Understanding Childcare Policy in New York

November 1, 2024 |

Recent reforms and challenges

Childcare’s unaffordability in New York is an acute burden for families across the state and across the income distribution. New York’s childcare industry faces dual challenges: despite prices that are prohibitively high for many families, childcare providers struggle to remain in business and tend to furnish their workers with inadequate wages. To redress these issues, the State has made recent investments in the childcare sector, expanding its childcare subsidies and providing a series of one-off wage supplements to childcare workers.

Nevertheless, childcare affordability will remain a significant challenge in the years ahead. While some further improvements have yet to be enacted, recent expansions to the State’s childcare subsidies have pushed the program near its maximum generosity under federal rules. With high cost burdens for middle-income families who are ineligible for the subsidy program, some advocates and lawmakers have begun arguing for a universal approach to childcare.

This brief will first discuss New York’s childcare challenges before describing the current policies the State uses to support childcare providers and low- and moderate-income families seeking childcare. The brief then provides an overview of remaining challenges facing the childcare sector and proposals to expand State support for it.

New York’s childcare challenges

Childcare in New York State is unaffordable for many families, yet inadequately supports its workers. The State’s childcare costs are the third highest in the U.S., putting a strain on family budgets across the income distribution.[1] The cost crisis is especially severe in New York City. Two boroughs, the Bronx and Brooklyn, have the costliest childcare as a share of family income of any county in the U.S. (Queens is the fourth highest).[2] This cost crisis plays a central role in the city and state’s broader affordability crisis: families with young children are 40 percent more likely to leave New York State than those without young children. Those living in New York City are more than twice as likely to leave the city as those without young children.[3]

While childcare affordability creates strains for New York families, the industry’s high costs are inadequate to provide decent wages for its workers. Childcare is a labor-intensive industry, with State law specifying staffing ratios (for instance, one supervisor is required for every four infants).[4] These high costs result in low wages for childcare workers. The median childcare worker in New York State earns $32,900 – 39 percent lower than the statewide median wage.[5]

Despite the low wages paid to workers, many smaller childcare providers have struggled to remain in business in recent years. Since the beginning of the Covid pandemic, the number of childcare seats offered by family daycares, which operate out of residences, fell by 5 percent. This lost capacity was compensated for by an increase in the number of seats provided by daycare centers. Daycare centers care for more children than family providers. While this allows for greater operational efficiency, they are more expensive than family daycares. An increase in daycare centers since Covid pushed a statewide childcare capacity to 796,000 seats in 2023, a gain of 5,000 seats, or 0.6 percent.[6][7]

Subsidizing Childcare: An overview of the Child Care Assistance Program

In response to the growing crisis of childcare affordability, State lawmakers have taken steps to support low- and middle-income families and childcare providers, subsidizing access to childcare and, in recent years, temporarily supporting the incomes of childcare workers.

17 percent of families with young children receive childcare assistance from the State

The State’s primary policy tool to support families’ access to childcare is the Child Care Assistance Program (CCAP). CCAP provides vouchers that pay for childcare for families with income below 85 percent of New York State’s median income. For a family of three, this threshold is $91,251. CCAP vouchers can pay for a broad range of childcare services for children under the age of 13, including after-school programs for children enrolled in primary school.

CCAP vouchers can also be for used for “legally exempt” providers: non-licensed and informal childcare providers. These providers can include relatives – not including parents and those who live in a separate residence – and friends. These providers are exempt from standard licensing requirements but must still meet basic safety requirements, including background checks. Reimbursement rates for these providers are lower than other providers, as discussed in the next section.

Of New York’s approximate 460,000 households with children under the age of six, just under half, about 210,000 households, are eligible for CCAP.[8] Of these, 80,000 families (comprising 147,000 children) received CCAP benefits in federal fiscal year 2023.[9] While many income-eligible families may decide to forgo childcare of any type altogether, others face barriers to participation. These barriers include finding a provider, especially if care is needed for non-traditional hours, work requirements and administrative hurdles, and immigration status.

How the value of CCAP vouchers is set

CCAP vouchers pay for childcare up to a price level determined by the State’s Office of Children and Family Services (OCFS). OCFS establishes the price of childcare by surveying a sample of childcare providers every two to three years and setting the CCAP voucher level at the cost of 80th percentile of providers. That is, the CCAP voucher level is meant to exceed the price set by 80 percent of providers, with the remaining 20 percent of providers using higher prices. Different CCAP voucher rates are set for each provider type (for instance, daycare centers versus family daycares), age of child, and region of the state. CCAP’s highest voucher rates are for infant care provided by daycare centers in New York City, which were set at $500 per week in 2024, the most recent market survey. Lower rates are set for residential-based daycares, older children, and less costly regions of the state. For instance, vouchers for infants in family daycares in rural counties will pay up to $279 per week for infant care.[10]

If a childcare provider selected by a CCAP recipient charges less than the CCAP market rate, the voucher will pay providers that lower price. Conversely, families can use vouchers on providers who charge above the maximum voucher level and pay the difference out of pocket.

Families receiving CCAP vouchers are required to pay part of the cost of their childcare. OCFS requires that families’ cost share equal one percent of the income they earn above the federal poverty measure. In 2024, the federal poverty measure for a family of three was $25,820. A family of three earning $50,000 would have to contribute about $5 per week to receive voucher benefits. As such, families’ net CCAP benefit is the value of the voucher payment to their childcare provider minus their family share.

CCAP carries work requirements for participating families. For families enrolled in other public assistance programs, work requirements are set by the local social service district (LSSDs), the county-level agencies that administer CCAP. In New York City, for instance, those working at least 10 hours per week are eligible for CCAP.[11] Those looking for work, living with disabilities, or engaged in job training or education programs are also eligible for CCAP.[12]

Funding, administering, and expanding CCAP: Coordination between federal, state, and local government

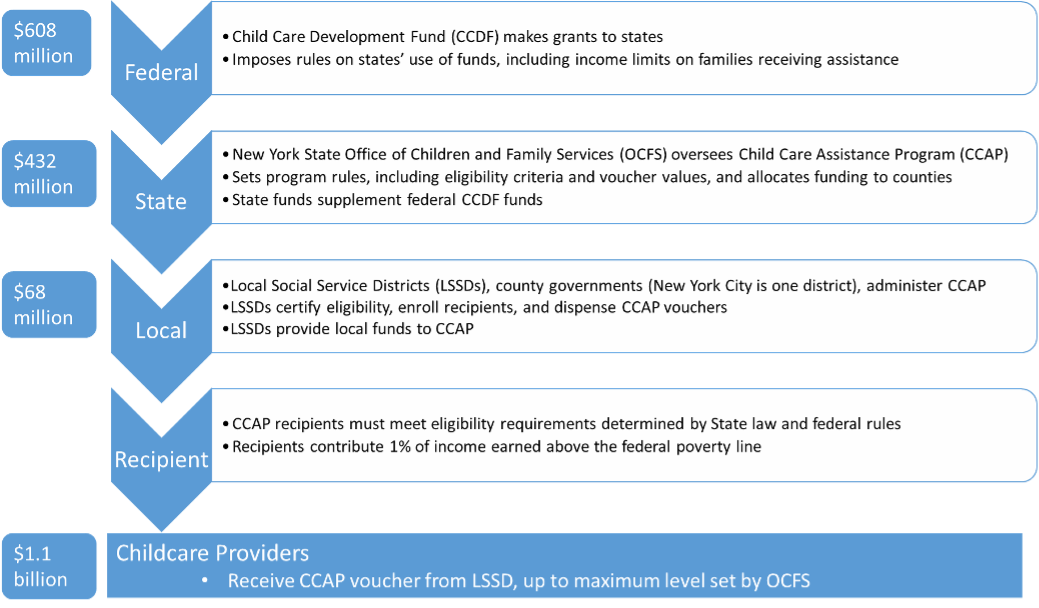

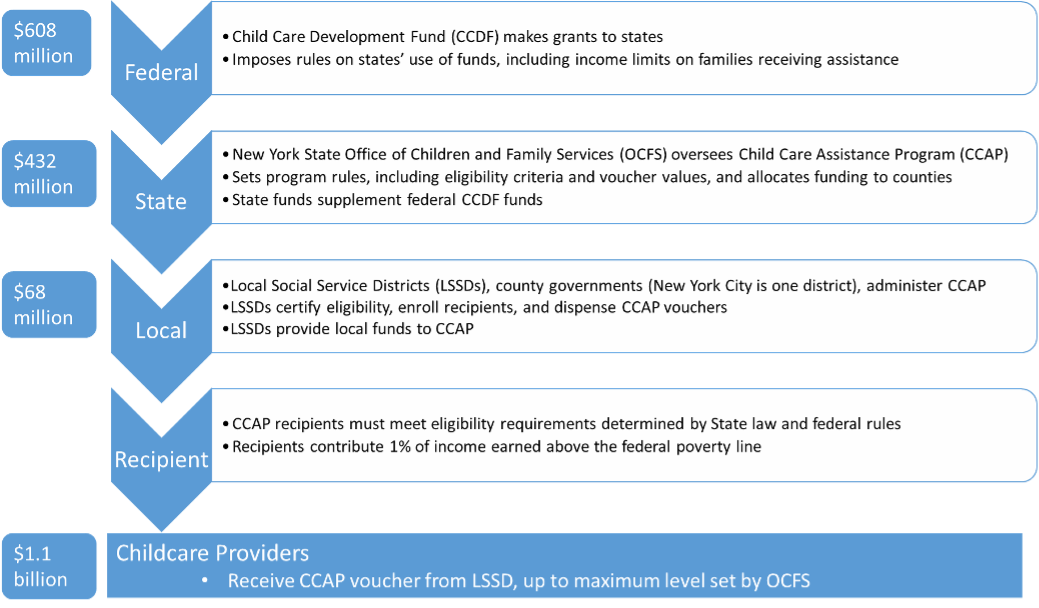

New York’s CCAP is part of the federal Child Care Development Fund (CCDF) program. New York’s program is regulated by the federal and State governments, administered by local governments across the State, and funded jointly by the federal, State, and local governments.

The federal CCDF allocates funds to states, which supplement those grants with state funding before suballocating to localities. In fiscal year 2024, the federal government’s Child Care Development Block Grant (CCDBG) allocated $11.3 billion to state CCDF programs. New York’s share of this funding was $607.9 million.[13] Further, the State shifts a portion of its federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) grant to its childcare program. For fiscal year 2025, the State shifted $464 million of these funds.[14]

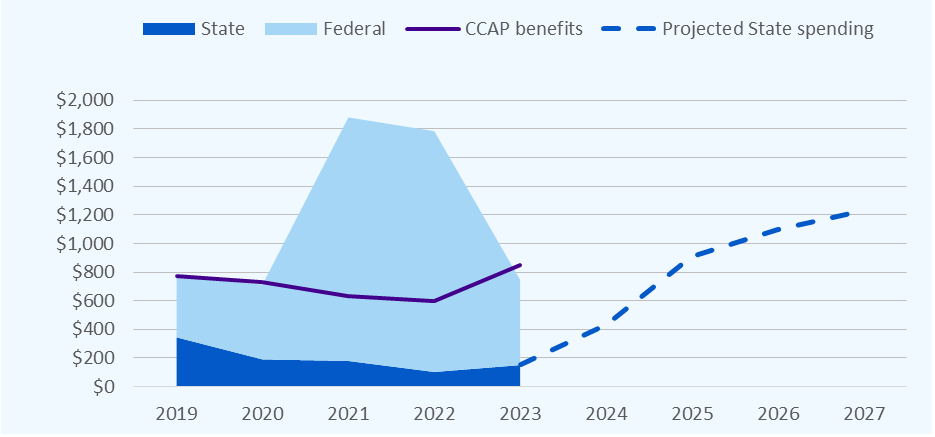

The expansions to CCAP that the State has enacted in recent years (discussed below) were accompanied by a sharp increase in the program’s State and federal funding. New York’s federal CCDF allocations rose sharply during the Covid pandemic, as federal relief bills, most notably the American Rescue Plan Act, made heavy, though temporary, investments in childcare. As a result, federal funding rose from a pre-Covid baseline of $425 million to a peak of $2.8 billion in federal fiscal year 2021 (which spans State fiscal years 2021 and 2022).

The extraordinary, temporary influx of federal aid during Covid resulted in allocations to LSSDs far exceeding actual CCAP benefits. This led to surplus funds held by LSSDs, which can rollover into future years. CCAP costs will rise in the near-term as recent reforms push up both enrollment and voucher values. Further, some of this funding was used for other childcare programs, including worker wage supplements (discussed below).

As a temporary influx of federal Covid relief funding recedes, State funding is set to rise briskly. In fiscal year 2020, the State spent $191 million on childcare.[15] In fiscal year 2025, the State expects to spend $908 million, bringing total State and federal funding to $2 billion. State spending will rise to $1.2 billion in future years as the State assumes the costs of services funded with temporary federal funding appropriated during the Covid pandemic.[16]

Figure 1. CCAP funding, spending, and projected State funding, State fiscal years 2019 to 2027

Millions of dollars

Note: CCAP benefits equal combined federal and state funding. Projection is only for state funding because federal and state budget documents do not make projections of anticipated federal allocations.

Finally, local governments, which administer CCAP, also fund a share of its costs. OCFS apportions State and federal CCAP funds to counties (which the State refers to as LSSDs) based on historical program usage for each district. In turn, LSSDs must contribute a local share. The local share has been frozen since federal fiscal year 1997, and was calculated as equal to 25 percent of the costs of cases for families receiving public assistance. In fiscal year 2024 this local share totaled $68 million. New York City accounted for $53 million (78 percent) of the statewide local contribution. This local contribution was additive to $945 million in combined federal and state allocations in fiscal year 2024.

Once this local share is met, LSSDs can disburse funds up to their maximum State allocation. Any unused State funds can be rolled over into future years. At the end of federal fiscal year 2023, all LSSDs had a balance of unused funds, reflecting an ability to serve all qualifying families.[17]

CCAP is funded and implemented by multiple levels of government

Dollars are for fiscal year 2024

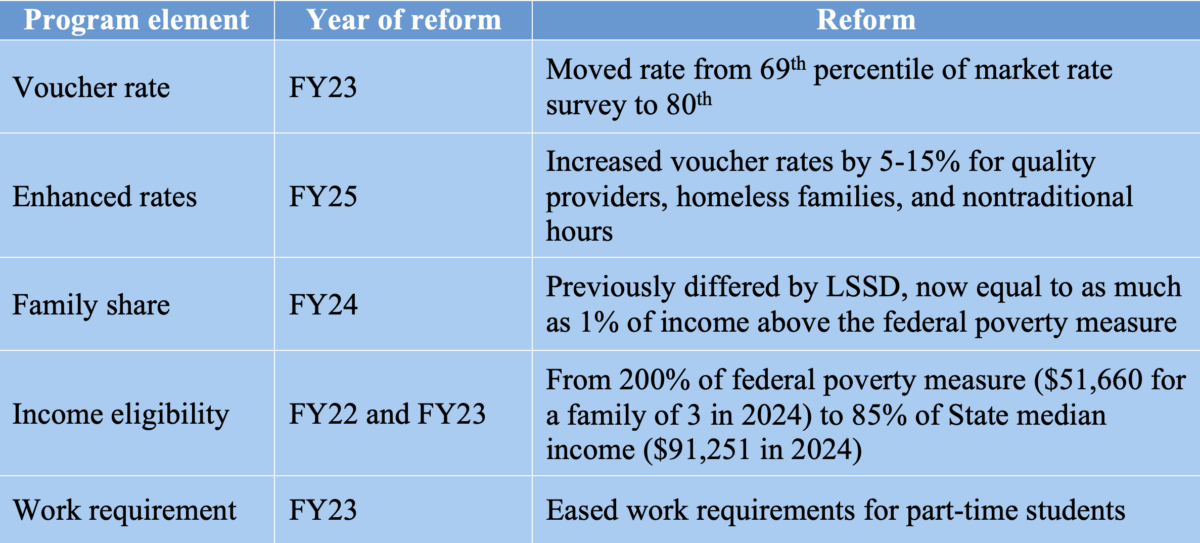

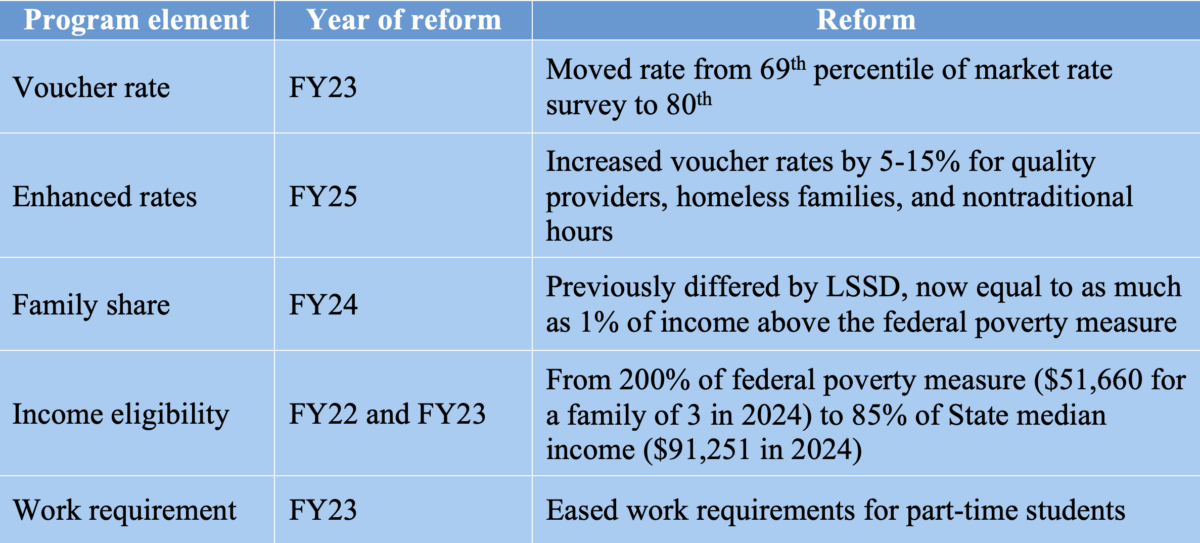

Recent CCAP reforms have increased eligibility and uptake

In recent years, New York has ramped up investment in CCAP, expanding the program to be nearly as expansive as possible under the federal rules. In fiscal year 2024, the State expanded CCAP eligibility to 85 percent of the state median income – the maximum allowable income under federal rules. The prior year, the State moved eligibility from 200 percent of the federal poverty measure to 300 percent – a level about 10 percent lower than the new, median income-based threshold. Together, these changes increased eligibility from just over one-quarter (27.2 percent) of New York households with children under the age of 6 to nearly half (45.5 percent).[18]

Further, in fiscal year 2023, the State increased the value of CCAP vouchers from the 69th percentile of market prices to the 80th percentile. Recent changes have also assigned higher voucher rates for childcare providers that meet established quality requirements above the requisite licensing requirements. Vouchers supporting homeless children and families and families working non-traditional hours also receive enhanced rates. Rate enhancements can increase voucher levels by 5 to 15 percent, at the discretion of LSSDs.

Finally, in recent years, the State has lowered the hours required to meet CCAP work requirements from 20 hours per week to 10 hours, expanded the educational programs exempt from work requirements, and reduced families’ required copayments, which had previously varied by LSSD, to 1 percent of income earned above the poverty measure.[19]

These expansions have increased families’ uptake of CCAP. The Covid pandemic was a severe setback for the childcare industry, forcing many providers to temporarily shutter and disrupting many families’ economic situations, affecting their demand for childcare. As a result, CCAP participation fell from 101,000 families in federal fiscal year 2019 to just 60,000 in federal fiscal year 2021. Program use remained depressed for the following year before surging to 80,000 in federal fiscal year 2023, the most recent year for which data is available.[20] Monthly use reports indicate that CCAP uptake has continued to accelerate, surpassing pre-Covid levels by early 2024.[21]

Recent reforms to CCAP

What’s next for CCAP

The State’s expansions to CCAP have incrementally expanded support for low- and middle-income families, reaching the maximum income eligibility threshold allowed under federal rules. Still, advocates point to additional steps that would facilitate greater access to childcare subsidies among currently-eligible families and expand eligibility to additional families.

First, lawmakers and advocates argue that delays in processing CCAP applications create a hardship for low-income workers. The establishment of presumptive eligibility, which would direct LSSDs to provide benefits to applicants while verifying eligibility, would overcome this challenge.[22]

Second, advocates argue that barriers remain for undocumented immigrants and for families who work non-traditional or irregular hours. CCAP requires that the hours of care match parents’ work hours, posing a challenge for those with jobs with fluctuating hours.[23] Proposed legislation would decouple care hours from hours worked.[24] Further legislation would remove CCAP’s requirement that applicants earn at least the minimum wage, a requirement that may bar families working irregular jobs.[25]

Finally, advocates challenge the validity of the market survey used to set CCAP voucher rates. Advocates argue that the market survey captures the prices of a market that depends on paying its workers inadequate wages. An alternative method for setting voucher prices would estimate the costs of providing childcare, calculating the prices of inputs, including rent and wages, for each region. The cost modeling approach is allowed under federal rules, and currently used by New Mexico and DC.[26]

Supplementing childcare worker wages

The inadequate wages paid to childcare workers is a longstanding challenge. Low wages hurt workers and make it difficult for childcare providers to attract and retain staff. In fiscal year 2024, the State took the unprecedented step of making wage supplement payments to childcare workers. The State appropriated $500 million in federal Covid relief funding for one-time payments of up to $3,000 per worker to childcare workers.[27] At the end of the year, having disbursed awards to all qualified applicants, $150 million of these funds were left over. In fiscal year 2025, the State appropriated $280 million in unused federal funds for a second round of payments. Importantly, these payments are temporary and funded with temporary resources, rather than a recurring State-funded commitment. Further, providers must apply for these payments, and low awareness may hinder program reach. Advocates have called for a permanent $1.2 billion fund to provide each childcare worker with a $12,500 annual wage supplement.[28]

Other State-led childcare initiatives

The State also launched two small-scale programs to support childcare in fiscal year 2024: 1) a pilot to sponsor employer-provided childcare and 2) a tax credit for childcare expansions. The $5 million employer-supported childcare pilot would sponsor childcare centers that split costs between the State, employers, and parents, making services available to those earning between 85 and 100 percent of the state median income – just above CCAP eligibility. The State has been slow to roll out this initiative.[29] Second, the State established the $50 million Child Care Creation and Expansion Tax Credit, which offsets the business tax liability of childcare providers that create new capacity in 2023 or 2024.

The future of New York’s childcare

Despite recent progress, the unaffordability of childcare remains a significant challenge for New York families. Only a small share of New Yorkers were affected by recent changes, and recent changes have had no effect on families above the CCAP eligibility threshold. Still, childcare costs continue to weigh on many working and middle-income families. For this reason, policymakers have begun exploring alternative models for childcare that go beyond the existing CCAP subsidies and establish universal access to affordable childcare in New York.

While barriers to CCAP benefits remain, the program is approaching its maximum reach allowed under federal regulations. This limits the State’s ability to support moderate-income families in need of childcare. In particular, the federally-imposed income limit of 85 percent of State median income creates a sharp benefits cliff. A middle-income family earning just above this limit ($91,251 for a family of three) would entirely lose access to CCAP benefits, a loss of as much as $21,000. Expansions to childcare support for middle-income families, therefore, would require entirely State-funded programs working in parallel with the federally-backed CCAP.

In 2018, Governor Cuomo established a task force composed of public officials, advocates and researchers, labor, childcare providers, and other stakeholders to study the availability and accessibility of childcare throughout the state and make recommendations for addressing any shortcomings. The task force was extended in 2021 and released its second annual final report in April 2024.[30] The 2024 report included recommendations to permanently supplement workers’ wages and provide workforce development support; continue to expand CCAP, including by adopting cost modeling; and increase the supply of quality childcare providers. Finally, the task force is set to release a report by the end of 2024 outlining a roadmap to statewide universal childcare.

While the task force avoided making concrete recommendations for universal childcare, instead putting forward guidelines for planning such a policy, it did recommend creating a pilot program to test the feasibility of universal childcare, gather data on program use, and provide insight on policy design. This recommendation is advanced by a bill recently introduced in the New York State Senate that would establish twenty pilot locations for childcare centers offering universal admissions fully funded by the State.[31]

This work continues policy advocacy launched in 2022 when two bills proposed establishing statewide universal childcare.[32] While neither bill was adopted, advocates have increasingly pushed to continue incremental expansions in the State’s support for childcare with the goal of building a system of universal affordable coverage.[33]

[1] https://www.dol.gov/agencies/wb/topics/featured-childcare

[2] https://www.dol.gov/agencies/wb/topics/childcare/price-by-age-care-setting

[3] https://fiscalpolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/FPI-Migration-Pt-2.pdf

[4] https://ocfs.ny.gov/programs/childcare/regulations/418-1-DCC.pdf

[5] https://ecommons.cornell.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/71c61a1c-d893-4804-abff-41e618634bd2/content

[6] https://ocfs.ny.gov/programs/childcare/assets/docs/factsheets/2023-DCCS-Fact-Sheet.pdf; https://ocfs.ny.gov/programs/childcare/assets/docs/factsheets/2019-DCCS-Fact-Sheet.pdf

[8] https://fiscalpolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/FPI-FY-2024-Budget-Briefing-Book.pdf

[9] https://ocfs.ny.gov/programs/childcare/assets/docs/factsheets/2023-DCCS-Fact-Sheet.pdf. CCAP enrollment includes eligible children under the age of 13. Nevertheless, the large majority of CCAP is for children under six, who have not yet enrolled in kindergarten.

[10] https://ocfs.ny.gov/main/policies/external/2024/lcm/24-OCFS-LCM-22.pdf

[11] https://www.nyc.gov/site/acs/early-care/apply-child-care.page

[12] https://ocfs.ny.gov/programs/childcare/regulations/415-Child-Care-Services.pdf

[13] https://www.acf.hhs.gov/occ/data/gy-2024-ccdf-allocations-based-appropriations

[14] https://scaany.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Schuyler-Center-Last-Look-2024-25-Enacted-Budget-04302024.pdf

[15] https://www.budget.ny.gov/pubs/archive/fy21/enac/fy21-enacted-fp.pdf; This value is primarily comprised of CCAP, although other smaller childcare initiatives are included.

[16] https://www.budget.ny.gov/pubs/archive/fy25/en/fy25fp-en.pdf

[17] https://ocfs.ny.gov/main/policies/external/2023/lcm/23-OCFS-LCM-12-R3.pdf

[18] https://fiscalpolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/FPI-FY-2024-Budget-Briefing-Book.pdf

[19] https://ocfs.ny.gov/main/policies/external/ocfs_2021/ADM/21-OCFS-ADM-30.pdf

[20] https://ocfs.ny.gov/programs/childcare/data/

[21] https://ocfs.ny.gov/programs/childcare/assets/docs/ccap/NYCCAP-Family-Child-Counts-2024May.pdf

[22] (A.4099 (Clark)/ S.4667 (Brouk)

[23] https://empirestatechildcare.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Removing-Barriers-1-Pager.pdf

[24] https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/bills/2023/S5327/amendment/A

[25] (A.1303 (Clark)/S.4924(Ramos)

[26] https://www.americanprogress.org/article/states-can-improve-child-care-assistance-programs-through-cost-modeling/

[27] Grants are only available to childcare workers in caring roles who work at least 15 hours per week. https://ocfs.ny.gov/programs/childcare/grants/workforce-grant/

[28] https://empirestatechildcare.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/NEW-Updated-2024-Post-Budget-Priorities.pdf

[29] https://capitolpressroom.org/2024/04/23/hochul-administration-slow-to-realize-touted-child-care-initiatives/

[30] https://ocfs.ny.gov/programs/childcare/availability/CCATF-Relaunch-Legislation.pdf

[31] https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/bills/2023/S9853

[32] https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/bills/2023/S3245; https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/bills/2021/s7615

[33] https://empirestatechildcare.org/what-is-universal-child-care/victories-on-the-path-to-universal-child-care/

Understanding Childcare Policy in New York

November 1, 2024 |

Recent reforms and challenges

Childcare’s unaffordability in New York is an acute burden for families across the state and across the income distribution. New York’s childcare industry faces dual challenges: despite prices that are prohibitively high for many families, childcare providers struggle to remain in business and tend to furnish their workers with inadequate wages. To redress these issues, the State has made recent investments in the childcare sector, expanding its childcare subsidies and providing a series of one-off wage supplements to childcare workers.

Nevertheless, childcare affordability will remain a significant challenge in the years ahead. While some further improvements have yet to be enacted, recent expansions to the State’s childcare subsidies have pushed the program near its maximum generosity under federal rules. With high cost burdens for middle-income families who are ineligible for the subsidy program, some advocates and lawmakers have begun arguing for a universal approach to childcare.

This brief will first discuss New York’s childcare challenges before describing the current policies the State uses to support childcare providers and low- and moderate-income families seeking childcare. The brief then provides an overview of remaining challenges facing the childcare sector and proposals to expand State support for it.

New York’s childcare challenges

Childcare in New York State is unaffordable for many families, yet inadequately supports its workers. The State’s childcare costs are the third highest in the U.S., putting a strain on family budgets across the income distribution.[1] The cost crisis is especially severe in New York City. Two boroughs, the Bronx and Brooklyn, have the costliest childcare as a share of family income of any county in the U.S. (Queens is the fourth highest).[2] This cost crisis plays a central role in the city and state’s broader affordability crisis: families with young children are 40 percent more likely to leave New York State than those without young children. Those living in New York City are more than twice as likely to leave the city as those without young children.[3]

While childcare affordability creates strains for New York families, the industry’s high costs are inadequate to provide decent wages for its workers. Childcare is a labor-intensive industry, with State law specifying staffing ratios (for instance, one supervisor is required for every four infants).[4] These high costs result in low wages for childcare workers. The median childcare worker in New York State earns $32,900 – 39 percent lower than the statewide median wage.[5]

Despite the low wages paid to workers, many smaller childcare providers have struggled to remain in business in recent years. Since the beginning of the Covid pandemic, the number of childcare seats offered by family daycares, which operate out of residences, fell by 5 percent. This lost capacity was compensated for by an increase in the number of seats provided by daycare centers. Daycare centers care for more children than family providers. While this allows for greater operational efficiency, they are more expensive than family daycares. An increase in daycare centers since Covid pushed a statewide childcare capacity to 796,000 seats in 2023, a gain of 5,000 seats, or 0.6 percent.[6][7]

Subsidizing Childcare: An overview of the Child Care Assistance Program

In response to the growing crisis of childcare affordability, State lawmakers have taken steps to support low- and middle-income families and childcare providers, subsidizing access to childcare and, in recent years, temporarily supporting the incomes of childcare workers.

17 percent of families with young children receive childcare assistance from the State

The State’s primary policy tool to support families’ access to childcare is the Child Care Assistance Program (CCAP). CCAP provides vouchers that pay for childcare for families with income below 85 percent of New York State’s median income. For a family of three, this threshold is $91,251. CCAP vouchers can pay for a broad range of childcare services for children under the age of 13, including after-school programs for children enrolled in primary school.

CCAP vouchers can also be for used for “legally exempt” providers: non-licensed and informal childcare providers. These providers can include relatives – not including parents and those who live in a separate residence – and friends. These providers are exempt from standard licensing requirements but must still meet basic safety requirements, including background checks. Reimbursement rates for these providers are lower than other providers, as discussed in the next section.

Of New York’s approximate 460,000 households with children under the age of six, just under half, about 210,000 households, are eligible for CCAP.[8] Of these, 80,000 families (comprising 147,000 children) received CCAP benefits in federal fiscal year 2023.[9] While many income-eligible families may decide to forgo childcare of any type altogether, others face barriers to participation. These barriers include finding a provider, especially if care is needed for non-traditional hours, work requirements and administrative hurdles, and immigration status.

How the value of CCAP vouchers is set

CCAP vouchers pay for childcare up to a price level determined by the State’s Office of Children and Family Services (OCFS). OCFS establishes the price of childcare by surveying a sample of childcare providers every two to three years and setting the CCAP voucher level at the cost of 80th percentile of providers. That is, the CCAP voucher level is meant to exceed the price set by 80 percent of providers, with the remaining 20 percent of providers using higher prices. Different CCAP voucher rates are set for each provider type (for instance, daycare centers versus family daycares), age of child, and region of the state. CCAP’s highest voucher rates are for infant care provided by daycare centers in New York City, which were set at $500 per week in 2024, the most recent market survey. Lower rates are set for residential-based daycares, older children, and less costly regions of the state. For instance, vouchers for infants in family daycares in rural counties will pay up to $279 per week for infant care.[10]

If a childcare provider selected by a CCAP recipient charges less than the CCAP market rate, the voucher will pay providers that lower price. Conversely, families can use vouchers on providers who charge above the maximum voucher level and pay the difference out of pocket.

Families receiving CCAP vouchers are required to pay part of the cost of their childcare. OCFS requires that families’ cost share equal one percent of the income they earn above the federal poverty measure. In 2024, the federal poverty measure for a family of three was $25,820. A family of three earning $50,000 would have to contribute about $5 per week to receive voucher benefits. As such, families’ net CCAP benefit is the value of the voucher payment to their childcare provider minus their family share.

CCAP carries work requirements for participating families. For families enrolled in other public assistance programs, work requirements are set by the local social service district (LSSDs), the county-level agencies that administer CCAP. In New York City, for instance, those working at least 10 hours per week are eligible for CCAP.[11] Those looking for work, living with disabilities, or engaged in job training or education programs are also eligible for CCAP.[12]

Funding, administering, and expanding CCAP: Coordination between federal, state, and local government

New York’s CCAP is part of the federal Child Care Development Fund (CCDF) program. New York’s program is regulated by the federal and State governments, administered by local governments across the State, and funded jointly by the federal, State, and local governments.

The federal CCDF allocates funds to states, which supplement those grants with state funding before suballocating to localities. In fiscal year 2024, the federal government’s Child Care Development Block Grant (CCDBG) allocated $11.3 billion to state CCDF programs. New York’s share of this funding was $607.9 million.[13] Further, the State shifts a portion of its federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) grant to its childcare program. For fiscal year 2025, the State shifted $464 million of these funds.[14]

The expansions to CCAP that the State has enacted in recent years (discussed below) were accompanied by a sharp increase in the program’s State and federal funding. New York’s federal CCDF allocations rose sharply during the Covid pandemic, as federal relief bills, most notably the American Rescue Plan Act, made heavy, though temporary, investments in childcare. As a result, federal funding rose from a pre-Covid baseline of $425 million to a peak of $2.8 billion in federal fiscal year 2021 (which spans State fiscal years 2021 and 2022).

The extraordinary, temporary influx of federal aid during Covid resulted in allocations to LSSDs far exceeding actual CCAP benefits. This led to surplus funds held by LSSDs, which can rollover into future years. CCAP costs will rise in the near-term as recent reforms push up both enrollment and voucher values. Further, some of this funding was used for other childcare programs, including worker wage supplements (discussed below).

As a temporary influx of federal Covid relief funding recedes, State funding is set to rise briskly. In fiscal year 2020, the State spent $191 million on childcare.[15] In fiscal year 2025, the State expects to spend $908 million, bringing total State and federal funding to $2 billion. State spending will rise to $1.2 billion in future years as the State assumes the costs of services funded with temporary federal funding appropriated during the Covid pandemic.[16]

Figure 1. CCAP funding, spending, and projected State funding, State fiscal years 2019 to 2027

Millions of dollars

Note: CCAP benefits equal combined federal and state funding. Projection is only for state funding because federal and state budget documents do not make projections of anticipated federal allocations.

Finally, local governments, which administer CCAP, also fund a share of its costs. OCFS apportions State and federal CCAP funds to counties (which the State refers to as LSSDs) based on historical program usage for each district. In turn, LSSDs must contribute a local share. The local share has been frozen since federal fiscal year 1997, and was calculated as equal to 25 percent of the costs of cases for families receiving public assistance. In fiscal year 2024 this local share totaled $68 million. New York City accounted for $53 million (78 percent) of the statewide local contribution. This local contribution was additive to $945 million in combined federal and state allocations in fiscal year 2024.

Once this local share is met, LSSDs can disburse funds up to their maximum State allocation. Any unused State funds can be rolled over into future years. At the end of federal fiscal year 2023, all LSSDs had a balance of unused funds, reflecting an ability to serve all qualifying families.[17]

CCAP is funded and implemented by multiple levels of government

Dollars are for fiscal year 2024

Recent CCAP reforms have increased eligibility and uptake

In recent years, New York has ramped up investment in CCAP, expanding the program to be nearly as expansive as possible under the federal rules. In fiscal year 2024, the State expanded CCAP eligibility to 85 percent of the state median income – the maximum allowable income under federal rules. The prior year, the State moved eligibility from 200 percent of the federal poverty measure to 300 percent – a level about 10 percent lower than the new, median income-based threshold. Together, these changes increased eligibility from just over one-quarter (27.2 percent) of New York households with children under the age of 6 to nearly half (45.5 percent).[18]

Further, in fiscal year 2023, the State increased the value of CCAP vouchers from the 69th percentile of market prices to the 80th percentile. Recent changes have also assigned higher voucher rates for childcare providers that meet established quality requirements above the requisite licensing requirements. Vouchers supporting homeless children and families and families working non-traditional hours also receive enhanced rates. Rate enhancements can increase voucher levels by 5 to 15 percent, at the discretion of LSSDs.

Finally, in recent years, the State has lowered the hours required to meet CCAP work requirements from 20 hours per week to 10 hours, expanded the educational programs exempt from work requirements, and reduced families’ required copayments, which had previously varied by LSSD, to 1 percent of income earned above the poverty measure.[19]

These expansions have increased families’ uptake of CCAP. The Covid pandemic was a severe setback for the childcare industry, forcing many providers to temporarily shutter and disrupting many families’ economic situations, affecting their demand for childcare. As a result, CCAP participation fell from 101,000 families in federal fiscal year 2019 to just 60,000 in federal fiscal year 2021. Program use remained depressed for the following year before surging to 80,000 in federal fiscal year 2023, the most recent year for which data is available.[20] Monthly use reports indicate that CCAP uptake has continued to accelerate, surpassing pre-Covid levels by early 2024.[21]

Recent reforms to CCAP

What’s next for CCAP

The State’s expansions to CCAP have incrementally expanded support for low- and middle-income families, reaching the maximum income eligibility threshold allowed under federal rules. Still, advocates point to additional steps that would facilitate greater access to childcare subsidies among currently-eligible families and expand eligibility to additional families.

First, lawmakers and advocates argue that delays in processing CCAP applications create a hardship for low-income workers. The establishment of presumptive eligibility, which would direct LSSDs to provide benefits to applicants while verifying eligibility, would overcome this challenge.[22]

Second, advocates argue that barriers remain for undocumented immigrants and for families who work non-traditional or irregular hours. CCAP requires that the hours of care match parents’ work hours, posing a challenge for those with jobs with fluctuating hours.[23] Proposed legislation would decouple care hours from hours worked.[24] Further legislation would remove CCAP’s requirement that applicants earn at least the minimum wage, a requirement that may bar families working irregular jobs.[25]

Finally, advocates challenge the validity of the market survey used to set CCAP voucher rates. Advocates argue that the market survey captures the prices of a market that depends on paying its workers inadequate wages. An alternative method for setting voucher prices would estimate the costs of providing childcare, calculating the prices of inputs, including rent and wages, for each region. The cost modeling approach is allowed under federal rules, and currently used by New Mexico and DC.[26]

Supplementing childcare worker wages

The inadequate wages paid to childcare workers is a longstanding challenge. Low wages hurt workers and make it difficult for childcare providers to attract and retain staff. In fiscal year 2024, the State took the unprecedented step of making wage supplement payments to childcare workers. The State appropriated $500 million in federal Covid relief funding for one-time payments of up to $3,000 per worker to childcare workers.[27] At the end of the year, having disbursed awards to all qualified applicants, $150 million of these funds were left over. In fiscal year 2025, the State appropriated $280 million in unused federal funds for a second round of payments. Importantly, these payments are temporary and funded with temporary resources, rather than a recurring State-funded commitment. Further, providers must apply for these payments, and low awareness may hinder program reach. Advocates have called for a permanent $1.2 billion fund to provide each childcare worker with a $12,500 annual wage supplement.[28]

Other State-led childcare initiatives

The State also launched two small-scale programs to support childcare in fiscal year 2024: 1) a pilot to sponsor employer-provided childcare and 2) a tax credit for childcare expansions. The $5 million employer-supported childcare pilot would sponsor childcare centers that split costs between the State, employers, and parents, making services available to those earning between 85 and 100 percent of the state median income – just above CCAP eligibility. The State has been slow to roll out this initiative.[29] Second, the State established the $50 million Child Care Creation and Expansion Tax Credit, which offsets the business tax liability of childcare providers that create new capacity in 2023 or 2024.

The future of New York’s childcare

Despite recent progress, the unaffordability of childcare remains a significant challenge for New York families. Only a small share of New Yorkers were affected by recent changes, and recent changes have had no effect on families above the CCAP eligibility threshold. Still, childcare costs continue to weigh on many working and middle-income families. For this reason, policymakers have begun exploring alternative models for childcare that go beyond the existing CCAP subsidies and establish universal access to affordable childcare in New York.

While barriers to CCAP benefits remain, the program is approaching its maximum reach allowed under federal regulations. This limits the State’s ability to support moderate-income families in need of childcare. In particular, the federally-imposed income limit of 85 percent of State median income creates a sharp benefits cliff. A middle-income family earning just above this limit ($91,251 for a family of three) would entirely lose access to CCAP benefits, a loss of as much as $21,000. Expansions to childcare support for middle-income families, therefore, would require entirely State-funded programs working in parallel with the federally-backed CCAP.

In 2018, Governor Cuomo established a task force composed of public officials, advocates and researchers, labor, childcare providers, and other stakeholders to study the availability and accessibility of childcare throughout the state and make recommendations for addressing any shortcomings. The task force was extended in 2021 and released its second annual final report in April 2024.[30] The 2024 report included recommendations to permanently supplement workers’ wages and provide workforce development support; continue to expand CCAP, including by adopting cost modeling; and increase the supply of quality childcare providers. Finally, the task force is set to release a report by the end of 2024 outlining a roadmap to statewide universal childcare.

While the task force avoided making concrete recommendations for universal childcare, instead putting forward guidelines for planning such a policy, it did recommend creating a pilot program to test the feasibility of universal childcare, gather data on program use, and provide insight on policy design. This recommendation is advanced by a bill recently introduced in the New York State Senate that would establish twenty pilot locations for childcare centers offering universal admissions fully funded by the State.[31]

This work continues policy advocacy launched in 2022 when two bills proposed establishing statewide universal childcare.[32] While neither bill was adopted, advocates have increasingly pushed to continue incremental expansions in the State’s support for childcare with the goal of building a system of universal affordable coverage.[33]

[1] https://www.dol.gov/agencies/wb/topics/featured-childcare

[2] https://www.dol.gov/agencies/wb/topics/childcare/price-by-age-care-setting

[3] https://fiscalpolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/FPI-Migration-Pt-2.pdf

[4] https://ocfs.ny.gov/programs/childcare/regulations/418-1-DCC.pdf

[5] https://ecommons.cornell.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/71c61a1c-d893-4804-abff-41e618634bd2/content

[6] https://ocfs.ny.gov/programs/childcare/assets/docs/factsheets/2023-DCCS-Fact-Sheet.pdf; https://ocfs.ny.gov/programs/childcare/assets/docs/factsheets/2019-DCCS-Fact-Sheet.pdf

[8] https://fiscalpolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/FPI-FY-2024-Budget-Briefing-Book.pdf

[9] https://ocfs.ny.gov/programs/childcare/assets/docs/factsheets/2023-DCCS-Fact-Sheet.pdf. CCAP enrollment includes eligible children under the age of 13. Nevertheless, the large majority of CCAP is for children under six, who have not yet enrolled in kindergarten.

[10] https://ocfs.ny.gov/main/policies/external/2024/lcm/24-OCFS-LCM-22.pdf

[11] https://www.nyc.gov/site/acs/early-care/apply-child-care.page

[12] https://ocfs.ny.gov/programs/childcare/regulations/415-Child-Care-Services.pdf

[13] https://www.acf.hhs.gov/occ/data/gy-2024-ccdf-allocations-based-appropriations

[14] https://scaany.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Schuyler-Center-Last-Look-2024-25-Enacted-Budget-04302024.pdf

[15] https://www.budget.ny.gov/pubs/archive/fy21/enac/fy21-enacted-fp.pdf; This value is primarily comprised of CCAP, although other smaller childcare initiatives are included.

[16] https://www.budget.ny.gov/pubs/archive/fy25/en/fy25fp-en.pdf

[17] https://ocfs.ny.gov/main/policies/external/2023/lcm/23-OCFS-LCM-12-R3.pdf

[18] https://fiscalpolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/FPI-FY-2024-Budget-Briefing-Book.pdf

[19] https://ocfs.ny.gov/main/policies/external/ocfs_2021/ADM/21-OCFS-ADM-30.pdf

[20] https://ocfs.ny.gov/programs/childcare/data/

[21] https://ocfs.ny.gov/programs/childcare/assets/docs/ccap/NYCCAP-Family-Child-Counts-2024May.pdf

[22] (A.4099 (Clark)/ S.4667 (Brouk)

[23] https://empirestatechildcare.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Removing-Barriers-1-Pager.pdf

[24] https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/bills/2023/S5327/amendment/A

[25] (A.1303 (Clark)/S.4924(Ramos)

[26] https://www.americanprogress.org/article/states-can-improve-child-care-assistance-programs-through-cost-modeling/

[27] Grants are only available to childcare workers in caring roles who work at least 15 hours per week. https://ocfs.ny.gov/programs/childcare/grants/workforce-grant/

[28] https://empirestatechildcare.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/NEW-Updated-2024-Post-Budget-Priorities.pdf

[29] https://capitolpressroom.org/2024/04/23/hochul-administration-slow-to-realize-touted-child-care-initiatives/

[30] https://ocfs.ny.gov/programs/childcare/availability/CCATF-Relaunch-Legislation.pdf

[31] https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/bills/2023/S9853

[32] https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/bills/2023/S3245; https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/bills/2021/s7615

[33] https://empirestatechildcare.org/what-is-universal-child-care/victories-on-the-path-to-universal-child-care/