Medicaid Enrollment: Getting the Facts Straight

February 15, 2025 |

Medicaid enrollment remains 17% above re-pandemic levels, but the growth isn’t where you’d think

Key Findings:

- New York Medicaid enrollment has declined dramatically in the past 18 months, but remains 17 percent, or 1 million enrollees, above pre-pandemic levels.

- Medicaid managed care growth cannot explain this growth: Managed Long-Term Care enrollment is up by just 93,000 since before the pandemic, while Mainstream Managed Care is up less than 400,000 (and continues to decline sharply). The bulk of new enrollees (over half a million) are in “fee-for-service” (non-managed care) Medicaid.

- While the state has not explained this dramatic increase, it appears to have two sources: the Medicare Savings Program and Third Party Health Insurance Disenrollment. The former program helps New York Medicare enrollees pay Medicare premiums and copays, while the latter saves the state money by disenrolling participants from managed care when they have other insurance.

Introduction

Some commentators have recently argued that New York’s Medicaid program enrollment is out of control. This argument was laid out most forcefully by Bill Hammond in a recent piece provocatively titled “Medicaid Overdose,” which argued that enrollment in Medicaid and adjacent programs has exploded since the pandemic, is far above that of other states, and is crowding out commercial insurance.[1] New York State Budget Director Blake Washington raised the alarm about Medicaid enrollment during his budget presentation.

Stories of a New York Medicaid enrollment crisis are difficult to square with other data. Census data shows that 47.0 percent of New Yorkers were covered by employer-sponsored insurance in 2023; that’s slightly below the national average of 48.6 percent, but certainly not a crisis. Nor has that number budged much in the past decade; in 2016, it was 49.2 percent.[2] If New York’s insurance market is being taken over by Medicaid, it’s not showing up in the data.

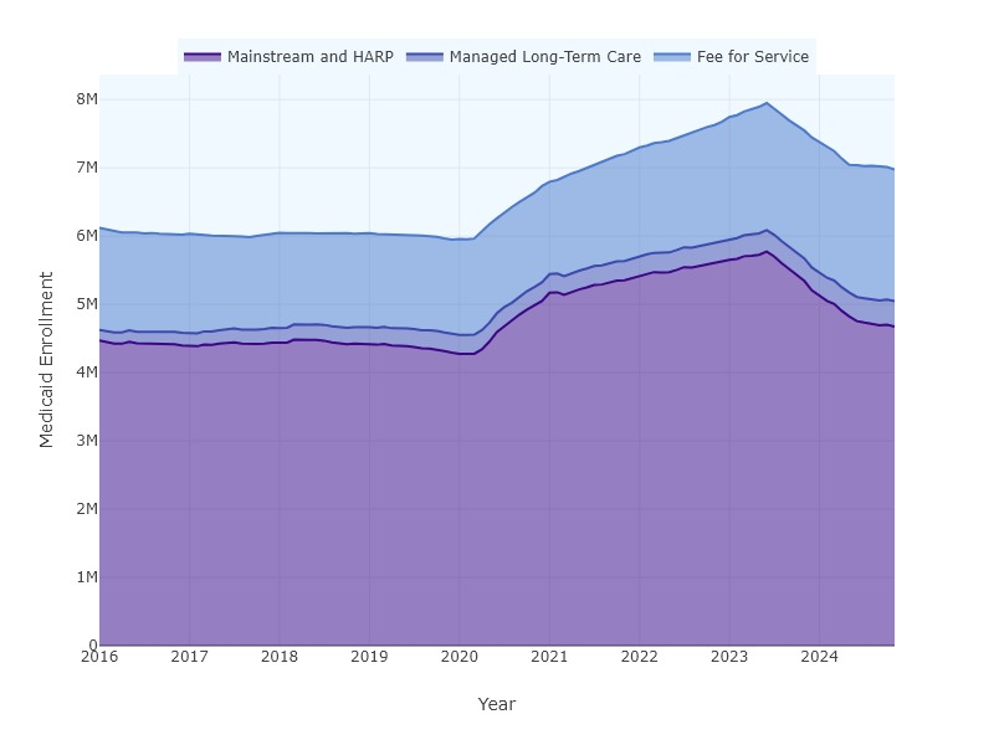

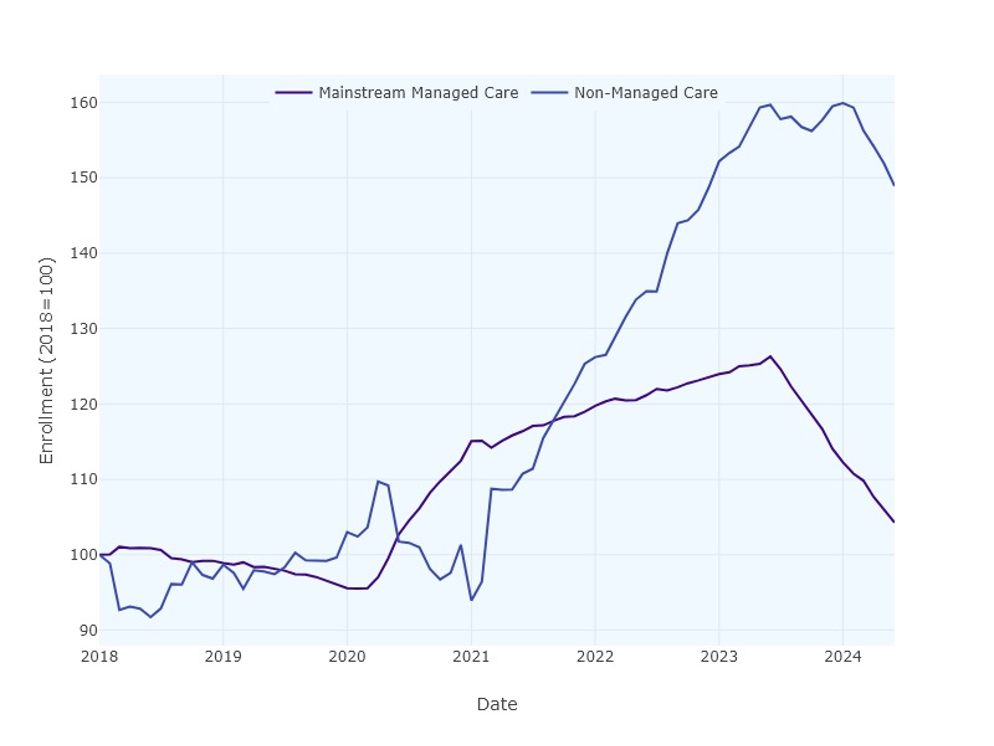

Still, New York’s Medicaid enrollment is substantial, and while it has fallen dramatically in recent years, it remains above pre-pandemic levels. Before the pandemic, roughly 6 million New Yorkers were enrolled in Medicaid (Figure 1). Enrollment peaked at 8 million in June 2023, during the pandemic-related Public Health Emergency, when federal rules prevented states from disenrolling anyone from Medicaid, even if they had found other coverage. In the year and a half since that peak, enrollment has fallen dramatically—but not back to pre-pandemic levels, at least so far. Enrollment as of December 2024 is 6.98 million, or 17.1 percent above its pre-pandemic level (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Medicaid enrollment by program category, 2016-2024.

Who are the approximately one million “new” enrollees? Answering that question requires digging into the data. Medicaid serves several distinct populations and plays several different roles in New York’s healthcare system. Medicaid is, of course, a major source of comprehensive health insurance for low-income New Yorkers – primarily through the Mainstream Managed Care program, which enrolls 4.7 million people. It is also the major payor for long-term care in the state, primarily but not exclusively through a variety of managed long-term care programs, which enroll 372,000 people. Medicaid provides help with premiums and copays for Medicare enrollees through the Medicare Savings Program, which enrolls over 1 million people. And Medicaid provides a whole range of services to a variety of smaller groups: People with intellectual and developmental disabilities, people suffering from mental illness or substance abuse, people with AIDS and traumatic brain injuries, nursing home residents, etc.

Understanding why New York Medicaid enrollment remains elevated – and what, if anything, the state should do about it – requires getting into the details. Which Medicaid programs are growing, and by how much?

Medicaid by Program: What is Growing and What is Not?

Unfortunately, the state does not release enrollment data in the granular detail we would like to see. The state’s open data portal on Medicaid enrollment provides statistics through June of 2024, and its Managed Care Enrollment Reports offer data through November 2024, but this data sorts enrollees primarily by managed care program enrollment and broad demographic details.[3] We can separate enrollees out into broad categories via managed care enrollment: 4.7 million are enrolled in mainstream managed care, and another 372,000 are enrolled in managed long-term care programs.[4] But that leaves another 1.93 million enrollees not enrolled in managed care.

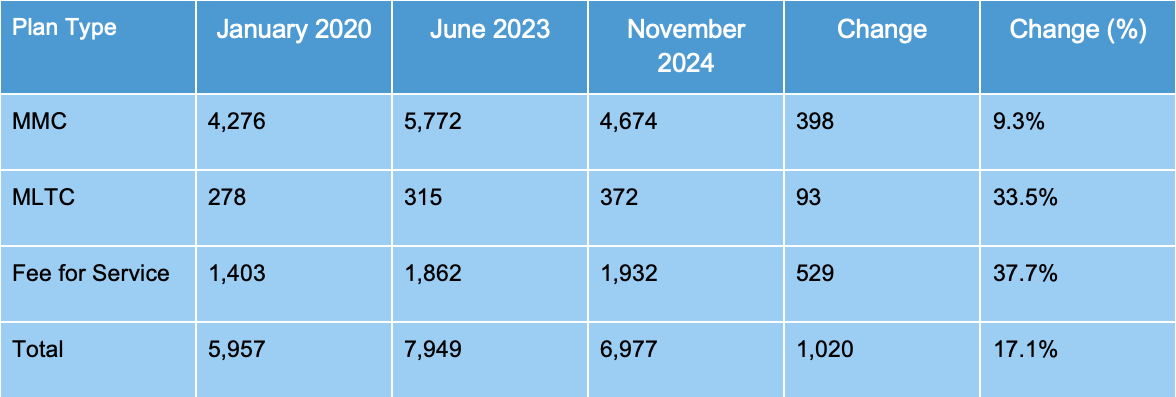

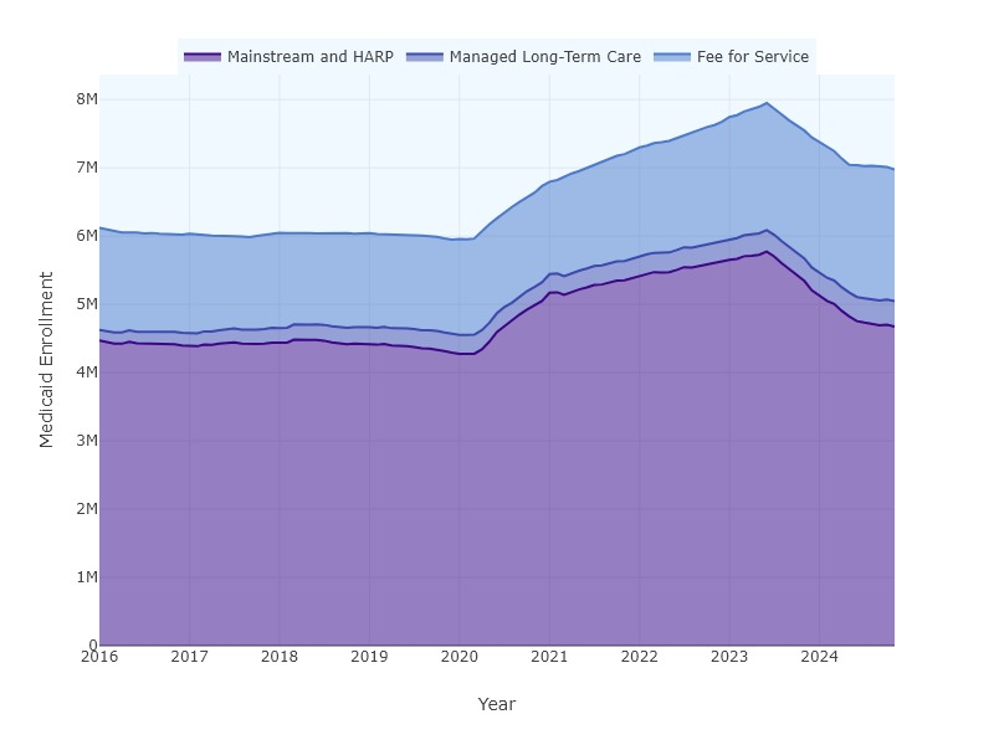

Table 1: Medicaid enrollment change by program category (millions), 2020-2024.

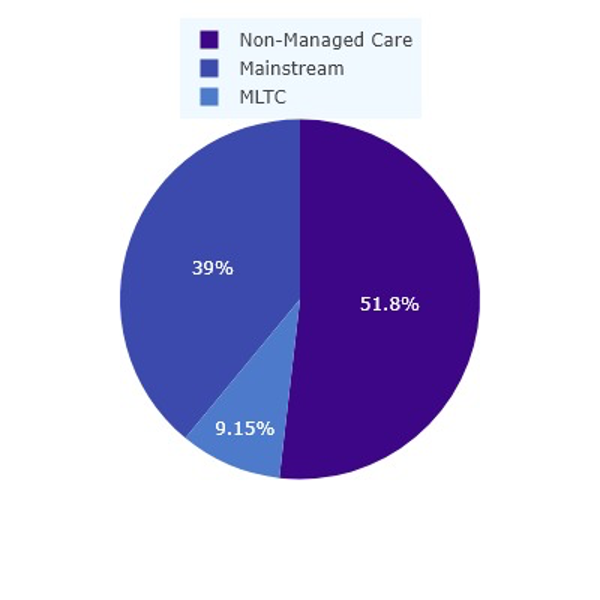

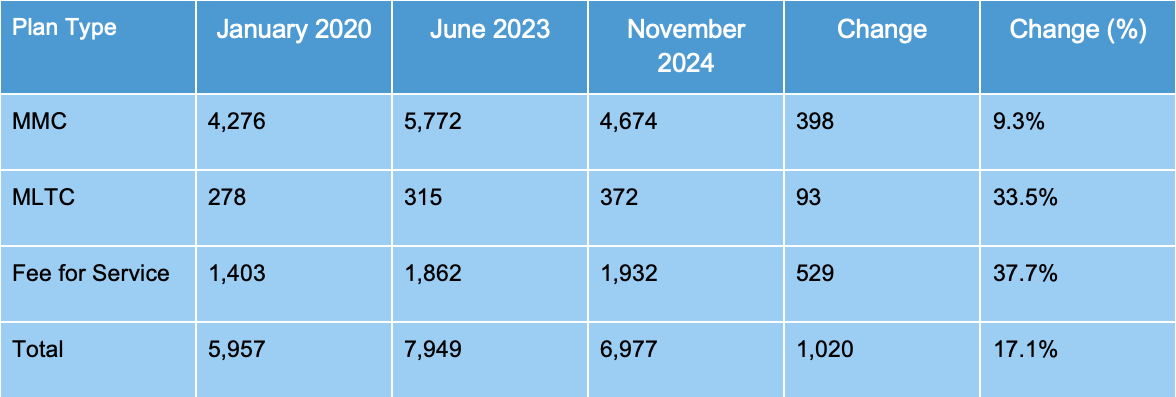

Still, the data are informative. Table 1 shows enrollment in each category in January 2020, immediately prior to the pandemic; in June 2023, at the height of the enrollment boom; and in November of 2024, the most recent data available for all categories. We can see that enrollment is higher across all three categories – but that most of the growth is in non-managed-care populations (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Medicaid enrollment by program category, 2024.

Addressing the trends one by one:

Mainstream Managed Care (MMC): This is by far the state’s largest Medicaid program, accounting for 67 percent of total enrollment. MMC is New York’s basic Medicaid program, financed by the State and administered by private insurance companies; it provides basic health insurance coverage to 4.7 million New Yorkers. It does so very efficiently: New York spent just $5,532 per member per year on MMC in 2023. (The average individual premium for an employer-sponsored plan is over $9,000.)[5]

MMC grew dramatically as millions of New Yorkers lost their jobs during the pandemic, and has shrunk by nearly 20 percent since the end of the Public Health Emergency. It remains nearly 400,000 enrollees above the pre-pandemic level. However, MMC has continued to shrink in recent months even as overall Medicaid enrollment has leveled off; the program has shed 200,000 members since May of 2024, and 65,000 in the final quarter of 2024 alone. Thus MMC enrollment may stabilize quite close to its pre-pandemic levels.

Managed Long-Term Care: New York’s Managed Long-Term Care programs provide home- and community-based long-term care to older and disabled New Yorkers, most of whom receive the bulk of their care through Medicaid. This category, which includes the State’s large so-called “Partial Cap” MLTC program (310,000 enrollees) as well as smaller programs like the Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) and Medicaid Advantage Plus. Together these programs have grown by over 33 percent since the beginning of the pandemic – a fiscally significant number, since these programs provide relatively expensive services and make up a large share of the state’s Medicaid budget. (The average cost for a dual-eligible senior in New York’s Medicaid program was over $27,000 in 2023.[6]) However, in terms of enrollment, MLTC represents just 5 percent of total Medicaid enrollment, so program growth of 93,000 in this area contributed just 9.1 percent to total Medicaid growth.

Non-managed-care (“fee-for-service”) Medicaid: The majority of New York’s excess enrollment relative to pre-pandemic levels – 529,000 enrollees, or 51.8 percent of net new enrollees – are “fee-for-service” Medicaid beneficiaries. New York’s fee-for-service Medicaid enrollment, which had hovered around 1.4 million for several years before the pandemic, leapt to over 1.9 million between 2021 and 2024 and has not declined since then. Clearly, if we want to understand why Medicaid enrollment has remained above pre-pandemic levels, we need to start here.

Unfortunately, the state does not release data on what programs this population uses, so understanding their enrollment patterns is a bit of a mystery.

Who are the non-Managed Care Medicaid enrollees?

Much of New York’s Medicaid program operates under a “mandatory managed care” framework: A recipient who enrolls in managed care, either for comprehensive health insurance or for long-term care, is required to enroll in a managed care plan operated by an insurance company. Who, then, are the 1.9 million New York Medicaid enrollees not enrolled in managed care?

There are a number of exceptions to mandatory managed care: Sub-programs and sub-populations which are either not required or not allowed to enroll in managed care.[7] Many of these populations are relatively small. For example, long-term nursing home residents in New York are excluded from managed care, but New York’s total nursing home population is only 90,000, of whom perhaps 60,000 are covered by Medicaid. This number has not increased since before the pandemic. Likewise, most enrollees covered by the Office of People with Developmental Disabilities (OPWDD) are not in managed care—but there were only 131,000 Medicaid enrollees in OPWDD as of 2023, and this figure had increased only modestly since 2020.[8] Neither of these groups seems likely to explain the enormous increase in non-managed care enrollment.

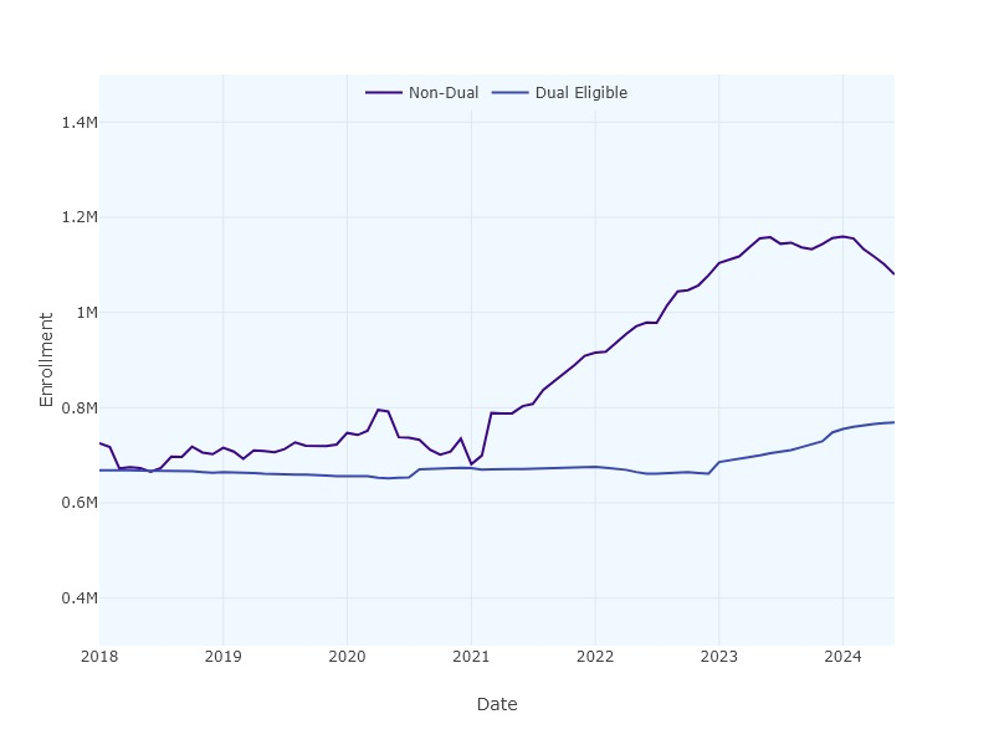

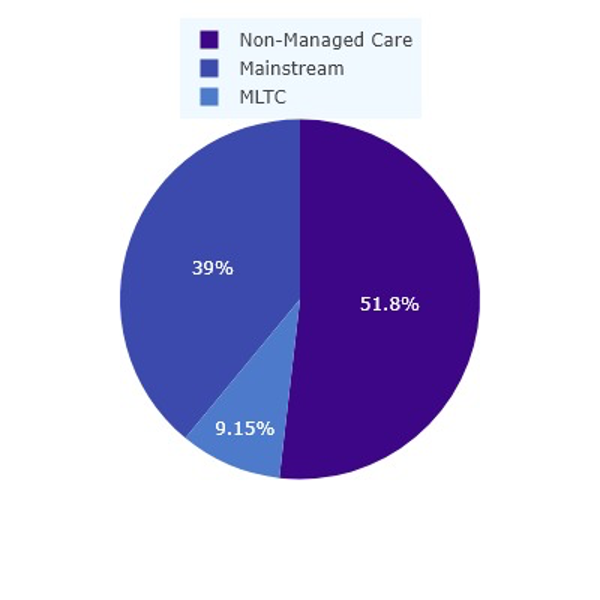

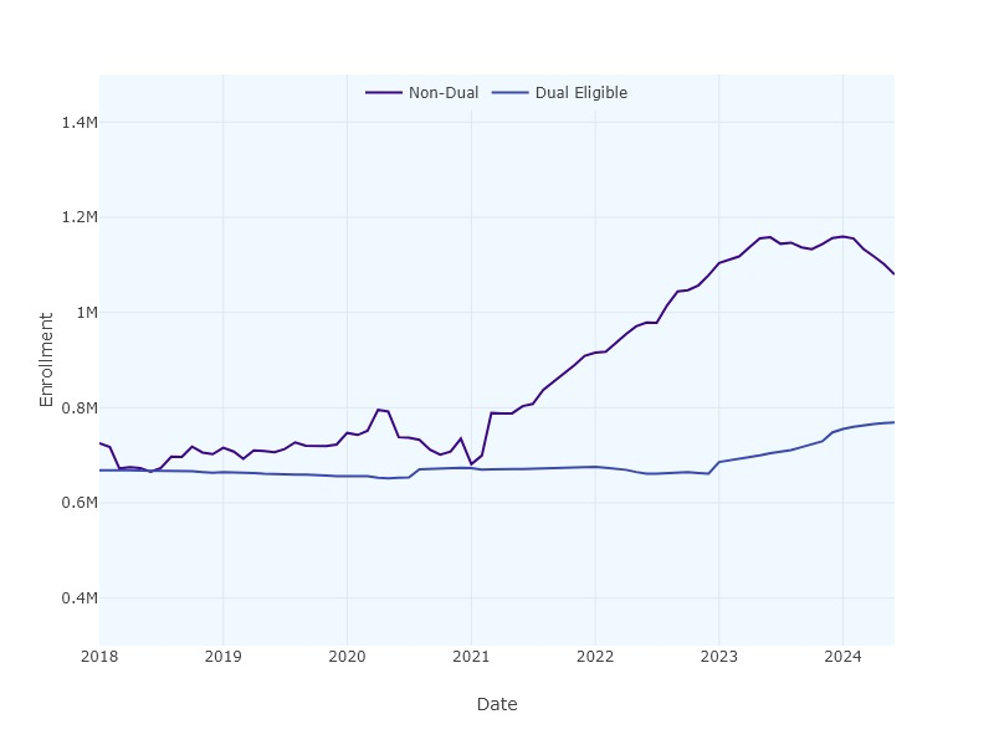

So what does? One clue emerges from separating dual-eligible enrollees (those eligible for Medicare) from non-duals (not eligible for Medicare). The trajectory of enrollment for each category is shown in Figure 3. We see an enormous increase in enrollment of non-duals, and a more gradual increase in the number of duals. More striking, however, is the timing of the increase. The pandemic began, of course, in February 2020, and Medicaid enrollment surged immediately, increasing by 800,000 through December of 2020. But non-dual, non-managed-care Medicaid enrollment didn’t take off until February of 2021. Dual-eligibles outside managed care follow yet another pattern: Their enrollment actually declined through 2021 and 2022 before beginning to increase in January 2023.

So what happened in February 2021 to increase non-dual fee-for-service enrollment? And what happened in January 2023 to increase dual fee-for-service enrollment? Answering these questions allows us to explain New York’s Medicaid growth.

Figure 3: Non-managed care Medicaid enrollment by dual-eligible status, 2018-2024.

Explaining the Non-Dual-Eligible Surge: Continuous Eligibility and Third-Party Insurance

What happened in February 2021 was the resumption of New York Medicaid’s Third Party Health Insurance Disenrollment.[9] Explaining what this is and why it matters requires some background, though.

New York was the first state in the country to offer one-year “continuous eligibility” for all Medicaid enrollees, including low-income adults, way back in 2014. (As of 2023, no other state had done it, but Oregon and Illinois were applying for waivers to follow suit.[10]) The idea of continuous eligibility is simple: Once an enrollee demonstrates eligibility for Medicaid, that individual is considered eligible for Medicaid for the following 12 months, regardless of any changes in their situation. The goal is to avoid gaps in coverage due to paperwork issues: A person shouldn’t lose healthcare coverage just because they moved and missed a letter from the state, or forgot to file a form with proof of income.

Of course, many people who file for Medicaid will in fact become ineligible at some point in this twelve-month timeframe. For example, a person may lose her job and her employer-sponsored health insurance, enroll in Medicaid, then find a new job three months later and enroll in her new employer’s health insurance. In New York, that person is still counted as a Medicaid beneficiary, even though she has other insurance and doesn’t use Medicaid.

Generally speaking, that’s not a problem: She may be a Medicaid beneficiary on paper, but she’s not actually using Medicaid for healthcare, so she’s not costing the taxpayer a dime. She remains a Medicaid enrollee just in case, but for all intents and purposes she’s off the program.

But in a managed care Medicaid system like New York’s, there could be a problem: When our protagonist enrolled in Medicaid, she was enrolled in a managed care program run by a private insurance company, and the state began paying monthly premiums to the insurance company. The state certainly shouldn’t keep paying those premiums if the enrollee has another source of coverage; that would be a waste of taxpayer money.

New York State addresses this problem through the savvy use of technology. Through a program called Third Party Liability and Recovery (TPLR), the Office of the Medicaid Inspector General checks with every insurance company in the state to find out if a beneficiary has other coverage, and unenrolls the beneficiary from managed care if he does. The beneficiary is disenrolled from Medicaid managed care, but not from Medicaid as such; she is still counted as a Medicaid enrollee, but she’s not using services and is not costing the state a dime. After their 12 months are up, they’ll cycle off Medicaid. (Of course, if she loses her job she’ll be able to return to Medicaid without suffering a gap in care.)

Crucially, these people are part of the group we’re looking at: They’re non-dual-eligible Medicaid enrollees, but they’re not in managed care.

How many of these people are there? The State doesn’t release any data on TPLR disenrollments, but even in ordinary times there must be hundreds of thousands. After all, an important role of the Medicaid program is to “catch” people who become unemployed; many of these people will find a new job within 12 months, but all of them stay formally enrolled in Medicaid.

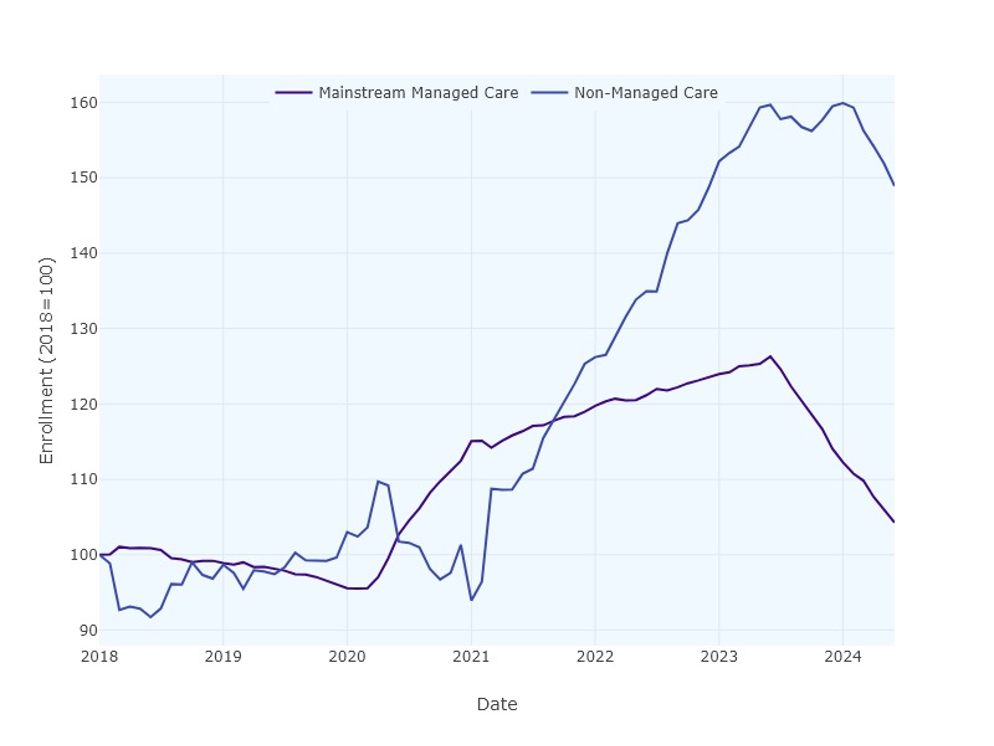

Figure 4: Enrollment of non-dual-eligible Medicaid participants in Mainstream Managed Care and non-managed-care programs, normalized.

What about during the pandemic? In 2020, the State temporarily stopped doing TPLR disenrollments between March 2020 and February 2021, then resumed. We can see the results in Figure 4. Non-managed care enrollment actually fell in 2020 (as no new participants were disenrolled from Mainstream Managed Care), but then spiked enormously starting in February 2021 (as many people who had lost their jobs during 2020 found new jobs, joined their employers’ insurance, and were disenrolled from Mainstream Managed Care.) Non-managed care non-dual enrollment rose from around 700,000 in 2020 to nearly 1.2 million in 2023, and remained at 1.1 million through mid-2024 (although it was rapidly declining as of that date). As of June 2024, this group was 333,000 above pre-pandemic levels—explaining the bulk of the 528,000 increase in non-managed-care Medicaid recipients as of November 2024.

Dual-Eligibles and the Medicare Savings Program

What about the dual-eligible group? These individuals are dually enrolled in Medicare and Medicaid, and to understand their shifts we must briefly explore the Medicare Savings Program (MSP).

In the US, older adults and disabled people typically receive the bulk of their healthcare from Medicare. Those who need long-term care (in the community or in a nursing home) typically enroll in Medicaid, since Medicare doesn’t cover long-term care.

But a much larger group enrolls in Medicaid for a different reason: They can’t afford premiums and/or cost-sharing for their Medicare coverage. Middle-class Medicare recipients typically enroll in a Medicare Supplemental (“Medigap”) insurance plan to address Medicare copays, but low-income beneficiaries may not be able to afford even the Medicare premium, much less a supplemental plan.

Most states have a Medicare Savings Program which allows these individuals to enroll in Medicaid to pay their premiums and copays, although programs vary widely in eligibility limits. New York is a national leader in offering benefits to a broad swath of seniors.

How large is this group? It’s difficult to say exactly. CMS data suggests that New York had 898,000 enrollees in December 2023 (out of 1.16 million total dual-eligible enrollees), but some unknown portion of this group also receives Medicaid long-term care; the number of dual-eligible enrollees using the program solely for premium and copay assistance is unknown.

Still, this group likely constitutes the bulk of the nearly 800,000 dual-eligible, non-managed-care Medicare enrollees in New York in June of 2024. That number was up by 113,000 from before the pandemic (and continuing to climb). Why has it increased? And why did it begin increasing only in January of 2023, long after the height of the pandemic?

The answer is likely twofold. First, at the urging of advocates, New York has significantly expanded eligibility for the program since 2021 by eliminating the asset test and raising the income eligibility limit on the program.[11] Governor Hochul recently celebrated the impact of these changes in boosting enrollment.[12]

Second, pandemic unwinding likely delayed the impact of these changes until January 2023. During the pandemic, Medicaid beneficiaries who turned 65 or otherwise became eligible for Medicare remained enrolled in Medicaid managed care plans, even if they would otherwise qualify for Medicare plus MSP. The unwinding in 2023 changed that, shifting a large number of enrollees from managed care into MSP.[13]

Conclusion

New York’s Medicaid program enrollment remains 17.1 percent over pre-pandemic levels – and this increase has sparked considerable debate, with some arguing that the increase reflects out-of-control program growth. The truth, as we have seen, is more complicated: Most of the Medicaid system’s growth since 2019 occurred in corners of the program that don’t often make headlines.

What can we expect from Medicaid enrollment in the future? It’s hard to say. It is not clear to what extent program enrollment will continue to decline in the Mainstream Managed Care program and among non-dual fee-for-service members. The latter group will be particularly difficult to track because the state has recently expanded continuous eligibility for children 0 to 6 – so many children will likely remain Medicaid enrollees on paper even if they have another source of coverage and don’t cost the state money. In the dual-eligible category, an aging population will likely drive continued enrollment in MLTC as well as the Medicare Savings Program, and MLTC costs will continue to rise. But overall enrollment figures will likely be much more heavily influenced by the much larger MSP population than by the small (but expensive) long-term care program.

Regardless of the program area, it makes little sense to ask whether “too many” New Yorkers are on Medicaid. New York State’s Medicaid program works differently from that of other states. Our continuous eligibility policies artificially inflate paper enrollment (while ensuring secure healthcare for New Yorkers and avoiding taxpayer costs). Our Medicare Savings Program saves money for older adults who have paid into Medicare but can’t afford its premiums; whether we feel that it’s a good use of funds to support them is a question of values, not numbers. Discussion of enrollment trends should be grounded in a detailed understanding of the nuances of each Medicaid program and who it serves.

Sources

[1] https://www.empirecenter.org/publications/medicaid-overdose/

[2] American Community Survey data as reported by the Kaiser Family Foundation.

[3] Open Data Portal enrollment is here, while managed care enrollment is here.

[4] Figures for Mainstream Managed Care include HARP. Figures for Managed Long-Term Care include Partial Cap, Medicaid Advantage, PACE, and FIDA-IDD.

[5] MMC cost from author’s analysis of MMC cost reports. Individual premium reported by the Kaiser Family Foundation at https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/single-coverage/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Total%20Annual%20Premium%22,%22sort%22:%22desc%22%7D

[6]https://www.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/medicaid-spending-per-full-benefit-enrollee/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Seniors%22,%22sort%22:%22desc%22%7D

[7] https://www.health.ny.gov/health_care/managed_care/plans/mmc_excl_exempt_chart.htm

[8] https://opwdd.ny.gov/data/medicaid-summary-trends

[9] https://health.ny.gov/health_care/medicaid/covid19/guidance/docs/tphi_disenrollment.pdf

[10] https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2023/sep/ensuring-continuous-eligibility-medicaid-impacts-adults

[11] https://www.medicarerights.org/media-center/new-york-medicare-savings-program-eligibility-expansion-now-in-effect

[12] https://www.governor.ny.gov/news/governor-hochul-announces-nearly-1-million-new-yorkers-enrolled-program-help-older-adults-save

Medicaid Enrollment: Getting the Facts Straight

February 15, 2025 |

Medicaid enrollment remains 17% above re-pandemic levels, but the growth isn’t where you’d think

Key Findings:

- New York Medicaid enrollment has declined dramatically in the past 18 months, but remains 17 percent, or 1 million enrollees, above pre-pandemic levels.

- Medicaid managed care growth cannot explain this growth: Managed Long-Term Care enrollment is up by just 93,000 since before the pandemic, while Mainstream Managed Care is up less than 400,000 (and continues to decline sharply). The bulk of new enrollees (over half a million) are in “fee-for-service” (non-managed care) Medicaid.

- While the state has not explained this dramatic increase, it appears to have two sources: the Medicare Savings Program and Third Party Health Insurance Disenrollment. The former program helps New York Medicare enrollees pay Medicare premiums and copays, while the latter saves the state money by disenrolling participants from managed care when they have other insurance.

Introduction

Some commentators have recently argued that New York’s Medicaid program enrollment is out of control. This argument was laid out most forcefully by Bill Hammond in a recent piece provocatively titled “Medicaid Overdose,” which argued that enrollment in Medicaid and adjacent programs has exploded since the pandemic, is far above that of other states, and is crowding out commercial insurance.[1] New York State Budget Director Blake Washington raised the alarm about Medicaid enrollment during his budget presentation.

Stories of a New York Medicaid enrollment crisis are difficult to square with other data. Census data shows that 47.0 percent of New Yorkers were covered by employer-sponsored insurance in 2023; that’s slightly below the national average of 48.6 percent, but certainly not a crisis. Nor has that number budged much in the past decade; in 2016, it was 49.2 percent.[2] If New York’s insurance market is being taken over by Medicaid, it’s not showing up in the data.

Still, New York’s Medicaid enrollment is substantial, and while it has fallen dramatically in recent years, it remains above pre-pandemic levels. Before the pandemic, roughly 6 million New Yorkers were enrolled in Medicaid (Figure 1). Enrollment peaked at 8 million in June 2023, during the pandemic-related Public Health Emergency, when federal rules prevented states from disenrolling anyone from Medicaid, even if they had found other coverage. In the year and a half since that peak, enrollment has fallen dramatically—but not back to pre-pandemic levels, at least so far. Enrollment as of December 2024 is 6.98 million, or 17.1 percent above its pre-pandemic level (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Medicaid enrollment by program category, 2016-2024.

Who are the approximately one million “new” enrollees? Answering that question requires digging into the data. Medicaid serves several distinct populations and plays several different roles in New York’s healthcare system. Medicaid is, of course, a major source of comprehensive health insurance for low-income New Yorkers – primarily through the Mainstream Managed Care program, which enrolls 4.7 million people. It is also the major payor for long-term care in the state, primarily but not exclusively through a variety of managed long-term care programs, which enroll 372,000 people. Medicaid provides help with premiums and copays for Medicare enrollees through the Medicare Savings Program, which enrolls over 1 million people. And Medicaid provides a whole range of services to a variety of smaller groups: People with intellectual and developmental disabilities, people suffering from mental illness or substance abuse, people with AIDS and traumatic brain injuries, nursing home residents, etc.

Understanding why New York Medicaid enrollment remains elevated – and what, if anything, the state should do about it – requires getting into the details. Which Medicaid programs are growing, and by how much?

Medicaid by Program: What is Growing and What is Not?

Unfortunately, the state does not release enrollment data in the granular detail we would like to see. The state’s open data portal on Medicaid enrollment provides statistics through June of 2024, and its Managed Care Enrollment Reports offer data through November 2024, but this data sorts enrollees primarily by managed care program enrollment and broad demographic details.[3] We can separate enrollees out into broad categories via managed care enrollment: 4.7 million are enrolled in mainstream managed care, and another 372,000 are enrolled in managed long-term care programs.[4] But that leaves another 1.93 million enrollees not enrolled in managed care.

Table 1: Medicaid enrollment change by program category (millions), 2020-2024.

Still, the data are informative. Table 1 shows enrollment in each category in January 2020, immediately prior to the pandemic; in June 2023, at the height of the enrollment boom; and in November of 2024, the most recent data available for all categories. We can see that enrollment is higher across all three categories – but that most of the growth is in non-managed-care populations (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Medicaid enrollment by program category, 2024.

Addressing the trends one by one:

Mainstream Managed Care (MMC): This is by far the state’s largest Medicaid program, accounting for 67 percent of total enrollment. MMC is New York’s basic Medicaid program, financed by the State and administered by private insurance companies; it provides basic health insurance coverage to 4.7 million New Yorkers. It does so very efficiently: New York spent just $5,532 per member per year on MMC in 2023. (The average individual premium for an employer-sponsored plan is over $9,000.)[5]

MMC grew dramatically as millions of New Yorkers lost their jobs during the pandemic, and has shrunk by nearly 20 percent since the end of the Public Health Emergency. It remains nearly 400,000 enrollees above the pre-pandemic level. However, MMC has continued to shrink in recent months even as overall Medicaid enrollment has leveled off; the program has shed 200,000 members since May of 2024, and 65,000 in the final quarter of 2024 alone. Thus MMC enrollment may stabilize quite close to its pre-pandemic levels.

Managed Long-Term Care: New York’s Managed Long-Term Care programs provide home- and community-based long-term care to older and disabled New Yorkers, most of whom receive the bulk of their care through Medicaid. This category, which includes the State’s large so-called “Partial Cap” MLTC program (310,000 enrollees) as well as smaller programs like the Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) and Medicaid Advantage Plus. Together these programs have grown by over 33 percent since the beginning of the pandemic – a fiscally significant number, since these programs provide relatively expensive services and make up a large share of the state’s Medicaid budget. (The average cost for a dual-eligible senior in New York’s Medicaid program was over $27,000 in 2023.[6]) However, in terms of enrollment, MLTC represents just 5 percent of total Medicaid enrollment, so program growth of 93,000 in this area contributed just 9.1 percent to total Medicaid growth.

Non-managed-care (“fee-for-service”) Medicaid: The majority of New York’s excess enrollment relative to pre-pandemic levels – 529,000 enrollees, or 51.8 percent of net new enrollees – are “fee-for-service” Medicaid beneficiaries. New York’s fee-for-service Medicaid enrollment, which had hovered around 1.4 million for several years before the pandemic, leapt to over 1.9 million between 2021 and 2024 and has not declined since then. Clearly, if we want to understand why Medicaid enrollment has remained above pre-pandemic levels, we need to start here.

Unfortunately, the state does not release data on what programs this population uses, so understanding their enrollment patterns is a bit of a mystery.

Who are the non-Managed Care Medicaid enrollees?

Much of New York’s Medicaid program operates under a “mandatory managed care” framework: A recipient who enrolls in managed care, either for comprehensive health insurance or for long-term care, is required to enroll in a managed care plan operated by an insurance company. Who, then, are the 1.9 million New York Medicaid enrollees not enrolled in managed care?

There are a number of exceptions to mandatory managed care: Sub-programs and sub-populations which are either not required or not allowed to enroll in managed care.[7] Many of these populations are relatively small. For example, long-term nursing home residents in New York are excluded from managed care, but New York’s total nursing home population is only 90,000, of whom perhaps 60,000 are covered by Medicaid. This number has not increased since before the pandemic. Likewise, most enrollees covered by the Office of People with Developmental Disabilities (OPWDD) are not in managed care—but there were only 131,000 Medicaid enrollees in OPWDD as of 2023, and this figure had increased only modestly since 2020.[8] Neither of these groups seems likely to explain the enormous increase in non-managed care enrollment.

So what does? One clue emerges from separating dual-eligible enrollees (those eligible for Medicare) from non-duals (not eligible for Medicare). The trajectory of enrollment for each category is shown in Figure 3. We see an enormous increase in enrollment of non-duals, and a more gradual increase in the number of duals. More striking, however, is the timing of the increase. The pandemic began, of course, in February 2020, and Medicaid enrollment surged immediately, increasing by 800,000 through December of 2020. But non-dual, non-managed-care Medicaid enrollment didn’t take off until February of 2021. Dual-eligibles outside managed care follow yet another pattern: Their enrollment actually declined through 2021 and 2022 before beginning to increase in January 2023.

So what happened in February 2021 to increase non-dual fee-for-service enrollment? And what happened in January 2023 to increase dual fee-for-service enrollment? Answering these questions allows us to explain New York’s Medicaid growth.

Figure 3: Non-managed care Medicaid enrollment by dual-eligible status, 2018-2024.

Explaining the Non-Dual-Eligible Surge: Continuous Eligibility and Third-Party Insurance

What happened in February 2021 was the resumption of New York Medicaid’s Third Party Health Insurance Disenrollment.[9] Explaining what this is and why it matters requires some background, though.

New York was the first state in the country to offer one-year “continuous eligibility” for all Medicaid enrollees, including low-income adults, way back in 2014. (As of 2023, no other state had done it, but Oregon and Illinois were applying for waivers to follow suit.[10]) The idea of continuous eligibility is simple: Once an enrollee demonstrates eligibility for Medicaid, that individual is considered eligible for Medicaid for the following 12 months, regardless of any changes in their situation. The goal is to avoid gaps in coverage due to paperwork issues: A person shouldn’t lose healthcare coverage just because they moved and missed a letter from the state, or forgot to file a form with proof of income.

Of course, many people who file for Medicaid will in fact become ineligible at some point in this twelve-month timeframe. For example, a person may lose her job and her employer-sponsored health insurance, enroll in Medicaid, then find a new job three months later and enroll in her new employer’s health insurance. In New York, that person is still counted as a Medicaid beneficiary, even though she has other insurance and doesn’t use Medicaid.

Generally speaking, that’s not a problem: She may be a Medicaid beneficiary on paper, but she’s not actually using Medicaid for healthcare, so she’s not costing the taxpayer a dime. She remains a Medicaid enrollee just in case, but for all intents and purposes she’s off the program.

But in a managed care Medicaid system like New York’s, there could be a problem: When our protagonist enrolled in Medicaid, she was enrolled in a managed care program run by a private insurance company, and the state began paying monthly premiums to the insurance company. The state certainly shouldn’t keep paying those premiums if the enrollee has another source of coverage; that would be a waste of taxpayer money.

New York State addresses this problem through the savvy use of technology. Through a program called Third Party Liability and Recovery (TPLR), the Office of the Medicaid Inspector General checks with every insurance company in the state to find out if a beneficiary has other coverage, and unenrolls the beneficiary from managed care if he does. The beneficiary is disenrolled from Medicaid managed care, but not from Medicaid as such; she is still counted as a Medicaid enrollee, but she’s not using services and is not costing the state a dime. After their 12 months are up, they’ll cycle off Medicaid. (Of course, if she loses her job she’ll be able to return to Medicaid without suffering a gap in care.)

Crucially, these people are part of the group we’re looking at: They’re non-dual-eligible Medicaid enrollees, but they’re not in managed care.

How many of these people are there? The State doesn’t release any data on TPLR disenrollments, but even in ordinary times there must be hundreds of thousands. After all, an important role of the Medicaid program is to “catch” people who become unemployed; many of these people will find a new job within 12 months, but all of them stay formally enrolled in Medicaid.

Figure 4: Enrollment of non-dual-eligible Medicaid participants in Mainstream Managed Care and non-managed-care programs, normalized.

What about during the pandemic? In 2020, the State temporarily stopped doing TPLR disenrollments between March 2020 and February 2021, then resumed. We can see the results in Figure 4. Non-managed care enrollment actually fell in 2020 (as no new participants were disenrolled from Mainstream Managed Care), but then spiked enormously starting in February 2021 (as many people who had lost their jobs during 2020 found new jobs, joined their employers’ insurance, and were disenrolled from Mainstream Managed Care.) Non-managed care non-dual enrollment rose from around 700,000 in 2020 to nearly 1.2 million in 2023, and remained at 1.1 million through mid-2024 (although it was rapidly declining as of that date). As of June 2024, this group was 333,000 above pre-pandemic levels—explaining the bulk of the 528,000 increase in non-managed-care Medicaid recipients as of November 2024.

Dual-Eligibles and the Medicare Savings Program

What about the dual-eligible group? These individuals are dually enrolled in Medicare and Medicaid, and to understand their shifts we must briefly explore the Medicare Savings Program (MSP).

In the US, older adults and disabled people typically receive the bulk of their healthcare from Medicare. Those who need long-term care (in the community or in a nursing home) typically enroll in Medicaid, since Medicare doesn’t cover long-term care.

But a much larger group enrolls in Medicaid for a different reason: They can’t afford premiums and/or cost-sharing for their Medicare coverage. Middle-class Medicare recipients typically enroll in a Medicare Supplemental (“Medigap”) insurance plan to address Medicare copays, but low-income beneficiaries may not be able to afford even the Medicare premium, much less a supplemental plan.

Most states have a Medicare Savings Program which allows these individuals to enroll in Medicaid to pay their premiums and copays, although programs vary widely in eligibility limits. New York is a national leader in offering benefits to a broad swath of seniors.

How large is this group? It’s difficult to say exactly. CMS data suggests that New York had 898,000 enrollees in December 2023 (out of 1.16 million total dual-eligible enrollees), but some unknown portion of this group also receives Medicaid long-term care; the number of dual-eligible enrollees using the program solely for premium and copay assistance is unknown.

Still, this group likely constitutes the bulk of the nearly 800,000 dual-eligible, non-managed-care Medicare enrollees in New York in June of 2024. That number was up by 113,000 from before the pandemic (and continuing to climb). Why has it increased? And why did it begin increasing only in January of 2023, long after the height of the pandemic?

The answer is likely twofold. First, at the urging of advocates, New York has significantly expanded eligibility for the program since 2021 by eliminating the asset test and raising the income eligibility limit on the program.[11] Governor Hochul recently celebrated the impact of these changes in boosting enrollment.[12]

Second, pandemic unwinding likely delayed the impact of these changes until January 2023. During the pandemic, Medicaid beneficiaries who turned 65 or otherwise became eligible for Medicare remained enrolled in Medicaid managed care plans, even if they would otherwise qualify for Medicare plus MSP. The unwinding in 2023 changed that, shifting a large number of enrollees from managed care into MSP.[13]

Conclusion

New York’s Medicaid program enrollment remains 17.1 percent over pre-pandemic levels – and this increase has sparked considerable debate, with some arguing that the increase reflects out-of-control program growth. The truth, as we have seen, is more complicated: Most of the Medicaid system’s growth since 2019 occurred in corners of the program that don’t often make headlines.

What can we expect from Medicaid enrollment in the future? It’s hard to say. It is not clear to what extent program enrollment will continue to decline in the Mainstream Managed Care program and among non-dual fee-for-service members. The latter group will be particularly difficult to track because the state has recently expanded continuous eligibility for children 0 to 6 – so many children will likely remain Medicaid enrollees on paper even if they have another source of coverage and don’t cost the state money. In the dual-eligible category, an aging population will likely drive continued enrollment in MLTC as well as the Medicare Savings Program, and MLTC costs will continue to rise. But overall enrollment figures will likely be much more heavily influenced by the much larger MSP population than by the small (but expensive) long-term care program.

Regardless of the program area, it makes little sense to ask whether “too many” New Yorkers are on Medicaid. New York State’s Medicaid program works differently from that of other states. Our continuous eligibility policies artificially inflate paper enrollment (while ensuring secure healthcare for New Yorkers and avoiding taxpayer costs). Our Medicare Savings Program saves money for older adults who have paid into Medicare but can’t afford its premiums; whether we feel that it’s a good use of funds to support them is a question of values, not numbers. Discussion of enrollment trends should be grounded in a detailed understanding of the nuances of each Medicaid program and who it serves.

Sources

[1] https://www.empirecenter.org/publications/medicaid-overdose/

[2] American Community Survey data as reported by the Kaiser Family Foundation.

[3] Open Data Portal enrollment is here, while managed care enrollment is here.

[4] Figures for Mainstream Managed Care include HARP. Figures for Managed Long-Term Care include Partial Cap, Medicaid Advantage, PACE, and FIDA-IDD.

[5] MMC cost from author’s analysis of MMC cost reports. Individual premium reported by the Kaiser Family Foundation at https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/single-coverage/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Total%20Annual%20Premium%22,%22sort%22:%22desc%22%7D

[6]https://www.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/medicaid-spending-per-full-benefit-enrollee/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Seniors%22,%22sort%22:%22desc%22%7D

[7] https://www.health.ny.gov/health_care/managed_care/plans/mmc_excl_exempt_chart.htm

[8] https://opwdd.ny.gov/data/medicaid-summary-trends

[9] https://health.ny.gov/health_care/medicaid/covid19/guidance/docs/tphi_disenrollment.pdf

[10] https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2023/sep/ensuring-continuous-eligibility-medicaid-impacts-adults

[11] https://www.medicarerights.org/media-center/new-york-medicare-savings-program-eligibility-expansion-now-in-effect

[12] https://www.governor.ny.gov/news/governor-hochul-announces-nearly-1-million-new-yorkers-enrolled-program-help-older-adults-save