A Tax Plan for Statewide Universal Childcare

December 30, 2025 |

New York guarantees free education to children living in the state. Rapid development of free public schools in the second half of the nineteenth century culminated in an 1894 amendment to the New York State Constitution establishing a right to free schools for “all of the children of this state.” The public school system built in this period entitles New Yorkers aged five to twenty-one to free education. More recently, policymakers, including Governor Hochul and Mayor-elect Mamdani, have committed to finishing the project by extending universal free education and care to children under the age of five.1In this paper we will refer to a program of universal early childhood education (typically for three- and four-year-olds) and care (typically for children under the age of three) simply as “universal childcare.”

This care will take different forms—paid leave and daycare for younger children and preschool for older children—but must be truly universal: daylong, high-quality care that is an entitlement to the same extent as public schools. Just as no one would suggest that public education should be provided only to the poor, childcare must be publicly funded and provided for all New Yorkers regardless of household income.

The Fiscal Policy Institute estimates that a program of universal childcare throughout New York State, at average OECD uptake rates and at current pay levels, would cost $6.7 billion. A plan that raises childcare workers’ wages to the regional cost of living—$60,000 in New York City and $50,000 in the rest of the state—would total $7.9 billion. These costs are in addition to $4.9 billion in federal, state, and local funding already spent on care for children under five in New York State.

What would statewide universal childcare look like?

New York State already supports care for about one-quarter of the one million children under five living in the state. This care is provided by Paid Family Leave, the Child Care Assistance Program (CCAP, which provides vouchers for low- and moderate-income families), and pre-kindergarten. Universal childcare will build on these existing systems.

- For three- and four-year-olds. Free pre-kindergarten is currently universal for three- and four-year-olds in New York City. In the rest of the state, about two-thirds of four-year-olds and very few three-year-olds are enrolled in free preschool. The state must bring universal preschool for three- and four-year-olds to the entire state

- From six months to two years. For most children under three, the State must develop a system of publicly provided childcare that functions similarly to public schools, where parents have access to local, publicly funded care centers that are either free at the point of use or charge a fixed per day fee of $10 to $20. The State will need a transitional plan that begins by contracting existing childcare providers and eventually incorporates these providers into publicly run agencies. This system would supersede the current CCAP voucher system while retaining the minimum components necessary to continue receiving federal funding.

- For infants under six months. The first few months of an infant’s life are the most challenging for new parents and a time when parent-child bonding is of the utmost importance. The challenges of caring for infants under six months of age make it preferable for parents to have additional paid leave to be with their children. At twelve weeks per eligible adult, New York State Paid Family Leave is among the best paid time off policies in the U.S., but it remains comparatively limited by global standards.

Use of PFL is hindered by three features. First, single parents, who care for about one-quarter of young children, are only entitled to twelve weeks off and therefore lose out on the leave to which their co-parent might have been entitled. Second, fathers in New York have lower uptake and take shorter average leave than mothers. Third, much of the leave taken by fathers overlaps with that taken by mothers, shortening the total leave for each newborn.

Three changes would expand paid leave in the first year of life. First, broadening the entitlement from eligible workers to newborn children would entitle all parents—including single parents—to take a full leave allotment. Second, extending the duration of leave from twelve weeks per eligible adult to twenty-six weeks per child would give each parent more ability to take leave. Third, adopting a quota system requiring a portion of leave (for instance, six weeks) to be either taken by fathers (or co-parents) or forfeited, would encourage fathers to take more leave and encourage parents to stagger their leaves.2Gender quota systems are common to Nordic countries. A portion of leave (10–20% of total leave in most countries) is reserved for fathers to take. Any reserved paternal leave that is not taken is forfeited; the remaining weeks may be divided up as the parents wish. Reserved leave is not taken simultaneously with mothers. Rather, simultaneous leave is allowed for a fixed amount of time (generally two-to-six weeks) directly after birth. Evidence shows these systems increase father’s use of paid parental leave. See Yvette Lind, “Childcare Infrastructure in the Nordic Countries,” nordics.info, February 21, 2024, https://nordics.info/show/artikel/childcare-infrastructure-in-the-nordic-countries.

How to Pay for Universal Childcare

Universal childcare will require a significant expansion of the public sector—fiscally, to cover the costs of universal provision, and operationally, to provide care to hundreds of thousands of families statewide. Thus, the most important factor in phasing in a truly universal system is the availability of stable, recurring revenue that can support the full costs of the program. While New York State has a robust economy that can bear a higher tax burden, the art of financing childcare will be in selecting the right mix of broad-based taxes to fully fund the program in the long-term.

FPI looks to the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s financing for inspiration, as the MTA is funded by a diverse set of taxes that include a corporate tax surcharge, a payroll tax, a sales tax, petroleum taxes, and other taxes. The benefit of this financing strategy is that no particular tax base is overburdened and tax rates can be raised incrementally when new funding is needed without causing economic disruption or relying excessively on a single tax base.

Following this multiple-taxes model, FPI recommends a combination of progressive and broad-based taxes. Progressive tax increases on corporate profits and the incomes of the highest earners are necessary for the sake of fairness in an economic environment of growing inequality. At the same time, it is neither economically nor fiscally realistic to expect that the full $8 billion cost of statewide childcare can come from only the richest New Yorkers. For this reason, FPI also recommends a low-rate employee-side payroll tax on all wages as well as self-employment income. Not only is it fair for all New Yorkers to contribute to the cost of universal childcare—just as we all pay taxes for public schools—but a limited, broad-based contribution also tracks with the fundamental fiscal logic of the welfare state. Rather than thinking of taxing and spending in the welfare state as strictly redistributive from the rich to the poor and middle class, we should think of the welfare state as smoothing out income and consumption over lifetimes. That is, it is preferable for almost everyone to pay a small annual tax to fund universal childcare provision and avoid the cost spike of high tuition costs in the years in which they need childcare. One parent’s untenable burden of paying for childcare in the early years of life is transformed into a far smaller, more manageable burden spread over their own working life as well as the lifetimes of all other taxpayers. Thinking about welfare state spending in this way explains current government expenditures and shows the path toward financing new forms of public provision at scale.

One of the greatest risks in establishing a universal childcare program is overreliance on narrow revenue measures in the early stages—say, a small tax increase that pays for the program’s first-year costs but fails to provide enough revenue to allow it to fully phase in. Not only will costs rise as the program is phased in and uptake rises, but workers’ wages will also likely rise over time due to collective bargaining, and the program’s funding must be able to keep pace. If a sound and stable financing structure is not established at the origin of the program, we are unlikely to ever see a truly universal childcare program.

State and City Dimensions

FPI’s plan includes specific revenue measures enacted by New York City, so that the City can raise its own resources to fund its childcare program. The City income tax increase is similar to (but smaller than) the proposal put forth by Mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani, and it would serve to partly minimize the risk of annual state budget negotiations undercutting funding for the City’s program. This would also be consistent with the City’s current approach to early childhood funding, as New York City already spends $1.2 billion of its own revenue for universal preschool for three- and four-year-olds. This spending, together with CCAP and PFL, supports care for 150,000 children in New York City under age five—nearly two-thirds of the 240,000 children a universal system would be expected to support.

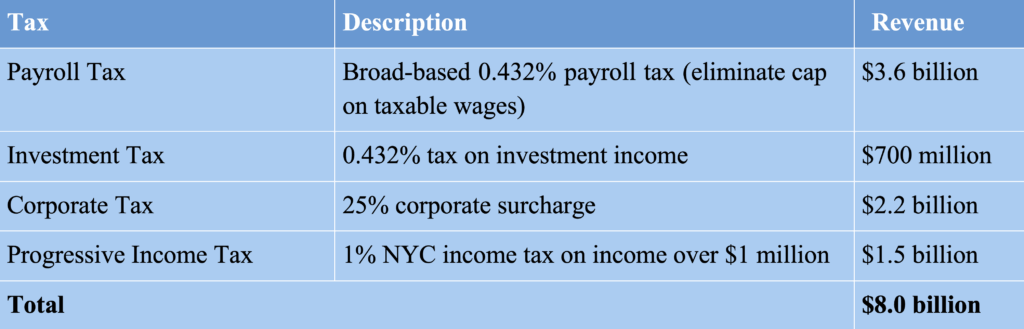

Table 1. New York State Childcare Financing Model

Tax Details

1. Payroll Tax: The first component of FPI’s recommended financing strategy is an employee-side payroll tax of 0.432 percent applied to all wages paid statewide as well as self-employment income.

New York already uses a payroll tax to fund its Paid Family Leave (PFL) program. The tax currently raises $962 million per year. Expanding the current tax by removing its regressivity and broadening the tax base could raise a total of $3.6 billion per year (including the revenue already raised by the PFL tax). The current tax is regressive, as it only applies—at a rate of 0.432 percent—to taxpayers’ first $95,300 of earnings. Because the tax is not imposed on any earnings over this threshold, taxpayers’ effective tax rate falls considerably: those earning $1 million pay an effective tax rate of 0.041 percent—one-tenth the rate paid by middle-income workers.

FPI’s proposed payroll tax makes three changes to the PFL tax: 1) removing the earnings cap such that the same tax rate applies to all earnings; 2) broadening the base to include all wages as well as self-employment income earned in the state; and 3) introducing progressivity by eliminating the tax for those earning less than $25,000 and halving the tax rate for those earning between $25,000 and $50,000.

The modest rate increase would minimally affect most upper-income workers. For instance, the payroll tax for a worker earning $140,000—twice the median for full-time, year-round workers in New York state—would rise from $412 per year to $605.3This proposal raises far more revenue than the current PFL payroll tax because it applies to all wages and self-employment income without an income cap and does not exclude any categories of worker. An expanded PFL should be readily accessible to all new parents and the application of the tax should be similarly broad.

2. Investment Income Tax: Payroll taxes apply to wage and salary earnings and exclude capital gains and other investment income. Because investment income is overwhelmingly earned by the very well-off, a fair payroll tax should be paired with a tax on non-wage investment income. This is the model of the Obamacare “Net Investment Income Tax,” which covers capital gains as well as rents, royalties, and other passive income for taxpayers with more than $250,000 in total income. This investment income tax should be paired with FPI’s proposed payroll tax and it should mirror that tax’s rate and brackets. Such a tax on investment income would raise $700 million per year.

3. Corporate Tax: To provide the MTA with a reliable source of funding, New York State currently levies a surcharge on its corporate profits tax (within the region serviced by the MTA). A childcare surcharge of 25 percent applied statewide would raise $2.2 billion per year. The corporate tax surcharge could also be set in functional terms to raise enough to cover a specified percentage of the program cost, rather than taxing a fixed percentage of corporate profits (for instance, it could be set at whatever rate is necessary to generate 27.5 percent of all required childcare revenue—the share accounted for in FPI’s modeling above).

4. NYC Income Tax: The New York City income tax is effectively flat, leaving room at the top of the income distribution for a higher tax rate. Increasing this rate by 1 percent for those earning more than $1 million would raise $1.5 billion per year. While the Governor has expressed unwillingness to raise state personal income taxes, she may recognize the electoral mandate for progressive revenue dedicated to childcare in New York City itself. This system would allow New York City greater control over its own childcare funding.

A Tax Plan for Statewide Universal Childcare

December 30, 2025 |

New York guarantees free education to children living in the state. Rapid development of free public schools in the second half of the nineteenth century culminated in an 1894 amendment to the New York State Constitution establishing a right to free schools for “all of the children of this state.” The public school system built in this period entitles New Yorkers aged five to twenty-one to free education. More recently, policymakers, including Governor Hochul and Mayor-elect Mamdani, have committed to finishing the project by extending universal free education and care to children under the age of five.1In this paper we will refer to a program of universal early childhood education (typically for three- and four-year-olds) and care (typically for children under the age of three) simply as “universal childcare.”

This care will take different forms—paid leave and daycare for younger children and preschool for older children—but must be truly universal: daylong, high-quality care that is an entitlement to the same extent as public schools. Just as no one would suggest that public education should be provided only to the poor, childcare must be publicly funded and provided for all New Yorkers regardless of household income.

The Fiscal Policy Institute estimates that a program of universal childcare throughout New York State, at average OECD uptake rates and at current pay levels, would cost $6.7 billion. A plan that raises childcare workers’ wages to the regional cost of living—$60,000 in New York City and $50,000 in the rest of the state—would total $7.9 billion. These costs are in addition to $4.9 billion in federal, state, and local funding already spent on care for children under five in New York State.

What would statewide universal childcare look like?

New York State already supports care for about one-quarter of the one million children under five living in the state. This care is provided by Paid Family Leave, the Child Care Assistance Program (CCAP, which provides vouchers for low- and moderate-income families), and pre-kindergarten. Universal childcare will build on these existing systems.

- For three- and four-year-olds. Free pre-kindergarten is currently universal for three- and four-year-olds in New York City. In the rest of the state, about two-thirds of four-year-olds and very few three-year-olds are enrolled in free preschool. The state must bring universal preschool for three- and four-year-olds to the entire state

- From six months to two years. For most children under three, the State must develop a system of publicly provided childcare that functions similarly to public schools, where parents have access to local, publicly funded care centers that are either free at the point of use or charge a fixed per day fee of $10 to $20. The State will need a transitional plan that begins by contracting existing childcare providers and eventually incorporates these providers into publicly run agencies. This system would supersede the current CCAP voucher system while retaining the minimum components necessary to continue receiving federal funding.

- For infants under six months. The first few months of an infant’s life are the most challenging for new parents and a time when parent-child bonding is of the utmost importance. The challenges of caring for infants under six months of age make it preferable for parents to have additional paid leave to be with their children. At twelve weeks per eligible adult, New York State Paid Family Leave is among the best paid time off policies in the U.S., but it remains comparatively limited by global standards.

Use of PFL is hindered by three features. First, single parents, who care for about one-quarter of young children, are only entitled to twelve weeks off and therefore lose out on the leave to which their co-parent might have been entitled. Second, fathers in New York have lower uptake and take shorter average leave than mothers. Third, much of the leave taken by fathers overlaps with that taken by mothers, shortening the total leave for each newborn.

Three changes would expand paid leave in the first year of life. First, broadening the entitlement from eligible workers to newborn children would entitle all parents—including single parents—to take a full leave allotment. Second, extending the duration of leave from twelve weeks per eligible adult to twenty-six weeks per child would give each parent more ability to take leave. Third, adopting a quota system requiring a portion of leave (for instance, six weeks) to be either taken by fathers (or co-parents) or forfeited, would encourage fathers to take more leave and encourage parents to stagger their leaves.2Gender quota systems are common to Nordic countries. A portion of leave (10–20% of total leave in most countries) is reserved for fathers to take. Any reserved paternal leave that is not taken is forfeited; the remaining weeks may be divided up as the parents wish. Reserved leave is not taken simultaneously with mothers. Rather, simultaneous leave is allowed for a fixed amount of time (generally two-to-six weeks) directly after birth. Evidence shows these systems increase father’s use of paid parental leave. See Yvette Lind, “Childcare Infrastructure in the Nordic Countries,” nordics.info, February 21, 2024, https://nordics.info/show/artikel/childcare-infrastructure-in-the-nordic-countries.

How to Pay for Universal Childcare

Universal childcare will require a significant expansion of the public sector—fiscally, to cover the costs of universal provision, and operationally, to provide care to hundreds of thousands of families statewide. Thus, the most important factor in phasing in a truly universal system is the availability of stable, recurring revenue that can support the full costs of the program. While New York State has a robust economy that can bear a higher tax burden, the art of financing childcare will be in selecting the right mix of broad-based taxes to fully fund the program in the long-term.

FPI looks to the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s financing for inspiration, as the MTA is funded by a diverse set of taxes that include a corporate tax surcharge, a payroll tax, a sales tax, petroleum taxes, and other taxes. The benefit of this financing strategy is that no particular tax base is overburdened and tax rates can be raised incrementally when new funding is needed without causing economic disruption or relying excessively on a single tax base.

Following this multiple-taxes model, FPI recommends a combination of progressive and broad-based taxes. Progressive tax increases on corporate profits and the incomes of the highest earners are necessary for the sake of fairness in an economic environment of growing inequality. At the same time, it is neither economically nor fiscally realistic to expect that the full $8 billion cost of statewide childcare can come from only the richest New Yorkers. For this reason, FPI also recommends a low-rate employee-side payroll tax on all wages as well as self-employment income. Not only is it fair for all New Yorkers to contribute to the cost of universal childcare—just as we all pay taxes for public schools—but a limited, broad-based contribution also tracks with the fundamental fiscal logic of the welfare state. Rather than thinking of taxing and spending in the welfare state as strictly redistributive from the rich to the poor and middle class, we should think of the welfare state as smoothing out income and consumption over lifetimes. That is, it is preferable for almost everyone to pay a small annual tax to fund universal childcare provision and avoid the cost spike of high tuition costs in the years in which they need childcare. One parent’s untenable burden of paying for childcare in the early years of life is transformed into a far smaller, more manageable burden spread over their own working life as well as the lifetimes of all other taxpayers. Thinking about welfare state spending in this way explains current government expenditures and shows the path toward financing new forms of public provision at scale.

One of the greatest risks in establishing a universal childcare program is overreliance on narrow revenue measures in the early stages—say, a small tax increase that pays for the program’s first-year costs but fails to provide enough revenue to allow it to fully phase in. Not only will costs rise as the program is phased in and uptake rises, but workers’ wages will also likely rise over time due to collective bargaining, and the program’s funding must be able to keep pace. If a sound and stable financing structure is not established at the origin of the program, we are unlikely to ever see a truly universal childcare program.

State and City Dimensions

FPI’s plan includes specific revenue measures enacted by New York City, so that the City can raise its own resources to fund its childcare program. The City income tax increase is similar to (but smaller than) the proposal put forth by Mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani, and it would serve to partly minimize the risk of annual state budget negotiations undercutting funding for the City’s program. This would also be consistent with the City’s current approach to early childhood funding, as New York City already spends $1.2 billion of its own revenue for universal preschool for three- and four-year-olds. This spending, together with CCAP and PFL, supports care for 150,000 children in New York City under age five—nearly two-thirds of the 240,000 children a universal system would be expected to support.

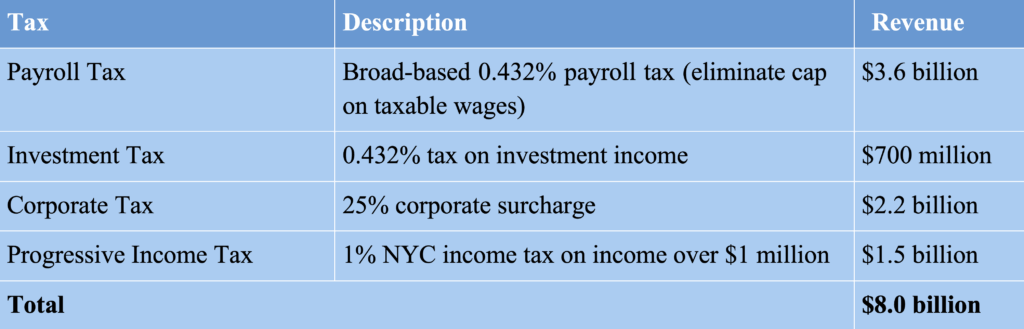

Table 1. New York State Childcare Financing Model

Tax Details

1. Payroll Tax: The first component of FPI’s recommended financing strategy is an employee-side payroll tax of 0.432 percent applied to all wages paid statewide as well as self-employment income.

New York already uses a payroll tax to fund its Paid Family Leave (PFL) program. The tax currently raises $962 million per year. Expanding the current tax by removing its regressivity and broadening the tax base could raise a total of $3.6 billion per year (including the revenue already raised by the PFL tax). The current tax is regressive, as it only applies—at a rate of 0.432 percent—to taxpayers’ first $95,300 of earnings. Because the tax is not imposed on any earnings over this threshold, taxpayers’ effective tax rate falls considerably: those earning $1 million pay an effective tax rate of 0.041 percent—one-tenth the rate paid by middle-income workers.

FPI’s proposed payroll tax makes three changes to the PFL tax: 1) removing the earnings cap such that the same tax rate applies to all earnings; 2) broadening the base to include all wages as well as self-employment income earned in the state; and 3) introducing progressivity by eliminating the tax for those earning less than $25,000 and halving the tax rate for those earning between $25,000 and $50,000.

The modest rate increase would minimally affect most upper-income workers. For instance, the payroll tax for a worker earning $140,000—twice the median for full-time, year-round workers in New York state—would rise from $412 per year to $605.3This proposal raises far more revenue than the current PFL payroll tax because it applies to all wages and self-employment income without an income cap and does not exclude any categories of worker. An expanded PFL should be readily accessible to all new parents and the application of the tax should be similarly broad.

2. Investment Income Tax: Payroll taxes apply to wage and salary earnings and exclude capital gains and other investment income. Because investment income is overwhelmingly earned by the very well-off, a fair payroll tax should be paired with a tax on non-wage investment income. This is the model of the Obamacare “Net Investment Income Tax,” which covers capital gains as well as rents, royalties, and other passive income for taxpayers with more than $250,000 in total income. This investment income tax should be paired with FPI’s proposed payroll tax and it should mirror that tax’s rate and brackets. Such a tax on investment income would raise $700 million per year.

3. Corporate Tax: To provide the MTA with a reliable source of funding, New York State currently levies a surcharge on its corporate profits tax (within the region serviced by the MTA). A childcare surcharge of 25 percent applied statewide would raise $2.2 billion per year. The corporate tax surcharge could also be set in functional terms to raise enough to cover a specified percentage of the program cost, rather than taxing a fixed percentage of corporate profits (for instance, it could be set at whatever rate is necessary to generate 27.5 percent of all required childcare revenue—the share accounted for in FPI’s modeling above).

4. NYC Income Tax: The New York City income tax is effectively flat, leaving room at the top of the income distribution for a higher tax rate. Increasing this rate by 1 percent for those earning more than $1 million would raise $1.5 billion per year. While the Governor has expressed unwillingness to raise state personal income taxes, she may recognize the electoral mandate for progressive revenue dedicated to childcare in New York City itself. This system would allow New York City greater control over its own childcare funding.