Troubling trends in New York’s small group market

July 15, 2025 |

By Bailey Hu, Health Policy Analyst, & Michael Kinnucan, Director of Health Policy

Prior to the passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2010, small business employers in New York and other states often had difficulty buying affordable health insurance, especially if their employees were in poor health. The ACA helped provide better options for workers and their families by regulating offerings in the “small group” health insurance market, which serves businesses with up to 100 employees. However, recent administrative data shows alarming trends: not only is New York’s small group market shrinking rapidly, but premiums have also risen much faster than inflation in many regions of the state. If these trends continue, the small group market could become increasingly imbalanced, burdening employers and employees alike.

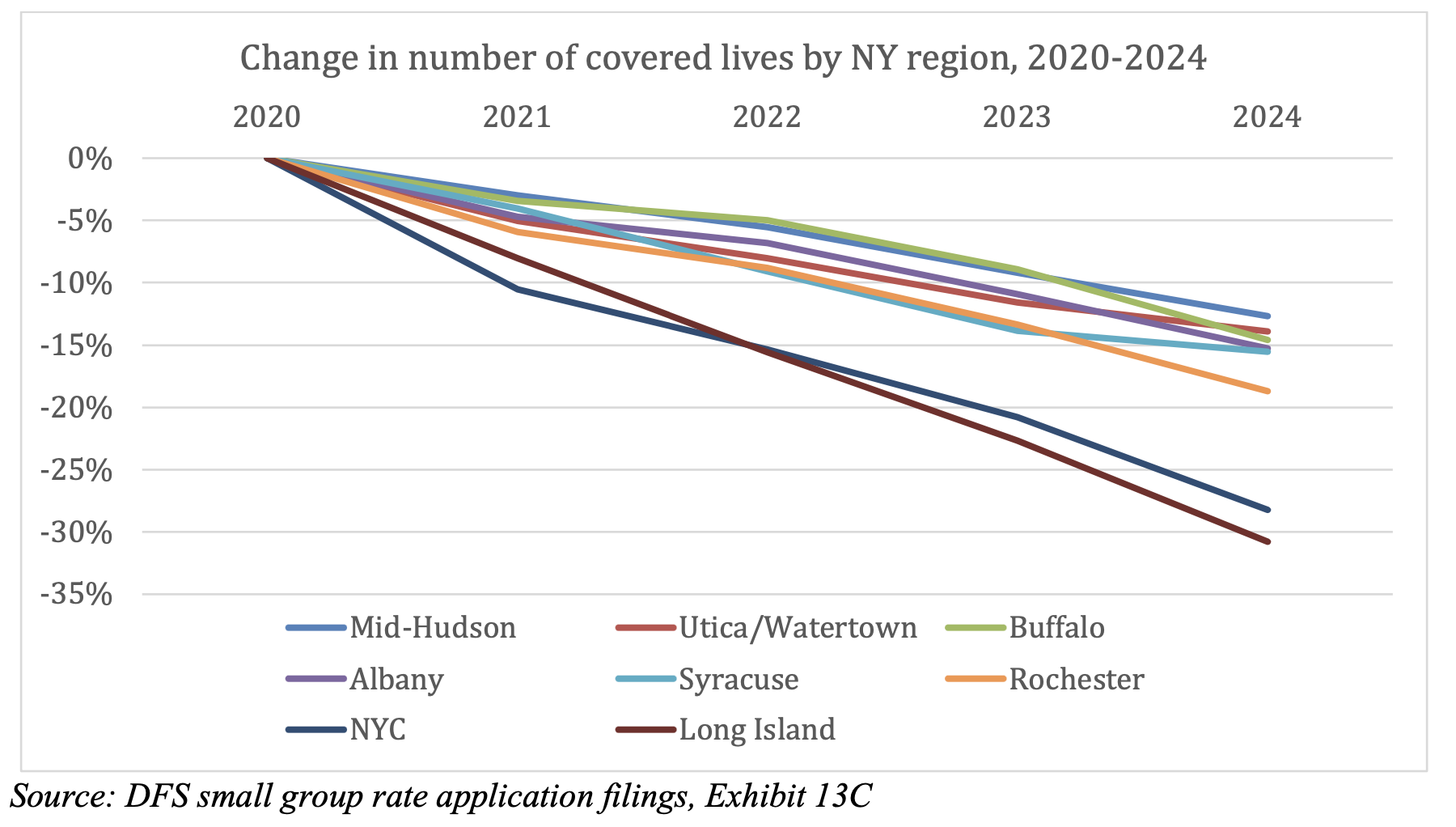

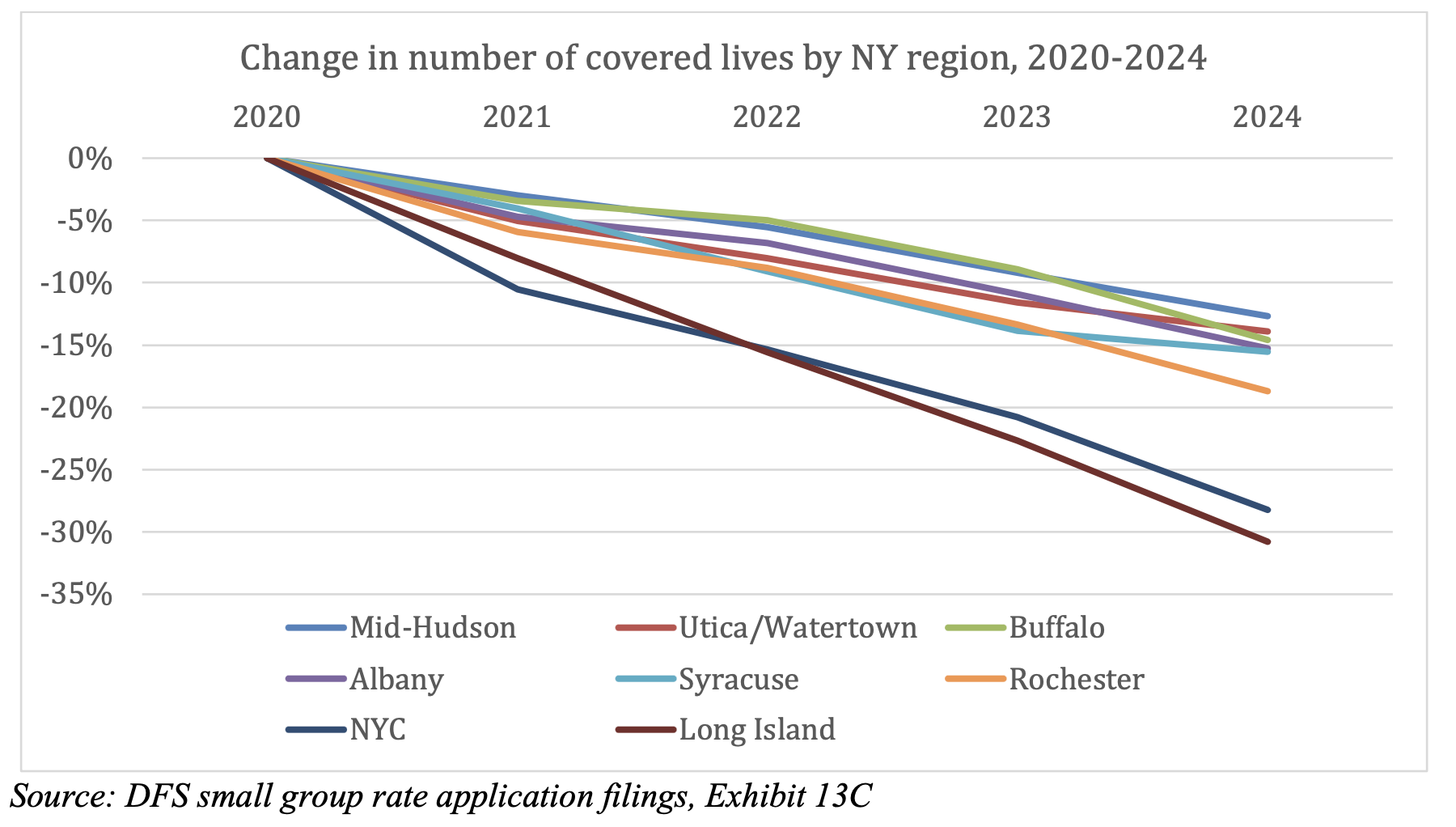

Insurer-reported data collected by the New York Department of Financial Services (DFS) reflect a small and shrinking market. From 2020 to 2024, the number of covered lives in the small group market dropped from more than 960,000 to under 740,000, a loss of 24 percent. Three quarters of the decline in enrollees came from the New York City metro region and Long Island alone, which have shrunk at much faster rates than the rest of the state.

Premiums have also risen considerably across many regions of the state, even after accounting for the high rate of inflation in recent years. The Rochester area (including part of the Finger Lakes region) saw average premiums for a gold-tier plan rise by 45 percent from 2020-2024, or 20 percent after adjusting for inflation. NYC and Long Island had increases of 38 and 36 percent, respectively, during the same time period (14 and 13 percent after adjusting for inflation). High growth rates help explain extraordinarily high premiums in many regions. In March 2024, the average gold-tier premium in NYC’s small group market was $1,274, followed closely by Long Island’s $1,257 average premium for the same plan type.

Rising prices can create a negative feedback loop where small businesses, which can no longer afford insurance through the small group market, look for alternative options or stop offering coverage entirely. Since those who leave the small group market are more likely to have healthier or younger employees, the remaining pool of enrollees becomes even more imbalanced, driving premiums up further. Insurance costs are also tied to the price of health care, which has risen across all regions of New York in recent years.

To tackle these worrying trends in the small group market, policymakers should take a two-pronged approach. First, to address the drop in enrollment, alternatives to the small group market such as Professional Employer Organizations – which group small businesses together under one plan – should be more tightly regulated. Second, since insurance premiums are ultimately driven by health care prices, capping the prices hospitals and other providers charge can help make insurance more affordable. Policymakers have an array of tools to do so, ranging from the Fair Pricing Act to the New York Health Act to the state’s former hospital price regulation system. Taking action now can help ensure small businesses have comprehensive and affordable coverage for years to come.

Troubling trends in New York’s small group market

July 15, 2025 |

By Bailey Hu, Health Policy Analyst, & Michael Kinnucan, Director of Health Policy

Prior to the passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2010, small business employers in New York and other states often had difficulty buying affordable health insurance, especially if their employees were in poor health. The ACA helped provide better options for workers and their families by regulating offerings in the “small group” health insurance market, which serves businesses with up to 100 employees. However, recent administrative data shows alarming trends: not only is New York’s small group market shrinking rapidly, but premiums have also risen much faster than inflation in many regions of the state. If these trends continue, the small group market could become increasingly imbalanced, burdening employers and employees alike.

Insurer-reported data collected by the New York Department of Financial Services (DFS) reflect a small and shrinking market. From 2020 to 2024, the number of covered lives in the small group market dropped from more than 960,000 to under 740,000, a loss of 24 percent. Three quarters of the decline in enrollees came from the New York City metro region and Long Island alone, which have shrunk at much faster rates than the rest of the state.

Premiums have also risen considerably across many regions of the state, even after accounting for the high rate of inflation in recent years. The Rochester area (including part of the Finger Lakes region) saw average premiums for a gold-tier plan rise by 45 percent from 2020-2024, or 20 percent after adjusting for inflation. NYC and Long Island had increases of 38 and 36 percent, respectively, during the same time period (14 and 13 percent after adjusting for inflation). High growth rates help explain extraordinarily high premiums in many regions. In March 2024, the average gold-tier premium in NYC’s small group market was $1,274, followed closely by Long Island’s $1,257 average premium for the same plan type.

Rising prices can create a negative feedback loop where small businesses, which can no longer afford insurance through the small group market, look for alternative options or stop offering coverage entirely. Since those who leave the small group market are more likely to have healthier or younger employees, the remaining pool of enrollees becomes even more imbalanced, driving premiums up further. Insurance costs are also tied to the price of health care, which has risen across all regions of New York in recent years.

To tackle these worrying trends in the small group market, policymakers should take a two-pronged approach. First, to address the drop in enrollment, alternatives to the small group market such as Professional Employer Organizations – which group small businesses together under one plan – should be more tightly regulated. Second, since insurance premiums are ultimately driven by health care prices, capping the prices hospitals and other providers charge can help make insurance more affordable. Policymakers have an array of tools to do so, ranging from the Fair Pricing Act to the New York Health Act to the state’s former hospital price regulation system. Taking action now can help ensure small businesses have comprehensive and affordable coverage for years to come.