Strange Accounting: Understanding the Growth in New York’s Medicaid Spending

February 15, 2025 |

State estimates Medicaid growth at 13.7 percent—but more comprehensive measure indicates only 3.7 percent growth

Executive Summary

The Executive Budget projects total state-share Medicaid growth of 17.1 percent, or $6.4 billion – an extraordinary rate of growth. Department of Health Medicaid spending alone is projected to rise by $4.3 billion or 13.7 percent. Yet enrollment has declined sharply over the past 18 months and is projected to remain virtually flat this year. What explains this dramatic divergence between spending and enrollment?

The Executive Budget figures on spending growth are in fact somewhat misleading. It would be more accurate to estimate growth of state-share Medicaid spending at 3.7 percent, not 13.7 percent, for several reasons:

- The Executive Budget focuses on state-share Medicaid spending. Total Medicaid spending, including federal and local funds, is projected to rise by 7.2 percent – a significant increase, to be sure, but far less than state-share spending. The dramatic increase reported in the Executive Budget largely reflects a decline in federal support for New York’s Medicaid program, rather than runaway growth in the underlying programs.

- The State’s reported $4.3 billion growth in Department of Health Medicaid spending includes billions of dollars in state-share MCO tax-related spending. But $1.2 billion of this state spending (and approximately $2.6 billion in all-funds Medicaid spending) merely reimburses Medicaid MCOs for their share of the tax. It does not cost the state a dime and does not reflect increases in Medicaid spending or utilization. Adjusting for the MCO tax, all-funds growth is just 4.7 percent.

- Spending in fiscal year 2025 is artificially lowered by a one-time $951 million repayment the State expects to receive from certain safety-net hospitals. This artificially low figure for fiscal year 2025 spending exaggerates expected spending growth in fiscal year 2026. Adjusting for this one-time expense gives all-funds program growth of just 3.7 percent. State-share spending is projected to increase more rapidly, but this increase is driven primarily by the end of federal pandemic assistance and other federal shifts, not program growth as such.

To be sure, 3.7 percent growth in the state’s single largest budget item is certainly fiscally significant, but far less concerning than the 17.1 percent increase in state-share Medicaid, or 13.7 percent increase in state-share Department of Health Medicaid, emphasized in the Executive Budget. Policymakers considering changes to the Medicaid program should focus on true program growth, not short-term shifts in funding sources and accounting choices, when considering Medicaid reforms.

Introduction

Medicaid spending is once again front and center in the debate over New York’s fiscal trajectory, with the recently released Executive Budget projecting a 17.1 percent increase in state-share Medicaid spending in FY 2026—an increase of $6.4 billion from the current fiscal year. This increase follows a 5.1 percent increase in FY 2025 state-share spending from FY 2024—well above the state’s initial projection at the beginning of FY 2025 that state spending would rise by just 2.1%.

This increase is quite surprising, since Medicaid enrollment has actually fallen dramatically in the past two years—from just over 8 million in June of 2023 to just under 7 million in November of 2024, a 12 percent drop. Enrollment in New York’s largest Medicaid program, Mainstream Managed Care, which provides comprehensive health insurance to low-income New Yorkers, has fallen even more dramatically—from 5.7 million to 4.5 million, a drop of 20.5%. The latter program remains slightly above its pre-pandemic level of 4.1 million in January 2020, but enrollment continues to drop at a rate of tens of thousands of enrollees per month. Furthermore, the Executive Budget projects virtually no enrollment increase in FY 2026: Enrollment is expected to go up by just 30,000, an increase of just 0.4 percent.

To be sure, enrollment in the state’s expensive managed long-term care programs continues to increase—it was up by nearly 41,000 members or 12 percent between December 2023 and December 2024, to a total of nearly 376,000 enrollees—but even if enrollment continues to rise at that rate, the long-term care programs will add just 45,000 new enrollees next year. One struggles to understand how such a small increase can drive a 17 percent increase in spending on the entirety of Medicaid.

Why is the governor projecting an extraordinary increase in state-share Medicaid spending—one which the Executive Budget itself describes as “unsustainable”—even as enrollment is flat or falling? To understand these projections, we must take a detour through the sometimes murky world of New York State Medicaid accounting.

What do we mean by Medicaid spending?

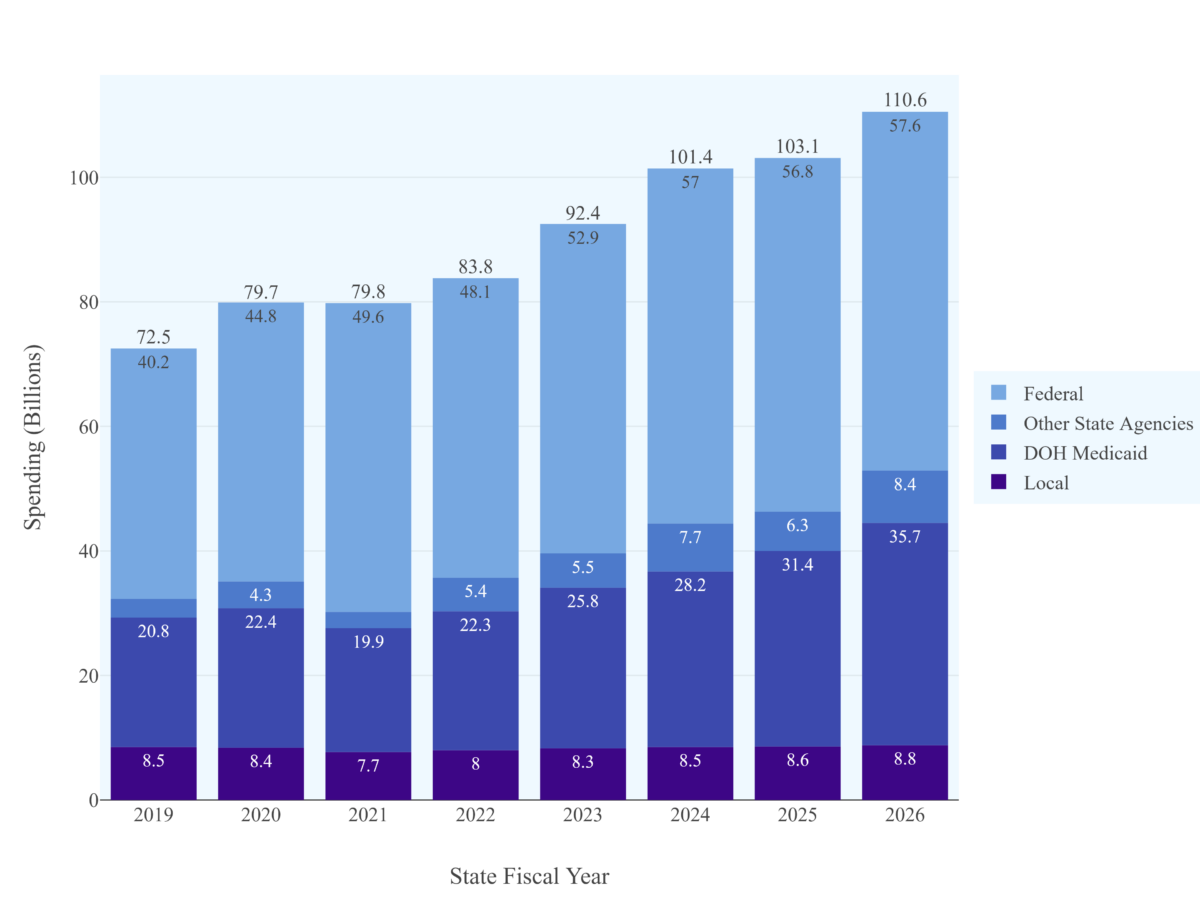

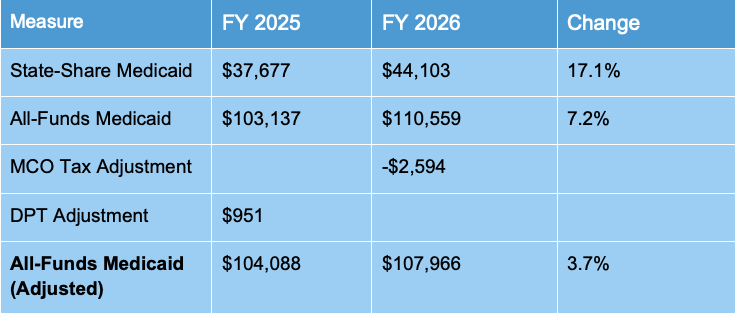

In New York, Medicaid is jointly funded, by local governments, the state, and the federal government. (See Figure 1.) The local share of Medicaid spending has been capped for the past decade and is currently around $8.6 billion. In FY 2025, the total state share is projected to be $37.7 billion, while the federal government will kick in $56.8 billion, for total spending of $103.1 billion. (These figures exclude funding for the Essential Plan, a separate program fully funded by the federal government.)

The vast majority of this funding goes to programs administered by the Department of Health which provide health insurance and long-term care to low-income New Yorkers. These DOH programs are what most policymakers mean when they refer to the Medicaid program without further specification, and are sometimes referred to as “DOH Medicaid.” A much smaller portion of Medicaid funding goes to other state agencies that administer healthcare programs – primarily mental health-related agencies, but also the Department of Education, foster services programs and the Department of Corrections.

Figure 1: Medicaid expenditure by source of funds and state agency, 2019-2026.

Note: Fiscal Years 2019-2024 reflect actual spending drawn from financial plan mid-year updates, while Fiscal Years 2025 and 2026 are projections drawn from the Fiscal Year 2026 Executive Budget Financial Plan. Federal share excludes Essential Plan funding. Local share funding for 2023 is estimated.

As mentioned above, “DOH (Department of Health) Medicaid” is New York’s largest Medicaid program and generates the most controversy. That’s why budgetary debate tends to focus on increases in DOH Medicaid. For example, when Governor Hochul pointed out in her budget address that Medicaid spending had grown by 14 percent, she was referring to growth in DOH Medicaid, which is projected to rise from $31.4 billion in the current fiscal year to $35.7 billion in FY 2026.

Unfortunately, it is impossible to reliably track Medicaid spending using the state’s “DOH Medicaid” figures, since the state has repeatedly and arbitrarily shifted spending between DOH Medicaid and Other State Agencies (OSA) Medicaid to avoid breaching the Medicaid Global Cap.[1] (This is why we see dramatic swings in OSA Medicaid from year to year; these swings do not reflect real changes in spending but rather accounting reclassifications.) Given the lack of figures for DOH Medicaid that are reliably comparable from year to year, in this piece we will focus on total state-share Medicaid funding.

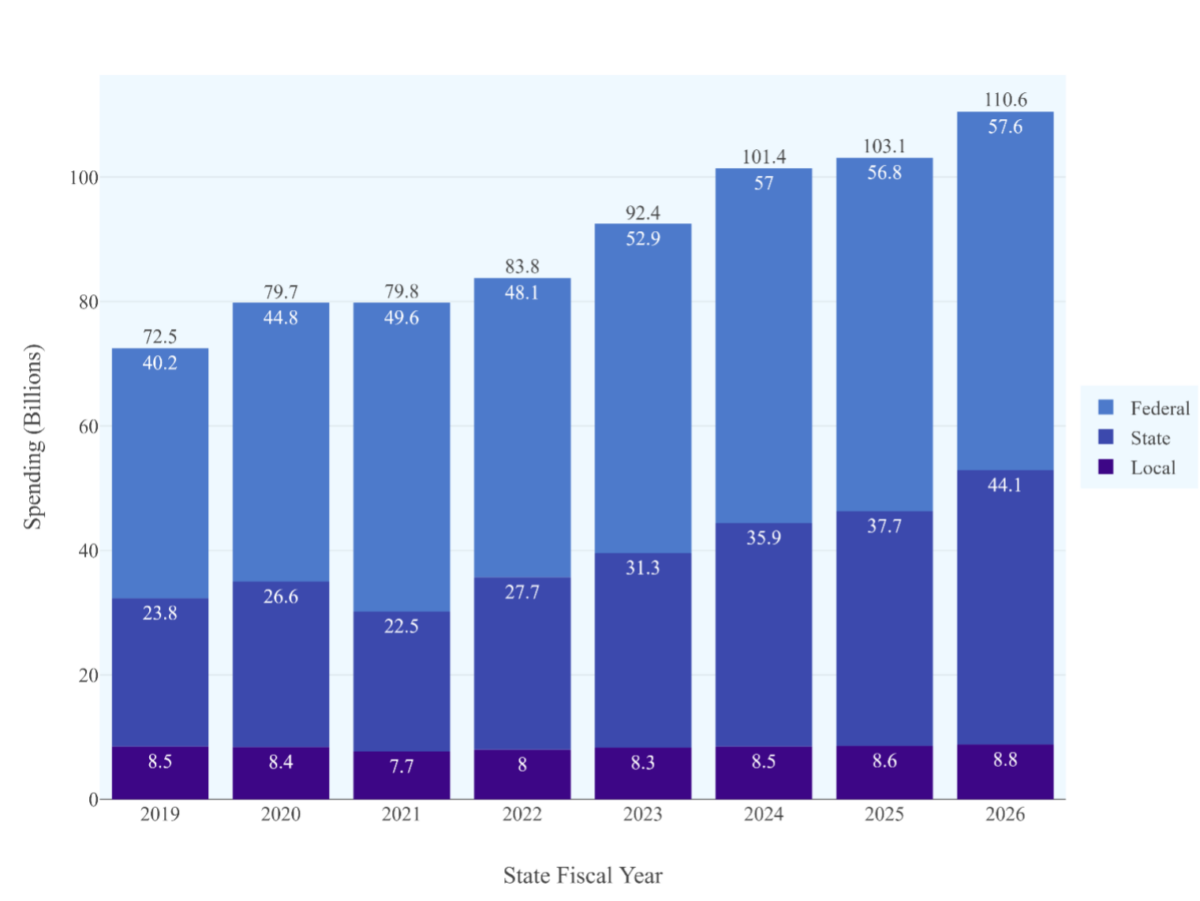

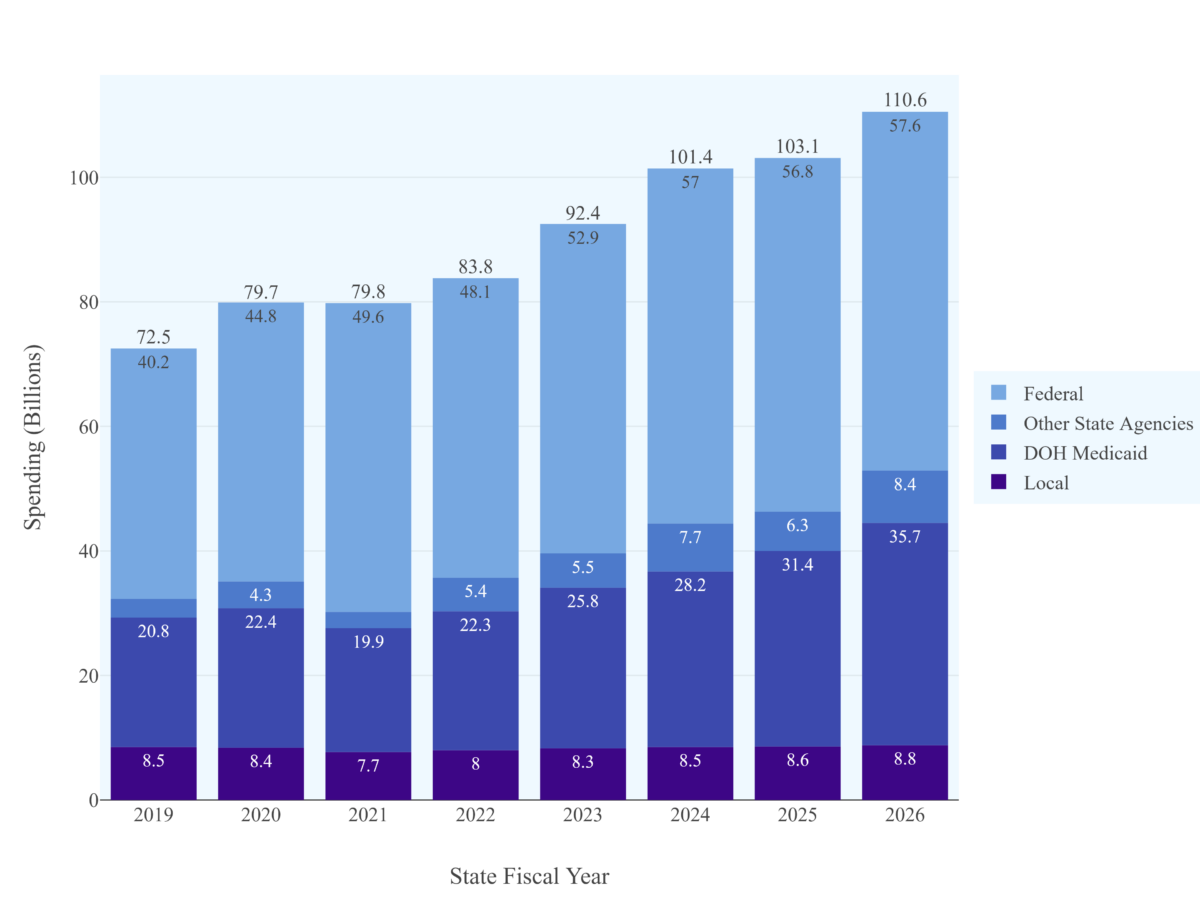

Figure 2: Medicaid expenditure by source of funds, 2019-2026.

Note: Fiscal Years 2019-2024 reflect actual spending drawn from financial plan mid-year updates, while Fiscal Years 2025 and 2026 are projections drawn from the Fiscal Year 2026 Executive Budget Financial Plan. Federal share excludes Essential Plan funding. Local share funding for 2023 is estimated.

Medicaid Program Growth has Moderated—but Federal Support has Diminished

Combining all state-share Medicaid spending, we see a truly dramatic leap in state spending—from a projected $37.7 billion in FY 2025 to $44.1 billion in FY 2026, a 17% increase in just one year.

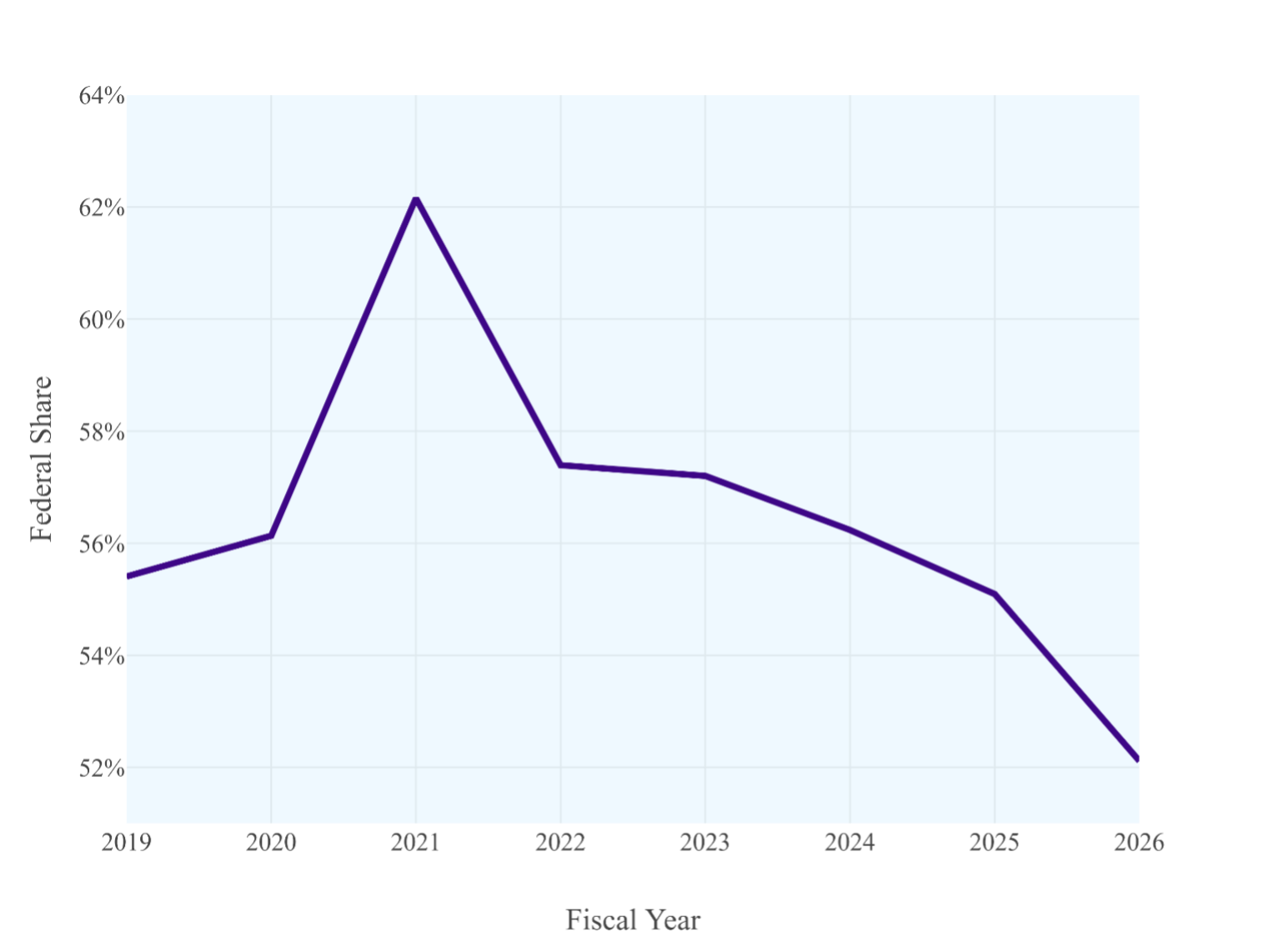

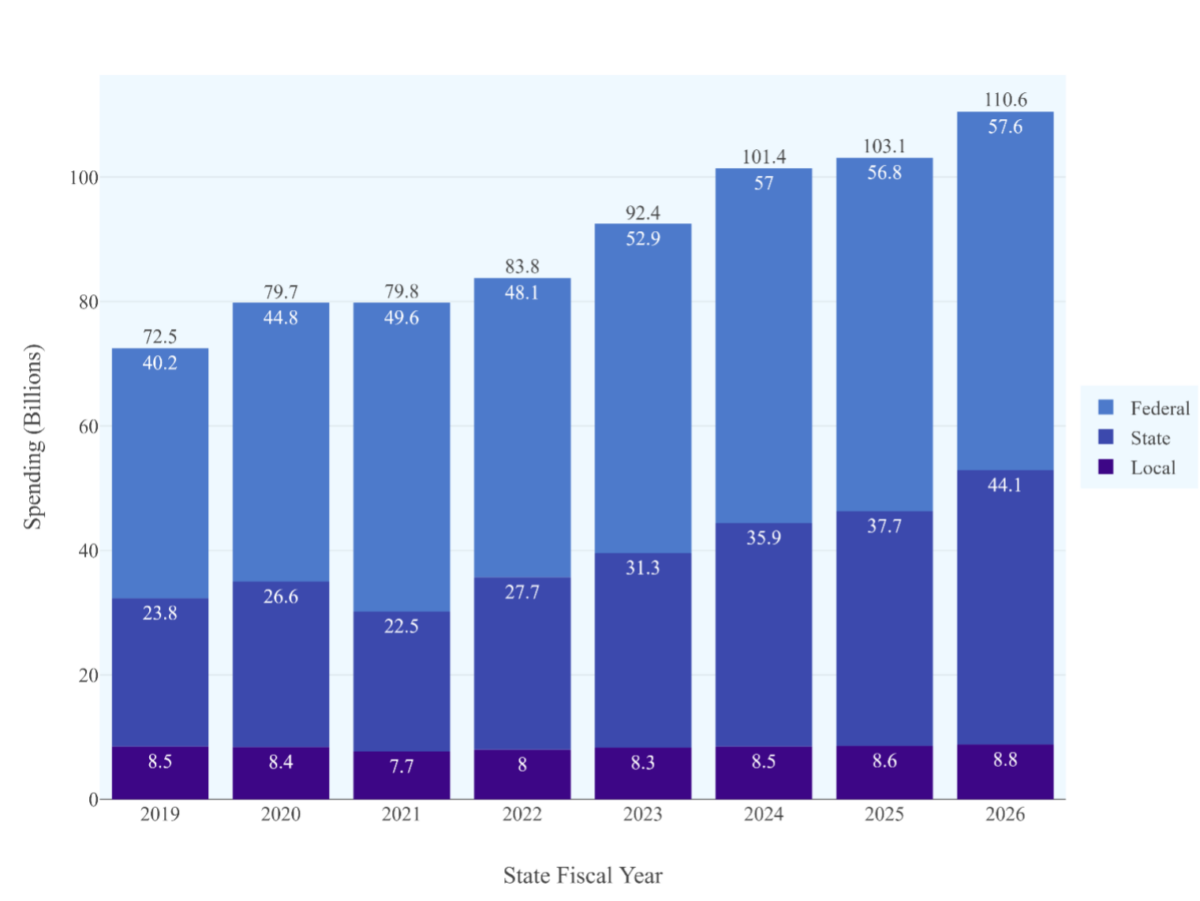

But this increase in state-share spending is not driven by out-of-control program growth. All-funds Medicaid spending is projected to grow far more slowly, by just 7.1%, after growing by just 1.7 percent in FY25. State-share spending is growing primarily because federal support has declined. The federal share of Medicaid, which hovered at 55 percent in the years before 2020, peaked at 60% at the height of federal pandemic relief before falling to 52% in FY 2026.

To put those figures in perspective, if the federal government’s share of Medicaid spending had stayed constant at FY 2024 levels, NYS state-share Medicaid spending would be $1.2 billion lower in FY 2025 and $4.7 billion lower in FY 2026 than is currently projected. More than half of the increase in state-share Medicaid spending is driven by decreased federal support.

Figure 3: Medicaid expenditure by source of funds, 2019-2026.

Note: FPI calculation based on DOB data.

The reduction in federal Medicaid funding (from extremely high levels in FY 2021-22) is a fiscal reality the state must address. But this reduction does not reflect long-term trends in Medicaid enrollment or utilization.

What explains the decrease in federal-share spending in FY 2026? While the Executive Budget Financial Plan does not provide much detail on this issue, two causes seem to be at work. In FY 2025, the state received the final tranche of enhanced federal matching funds from the American Rescue Plan, a total of $764 million in federal funds which will be replaced by state dollars in FY 2026. In addition, the Executive Budget appears to assume that New York’s allotment of federal Disproportionate Share Hospital funding will be reduced, pursuant to a long-deferred provision of the Affordable Care Act, which will result in a reduction of $1.4 billion in federal spending.[2]

Accounting for the MCO Tax

A major feature of the FY 2026 state budget is implementation of the MCO tax, a new provider tax levied on Medicaid and Essential Plan MCOs. I discussed the MCO tax in a policy brief last year, but will briefly review it here.

The MCO tax is a way of drawing down increased federal Medicaid funding. Schematically, the way it will work is that the state will tax Medicaid and Essential Plan MCOs and then spend the resulting revenue, plus an additional federal match. So, for example, the state could levy a $100 tax on Medicaid MCOs and pay the MCOs back $50 in state Medicaid funds plus a $50 federal match. The MCOs would then be made whole, but the state would retain $50, which it could spend on other Medicaid program areas, receiving an additional federal match. In the aggregate, the state would be taking $100 from the MCOs, paying them back $100, and receiving a $100 federal match – effectively generating $100 in additional federal Medicaid spending at no cost to the state.

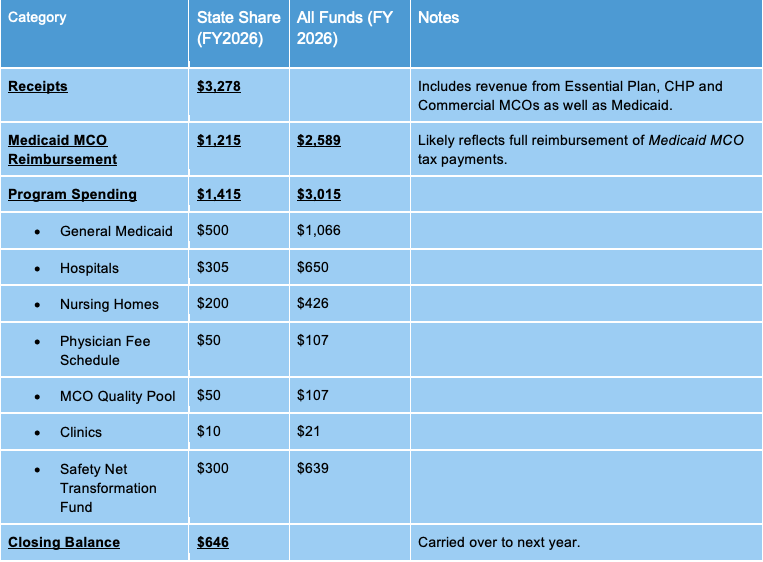

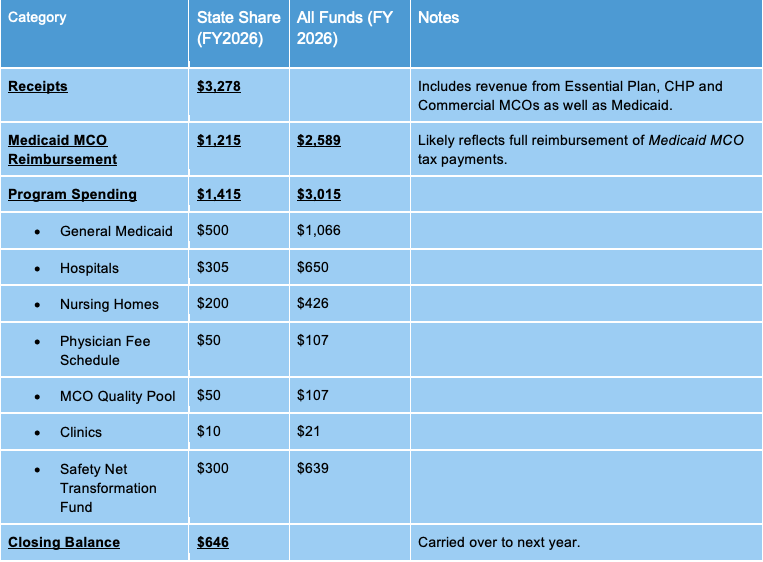

The state recently won federal approval for an MCO tax structured like this, and the Executive Budget provides details on how it will work. The state will receive $3.3 billion in taxes from Medicaid, CHP and Essential Plan MCOs. It will pay the Medicaid MCOs back for their share of the tax, using $1.2 billion in state funds and approximately $2.6 billion in federal funds.[3] This leaves the state with $2.1 billion in state dollars, of which it will spend $1.4 billion on FY 2026 Medicaid and reserve $646 million for future years. (See Table 1.)

Table 1. MCO Tax Spending (Millions)

Note: FPI calculation based on DOB data.

How does this financial maneuver impact Medicaid spending? The Executive Budget accounts for it as a $2.6 billion net increase in state-share Medicaid spending in FY 2026 — $1.2 billion in MCO reimbursement and $1.4 billion in other spending. This new $2.6 billion represents a large share of the overall $4.3 billion increase in state-share DOH Medicaid spending.

I would argue that this is quite misleading. Certainly, the $1.4 billion in program spending represents real growth in Medicaid costs (largely due to provider rate increases). But the $1.2 billion the state spends to reimburse MCOs does not reflect growth in Medicaid; no extra services are provided, no new enrollees are served, and no providers are paid more due to this spending. It is simply one side of a wash transaction: The MCOs pay the state, and the state pays the MCOs. The two payments simply cancel out.

It may be easiest to recognize this by considering a common criticism of the MCO tax. Many skeptics are concerned that the federal government may someday withdraw approval for the MCO tax, creating a “fiscal cliff” as the state is forced to make up lost MCO tax revenue. That is a reasonable fear when it comes to the $1.4 billion in program spending – if the MCO tax no longer pays for it, then the state will have to find another source of revenue or cut rates. But it is most certainly not true for the $1.2 billion in MCO tax reimbursement. If the federal government withdraws approval for the tax structure, then the state will stop collecting the tax and stop reimbursing the MCOs for the tax, leaving the MCOs no worse off than they are now.

In short, the $1.2 billion state share and $2.6 billion all-funds increase in Medicaid spending due solely to MCO reimbursement is illusory. Whatever one may think of the MCO tax as a whole, this aspect of it does not reflect real program growth.[4]

Classifying this spending appropriately brings state-share Medicaid spending down by $1.2 billion and all-funds Medicaid spending growth down by $2.6 billion. With this adjustment, all-funds Medicaid spending in FY 2026 is not $110.6 billion but $108 billion – and all-funds spending growth is not 7.2 percent but 4.7 percent.

The DPT Recoupment Saga

Finally, the Executive Budget’s account of Medicaid growth is affected by a one-time blip in Medicaid spending: The “Directed Payment Template recoupment,” the repayment of a large loan the State made to financially distressed hospitals in the period from FY 2022 to FY 2024.

Here’s the background: The Directed Payment Template is a Medicaid program to provide support for safety-net hospitals. The program was set to begin in FY 2022, but delays in federal approval meant that federal funding wasn’t available in time. To avoid burdening safety-net hospitals, the State loaned them the money, with the expectation that hospitals would pay the state back once they received federal funds. However, for unclear reasons not all of this money has been paid back.

The state accounted for this loan by recording an extra $915 million in Medicaid spending in fiscal year 2024 (reflecting the cost of the loan) and an offsetting negative-$915 million payment in fiscal year 2025 (reflecting the expectation that the loan would be repaid). This has the effect of artificially lowering fiscal year 2025 Medicaid spending: In fact, state-share program spending was $38.6 billion, but the state reported it at $37.7 billion to reflect the repayment of the loan.

It is not clear why the repayment has been delayed, or when repayment might occur. But the effect of accounting for it as negative spending in FY 2025 is to exaggerate spending growth in FY 2026.

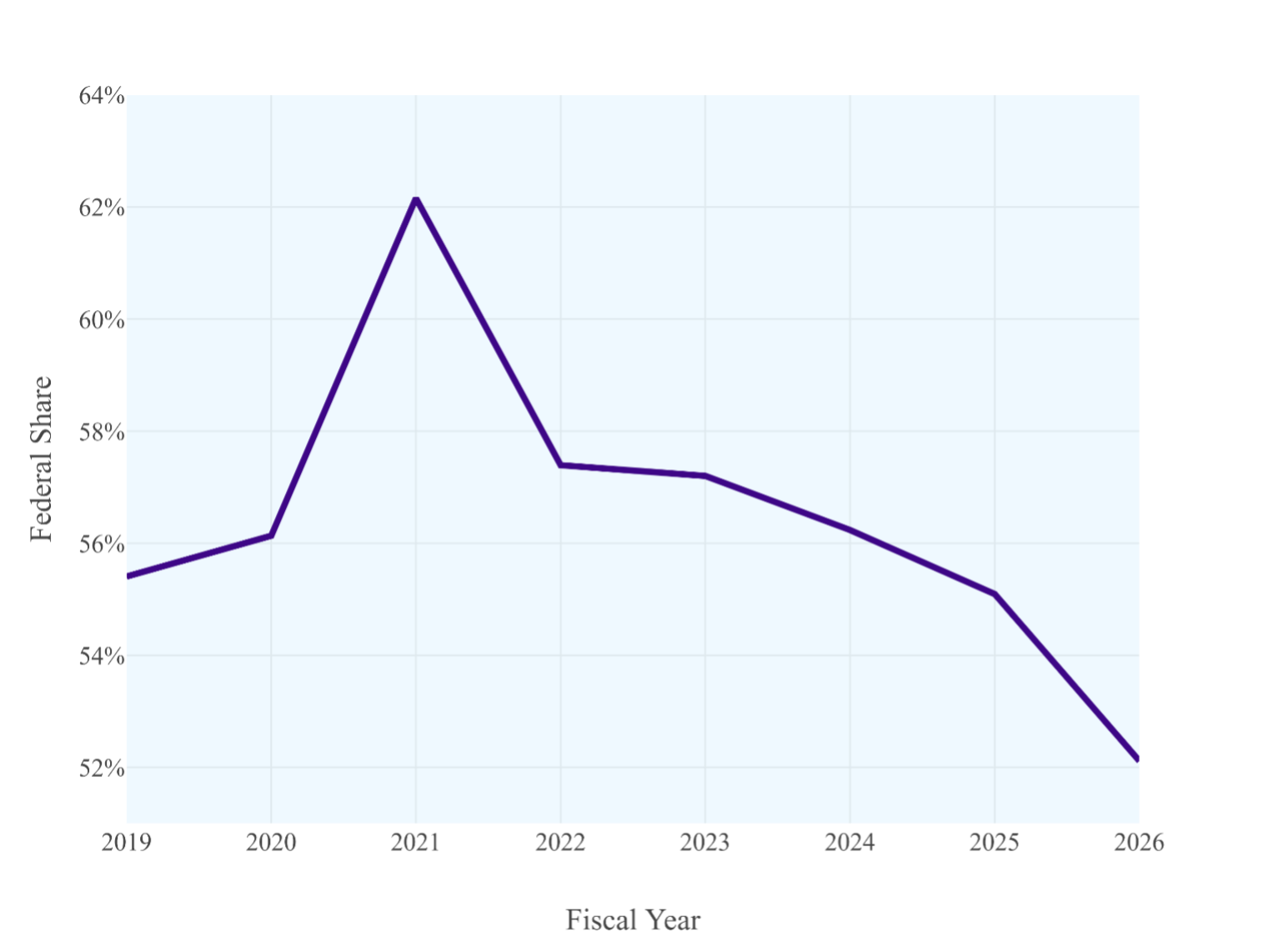

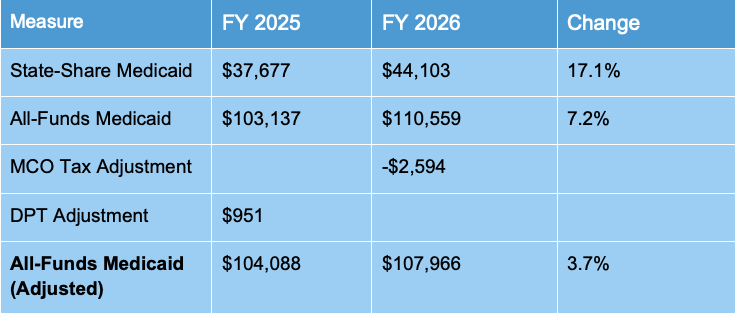

Summary

Putting all this together gives a very different picture of Medicaid spending growth than was presented in the executive budget: All-funds Medicaid spending on core programs is growing by just 3.7%. This compares favorably with private-sector projections that healthcare spending may increase by as much as 8% in 2025.[5]

Table 2: Adjusted All-Funds Medicaid Spending (Millions)

Conclusion: In Evaluating Medicaid Costs, Focus on the Program

Medicaid is a complex program – it is jointly funded by the state and federal governments, its spending is shaped by enrollment, utilization and provider rates, and in recent years it has been subject to rapid changes in both federal policy and economic conditions. All these variables can distort our view of total program spending. For this reason, it is important to separate shifts in the source of funds for Medicaid spending from shifts in the actual spending, and to separate one-time accounting changes from long-term trends in enrollment, utilization and provider rates.

Failure to distinguish these issues can seriously distort our understanding of how the Medicaid program is evolving. For example, much recent coverage of the Medicaid budget has argued that the program is experiencing spiraling spending growth driven by high long-term care spending and utilization. In fact, as we have seen, Medicaid spending growth is projected to be quite modest this year, and reported dramatic increases in spending are driven largely by accounting issues and decreased federal funding.

To be sure, state-share spending is important, even if it reflects reduced federal support rather than real program growth. Even adjusting for MCO reimbursement and one-time hospital payments, state-share all-agency Medicaid spending is expected to grow by $4.3 billion in FY 2026 due to decreased federal support. If federal policy remains stable then this is likely to be a one-time increase, but if the Trump administration cuts Medicaid at the federal level, then state policymakers will need to consider spending cuts or new sources of revenue, even if program growth remains modest.

Even so, understanding why state Medicaid costs are rising will be critical. If New York’s Medicaid program really were growing at an annualized rate of 17.1 percent at a time of flat enrollment, then the program would urgently require dramatic reform, regardless of federal policy. But as we have seen, spending is rising at a rate of less than 4 percent – far from unreasonable for a program that provides the sole source of long-term care coverage in a state with an aging population. Medicaid spending is growing, but it is not out of control or unsustainable, and policymakers should approach calls for cuts with caution.

Sources

[1] The state is legally required to keep DOH Medicaid spending beneath a set level (the DOH Global Cap). In recent years it has managed this by repeatedly reclassifying DOH Medicaid spending as Mental Hygiene spending, primarily through an accounting mechanism known as the Mental Hygiene Stabilization Fund. In the FY 2026 Executive Budget the state announced a permanent reclassification of $2.3 billion in spending from the Health line to the Mental Hygiene line.

[2] Even accounting for these figures, a 52 percent effective FMAP seems remarkably low. New York’s overall FMAP is 50%, but it receives higher match rates for special populations and services, such as the ACE New Adult Group (90% FMAP) and Community First Choice Option services (56% FMAP). These categories would be expected to raise the overall FMAP above 52 percent. Why, then, is the real figure so low? I suspect that the figure reflects substantial categories of state funding which receive no federal match at all, such as for Medicaid coverage of some categories of undocumented immigrants and unmatched aid to financially distressed providers.

[3] I estimate an effective FMAP on MCO Tax spending of 53.1 percent, using the FY 2026 Executive Budget figures for MCO tax-related state-share spending ($2.632 billion) and all-funds impact ($2.977 billion).

[4] Readers may wonder why the MCO tax has any impact at all on state-share spending – if the whole exercise is just a maneuver to generate more federal reimbursement, shouldn’t it simply increase the federal share of Medicaid, leaving state-share spending unchanged? But this is not quite the right way to think about it. The $3.278 billion in taxes paid by the MCOs is state tax revenue, no different from sales tax.

[5] https://www.pwc.com/us/en/industries/health-industries/library/behind-the-numbers.html

Strange Accounting: Understanding the Growth in New York’s Medicaid Spending

February 15, 2025 |

State estimates Medicaid growth at 13.7 percent—but more comprehensive measure indicates only 3.7 percent growth

Executive Summary

The Executive Budget projects total state-share Medicaid growth of 17.1 percent, or $6.4 billion – an extraordinary rate of growth. Department of Health Medicaid spending alone is projected to rise by $4.3 billion or 13.7 percent. Yet enrollment has declined sharply over the past 18 months and is projected to remain virtually flat this year. What explains this dramatic divergence between spending and enrollment?

The Executive Budget figures on spending growth are in fact somewhat misleading. It would be more accurate to estimate growth of state-share Medicaid spending at 3.7 percent, not 13.7 percent, for several reasons:

- The Executive Budget focuses on state-share Medicaid spending. Total Medicaid spending, including federal and local funds, is projected to rise by 7.2 percent – a significant increase, to be sure, but far less than state-share spending. The dramatic increase reported in the Executive Budget largely reflects a decline in federal support for New York’s Medicaid program, rather than runaway growth in the underlying programs.

- The State’s reported $4.3 billion growth in Department of Health Medicaid spending includes billions of dollars in state-share MCO tax-related spending. But $1.2 billion of this state spending (and approximately $2.6 billion in all-funds Medicaid spending) merely reimburses Medicaid MCOs for their share of the tax. It does not cost the state a dime and does not reflect increases in Medicaid spending or utilization. Adjusting for the MCO tax, all-funds growth is just 4.7 percent.

- Spending in fiscal year 2025 is artificially lowered by a one-time $951 million repayment the State expects to receive from certain safety-net hospitals. This artificially low figure for fiscal year 2025 spending exaggerates expected spending growth in fiscal year 2026. Adjusting for this one-time expense gives all-funds program growth of just 3.7 percent. State-share spending is projected to increase more rapidly, but this increase is driven primarily by the end of federal pandemic assistance and other federal shifts, not program growth as such.

To be sure, 3.7 percent growth in the state’s single largest budget item is certainly fiscally significant, but far less concerning than the 17.1 percent increase in state-share Medicaid, or 13.7 percent increase in state-share Department of Health Medicaid, emphasized in the Executive Budget. Policymakers considering changes to the Medicaid program should focus on true program growth, not short-term shifts in funding sources and accounting choices, when considering Medicaid reforms.

Introduction

Medicaid spending is once again front and center in the debate over New York’s fiscal trajectory, with the recently released Executive Budget projecting a 17.1 percent increase in state-share Medicaid spending in FY 2026—an increase of $6.4 billion from the current fiscal year. This increase follows a 5.1 percent increase in FY 2025 state-share spending from FY 2024—well above the state’s initial projection at the beginning of FY 2025 that state spending would rise by just 2.1%.

This increase is quite surprising, since Medicaid enrollment has actually fallen dramatically in the past two years—from just over 8 million in June of 2023 to just under 7 million in November of 2024, a 12 percent drop. Enrollment in New York’s largest Medicaid program, Mainstream Managed Care, which provides comprehensive health insurance to low-income New Yorkers, has fallen even more dramatically—from 5.7 million to 4.5 million, a drop of 20.5%. The latter program remains slightly above its pre-pandemic level of 4.1 million in January 2020, but enrollment continues to drop at a rate of tens of thousands of enrollees per month. Furthermore, the Executive Budget projects virtually no enrollment increase in FY 2026: Enrollment is expected to go up by just 30,000, an increase of just 0.4 percent.

To be sure, enrollment in the state’s expensive managed long-term care programs continues to increase—it was up by nearly 41,000 members or 12 percent between December 2023 and December 2024, to a total of nearly 376,000 enrollees—but even if enrollment continues to rise at that rate, the long-term care programs will add just 45,000 new enrollees next year. One struggles to understand how such a small increase can drive a 17 percent increase in spending on the entirety of Medicaid.

Why is the governor projecting an extraordinary increase in state-share Medicaid spending—one which the Executive Budget itself describes as “unsustainable”—even as enrollment is flat or falling? To understand these projections, we must take a detour through the sometimes murky world of New York State Medicaid accounting.

What do we mean by Medicaid spending?

In New York, Medicaid is jointly funded, by local governments, the state, and the federal government. (See Figure 1.) The local share of Medicaid spending has been capped for the past decade and is currently around $8.6 billion. In FY 2025, the total state share is projected to be $37.7 billion, while the federal government will kick in $56.8 billion, for total spending of $103.1 billion. (These figures exclude funding for the Essential Plan, a separate program fully funded by the federal government.)

The vast majority of this funding goes to programs administered by the Department of Health which provide health insurance and long-term care to low-income New Yorkers. These DOH programs are what most policymakers mean when they refer to the Medicaid program without further specification, and are sometimes referred to as “DOH Medicaid.” A much smaller portion of Medicaid funding goes to other state agencies that administer healthcare programs – primarily mental health-related agencies, but also the Department of Education, foster services programs and the Department of Corrections.

Figure 1: Medicaid expenditure by source of funds and state agency, 2019-2026.

Note: Fiscal Years 2019-2024 reflect actual spending drawn from financial plan mid-year updates, while Fiscal Years 2025 and 2026 are projections drawn from the Fiscal Year 2026 Executive Budget Financial Plan. Federal share excludes Essential Plan funding. Local share funding for 2023 is estimated.

As mentioned above, “DOH (Department of Health) Medicaid” is New York’s largest Medicaid program and generates the most controversy. That’s why budgetary debate tends to focus on increases in DOH Medicaid. For example, when Governor Hochul pointed out in her budget address that Medicaid spending had grown by 14 percent, she was referring to growth in DOH Medicaid, which is projected to rise from $31.4 billion in the current fiscal year to $35.7 billion in FY 2026.

Unfortunately, it is impossible to reliably track Medicaid spending using the state’s “DOH Medicaid” figures, since the state has repeatedly and arbitrarily shifted spending between DOH Medicaid and Other State Agencies (OSA) Medicaid to avoid breaching the Medicaid Global Cap.[1] (This is why we see dramatic swings in OSA Medicaid from year to year; these swings do not reflect real changes in spending but rather accounting reclassifications.) Given the lack of figures for DOH Medicaid that are reliably comparable from year to year, in this piece we will focus on total state-share Medicaid funding.

Figure 2: Medicaid expenditure by source of funds, 2019-2026.

Note: Fiscal Years 2019-2024 reflect actual spending drawn from financial plan mid-year updates, while Fiscal Years 2025 and 2026 are projections drawn from the Fiscal Year 2026 Executive Budget Financial Plan. Federal share excludes Essential Plan funding. Local share funding for 2023 is estimated.

Medicaid Program Growth has Moderated—but Federal Support has Diminished

Combining all state-share Medicaid spending, we see a truly dramatic leap in state spending—from a projected $37.7 billion in FY 2025 to $44.1 billion in FY 2026, a 17% increase in just one year.

But this increase in state-share spending is not driven by out-of-control program growth. All-funds Medicaid spending is projected to grow far more slowly, by just 7.1%, after growing by just 1.7 percent in FY25. State-share spending is growing primarily because federal support has declined. The federal share of Medicaid, which hovered at 55 percent in the years before 2020, peaked at 60% at the height of federal pandemic relief before falling to 52% in FY 2026.

To put those figures in perspective, if the federal government’s share of Medicaid spending had stayed constant at FY 2024 levels, NYS state-share Medicaid spending would be $1.2 billion lower in FY 2025 and $4.7 billion lower in FY 2026 than is currently projected. More than half of the increase in state-share Medicaid spending is driven by decreased federal support.

Figure 3: Medicaid expenditure by source of funds, 2019-2026.

Note: FPI calculation based on DOB data.

The reduction in federal Medicaid funding (from extremely high levels in FY 2021-22) is a fiscal reality the state must address. But this reduction does not reflect long-term trends in Medicaid enrollment or utilization.

What explains the decrease in federal-share spending in FY 2026? While the Executive Budget Financial Plan does not provide much detail on this issue, two causes seem to be at work. In FY 2025, the state received the final tranche of enhanced federal matching funds from the American Rescue Plan, a total of $764 million in federal funds which will be replaced by state dollars in FY 2026. In addition, the Executive Budget appears to assume that New York’s allotment of federal Disproportionate Share Hospital funding will be reduced, pursuant to a long-deferred provision of the Affordable Care Act, which will result in a reduction of $1.4 billion in federal spending.[2]

Accounting for the MCO Tax

A major feature of the FY 2026 state budget is implementation of the MCO tax, a new provider tax levied on Medicaid and Essential Plan MCOs. I discussed the MCO tax in a policy brief last year, but will briefly review it here.

The MCO tax is a way of drawing down increased federal Medicaid funding. Schematically, the way it will work is that the state will tax Medicaid and Essential Plan MCOs and then spend the resulting revenue, plus an additional federal match. So, for example, the state could levy a $100 tax on Medicaid MCOs and pay the MCOs back $50 in state Medicaid funds plus a $50 federal match. The MCOs would then be made whole, but the state would retain $50, which it could spend on other Medicaid program areas, receiving an additional federal match. In the aggregate, the state would be taking $100 from the MCOs, paying them back $100, and receiving a $100 federal match – effectively generating $100 in additional federal Medicaid spending at no cost to the state.

The state recently won federal approval for an MCO tax structured like this, and the Executive Budget provides details on how it will work. The state will receive $3.3 billion in taxes from Medicaid, CHP and Essential Plan MCOs. It will pay the Medicaid MCOs back for their share of the tax, using $1.2 billion in state funds and approximately $2.6 billion in federal funds.[3] This leaves the state with $2.1 billion in state dollars, of which it will spend $1.4 billion on FY 2026 Medicaid and reserve $646 million for future years. (See Table 1.)

Table 1. MCO Tax Spending (Millions)

Note: FPI calculation based on DOB data.

How does this financial maneuver impact Medicaid spending? The Executive Budget accounts for it as a $2.6 billion net increase in state-share Medicaid spending in FY 2026 — $1.2 billion in MCO reimbursement and $1.4 billion in other spending. This new $2.6 billion represents a large share of the overall $4.3 billion increase in state-share DOH Medicaid spending.

I would argue that this is quite misleading. Certainly, the $1.4 billion in program spending represents real growth in Medicaid costs (largely due to provider rate increases). But the $1.2 billion the state spends to reimburse MCOs does not reflect growth in Medicaid; no extra services are provided, no new enrollees are served, and no providers are paid more due to this spending. It is simply one side of a wash transaction: The MCOs pay the state, and the state pays the MCOs. The two payments simply cancel out.

It may be easiest to recognize this by considering a common criticism of the MCO tax. Many skeptics are concerned that the federal government may someday withdraw approval for the MCO tax, creating a “fiscal cliff” as the state is forced to make up lost MCO tax revenue. That is a reasonable fear when it comes to the $1.4 billion in program spending – if the MCO tax no longer pays for it, then the state will have to find another source of revenue or cut rates. But it is most certainly not true for the $1.2 billion in MCO tax reimbursement. If the federal government withdraws approval for the tax structure, then the state will stop collecting the tax and stop reimbursing the MCOs for the tax, leaving the MCOs no worse off than they are now.

In short, the $1.2 billion state share and $2.6 billion all-funds increase in Medicaid spending due solely to MCO reimbursement is illusory. Whatever one may think of the MCO tax as a whole, this aspect of it does not reflect real program growth.[4]

Classifying this spending appropriately brings state-share Medicaid spending down by $1.2 billion and all-funds Medicaid spending growth down by $2.6 billion. With this adjustment, all-funds Medicaid spending in FY 2026 is not $110.6 billion but $108 billion – and all-funds spending growth is not 7.2 percent but 4.7 percent.

The DPT Recoupment Saga

Finally, the Executive Budget’s account of Medicaid growth is affected by a one-time blip in Medicaid spending: The “Directed Payment Template recoupment,” the repayment of a large loan the State made to financially distressed hospitals in the period from FY 2022 to FY 2024.

Here’s the background: The Directed Payment Template is a Medicaid program to provide support for safety-net hospitals. The program was set to begin in FY 2022, but delays in federal approval meant that federal funding wasn’t available in time. To avoid burdening safety-net hospitals, the State loaned them the money, with the expectation that hospitals would pay the state back once they received federal funds. However, for unclear reasons not all of this money has been paid back.

The state accounted for this loan by recording an extra $915 million in Medicaid spending in fiscal year 2024 (reflecting the cost of the loan) and an offsetting negative-$915 million payment in fiscal year 2025 (reflecting the expectation that the loan would be repaid). This has the effect of artificially lowering fiscal year 2025 Medicaid spending: In fact, state-share program spending was $38.6 billion, but the state reported it at $37.7 billion to reflect the repayment of the loan.

It is not clear why the repayment has been delayed, or when repayment might occur. But the effect of accounting for it as negative spending in FY 2025 is to exaggerate spending growth in FY 2026.

Summary

Putting all this together gives a very different picture of Medicaid spending growth than was presented in the executive budget: All-funds Medicaid spending on core programs is growing by just 3.7%. This compares favorably with private-sector projections that healthcare spending may increase by as much as 8% in 2025.[5]

Table 2: Adjusted All-Funds Medicaid Spending (Millions)

Conclusion: In Evaluating Medicaid Costs, Focus on the Program

Medicaid is a complex program – it is jointly funded by the state and federal governments, its spending is shaped by enrollment, utilization and provider rates, and in recent years it has been subject to rapid changes in both federal policy and economic conditions. All these variables can distort our view of total program spending. For this reason, it is important to separate shifts in the source of funds for Medicaid spending from shifts in the actual spending, and to separate one-time accounting changes from long-term trends in enrollment, utilization and provider rates.

Failure to distinguish these issues can seriously distort our understanding of how the Medicaid program is evolving. For example, much recent coverage of the Medicaid budget has argued that the program is experiencing spiraling spending growth driven by high long-term care spending and utilization. In fact, as we have seen, Medicaid spending growth is projected to be quite modest this year, and reported dramatic increases in spending are driven largely by accounting issues and decreased federal funding.

To be sure, state-share spending is important, even if it reflects reduced federal support rather than real program growth. Even adjusting for MCO reimbursement and one-time hospital payments, state-share all-agency Medicaid spending is expected to grow by $4.3 billion in FY 2026 due to decreased federal support. If federal policy remains stable then this is likely to be a one-time increase, but if the Trump administration cuts Medicaid at the federal level, then state policymakers will need to consider spending cuts or new sources of revenue, even if program growth remains modest.

Even so, understanding why state Medicaid costs are rising will be critical. If New York’s Medicaid program really were growing at an annualized rate of 17.1 percent at a time of flat enrollment, then the program would urgently require dramatic reform, regardless of federal policy. But as we have seen, spending is rising at a rate of less than 4 percent – far from unreasonable for a program that provides the sole source of long-term care coverage in a state with an aging population. Medicaid spending is growing, but it is not out of control or unsustainable, and policymakers should approach calls for cuts with caution.

Sources

[1] The state is legally required to keep DOH Medicaid spending beneath a set level (the DOH Global Cap). In recent years it has managed this by repeatedly reclassifying DOH Medicaid spending as Mental Hygiene spending, primarily through an accounting mechanism known as the Mental Hygiene Stabilization Fund. In the FY 2026 Executive Budget the state announced a permanent reclassification of $2.3 billion in spending from the Health line to the Mental Hygiene line.

[2] Even accounting for these figures, a 52 percent effective FMAP seems remarkably low. New York’s overall FMAP is 50%, but it receives higher match rates for special populations and services, such as the ACE New Adult Group (90% FMAP) and Community First Choice Option services (56% FMAP). These categories would be expected to raise the overall FMAP above 52 percent. Why, then, is the real figure so low? I suspect that the figure reflects substantial categories of state funding which receive no federal match at all, such as for Medicaid coverage of some categories of undocumented immigrants and unmatched aid to financially distressed providers.

[3] I estimate an effective FMAP on MCO Tax spending of 53.1 percent, using the FY 2026 Executive Budget figures for MCO tax-related state-share spending ($2.632 billion) and all-funds impact ($2.977 billion).

[4] Readers may wonder why the MCO tax has any impact at all on state-share spending – if the whole exercise is just a maneuver to generate more federal reimbursement, shouldn’t it simply increase the federal share of Medicaid, leaving state-share spending unchanged? But this is not quite the right way to think about it. The $3.278 billion in taxes paid by the MCOs is state tax revenue, no different from sales tax.

[5] https://www.pwc.com/us/en/industries/health-industries/library/behind-the-numbers.html