A Tax Plan for Universal Childcare in New York City

December 11, 2025 |

Mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani made universal childcare a central plank of his campaign platform, and once inaugurated he is widely expected to push for a deal in this year’s state budget to authorize new taxes to fund the program. While many policy experts have opined on the need for a universal program, little has been written about how it might practically be financed. But the single most decisive factor in whether New York City (or New York State) ends up with a truly universal childcare system is whether that system is supported by sustainable, recurring revenue that grows with the program over time.

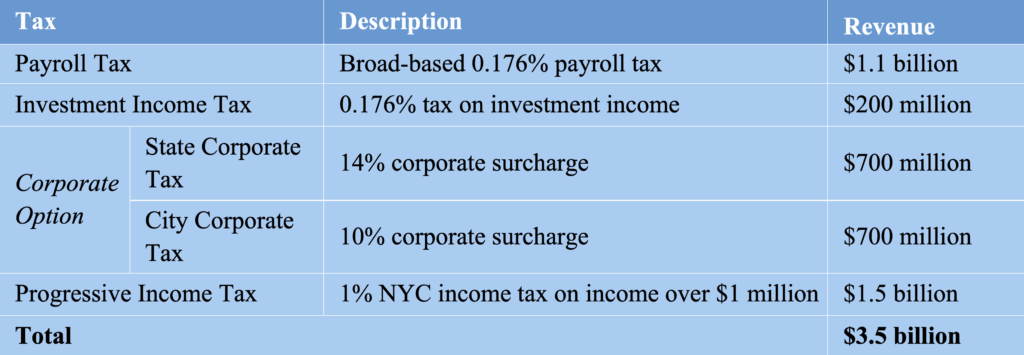

In New York City, FPI estimates that the new cost of providing universal care to children aged two and younger is $2.5 billion (at OECD average uptake rates and current compensation rates). If the City were to raise childcare worker wages to $60,000 (up from their statewide average of $38,000) using a City-run program, the cost would rise to approximately $3.5 billion. These incremental costs are proportionally lower for the City than the State because the City currently supports care for 150,000 children through a combination of paid family leave, child care vouchers, and UPK and 3-K—nearly two-thirds of the 240,000 children a universal system would be expected to support. Given relatively widespread agreement that current wages are too low, FPI assumes that wage increases will be part of any deal.

FPI recommends adopting a mix of taxes to finance universal childcare, following the multiple-taxes model that funds the MTA. A combination of progressive and broad-based taxes would allow revenue to grow with the program over time while ensuring stable and fair funding. In our view, one of the greatest risks when building a universal childcare program is overreliance on narrow revenue measures in the early stages. Such measures may be adequate to the program’s initial cost but will not scale up as the program phases in, uptake rises, and, most importantly, as workers’ wages increase. If the costs of financing the program are spread across multiple relatively large tax bases, it will be easier to ensure the revenue required for a fully universal program while staying within the bounds of economic and political feasibility.

Table 1. New York City Childcare Financing Model

Tax Recommendations

1. Payroll Tax: FPI recommends an employee-side payroll tax as one component of the funding mechanism. This tax would apply to all wages paid in the five boroughs, as well as self-employment income. Payroll taxes are a common financing mechanism for social welfare provision, as they operate on the principle that it is fair for all users of a program to shoulder some share of the costs. Most payroll taxes in the U.S., however, are poorly designed and only apply to a limited dollar amount of wages (e.g., the first $75,000 of earnings), making them highly regressive tax instruments. A low-rate payroll tax of 0.176 percent applied to all wages would require only modest contributions: a New Yorker earning $70,000—the median for full-time workers—would pay just $126 per year.

FPI’s payroll tax would also exempt the wages of workers earning less than $25,000 and reduce the tax rate by half for workers earning between $25,000 and $50,000.

2. Investment Income Tax: Payroll taxes only apply to wage and salary earnings, leaving income from capital gains and other passive sources untaxed. Because investment income is overwhelmingly earned by the very well-off, a payroll tax should be paired with a tax on non-wage investment income to maintain fairness in the tax system. This is the model of the Obamacare “Net Investment Income Tax,” which covers capital gains as well as rents, royalties, and other passive income. Like the Obamacare NIIT, FPI’s investment income tax would apply to taxpayers earning over $250,000 in ordinary income (at the payroll tax rate of 0.176 percent), raising $200 million per year.

3. Corporate Tax: New York State currently levies a surcharge on its corporate profits tax as a reliable funding source for the MTA. A similar corporate surcharge would be appropriate to pay for childcare, and it could be imposed at either the state or the city level. FPI models two different options for such dedicated surcharges: 1) a 14 percent surcharge on the State’s corporate tax, which we assume is directed to funding the City’s program, or 2) a 10 percent surcharge on the City’s corporate tax. Either option would raise approximately $700 million. The City often prefers to have control over its own revenue instruments so that the funding allocation is not up for debate each year in the state budget.

4. NYC Income Tax: The New York City income tax is a virtually flat 3.9 percent, leaving room at the upper levels of the income distribution for a higher tax rate. An income tax increase of 1 percentage point—imposed as a flat rate, not a marginal rate—on those earning over $1 million would currently raise $1.5 billion per year, contributing significantly to the program’s fiscal stability while maintaining fairness in the tax system. As a matter of public legitimacy, it will be important to pair a broad-based measure such as a payroll tax, which will affect almost all workers in the City, with a more sharply progressive tax on the highest earners.

A Tax Plan for Universal Childcare in New York City

December 11, 2025 |

Mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani made universal childcare a central plank of his campaign platform, and once inaugurated he is widely expected to push for a deal in this year’s state budget to authorize new taxes to fund the program. While many policy experts have opined on the need for a universal program, little has been written about how it might practically be financed. But the single most decisive factor in whether New York City (or New York State) ends up with a truly universal childcare system is whether that system is supported by sustainable, recurring revenue that grows with the program over time.

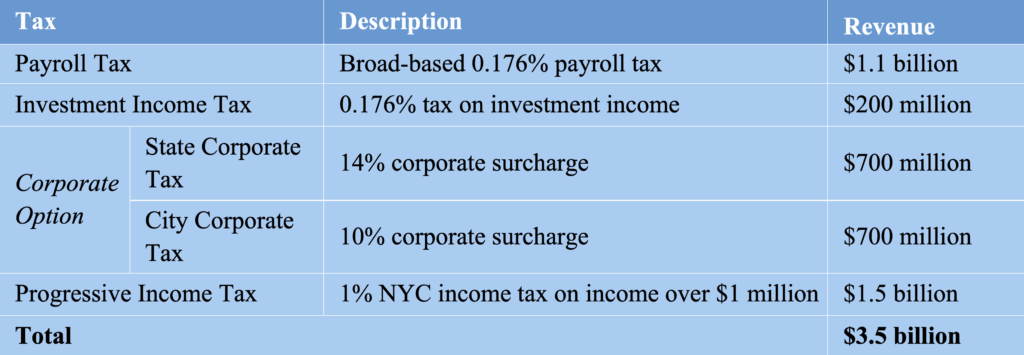

In New York City, FPI estimates that the new cost of providing universal care to children aged two and younger is $2.5 billion (at OECD average uptake rates and current compensation rates). If the City were to raise childcare worker wages to $60,000 (up from their statewide average of $38,000) using a City-run program, the cost would rise to approximately $3.5 billion. These incremental costs are proportionally lower for the City than the State because the City currently supports care for 150,000 children through a combination of paid family leave, child care vouchers, and UPK and 3-K—nearly two-thirds of the 240,000 children a universal system would be expected to support. Given relatively widespread agreement that current wages are too low, FPI assumes that wage increases will be part of any deal.

FPI recommends adopting a mix of taxes to finance universal childcare, following the multiple-taxes model that funds the MTA. A combination of progressive and broad-based taxes would allow revenue to grow with the program over time while ensuring stable and fair funding. In our view, one of the greatest risks when building a universal childcare program is overreliance on narrow revenue measures in the early stages. Such measures may be adequate to the program’s initial cost but will not scale up as the program phases in, uptake rises, and, most importantly, as workers’ wages increase. If the costs of financing the program are spread across multiple relatively large tax bases, it will be easier to ensure the revenue required for a fully universal program while staying within the bounds of economic and political feasibility.

Table 1. New York City Childcare Financing Model

Tax Recommendations

1. Payroll Tax: FPI recommends an employee-side payroll tax as one component of the funding mechanism. This tax would apply to all wages paid in the five boroughs, as well as self-employment income. Payroll taxes are a common financing mechanism for social welfare provision, as they operate on the principle that it is fair for all users of a program to shoulder some share of the costs. Most payroll taxes in the U.S., however, are poorly designed and only apply to a limited dollar amount of wages (e.g., the first $75,000 of earnings), making them highly regressive tax instruments. A low-rate payroll tax of 0.176 percent applied to all wages would require only modest contributions: a New Yorker earning $70,000—the median for full-time workers—would pay just $126 per year.

FPI’s payroll tax would also exempt the wages of workers earning less than $25,000 and reduce the tax rate by half for workers earning between $25,000 and $50,000.

2. Investment Income Tax: Payroll taxes only apply to wage and salary earnings, leaving income from capital gains and other passive sources untaxed. Because investment income is overwhelmingly earned by the very well-off, a payroll tax should be paired with a tax on non-wage investment income to maintain fairness in the tax system. This is the model of the Obamacare “Net Investment Income Tax,” which covers capital gains as well as rents, royalties, and other passive income. Like the Obamacare NIIT, FPI’s investment income tax would apply to taxpayers earning over $250,000 in ordinary income (at the payroll tax rate of 0.176 percent), raising $200 million per year.

3. Corporate Tax: New York State currently levies a surcharge on its corporate profits tax as a reliable funding source for the MTA. A similar corporate surcharge would be appropriate to pay for childcare, and it could be imposed at either the state or the city level. FPI models two different options for such dedicated surcharges: 1) a 14 percent surcharge on the State’s corporate tax, which we assume is directed to funding the City’s program, or 2) a 10 percent surcharge on the City’s corporate tax. Either option would raise approximately $700 million. The City often prefers to have control over its own revenue instruments so that the funding allocation is not up for debate each year in the state budget.

4. NYC Income Tax: The New York City income tax is a virtually flat 3.9 percent, leaving room at the upper levels of the income distribution for a higher tax rate. An income tax increase of 1 percentage point—imposed as a flat rate, not a marginal rate—on those earning over $1 million would currently raise $1.5 billion per year, contributing significantly to the program’s fiscal stability while maintaining fairness in the tax system. As a matter of public legitimacy, it will be important to pair a broad-based measure such as a payroll tax, which will affect almost all workers in the City, with a more sharply progressive tax on the highest earners.