to finance their lifestyles, while avoiding the tax consequences of a sale. Finally, wealthy individuals often contribute their appreciated assets to private foundations run by their own family members, avoiding tax on their gains while keeping their assets in the family for all practical purposes.

A “mark-to-market” income tax system would tax asset appreciation as it occurs, rather than waiting for the taxpayer to realize their gains. For instance, if a wealthy individual’s investment portfolio grows in value by $10 million over the course of a year, they would be treated as earning $10 million of taxable income in that year.[21]

Implementing a comprehensive mark-to-market income tax on ultra-rich taxpayers would require annual valuations of all assets in order to measure the annual gains. Critics commonly hold that this is practically impossible or else unreasonably burdensome, but tax law scholars have shown how the challenge could be met.[22] Additionally, mark-to-market rules could be applied to all of a taxpayer’s historical unrealized gains, or imposed only on a prospective basis. The former option would immediately raise windfall revenue before falling to a baseline annual revenue. A more incremental option would be to only tax current year capital gains on a mark-to-market basis, thereby foregoing the initial windfall revenue. The scope of the tax could be further limited to publicly traded instruments, so as to avoid the challenges of valuing private assets.

4. Tax the Profits of Pass-Through Businesses

The wealth of the ultra-rich generally takes the form of business holdings, whether through privately or publicly owned corporations, or through “pass-through” businesses such as partnerships and LLCs. Taxing business profits is thus an important policy tool for both reducing inequality and raising revenue. While many people think of all businesses as “corporations,” the corporation is in fact only one type of business entity. Most businesses are now formed as LLCs or partnerships, which are called “pass-through entities” because they are not subject to the corporate tax — rather, the profits are only taxed at the level of the individual owners.[23]

A starting point for taxing pass-through entities is New York’s Pass-Through Entity Tax (PTET). Currently, this tax is 100 percent rebated, bringing in no additional revenue. The tax is not designed to raise revenue, but rather to work around the federal limitation of the state and local tax deduction, and it overwhelmingly benefits the wealthy. According to ITEP, 85 percent of the benefit of the state and local tax deduction in New York State goes to the top 5 percent of income earners.[24] Because these taxpayers will still benefit from electing to pay the PTET even without a full rebate, New York should only rebate part of the tax. For instance, Connecticut rebates only 87.5 percent of its Pass-Through Entity Tax.[25]

5. Tax the Profit-Shifting of Multinational Corporations

New York should increase the amount of global intangible low-taxed income (GILTI) includible in the state corporate tax. GILTI is a provision of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act that targets the profit-shifting of multinational corporations by taxing unusually high profits in overseas jurisdictions. It is generally thought that such high profits result from shifting valuable intellectual property into foreign low-tax jurisdictions.[26]

6. Reform the Estate Tax, or Tax Inherited Income

In principle, the estate tax should function as a tax on accumulated wealth at the end of an individual’s life. However, it has largely ceased to perform this role due to a few unfortunate features of current estate tax law. Chief among them are that (i) the step up in basis rules eliminate taxable gain upon death, (ii) the estate tax exemption has continued to rise (currently, the first $26 million of an estate is exempt from federal estate tax), (iii) the wealthy can contribute their assets to a private foundation, thereby avoiding estate tax, and (iv) the estate tax planning industry has developed sophisticated tax avoidance techniques.

New York could reform any of the above features of its estate tax in order to more effectively tax accumulated wealth at death. Or, it could shift to a new, simpler inheritance tax scheme whereby inherited income is included in the recipient’s income, putting it on par with wage income and investment income.[27]

7. Enable a Direct Wealth Tax

Finally, New York could seek to impose an annual tax on the total wealth of the ultra-rich. ITEP estimates potential revenue from wealth taxes on holdings above $30 million and $1 billion at annual rates of 2, 3, and 4 percent. For New York, a 3 percent tax on wealth held above $30 million would raise $134.4 billion, greater than the entire New York State operating budget in fiscal year 2023. The same rate on wealth held above $1 billion would raise $13.2 billion.

Because a wealth tax would likely incentivize top holders to adopt tax avoidance strategies, a lower rate applied to a broader base would perform better than a higher rate on a narrower base. For New York, nearly $6 trillion of wealth is held by ultra-rich households that are not billionaires. Given that this group contains nearly 30 thousand households—rather than 78 billionaires—it makes for a sounder base for a potential wealth tax.

A state level wealth tax does face one considerable obstacles to implementation. The New York State Constitution prohibits a direct wealth tax, so a constitutional amendment would be necessary.

By Nathan Gusdorf and Andrew Perry

Nathan Gusdorf is the Executive Director and Andrew Perry is the Senior Policy Analyst at the Fiscal Policy Institute

[1] World Inequality Database, “Data: pre-tax income by U.S. state” (accessed October 2022), wid.world/data/.

[2] Carl Davis, Emma Sifre, and Spandan Marasini, “The Geographic Distribution of Extreme Wealth in the U.S.,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (October 2022), itep.org/the-geographic-distribution-of-extreme-wealth-in-the-u-s/.

[3] Estelle Sommeiller and Mark Price, “The new gilded age: Income inequality in the U.S. by state, metropolitan area, and country,” Economic Policy Institute (July 2018), epi.org/publication/the-new-gilded-age-income-inequality-in-the-u-s-by-state-metropolitan-area-and-county/.

[4] U.S. Census Bureau, “American Community Survey 2021 1-year file, Table B19083” (accessed October 2022), data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=B19083%3A%20GINI%20INDEX%20OF%20INCOME%20INEQUALITY. The District of Columbia has a higher Gini coefficient than any state.

[5] Estelle Sommeiller and Mark Price, “The new gilded age: Income inequality in the U.S. by state, metropolitan area, and country,” Economic Policy Institute (July 2018), epi.org/publication/the-new-gilded-age-income-inequality-in-the-u-s-by-state-metropolitan-area-and-county/.

[6] World Inequality Database, “Data: pre-tax income by U.S. state” (accessed October 2022), wid.world/data/.

[7] Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman, “The Rise of Income and Wealth Inequality in America: Evidence from Distributional Macroeconomic Accounts,” Journal of Economic Perspectives (Fall 2020), gabriel-zucman.eu/files/SaezZucman2020JEP.pdf.

[8] Carl Davis, Emma Sifre, and Spandan Marasini, “The Geographic Distribution of Extreme Wealth in the U.S.,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (October 2022), itep.org/the-geographic-distribution-of-extreme-wealth-in-the-u-s/.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Internal Revenue Service, “SOI Tax Stats-Top Wealthholders by State of Residence 2016” (accessed October 2022), irs.gov/statistics/soi-tax-stats-top-wealthholders-by-state-of-residence.

[11] U.S. Census Bureau, “State-Level Wealth, Asset Ownership, & Debt of Households: Detailed Tables: 2020” (accessed October 2022), census.gov/data/tables/2020/demo/wealth/state-wealth-asset-ownership.html.

[12] Census wealth data is collected by the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP). The primary purpose of the SIPP is to provide information on low-income households’ asset portfolios and use of public assistance programs. For this reason, the SIPP oversamples low-income households. By contrast, ITEP estimates are based on the Survey of Consumer Finance (SCF), which oversamples high-income households. ITEP further supplements their estimates of extreme wealth with two additional sources of data. First, ITEP uses regression analysis to generate a set of correlates between wealth data, which is available at the national level from the SCF, and IRS income data, available at the state level. These correlates produce estimates of asset ownership with the IRS income data. Because this data still fails to capture wealth at the extreme top of the distribution, ITEP further supplements their estimates with journalistic data on billionaire asset holdings compiled by Forbes. This novel methodology provides a set of estimates able to capture extreme wealth at the state level.

For a discussion of SIPP and SCF data, see Jonathan Eggleston and Mark Klee, “Reassessing Wealth Data Quality in the Survey of Income and Program Participation,” U.S. Census Bureau (February 2015), census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/working-papers/2016/demo/SEHSD-WP2016-17.pdf.

[13] A progressive tax system imposes a greater burden on those with a greater ability to pay. Both the U.S. federal income tax and the New York personal income tax impose higher tax rates on individual taxpayers with higher incomes, although the U.S. federal income tax is more progressive overall.

[14] Meg Wiehle et al. “Who Pays? A Distributional Analysis of the Tax Systems in all 50 States: Sixth Edition” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (October 2018), itep.org/whopays/.

[15] New York State Department of Taxation and Finance, “Personal Income Tax Filers, Summary Dataset 3 – Statewide Major Items and Income & Deduction Components by Liability Status and Detail Income Range: Beginning Tax Year 2015” (accessed October 2022), data.ny.gov/Government-Finance/Personal-Income-Tax-Filers-Summary-Dataset-3-State/rt8x-r6c8.

[16] Yonatan Berman and Branko Milanovic, Homoploutia: Top Labor and Capital Incomes in the United States, 1950-2020, World Inequality Lab (December 2020), wid.world/document/homoploutia-top-labor-and-capital-incomes-in-the-united-states-1950-2020-world-inequality-lab-wp-2020-27/.

[17] All rates are for joint return filers. New York State Department of Taxation and Finance, “2020 personal income tax forms: IT-201-I” and past editions (accessed October 2022), tax.ny.gov/forms/prvforms/income_tax_2020.htm.

[18] There is an additional 3.8 percent net investment income tax imposed on long-term capital gains for high-earning taxpayers as part of the Affordable Care Act.

[19] See, e.g., Galen Hendricks and Seth Hanlon, “Capital Gains Tax Preference Should Be Ended, Not Expanded” Center for American Progress (Sept. 28, 2020), americanprogress.org/article/capital-gains-tax-preference-ended-not-expanded/; Leonard Burman, “President Obama Targets the ‘Angel of Death’ Capital Gains Tax Loophole” Tax Policy Center (Jan. 18, 2015) taxpolicycenter.org/taxvox/president-obama-targets-angel-death-capital-gains-tax-loophole; William Gale and Leonard Burman, “The Case Against the Capital Gains Tax Cuts” (Sept. 1, 1997) Brookings Institute brookings.edu/opinions/the-case-against-the-capital-gains-tax-cuts.

[20] Distribution of Long-Term Capital Gains and Qualified Dividends, Tax Policy Center, taxpolicycenter.org/model-estimates/distribution-individual-income-tax-long-term-capital-gains-and-qualified-44.

[21] For years in which the individual’s portfolio loses value overall, such losses could be carried into prior or future years to offset gains, thus achieving fair tax treatment of their real economic income over time.

[22] Brian Galle, David Gamage, Darien Shanske, “Solving the Valuation Challenge: The ULTRA Method for Taxing Extreme Wealth”, Duke Law Journal (forthcoming), available at papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4036716.

[23] As of 2014, 95 percent of businesses were organized as pass-through entities. Aaron Krupkin and Adam Looney, “9 facts about pass-through businesses” Brookings Institute (May 15, 2017) brookings.edu/research/9-facts-about-pass-through-businesses.

[24] A Fair Way to Limit Tax Deductions” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, (Nov. 14, 2018) itep.org/a-fair-way-to-limit-tax-deductions/.

[25] “Pass-Through Entity Tax”, Connecticut State Department of Revenue (accessed November 2022), portal.ct.gov/DRS/Businesses/New-Business-Portal/Managing-PE-Tax.

[26] For a longer discussion of the argument for taxing GILTI, see Darien Shanske and David Gamage, “Why States Should Tax the GILTI” 91 State Tax Notes 751 (2019), available at papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3374987.

[27] For an extended analysis of the benefits and mechanics of an inheritance tax, see Lily L. Batchelder, “Leveling the Playing Field between Inherited Income and Income from Work through an Inheritance Tax”, NYU Law and Economics Research Paper Series (February 2020), available at papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3526520.