Budget Breakdown: Fiscal Year 2026 Enacted Budget

May 14, 2025 |

New York State’s fiscal year 2026 budget was signed into law on May 9, more than a month after the official April 1st deadline. The delay resulted from Governor Hochul’s inclusion of criminal justice priorities in the negotiation process, which left legislators with only a few days to discuss the significant fiscal risks facing the State.

The Enacted Budget, while it contains few significant new policy initiatives, does commit to planned increases in major spending categories, namely education and healthcare, allowing the budget to recover some of the lost ground from a decade of austerity policies in the 2010s. The most important policy measure in the budget is a long overdue increase in unemployment insurance benefits that will better prepare the State economy for a possible recession (discussed in detail below).

The bad news is that the Enacted Budget contains serious fiscal errors, including permanent tax cuts and one-time payments that will cost $3 billion in fiscal year 2026 alone. This is unwise fiscal management in any year, and particularly irresponsible this year, when the State is sure to lose substantial federal funding.

Even more concerning, the Enacted Budget authorizes the Budget Director to withhold spending in the event of a General Fund imbalance of $2 billion or more. This authorization essentially forfeits the Legislature’s responsibility to determine how spending cuts should be implemented (or else avoided through tax increases) in the event of a recession or significant funding shortfalls.

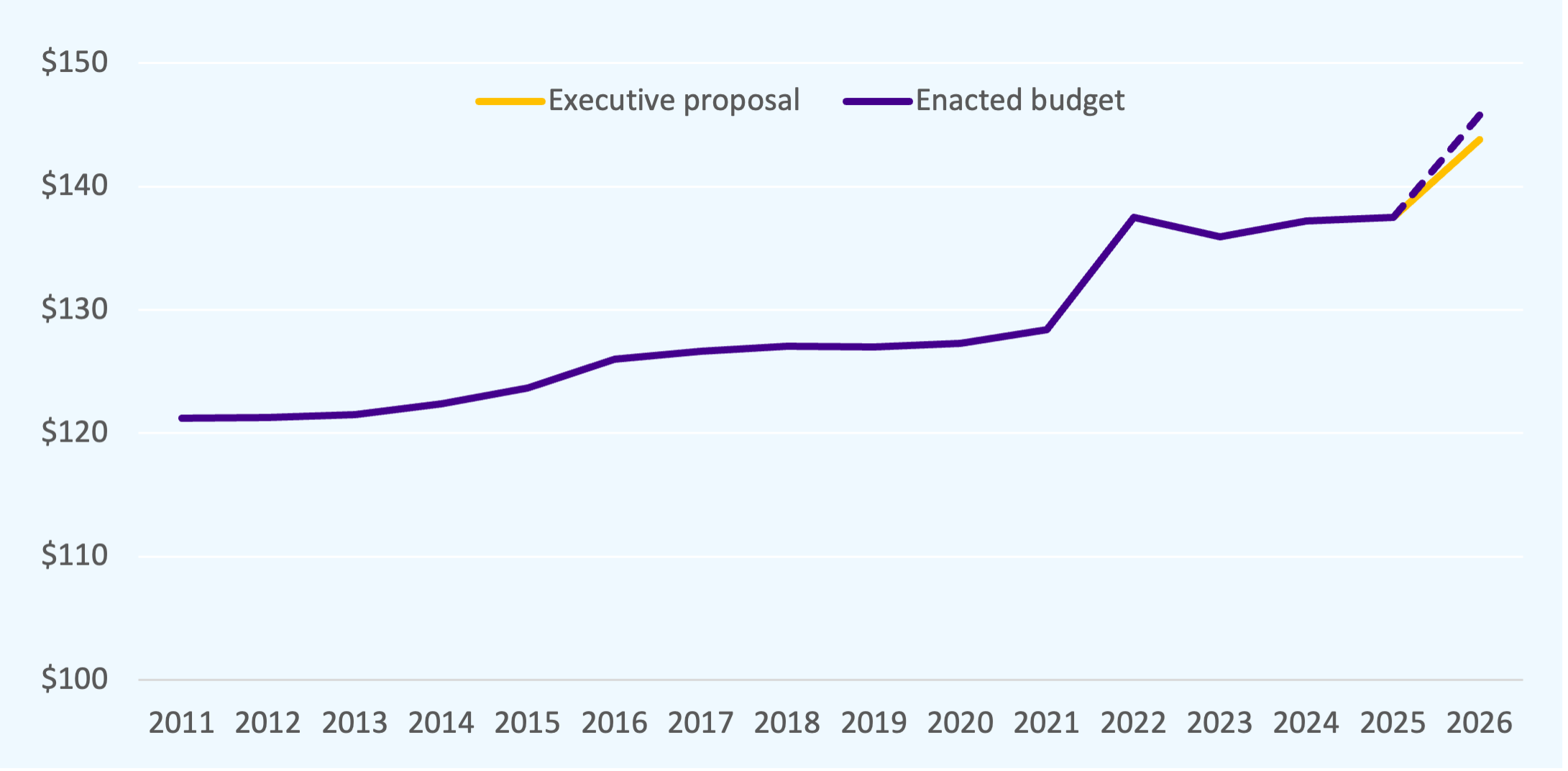

The Enacted Budget totals $254 billion, just $2 billion higher than proposed in the Governor’s Executive Budget from January. This represents an increase over last year’s budget of $8.8 billion in state spending, and an inflation-adjusted increase of 6 percent. Measuring the budget in dollars, or even inflation-adjusted dollars, however, fails to provide an accurate picture of overall budgetary growth.

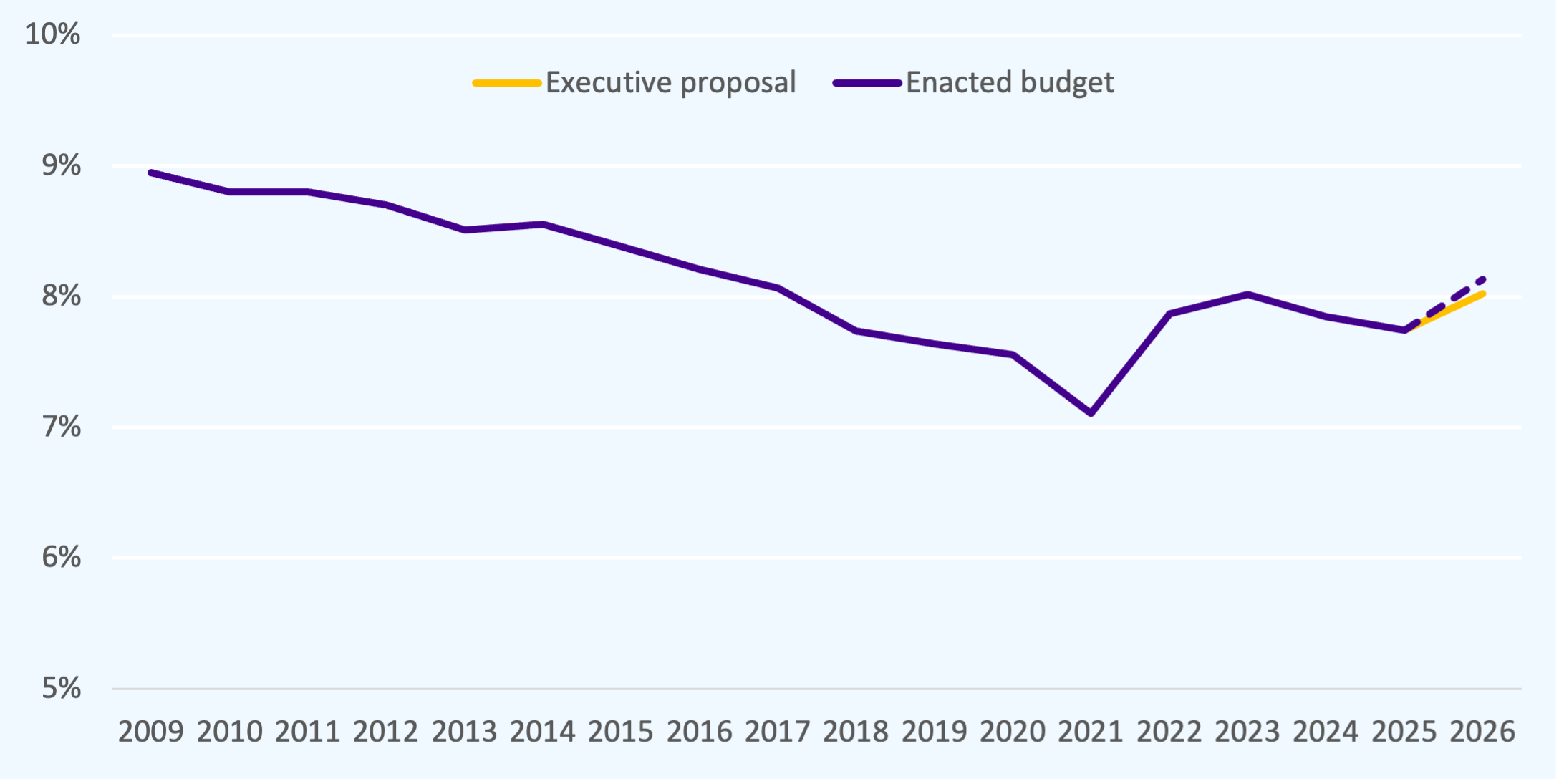

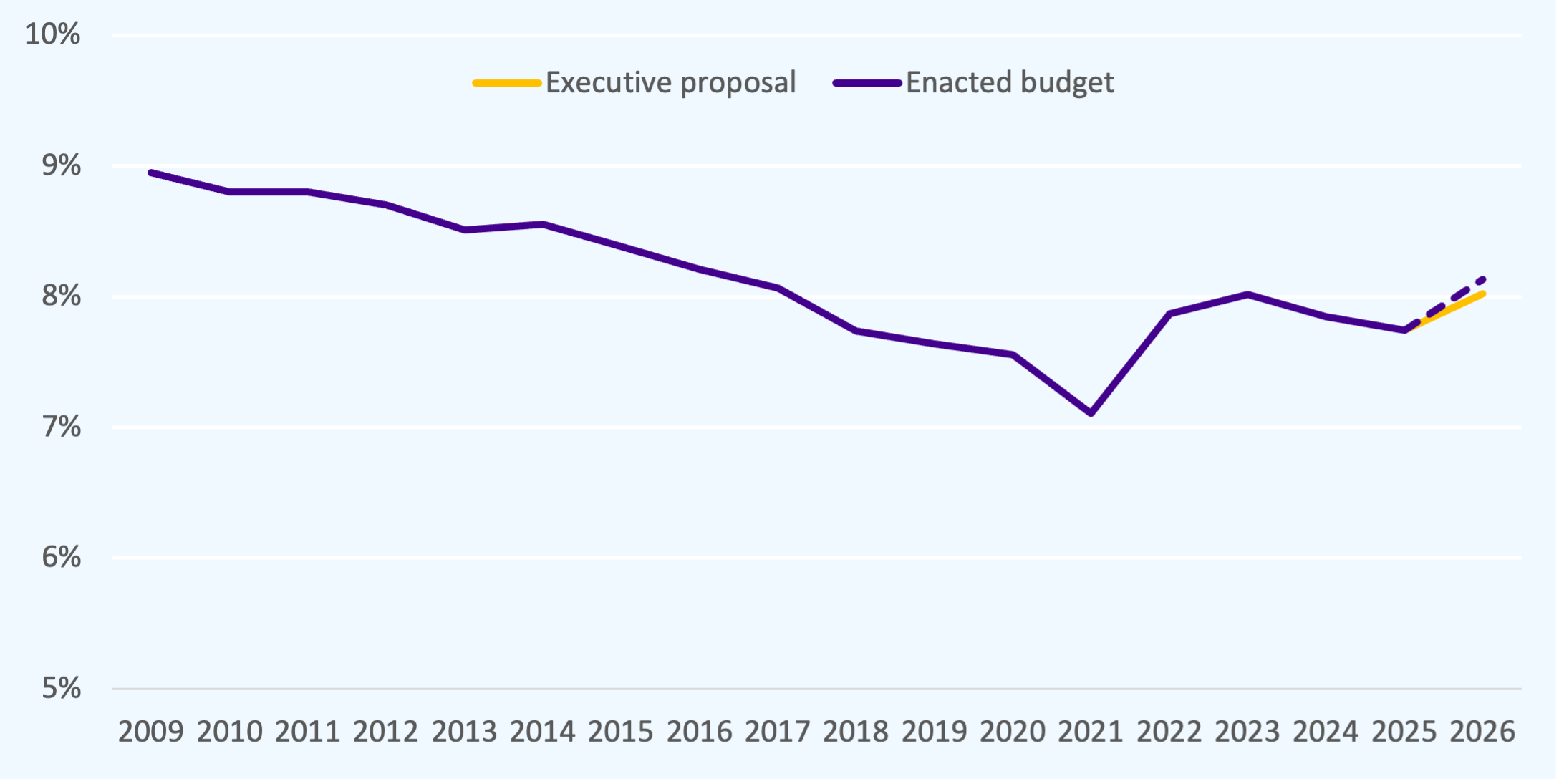

The budget should be understood in relation to the New York State economy, which determines the total capacity of the State government to finance public services and investment. Measured in these terms, State spending fell from its share of 9 percent of state personal income (a gauge of overall state economic activity) in fiscal year 2009 to 7 percent in 2021 amid a decade-long policy of fiscal austerity, underinvestment, and cost shifting onto local governments. In fiscal year 2026, the budget is set to reach just over 8 percent. This puts the State budget’s relative size on par with fiscal year 2017.

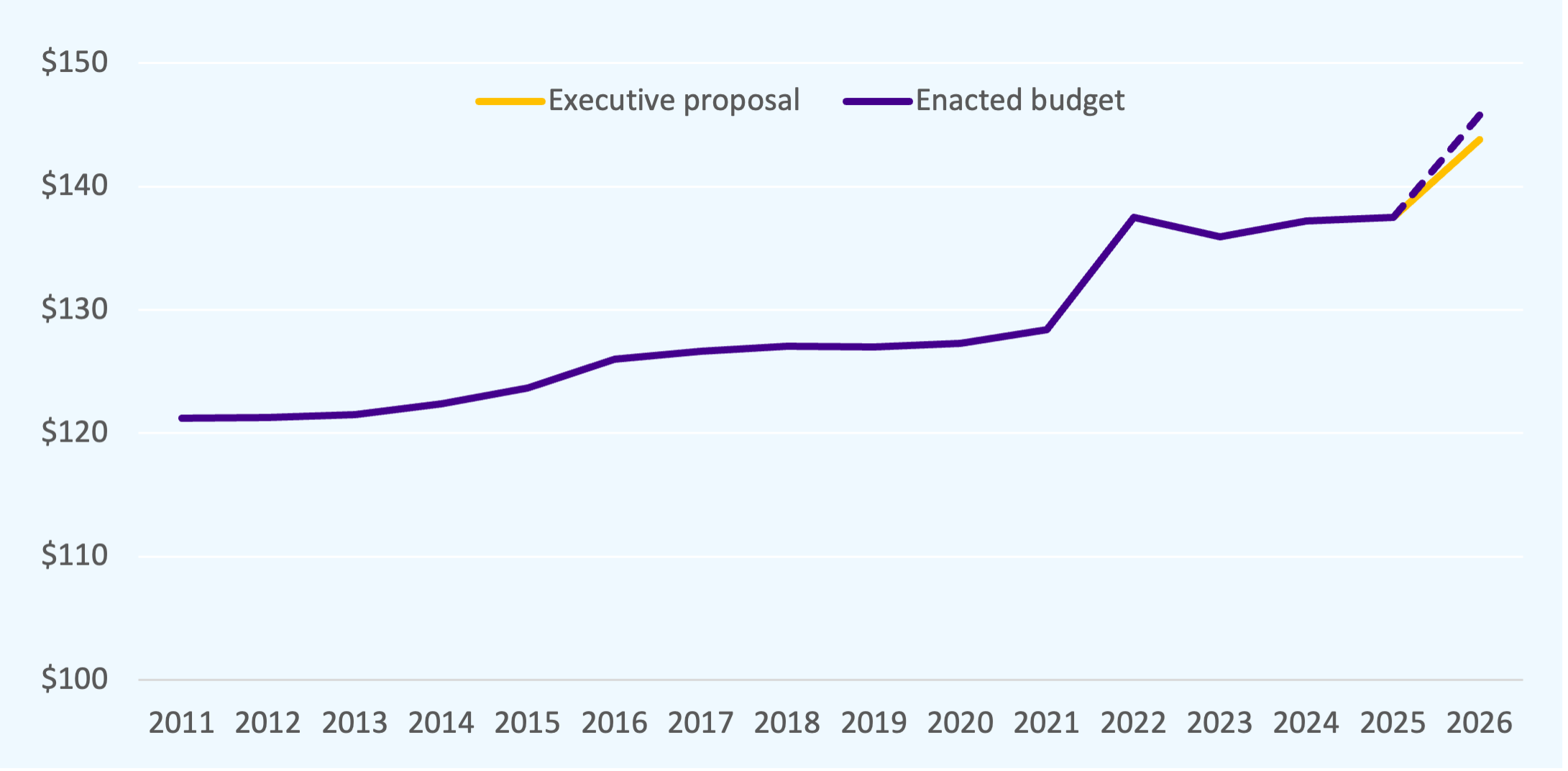

State operating funds spending, adjusted for inflation, fiscal years 2011 to 2026

Billions of dollars, adjusted to fiscal year 2025 dollars

State operating funds spending as a share of state personal income, fiscal years 2009 to 2026

Percent of total New York personal income

Other Fiscal Issues

- Reserves: The State currently has $34 billion in reserves — more than at any time in its history.[1]

- These resources include $22 billion in formal reserves and $12 billion in undesignated balances available to support the budget

- The State’s strong reserve balances will allow it to continue to fund services through an economic downturn or loss of federal funding

- Budget gaps: The State’s forecasted budget gaps are primarily the result of conservative revenue projections.

- The gaps projected by the executive budget—$6.5 billion in fiscal year 2027, rising to $11 billion by fiscal year 2029—are within the range typically considered “manageable,” as they are generally closed when revenue exceeds the State’s overly-cautious forecasts.

- If revenue grows in line with its average rate over the 2010s and the state extends corporate tax rates that are set to fall in 2027, gaps would average just $1 billion annually.

Issue Focus: Unemployment Insurance

The Enacted Budget includes one major accomplishment that will generate significant material benefits for New York workers: a deal to improve unemployment insurance benefits (UI) and pay off New York’s long-held UI trust fund debt to the federal government, which had raised taxes on employers.

New York’s Unemployment Insurance (UI) program has long needed reform: benefit levels have been too low to achieve economic stability in a downturn, and too many workers are excluded from the scope of the program. The high volume of unemployment claims during the Covid-19 pandemic forced the State to borrow substantial sums from the federal government in order to pay claims; now, the State owes the federal government a debt of $6.4 billion, and until that debt is paid down (and additional funding contributed to make the State’s trust fund solvent), benefits will remain at below-poverty levels.

This year’s budget negotiations included a major deal between labor representatives and business interests; the deal included the following changes:

- The State will use reserves to pay off the nearly $6.5 billion of debt with the federal government and return the UI trust fund to solvency. By doing so, the State will “un-freeze” the maximum benefit level paid to unemployed workers and prevent an incremental increase — about $300 per employee annually — in the payroll tax rate levied on employers that pays for the program;

- The maximum weekly benefit paid to unemployed workers will increase from $504, the rate at which it’s been frozen since 2019, to $869 on the first Monday in October 2025 — a 72 percent increase in the weekly benefit that will result in an additional payout of $1,500 per month for workers seeking the maximum benefit. This increase in the maximum benefit will occur regardless of whether the fund is solvent as of October 2025;

- The payroll tax the funds the UI program was slightly increased. Specifically, the amendment to the UI law increased taxable wages from 16 percent of the state’s average annual wage (about $14,700) to 18 percent of the state’s average annual wage (about $16,600). This change will result in a revenue increase to the State of approximately $450 million annually and will likely increase the tax on most employees by less than $100 per employee annually; and

- Striking workers can now access unemployment benefits after a single week of being on strike. Previously, striking workers had to be on strike for over two weeks before being eligible for unemployment insurance benefits.

By increasing benefits significantly for workers, the deal struck in this year’s budget will not only prevent unemployed workers from potentially falling into poverty during unemployment spells, but it will also stabilize the State’s macro-economy.

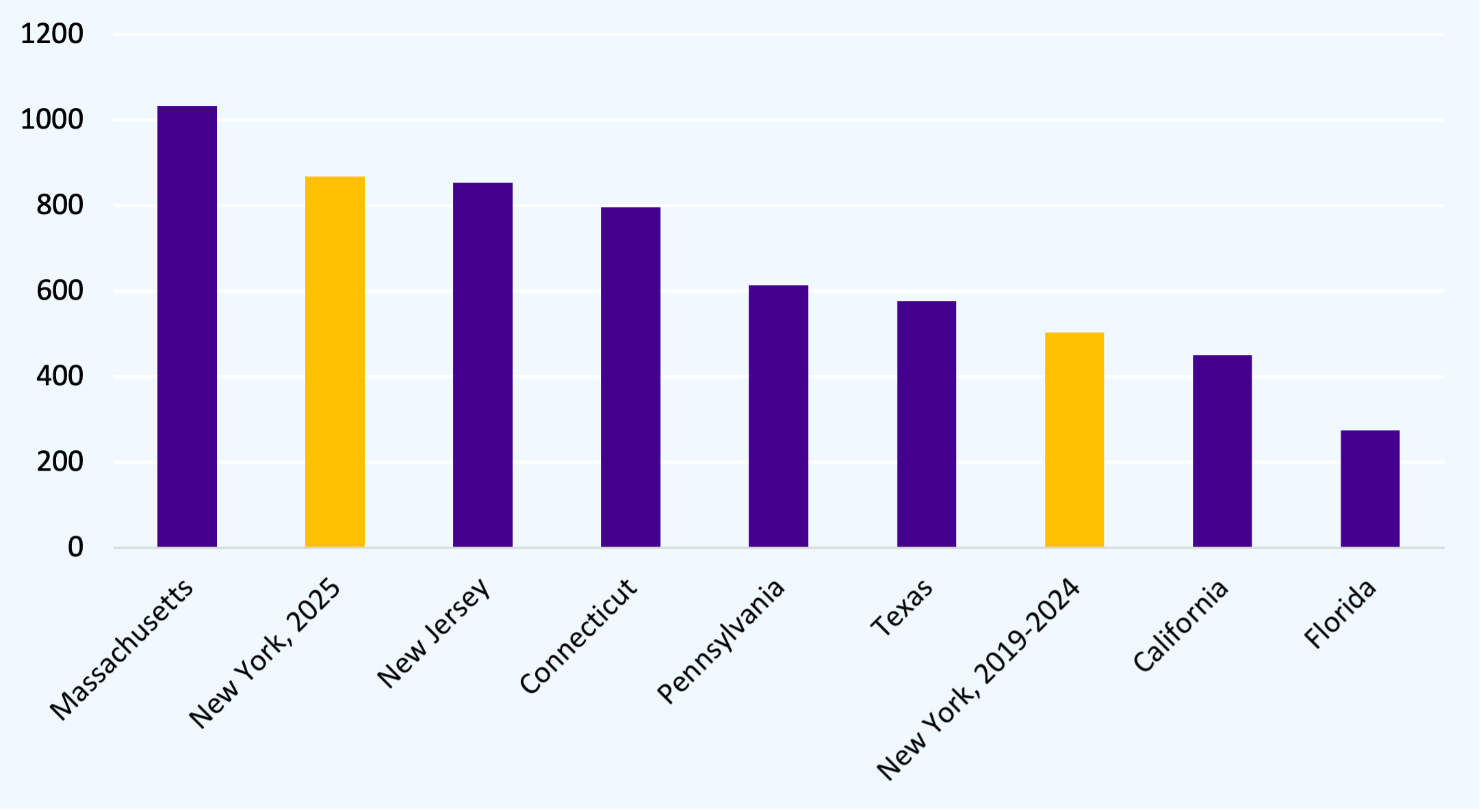

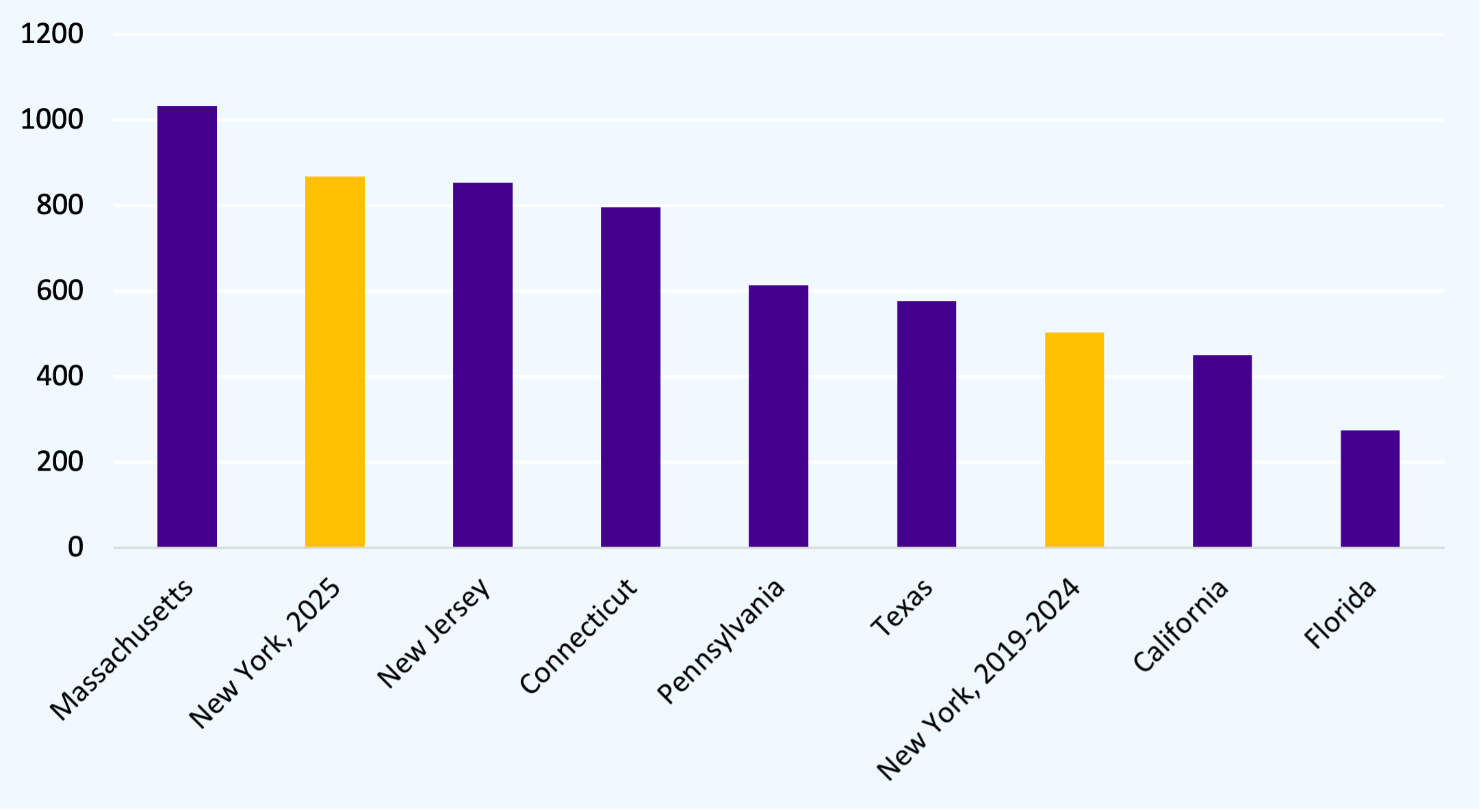

Maximum weekly UI benefit, by State

[1] This includes unrestricted general fund balances, but excludes PTET and labor agreement reserves. Fiscal year 2025 executive budget financial plan and March 2024 State Comptroller monthly cash basis report.

Summary of Enacted Budget Provisions

Healthcare Policy

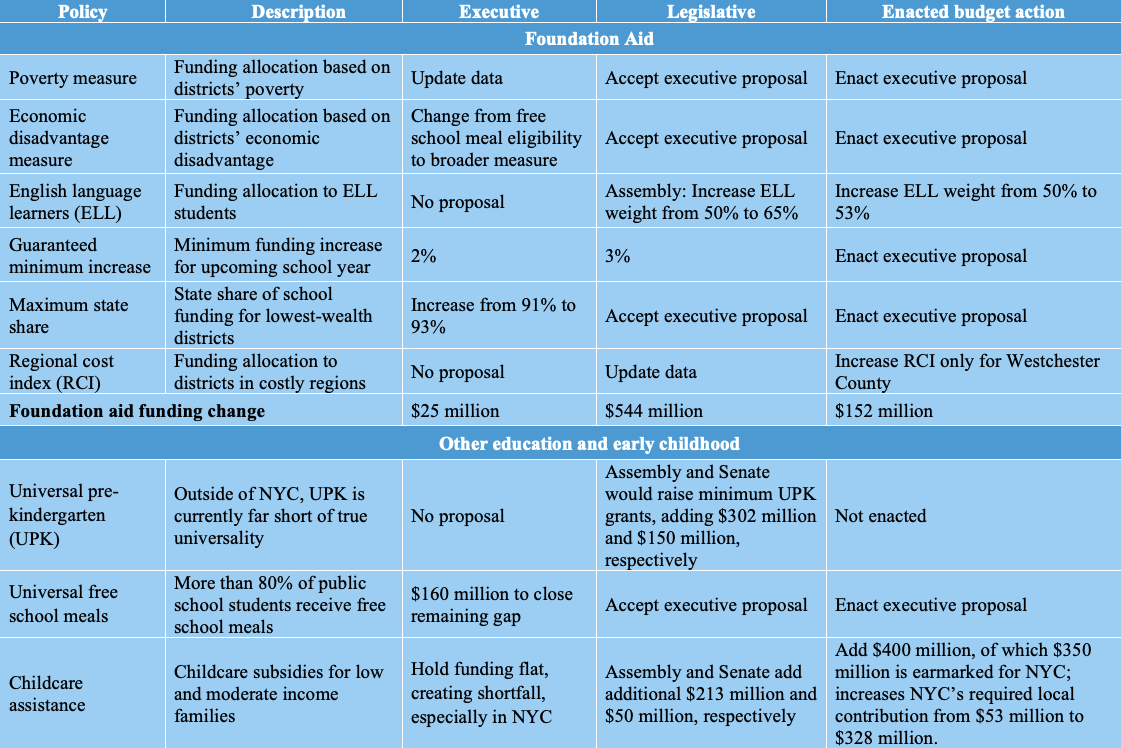

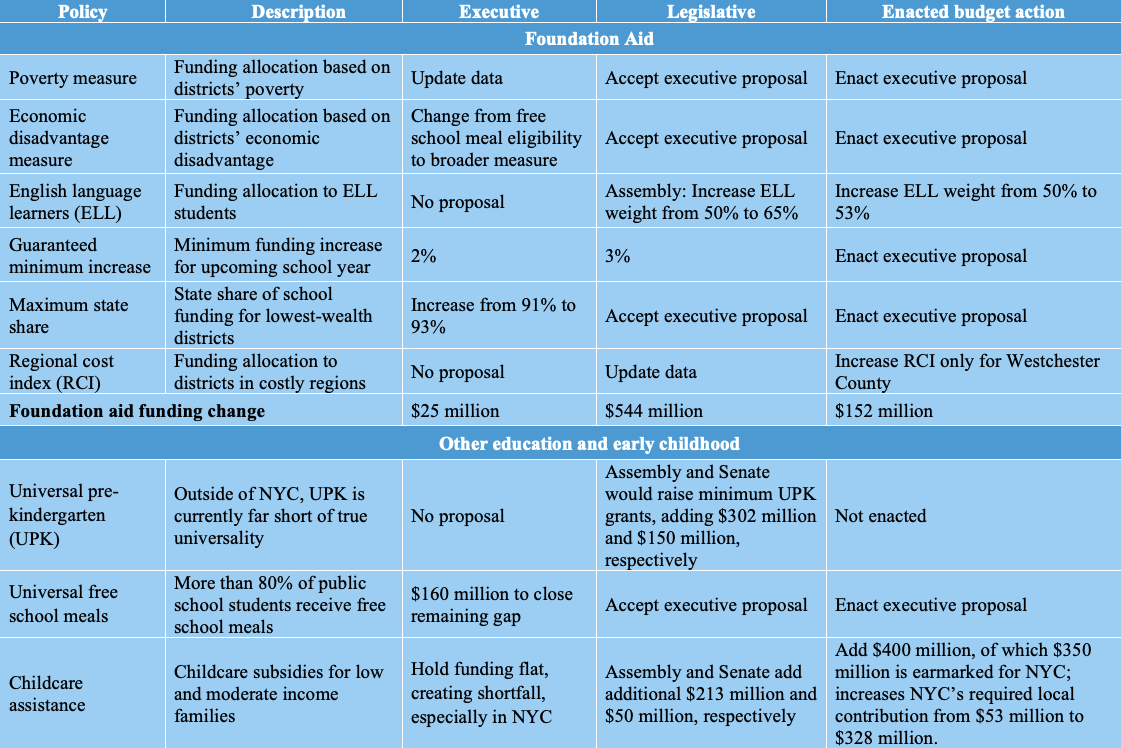

Education and Childcare Policy

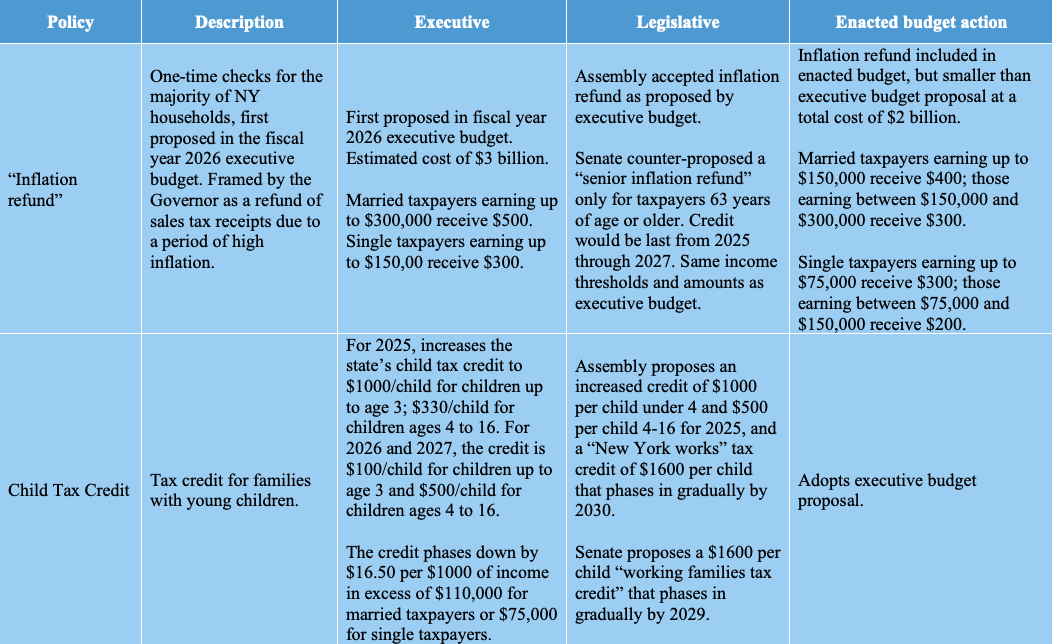

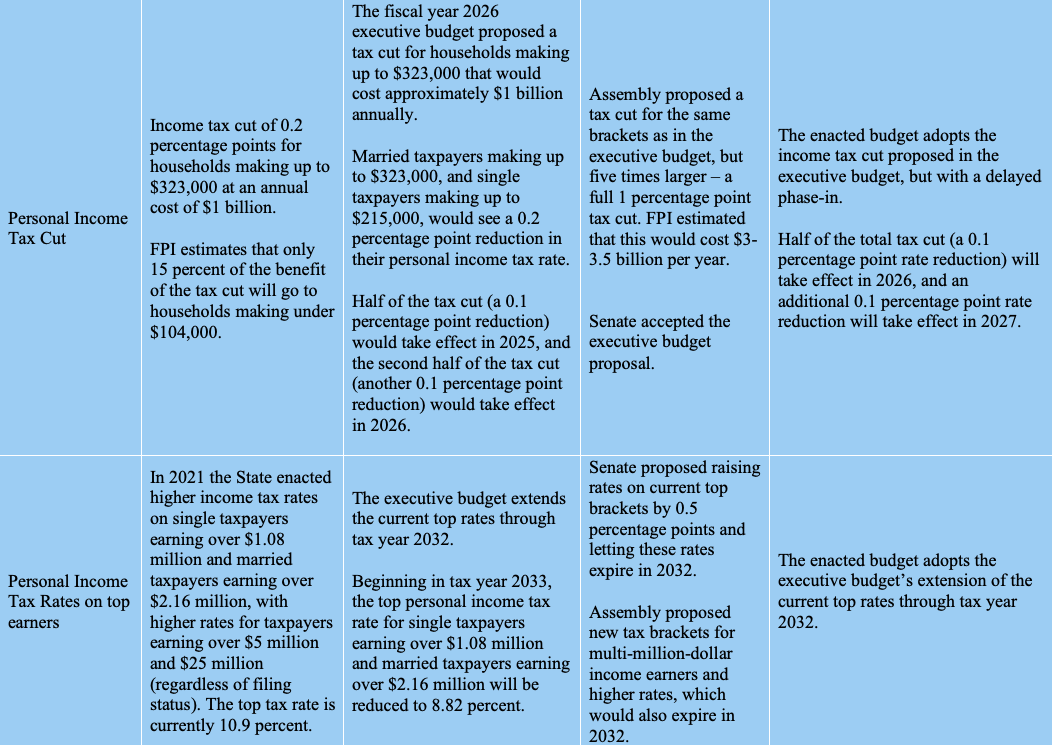

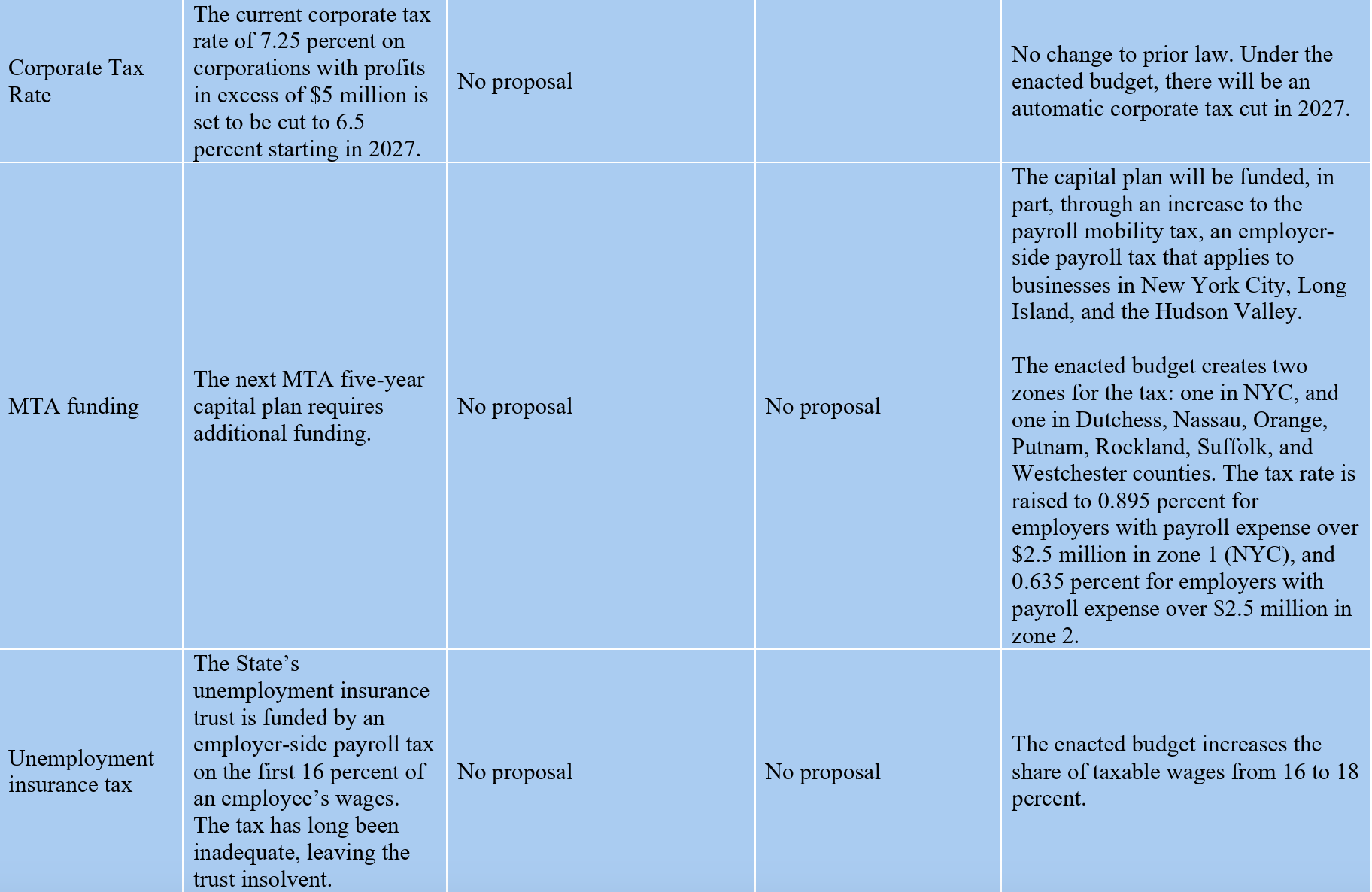

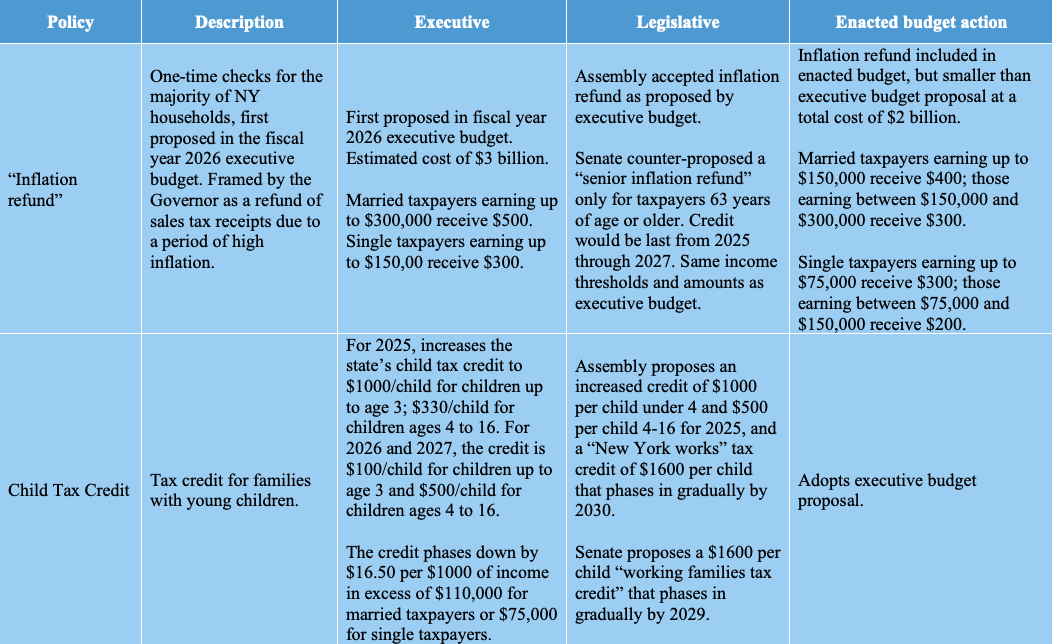

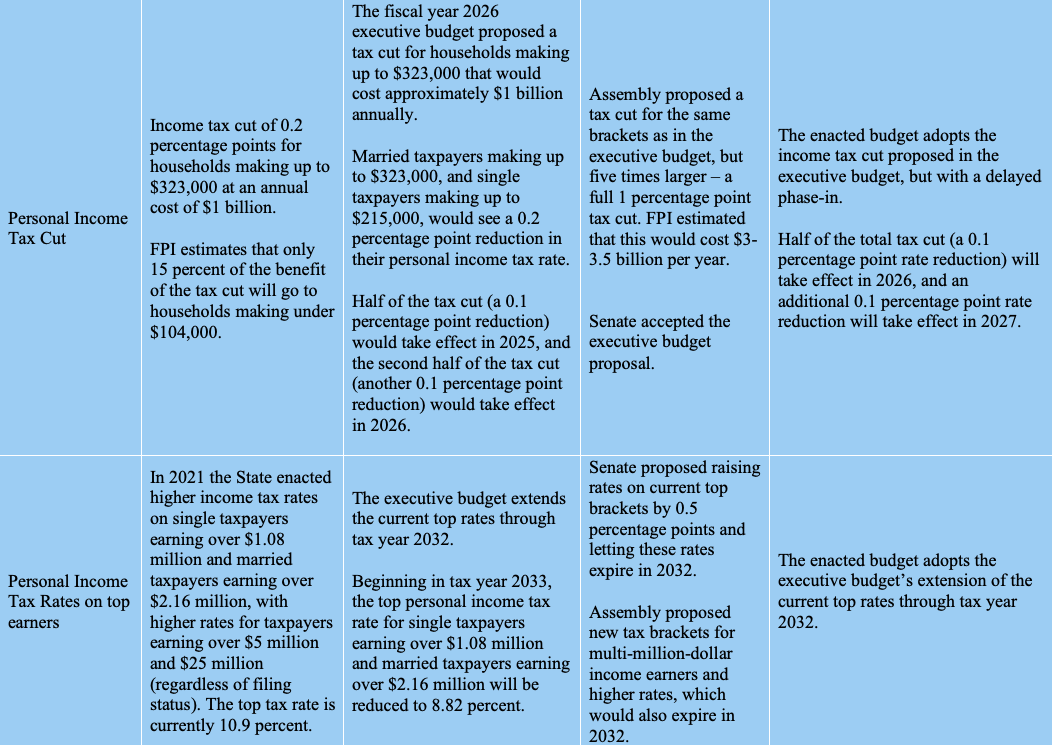

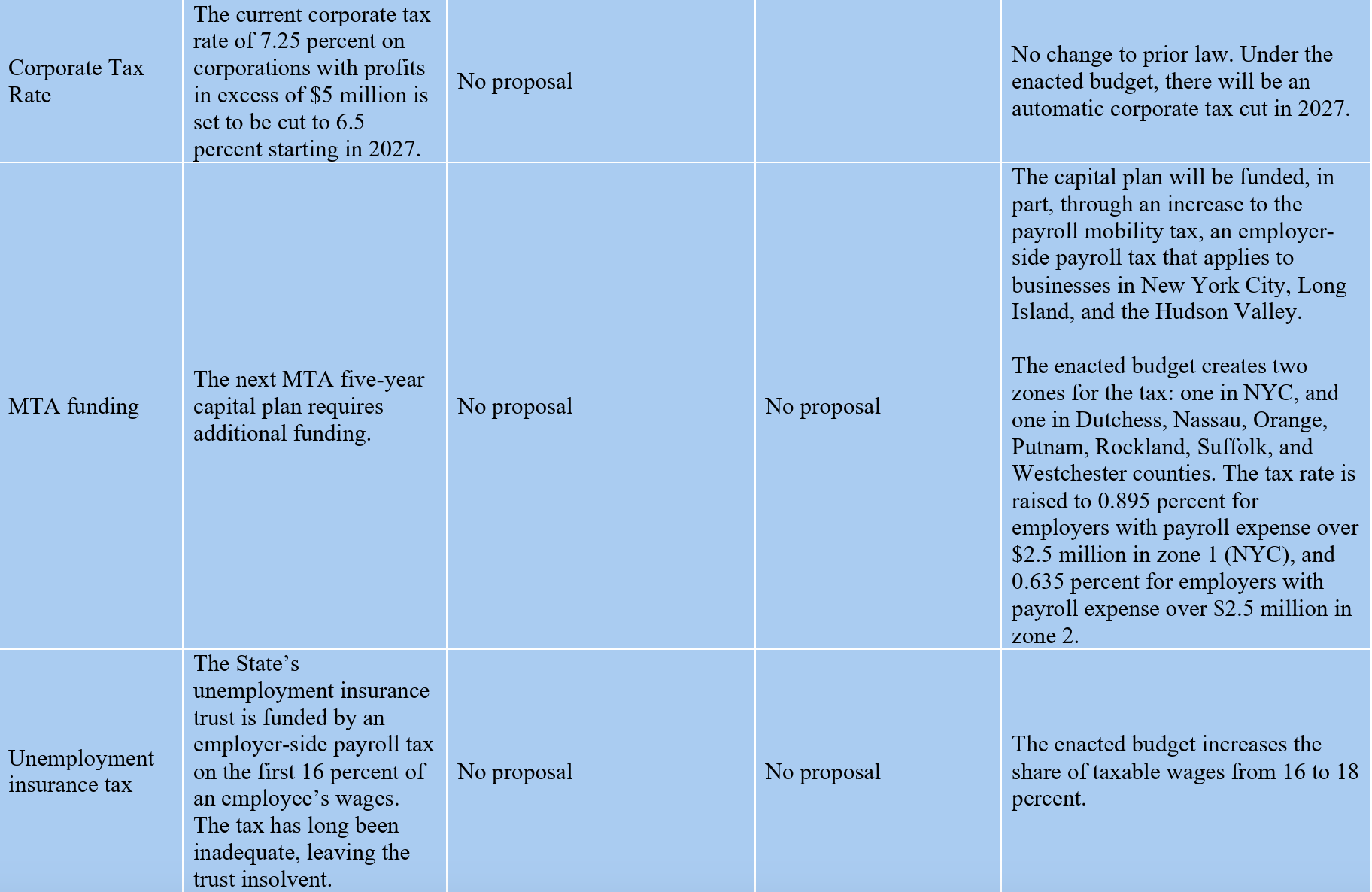

Tax Policy

Housing Policy

Budget Breakdown: Fiscal Year 2026 Enacted Budget

May 14, 2025 |

New York State’s fiscal year 2026 budget was signed into law on May 9, more than a month after the official April 1st deadline. The delay resulted from Governor Hochul’s inclusion of criminal justice priorities in the negotiation process, which left legislators with only a few days to discuss the significant fiscal risks facing the State.

The Enacted Budget, while it contains few significant new policy initiatives, does commit to planned increases in major spending categories, namely education and healthcare, allowing the budget to recover some of the lost ground from a decade of austerity policies in the 2010s. The most important policy measure in the budget is a long overdue increase in unemployment insurance benefits that will better prepare the State economy for a possible recession (discussed in detail below).

The bad news is that the Enacted Budget contains serious fiscal errors, including permanent tax cuts and one-time payments that will cost $3 billion in fiscal year 2026 alone. This is unwise fiscal management in any year, and particularly irresponsible this year, when the State is sure to lose substantial federal funding.

Even more concerning, the Enacted Budget authorizes the Budget Director to withhold spending in the event of a General Fund imbalance of $2 billion or more. This authorization essentially forfeits the Legislature’s responsibility to determine how spending cuts should be implemented (or else avoided through tax increases) in the event of a recession or significant funding shortfalls.

The Enacted Budget totals $254 billion, just $2 billion higher than proposed in the Governor’s Executive Budget from January. This represents an increase over last year’s budget of $8.8 billion in state spending, and an inflation-adjusted increase of 6 percent. Measuring the budget in dollars, or even inflation-adjusted dollars, however, fails to provide an accurate picture of overall budgetary growth.

The budget should be understood in relation to the New York State economy, which determines the total capacity of the State government to finance public services and investment. Measured in these terms, State spending fell from its share of 9 percent of state personal income (a gauge of overall state economic activity) in fiscal year 2009 to 7 percent in 2021 amid a decade-long policy of fiscal austerity, underinvestment, and cost shifting onto local governments. In fiscal year 2026, the budget is set to reach just over 8 percent. This puts the State budget’s relative size on par with fiscal year 2017.

State operating funds spending, adjusted for inflation, fiscal years 2011 to 2026

Billions of dollars, adjusted to fiscal year 2025 dollars

State operating funds spending as a share of state personal income, fiscal years 2009 to 2026

Percent of total New York personal income

Other Fiscal Issues

- Reserves: The State currently has $34 billion in reserves — more than at any time in its history.[1]

- These resources include $22 billion in formal reserves and $12 billion in undesignated balances available to support the budget

- The State’s strong reserve balances will allow it to continue to fund services through an economic downturn or loss of federal funding

- Budget gaps: The State’s forecasted budget gaps are primarily the result of conservative revenue projections.

- The gaps projected by the executive budget—$6.5 billion in fiscal year 2027, rising to $11 billion by fiscal year 2029—are within the range typically considered “manageable,” as they are generally closed when revenue exceeds the State’s overly-cautious forecasts.

- If revenue grows in line with its average rate over the 2010s and the state extends corporate tax rates that are set to fall in 2027, gaps would average just $1 billion annually.

Issue Focus: Unemployment Insurance

The Enacted Budget includes one major accomplishment that will generate significant material benefits for New York workers: a deal to improve unemployment insurance benefits (UI) and pay off New York’s long-held UI trust fund debt to the federal government, which had raised taxes on employers.

New York’s Unemployment Insurance (UI) program has long needed reform: benefit levels have been too low to achieve economic stability in a downturn, and too many workers are excluded from the scope of the program. The high volume of unemployment claims during the Covid-19 pandemic forced the State to borrow substantial sums from the federal government in order to pay claims; now, the State owes the federal government a debt of $6.4 billion, and until that debt is paid down (and additional funding contributed to make the State’s trust fund solvent), benefits will remain at below-poverty levels.

This year’s budget negotiations included a major deal between labor representatives and business interests; the deal included the following changes:

- The State will use reserves to pay off the nearly $6.5 billion of debt with the federal government and return the UI trust fund to solvency. By doing so, the State will “un-freeze” the maximum benefit level paid to unemployed workers and prevent an incremental increase — about $300 per employee annually — in the payroll tax rate levied on employers that pays for the program;

- The maximum weekly benefit paid to unemployed workers will increase from $504, the rate at which it’s been frozen since 2019, to $869 on the first Monday in October 2025 — a 72 percent increase in the weekly benefit that will result in an additional payout of $1,500 per month for workers seeking the maximum benefit. This increase in the maximum benefit will occur regardless of whether the fund is solvent as of October 2025;

- The payroll tax the funds the UI program was slightly increased. Specifically, the amendment to the UI law increased taxable wages from 16 percent of the state’s average annual wage (about $14,700) to 18 percent of the state’s average annual wage (about $16,600). This change will result in a revenue increase to the State of approximately $450 million annually and will likely increase the tax on most employees by less than $100 per employee annually; and

- Striking workers can now access unemployment benefits after a single week of being on strike. Previously, striking workers had to be on strike for over two weeks before being eligible for unemployment insurance benefits.

By increasing benefits significantly for workers, the deal struck in this year’s budget will not only prevent unemployed workers from potentially falling into poverty during unemployment spells, but it will also stabilize the State’s macro-economy.

Maximum weekly UI benefit, by State

[1] This includes unrestricted general fund balances, but excludes PTET and labor agreement reserves. Fiscal year 2025 executive budget financial plan and March 2024 State Comptroller monthly cash basis report.

Summary of Enacted Budget Provisions

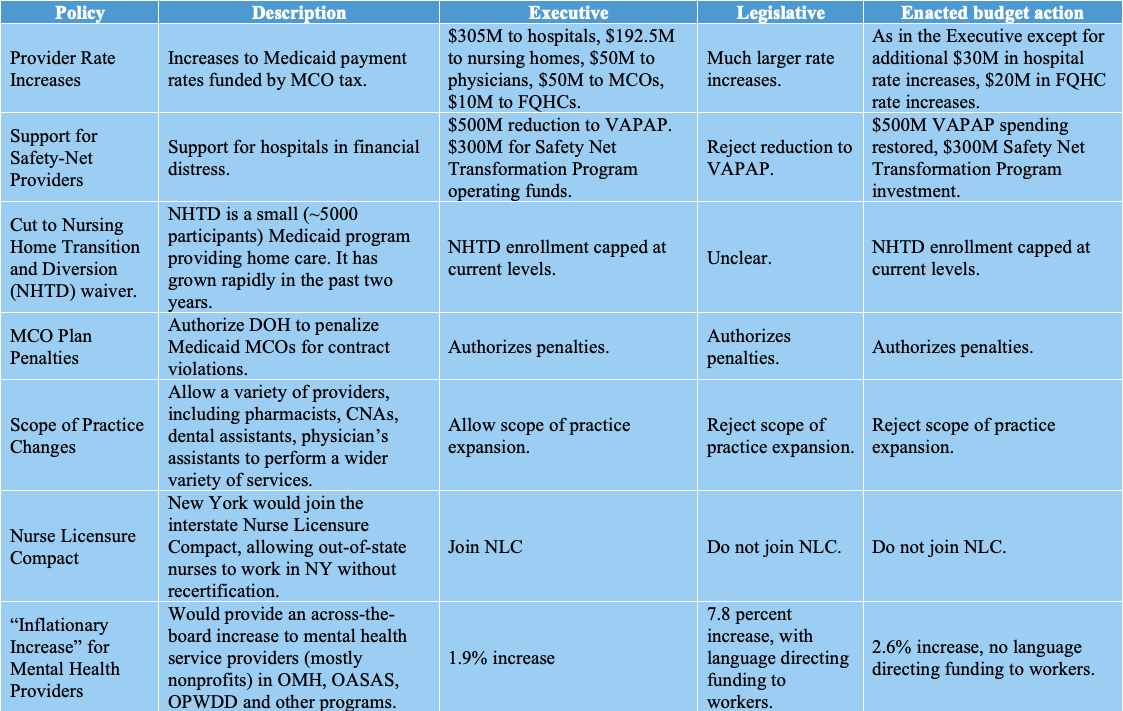

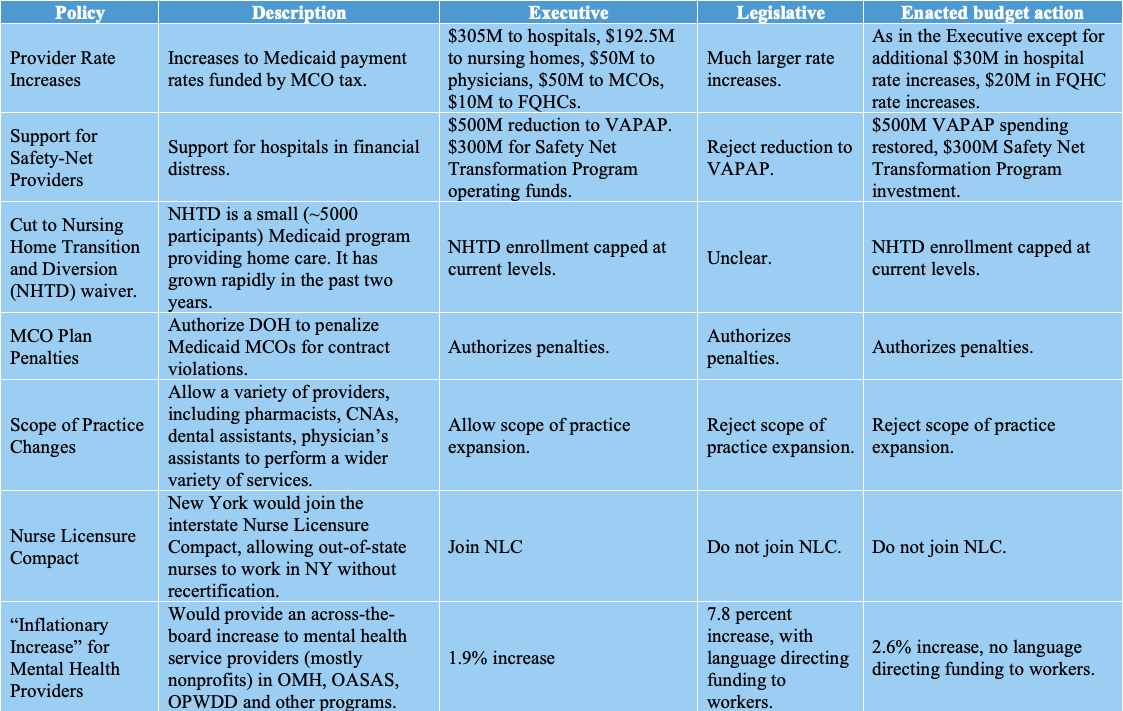

Healthcare Policy

Education and Childcare Policy

Tax Policy

Housing Policy