New York State’s Reserves: A User’s Guide

September 21, 2023 |

By Andrew Perry, Senior Policy Analyst

September 21, 2023

Key Findings

- All economies go through cyclical upswings and downturns.

- State treasuries should deposit money into reserve accounts during economic upswings, and spend their reserves during downturns, in order to stabilize public spending.

- Reserves can allow state expenditures to align with longer-run revenue trends, rather than overspending during growth periods and cutting spending during slowdowns.

- New York has a large population of high earners who receive substantial income in the form of bonuses, capital gains, and business profits. These sources of income are particularly subject to cyclical economic volatility.

- By contrast, when structural economic changes cause long-term spending shortfalls, states must make permanent tax and spending changes to stabilize their revenues.

Introduction

New York State has generated significant budget surpluses in recent years as its economy recovered more quickly than expected from the Covid pandemic. Like most other U.S. states, New York saved a considerable portion of these surpluses in its fiscal reserve funds, building a buffer against fiscal stress during future economic downturns. With the Division of the Budget projecting an economic slowdown and depressed revenue in the years ahead, the appropriate use of the State’s fiscal reserves is now a subject of debate. This post will provide an overview on why fiscal reserves exist, and how they can be used to smooth out fluctuations in the economic cycle and maintain stable public services.

The economic cycle

The economic cycle — periodic expansions and contractions of economic activity — can take a significant toll on public finances at all levels of government. Cyclical economic downturns raise unemployment and reduce personal income, driving down public sector revenue. This in turn means higher costs for governments that provide public assistance, such as Medicaid. The federal government can respond to such fiscal shortfalls through either austerity measures — balancing budgets using a combination of tax increases and spending cuts — or debt-financed deficit spending. State and local governments, however, are generally prohibited from deficit spending by state constitutions. For this reason, state and local governments often rely on spending cuts, tax increases, or a combination of both, to address spending shortfalls. However, by adhering to a rational fiscal reserve policy, state and local governments can stabilize public spending through economic downturns while avoiding cuts to services.

New York’s historically low reserves

Prior to the Covid pandemic, New York’s fiscal reserves were inadequate to meaningfully offset fiscal shortfalls during recessions. Over the decade preceding Covid, New York’s fiscal reserves as a share of its budget were consistently among the ten lowest U.S. states. These meager fiscal reserves left the State dependent on budget cuts and tax hikes to balance budgets during past recessions. Following the 2008 financial crisis, the State raised taxes on top earners and imposed across-the-board spending cuts to balance its budget. In the wake of Covid, deep cuts were averted by tax rate increases for corporate and high-income earners as well as unprecedented federal relief.

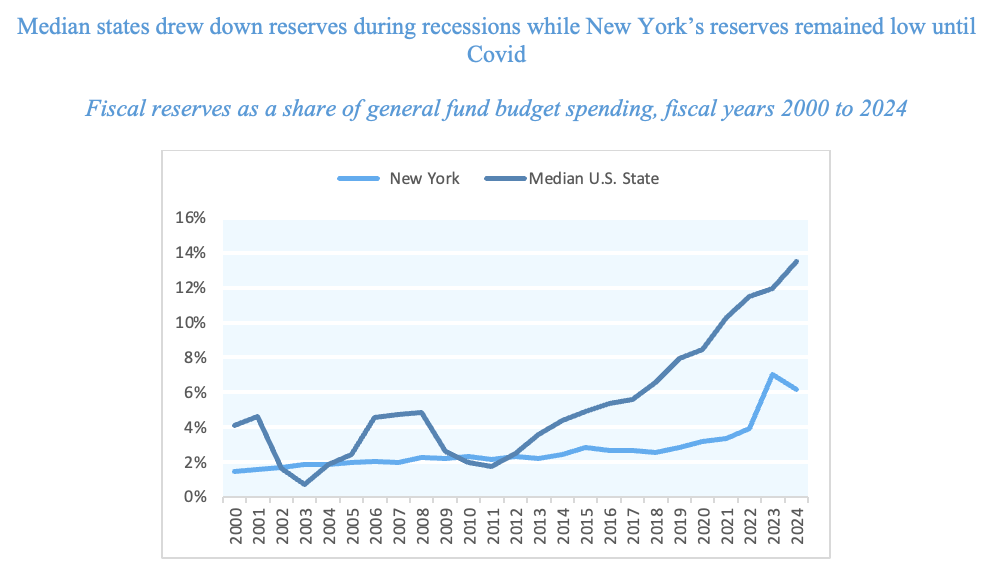

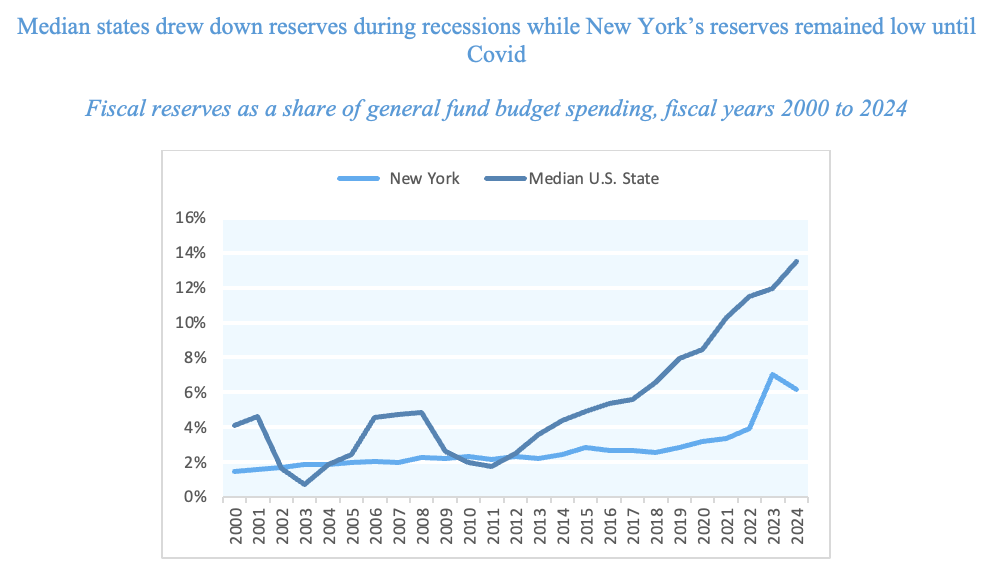

By contrast, typical U.S. states held modest reserves ahead of recent recessions. These states were able to draw down reserve levels during the 2001 and 2007-09 recessions to help balance budgets. New York’s low reserve levels during these recessions were inadequate to offer any fiscal relief. While the severity of the 2007-09 recession was such that most U.S. states still took austerity measures, the complementary use of fiscal reserves reduced the need for sharp budget cuts, unlike states without meaningful fiscal reserves like New York. During the economic recovery of the 2010s, most U.S. states began building reserve balances to better protect themselves against future recessions. New York, by contrast, failed to meaningfully build reserves until the Covid pandemic. As such, the State’s reserves remained at their low levels through recent downturns, including the 2001 and 2007-09 recessions, unable to provide any fiscal relief (see figure 1).[i]

Figure 1. Median states drew down reserves during recessions while New York’s reserves remained low until Covid

Source: NASBO. Note: for interstate comparability, reserve balances reflect only rainy day funds; New York also maintains fiscal reserves in other reserve accounts, as discussed below.

Smoothing the economic cycle

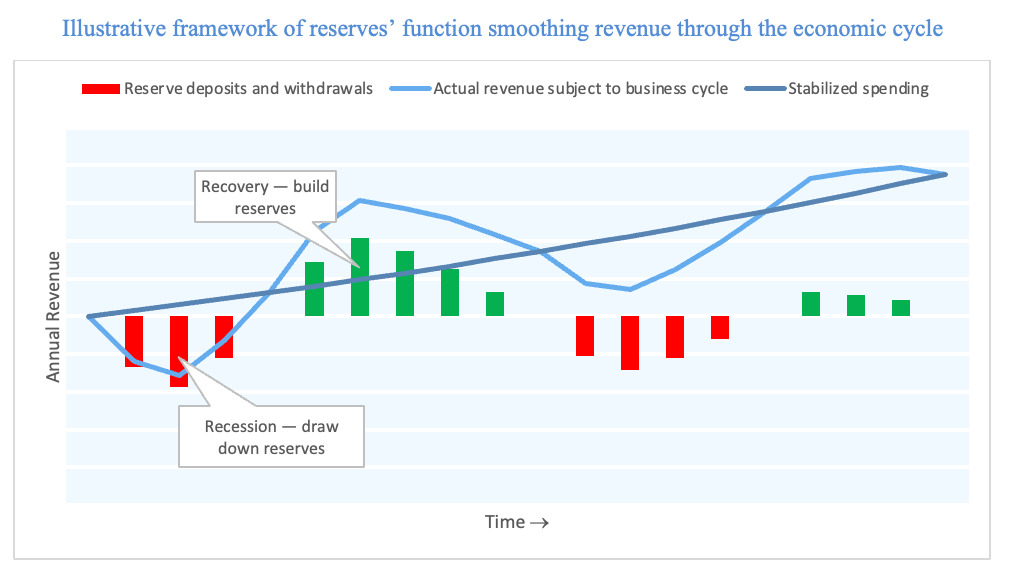

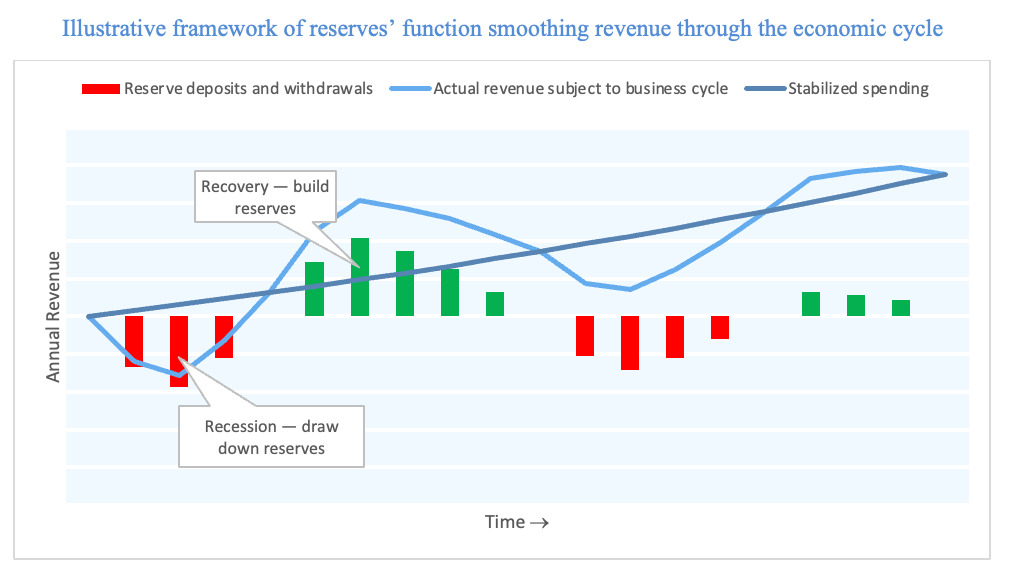

The median U.S. state’s experience with reserves exemplifies their purpose: to smooth spending through the economic cycle (periodic economic fluctuations, characterized by contractions and expansions of economic activity). Reserves can allow state expenditures to align with longer-run revenue trends, rather than accelerating spending to above-trend levels during economic expansions and austerity in the wake of recessions. By making deposits to reserves in years of faster-than-usual economic growth, as often happens in recoveries from recessions, and withdrawing during downturns, states can aim to maintain steady public services through economic fluctuations, bridging short-run fiscal imbalances without budget cuts (see figure 2).

Figure 2. Illustrative framework of reserves’ function smoothing revenue through the economic cycle

Fiscal imbalances, however, are not all identical. Reserves are the best policy tool to close cyclical fiscal gaps — shortfalls that result from economic cycles, including national recessions, economic shocks like natural disasters, or capital markets volatility. A framework illustrating reserves’ utility smoothing cyclical fluctuations is provided in figure 2.

By contrast, reserves are a weaker solution to gaps driven by structural economic forces — long-term changes of a state’s economic or fiscal system. These structural forces include deindustrialization (which precipitated the New York City fiscal crisis of the late 1970s) and other long-run trends that erode a regional economic base. Structural trends also include changes that affect the tax system’s ability to raise revenue from a growing tax base. For instance, a change in technology that causes consumers to shift from taxable goods (e.g., CDs and DVDs) to non-taxed services (e.g., streaming services), would cause a long-run erosion in the tax base despite growth in consumer spending. Reserves are ill-suited to address these structural changes, which require changes to the State’s fiscal structure.

Using reserves to smooth spending through economic ups and downs is doubly important for New York. New York has the nation’s highest level of income inequality, driven by its concentration of extremely high-income earners. These high incomes are largely comprised of non-wage income, including capital gains and business income, which is more volatile across years than wage income. As such, New York’s tax revenue tends to fluctuate with the fortunes of its highest income earners. Fiscal reserves can allow the State to smooth this year-to-year revenue volatility by making deposits in years with high capital gains and deploying reserves in the wake of weak market performance.

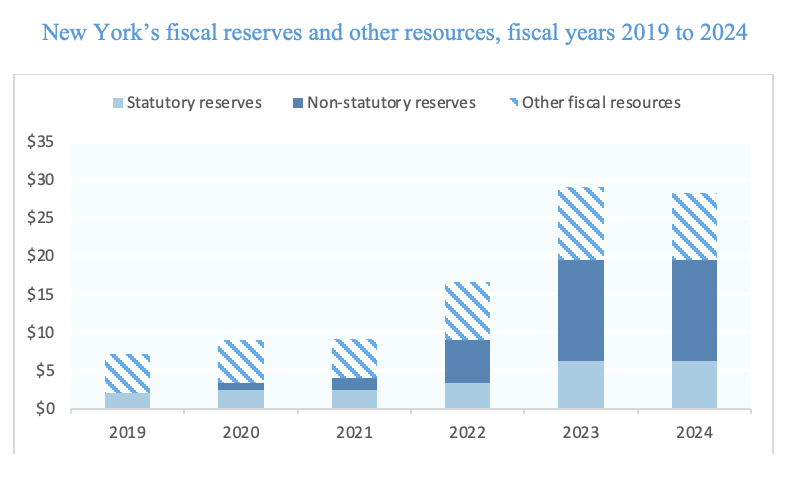

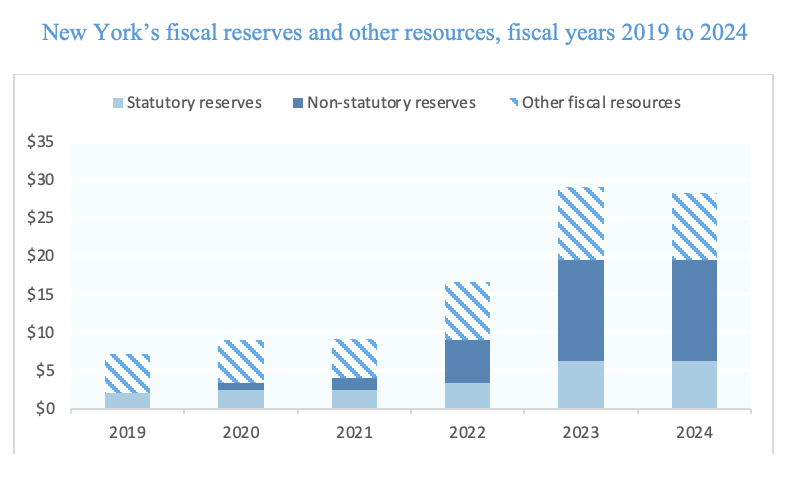

Post-Covid: New York’s fiscal reserve funds begin to grow

Extraordinary federal Covid relief allowed states, including New York, to avert spending cuts and accelerate — or in the case of New York, begin in earnest — deposits to fiscal reserve funds. In fiscal year 2022, the State, buoyed by federal funding, revenue action, and a strong economic recovery, deposited $5.0 billion into its fiscal reserves, more than doubling their total fiscal reserves to $9.0 billion. The following fiscal year similarly delivered higher-than-expected revenue, allowing the State to deposit $10.6 billion, again more than doubling its reserve balance to $19.5 billion. This deposit brings the State’s fiscal reserves to 15.6 percent of State operating funds spending — above its long-run goal of 15 percent. Other fiscal resources — accounts in the general fund not allocated as fiscal reserves, but nevertheless available to support the budget — also grew over this period, from $5.2 billion prior to Covid to $9.6 billion in fiscal year 2023. Figure 3 illustrates growth in the State’s fiscal reserves — which comprise statutory and non-statutory reserves — and other non-reserve fiscal resources. These reserve and other fiscal accounts are discussed in greater detail in the appendix below.

Figure 3. New York’s fiscal reserves and other resources, fiscal years 2019 to 2024

Source: New York State Division of Budget. Note: fiscal year 2024 projection of other fiscal resources uses enacted budget financial plan baseline adjusted to reflect higher-than-anticipated balances at the end of the first quarter.

Given current economic uncertainty and the possibility of an economic downturn, the State does not anticipate net deposits to its reserves for fiscal year 2024 or subsequent years. One pool of other fiscal resources is set to grow under the fiscal year 2024 enacted budget financial plan: recurring $1.45 billion reservations to the operating cost account — funds set aside in the general fund to cover State operations cost inflation, including higher costs that result from labor negotiations. These deposits will push the operating cost account from $1.8 billion in fiscal year 2024 to $6.15 billion by fiscal year 2027. These funds will be available to support general state operating costs in the years ahead.

Reserves as an alternative to austerity

In its fiscal year 2024 enacted budget financial plan, the State projected considerable fiscal gaps in fiscal years 2025 through 2027. Unlike historical gaps of similar size, however, the State’s current gaps result from an anticipated, rather than a current, economic downturn. Further, as FPI noted in a recent brief, financial plans typically project modest outyear gaps even in times of greater fiscal and economic stability. For this reason, there is considerable uncertainty around each year’s gap, such that aggregating the outyear gaps provides an unreliable measure of fiscal stress ahead.

If a recession materializes, fiscal reserves should be deployed to stabilize public services. If the depth and duration of a recession were known in advance, the prudent policy response would fully draw down reserves at an even pace through the downturn to best maintain fiscal stability, and rebuild the funds as the economy recovers. In reality, the uncertainty inherent to the economic cycle complicates the full use of reserves. Drawing down reserves too quickly carries risks if a downturn persists longer than expected. Conversely, over-cautious use of reserves may lead to unnecessary budget cuts, which impede economic recovery. How these risks are balanced depends on the causes and severity of a recession and the availability of federal support, as well as the effect of the downturn on the State’s spending programs. Clarity around the State’s economic forecasting models used to project future revenue would allow the public to more clearly understand if fiscal reserves are being effectively deployed.

While nearly all U.S. states averted both cuts and reserves drawdowns during the last recession due to federal relief, they cannot rely on the expectation of unprecedented federal relief in future crises, given political uncertainty and the ad hoc nature of local fiscal support at the federal level. Rather, states should plan proactively to use a combination of reserve deployment and, as needed, targeted tax increases, to avoid budget cuts during recessions. While use of reserves is preferable to tax increases, serious recessions may require complementary revenue action. These potential tax increases should focus on high-income earners to avoid exacerbating recessionary effects on the hardest-hit New Yorkers.

Appendix: New York State’s fiscal reserves and other resources

New York’s principal reserves are comprised of three funds: two statutory funds — the rainy day reserve fund (RDRF) and tax stabilization reserve fund (TSRF) — the use of which is governed by State law, and an informal account — economic uncertainties — that can be deployed by the State on an ad hoc basis. Beyond these principal reserves, the State general fund is comprised of other reserve resources set aside from certain sources or for specific contingencies.

Principal Statutory Reserves:

- The Rainy Day Reserve Fund (RDRF), the State’s primary statutory reserve, is reserved for use during economic recessions. Withdrawals from the fund can only be made after the coincident economic index (CEI) — a monthly composite indicator published by the New York State Department of Labor that tracks current economic data — declines for five consecutive months. Since 1970, five-month declines in the CEI have always aligned with national recessions.

The RDRF statute limits maximum annual deposits to the fund and its total balances. These limits have been raised in each of the last two enacted budgets, reflecting policymakers’ recent seriousness about building fiscal reserves. In fiscal year 2023, the RDRF balance limit was raised from 5 to 15 percent of general fund spending. In fiscal year 2024, the balance was again increased to 25 percent of general fund spending. The maximum annual deposit was also raised from 3 to 15 percent of general fund spending. The increase in annual deposits affords the State authority to shift recent surpluses from unrestricted economic uncertainties reserves (described below) into the restricted RDRF. The State plans to make a deposit at the end of fiscal year 2024, pending fiscal and economic conditions.[ii]

- The Tax Stabilization Reserve Fund (TSRF), the State’s other statutory reserve, is designed to automatically smooth year-to-year revenue fluctuations. The TSRF statute requires any general fund surplus, up to 0.2 percent of general fund spending per year per year, to be deposited into the fund such that the fund balance is maintained at two percent of annual general fund spending. In years in which general fund revenue falls below spending at the end of the fiscal year, funds are transferred from the TSRF to balance the budget.[iii]

Principal Non-Statutory Reserves:

- Economic uncertainties refers to unrestricted general fund balances designated as fiscal reserves. Because these funds are not restricted under State law, they afford the State more flexibility than statutory reserves. Together with the two statutory reserves (referred to as “rainy day reserves”), these funds comprise the State’s three “principal reserve funds.”

Other Fiscal Resources:

- Other fiscal resources comprise additional funds in the State’s general fund. These funds include the extraordinary monetary settlements fund, funded by settlements with major financial institutions in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, which has disbursed proceeds to a range of State spending, including fiscal reserves. Other reserve resources include funds set aside to support the State’s future debt service liability, as well as to cover above-trend operating cost growth as the State reaches collective bargaining settlements.

[i] National Association of State Budget Officers (NASBO), “Rainy Day Fund Historical Data” (accessed June 2023), https://www.nasbo.org/reports-data/historical-data.

[ii] New York State Division of Budget, Fiscal Year 20204 Enacted Budget Financial Plan (July 2023), https://www.budget.ny.gov/pubs/archive/fy24/en/fy24en-fp.pdf.

[iii] State Finance Law, Chapter 56 Article 6, Section 92, https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/laws/STF/92.

New York State’s Reserves: A User’s Guide

September 21, 2023 |

By Andrew Perry, Senior Policy Analyst

September 21, 2023

Key Findings

- All economies go through cyclical upswings and downturns.

- State treasuries should deposit money into reserve accounts during economic upswings, and spend their reserves during downturns, in order to stabilize public spending.

- Reserves can allow state expenditures to align with longer-run revenue trends, rather than overspending during growth periods and cutting spending during slowdowns.

- New York has a large population of high earners who receive substantial income in the form of bonuses, capital gains, and business profits. These sources of income are particularly subject to cyclical economic volatility.

- By contrast, when structural economic changes cause long-term spending shortfalls, states must make permanent tax and spending changes to stabilize their revenues.

Introduction

New York State has generated significant budget surpluses in recent years as its economy recovered more quickly than expected from the Covid pandemic. Like most other U.S. states, New York saved a considerable portion of these surpluses in its fiscal reserve funds, building a buffer against fiscal stress during future economic downturns. With the Division of the Budget projecting an economic slowdown and depressed revenue in the years ahead, the appropriate use of the State’s fiscal reserves is now a subject of debate. This post will provide an overview on why fiscal reserves exist, and how they can be used to smooth out fluctuations in the economic cycle and maintain stable public services.

The economic cycle

The economic cycle — periodic expansions and contractions of economic activity — can take a significant toll on public finances at all levels of government. Cyclical economic downturns raise unemployment and reduce personal income, driving down public sector revenue. This in turn means higher costs for governments that provide public assistance, such as Medicaid. The federal government can respond to such fiscal shortfalls through either austerity measures — balancing budgets using a combination of tax increases and spending cuts — or debt-financed deficit spending. State and local governments, however, are generally prohibited from deficit spending by state constitutions. For this reason, state and local governments often rely on spending cuts, tax increases, or a combination of both, to address spending shortfalls. However, by adhering to a rational fiscal reserve policy, state and local governments can stabilize public spending through economic downturns while avoiding cuts to services.

New York’s historically low reserves

Prior to the Covid pandemic, New York’s fiscal reserves were inadequate to meaningfully offset fiscal shortfalls during recessions. Over the decade preceding Covid, New York’s fiscal reserves as a share of its budget were consistently among the ten lowest U.S. states. These meager fiscal reserves left the State dependent on budget cuts and tax hikes to balance budgets during past recessions. Following the 2008 financial crisis, the State raised taxes on top earners and imposed across-the-board spending cuts to balance its budget. In the wake of Covid, deep cuts were averted by tax rate increases for corporate and high-income earners as well as unprecedented federal relief.

By contrast, typical U.S. states held modest reserves ahead of recent recessions. These states were able to draw down reserve levels during the 2001 and 2007-09 recessions to help balance budgets. New York’s low reserve levels during these recessions were inadequate to offer any fiscal relief. While the severity of the 2007-09 recession was such that most U.S. states still took austerity measures, the complementary use of fiscal reserves reduced the need for sharp budget cuts, unlike states without meaningful fiscal reserves like New York. During the economic recovery of the 2010s, most U.S. states began building reserve balances to better protect themselves against future recessions. New York, by contrast, failed to meaningfully build reserves until the Covid pandemic. As such, the State’s reserves remained at their low levels through recent downturns, including the 2001 and 2007-09 recessions, unable to provide any fiscal relief (see figure 1).[i]

Figure 1. Median states drew down reserves during recessions while New York’s reserves remained low until Covid

Source: NASBO. Note: for interstate comparability, reserve balances reflect only rainy day funds; New York also maintains fiscal reserves in other reserve accounts, as discussed below.

Smoothing the economic cycle

The median U.S. state’s experience with reserves exemplifies their purpose: to smooth spending through the economic cycle (periodic economic fluctuations, characterized by contractions and expansions of economic activity). Reserves can allow state expenditures to align with longer-run revenue trends, rather than accelerating spending to above-trend levels during economic expansions and austerity in the wake of recessions. By making deposits to reserves in years of faster-than-usual economic growth, as often happens in recoveries from recessions, and withdrawing during downturns, states can aim to maintain steady public services through economic fluctuations, bridging short-run fiscal imbalances without budget cuts (see figure 2).

Figure 2. Illustrative framework of reserves’ function smoothing revenue through the economic cycle

Fiscal imbalances, however, are not all identical. Reserves are the best policy tool to close cyclical fiscal gaps — shortfalls that result from economic cycles, including national recessions, economic shocks like natural disasters, or capital markets volatility. A framework illustrating reserves’ utility smoothing cyclical fluctuations is provided in figure 2.

By contrast, reserves are a weaker solution to gaps driven by structural economic forces — long-term changes of a state’s economic or fiscal system. These structural forces include deindustrialization (which precipitated the New York City fiscal crisis of the late 1970s) and other long-run trends that erode a regional economic base. Structural trends also include changes that affect the tax system’s ability to raise revenue from a growing tax base. For instance, a change in technology that causes consumers to shift from taxable goods (e.g., CDs and DVDs) to non-taxed services (e.g., streaming services), would cause a long-run erosion in the tax base despite growth in consumer spending. Reserves are ill-suited to address these structural changes, which require changes to the State’s fiscal structure.

Using reserves to smooth spending through economic ups and downs is doubly important for New York. New York has the nation’s highest level of income inequality, driven by its concentration of extremely high-income earners. These high incomes are largely comprised of non-wage income, including capital gains and business income, which is more volatile across years than wage income. As such, New York’s tax revenue tends to fluctuate with the fortunes of its highest income earners. Fiscal reserves can allow the State to smooth this year-to-year revenue volatility by making deposits in years with high capital gains and deploying reserves in the wake of weak market performance.

Post-Covid: New York’s fiscal reserve funds begin to grow

Extraordinary federal Covid relief allowed states, including New York, to avert spending cuts and accelerate — or in the case of New York, begin in earnest — deposits to fiscal reserve funds. In fiscal year 2022, the State, buoyed by federal funding, revenue action, and a strong economic recovery, deposited $5.0 billion into its fiscal reserves, more than doubling their total fiscal reserves to $9.0 billion. The following fiscal year similarly delivered higher-than-expected revenue, allowing the State to deposit $10.6 billion, again more than doubling its reserve balance to $19.5 billion. This deposit brings the State’s fiscal reserves to 15.6 percent of State operating funds spending — above its long-run goal of 15 percent. Other fiscal resources — accounts in the general fund not allocated as fiscal reserves, but nevertheless available to support the budget — also grew over this period, from $5.2 billion prior to Covid to $9.6 billion in fiscal year 2023. Figure 3 illustrates growth in the State’s fiscal reserves — which comprise statutory and non-statutory reserves — and other non-reserve fiscal resources. These reserve and other fiscal accounts are discussed in greater detail in the appendix below.

Figure 3. New York’s fiscal reserves and other resources, fiscal years 2019 to 2024

Source: New York State Division of Budget. Note: fiscal year 2024 projection of other fiscal resources uses enacted budget financial plan baseline adjusted to reflect higher-than-anticipated balances at the end of the first quarter.

Given current economic uncertainty and the possibility of an economic downturn, the State does not anticipate net deposits to its reserves for fiscal year 2024 or subsequent years. One pool of other fiscal resources is set to grow under the fiscal year 2024 enacted budget financial plan: recurring $1.45 billion reservations to the operating cost account — funds set aside in the general fund to cover State operations cost inflation, including higher costs that result from labor negotiations. These deposits will push the operating cost account from $1.8 billion in fiscal year 2024 to $6.15 billion by fiscal year 2027. These funds will be available to support general state operating costs in the years ahead.

Reserves as an alternative to austerity

In its fiscal year 2024 enacted budget financial plan, the State projected considerable fiscal gaps in fiscal years 2025 through 2027. Unlike historical gaps of similar size, however, the State’s current gaps result from an anticipated, rather than a current, economic downturn. Further, as FPI noted in a recent brief, financial plans typically project modest outyear gaps even in times of greater fiscal and economic stability. For this reason, there is considerable uncertainty around each year’s gap, such that aggregating the outyear gaps provides an unreliable measure of fiscal stress ahead.

If a recession materializes, fiscal reserves should be deployed to stabilize public services. If the depth and duration of a recession were known in advance, the prudent policy response would fully draw down reserves at an even pace through the downturn to best maintain fiscal stability, and rebuild the funds as the economy recovers. In reality, the uncertainty inherent to the economic cycle complicates the full use of reserves. Drawing down reserves too quickly carries risks if a downturn persists longer than expected. Conversely, over-cautious use of reserves may lead to unnecessary budget cuts, which impede economic recovery. How these risks are balanced depends on the causes and severity of a recession and the availability of federal support, as well as the effect of the downturn on the State’s spending programs. Clarity around the State’s economic forecasting models used to project future revenue would allow the public to more clearly understand if fiscal reserves are being effectively deployed.

While nearly all U.S. states averted both cuts and reserves drawdowns during the last recession due to federal relief, they cannot rely on the expectation of unprecedented federal relief in future crises, given political uncertainty and the ad hoc nature of local fiscal support at the federal level. Rather, states should plan proactively to use a combination of reserve deployment and, as needed, targeted tax increases, to avoid budget cuts during recessions. While use of reserves is preferable to tax increases, serious recessions may require complementary revenue action. These potential tax increases should focus on high-income earners to avoid exacerbating recessionary effects on the hardest-hit New Yorkers.

Appendix: New York State’s fiscal reserves and other resources

New York’s principal reserves are comprised of three funds: two statutory funds — the rainy day reserve fund (RDRF) and tax stabilization reserve fund (TSRF) — the use of which is governed by State law, and an informal account — economic uncertainties — that can be deployed by the State on an ad hoc basis. Beyond these principal reserves, the State general fund is comprised of other reserve resources set aside from certain sources or for specific contingencies.

Principal Statutory Reserves:

- The Rainy Day Reserve Fund (RDRF), the State’s primary statutory reserve, is reserved for use during economic recessions. Withdrawals from the fund can only be made after the coincident economic index (CEI) — a monthly composite indicator published by the New York State Department of Labor that tracks current economic data — declines for five consecutive months. Since 1970, five-month declines in the CEI have always aligned with national recessions.

The RDRF statute limits maximum annual deposits to the fund and its total balances. These limits have been raised in each of the last two enacted budgets, reflecting policymakers’ recent seriousness about building fiscal reserves. In fiscal year 2023, the RDRF balance limit was raised from 5 to 15 percent of general fund spending. In fiscal year 2024, the balance was again increased to 25 percent of general fund spending. The maximum annual deposit was also raised from 3 to 15 percent of general fund spending. The increase in annual deposits affords the State authority to shift recent surpluses from unrestricted economic uncertainties reserves (described below) into the restricted RDRF. The State plans to make a deposit at the end of fiscal year 2024, pending fiscal and economic conditions.[ii]

- The Tax Stabilization Reserve Fund (TSRF), the State’s other statutory reserve, is designed to automatically smooth year-to-year revenue fluctuations. The TSRF statute requires any general fund surplus, up to 0.2 percent of general fund spending per year per year, to be deposited into the fund such that the fund balance is maintained at two percent of annual general fund spending. In years in which general fund revenue falls below spending at the end of the fiscal year, funds are transferred from the TSRF to balance the budget.[iii]

Principal Non-Statutory Reserves:

- Economic uncertainties refers to unrestricted general fund balances designated as fiscal reserves. Because these funds are not restricted under State law, they afford the State more flexibility than statutory reserves. Together with the two statutory reserves (referred to as “rainy day reserves”), these funds comprise the State’s three “principal reserve funds.”

Other Fiscal Resources:

- Other fiscal resources comprise additional funds in the State’s general fund. These funds include the extraordinary monetary settlements fund, funded by settlements with major financial institutions in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, which has disbursed proceeds to a range of State spending, including fiscal reserves. Other reserve resources include funds set aside to support the State’s future debt service liability, as well as to cover above-trend operating cost growth as the State reaches collective bargaining settlements.

[i] National Association of State Budget Officers (NASBO), “Rainy Day Fund Historical Data” (accessed June 2023), https://www.nasbo.org/reports-data/historical-data.

[ii] New York State Division of Budget, Fiscal Year 20204 Enacted Budget Financial Plan (July 2023), https://www.budget.ny.gov/pubs/archive/fy24/en/fy24en-fp.pdf.

[iii] State Finance Law, Chapter 56 Article 6, Section 92, https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/laws/STF/92.