City Council’s Housing Bills Would Make Housing Less Affordable

December 11, 2025 |

Executive Summary

- The City Council will likely vote next week on a series of “term sheet bills” that would legislate new rigid restrictions on city-financed affordable housing development and preservation.

- Int 1433-2025: A bill that requires all housing projects receiving public subsidy from the City to contain a minimum share of two- and three-bedroom apartments;

- Int 1437-2025: A bill that would cap the number of studio apartments in city-subsidized senior housing; and

- Int 1443-2025: A bill that would require that half of all income-restricted units in city-subsidized housing be targeted at households making no more than 50 percent of the “area median income” (AMI).

- These bills, though well-intentioned, will drive up the cost of developing new affordable housing in the city and put major obstacles in the way of the incoming Mayor’s affordable housing agenda.

- The bills will significantly reduce the number of overall affordable units that the City can develop by driving up costs and making the housing development pipeline more complex.

- Particularly in the context of cuts to federal Section 8 funding, these bills will limit the capacity of New York City to develop housing that is affordable for low- and middle-income families

This week, City Council will consider a series of bills that would put major new constraints on city-financed affordable housing. The bills are:

• Int 1433-2025: A bill that requires all housing projects receiving public subsidy from the City to contain a minimum share of two- and three-bedroom apartments;

• Int 1437-2025: A bill that would cap the number of studio apartments in City-subsidized senior housing; and

• Int 1443-2025: A bill that would require that half of all income-restricted units in city-subsidized housing be targeted at households making no more than 50 percent of the “area median income” (AMI).

While well-meaning, these bills would impose new obstacles in the planning and development of affordable housing, limiting the City’s ability to construct the housing and in effect reducing the number of new affordable units available to New Yorkers. These bills will hamper the incoming administration’s ability to reach its target of 200,000 new affordable housing units.

Table 1. Estimated impacts and FPI recommendations on City Council bills

| Bill | Impact on Affordability | FPI Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Int 1433-2025: Sets minimum percentage of new affordable rental units must be 2- and 3-bedroom units | Will decrease the number of supportive housing units by approximately 15%; Requires larger apartments than low-income households need, according to data. | Reject |

| Int 1437-2025: Sets maximum share of studio apartments in affordable units for older adults | Increases per-unit construction costs by 15%; Reduces number of new units for low-income seniors by 13%. | Reject |

| Int 1443-2025: Sets minimum percentage of rental units that must be affordable for extremely- and very-low-income households | Expected large cuts to federal funding will either make this unachievable, or drive up the cost, reducing housing for moderate-income households. | Reject |

Because resources for building new affordable housing units are limited—particularly in light of the Trump administration’s funding cuts to social services—policymakers must ensure that every penny goes towards maximizing the number of people and families who have access to rent-stabilized, reasonably priced, safe, high-quality housing. Each of these three bills significantly increases the cost of building a unit of affordable housing, as will be discussed in depth below, and thus threatens to reduce the overall amount of affordable housing available to New Yorkers who are already greatly in need.

The Council plans to vote on the bills before the end of 2025—likely this week—giving very little time for civic groups and planners to weigh in on the potential cost of the bills. As Crain’s reported, the Council appears motivated to pass the bills by year’s end because of the affordable-housing-related ballot measures that passed earlier this month, which changed the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP ) process so that council members have less ability to negotiate demands on developments in their districts. In light of the Council’s waning power, the bills can be seen as an assertion of control over future projects—using legislation in place of the individual negotiating power that voters just overturned.

Int. 1433: “Citywide percentage of rental units in projects receiving city financial assistance that must be 2- and 3-bedroom units.”

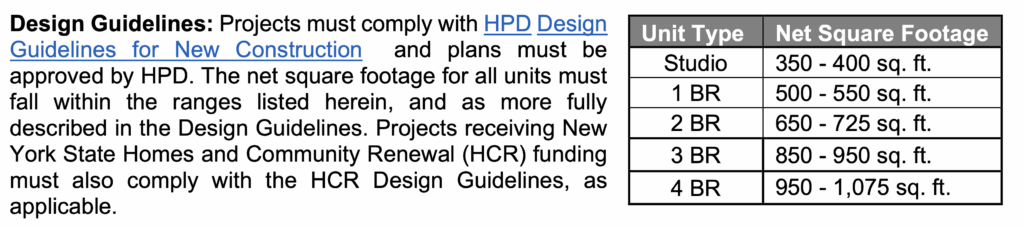

The HPD term sheet for new construction already requires that 30 percent of units in any given building be two- or three-bedrooms. Increasing this percentage further will likely mean that we build too many large units when demand for large units is relatively low. According to HPD, 81 percent of profiles on Housing Connect, its portal for finding affordable housing, are for households of just one or two people, and just 19 percent are for households of three or more people. While the demand reflected in Housing Connect may underestimate the true demand, it is also the case that, of households earning less than the median income in the city, 72 percent have just one or two people. These datapoints suggest that the primary demand for low-income housing comes from households who only need a single bedroom.

Exhibit A. HPD term sheet for New Construction Finance, Design and Construction Requirements

For special needs and supportive housing this bill has particularly damaging consequences. Almost all the need for supportive housing comes from households of just one or two people. That means that we can maximize the number of people served by building studios and one-bedrooms for this population. Legislating a minimum number of two- and three-bedrooms will dramatically reduce the number of overall units that can be produced to support vulnerable populations in need of services and supportive housing. For these types of buildings, mandating a minimum of 30 percent of units to be two or more bedrooms would reduce the overall number of units by about 15 percent. In other words, for every one hundred supportive housing units that can currently be constructed, this new legislation would result in only 85 supportive housing units being built given the same space and resources.

Legislating a minimum number of family sized units will create new bureaucratic barriers to producing new housing—an issue the City is working hard to address. Additionally, building larger apartments comes at a higher cost per unit (simply due to larger size). With an incoming mayoral administration that has the goal of building 200,000 new affordable apartments, this legislation will dramatically increase the price tag of completing that unit-based goal.

Int. 1437: “Maximum citywide percentage of studio apartments in city-funded projects to construct rental units for older adults.”

Even more than the preceding bill, this proposed legislation—which sets a maximum amount of affordable housing for older adults that can be built as studio apartments—has little merit in a market desperate for new units. By capping the number of studio apartments in City-funded housing for older adults, this proposal functionally reduces the number of rent-stabilized, affordable apartments that the City will be able to offer low-income older adults.

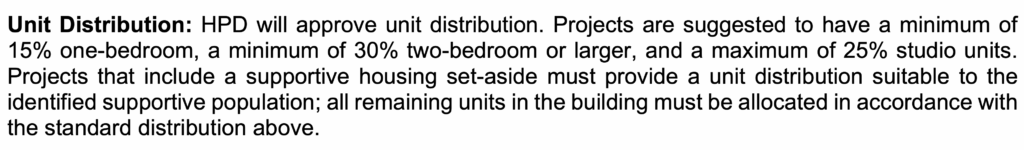

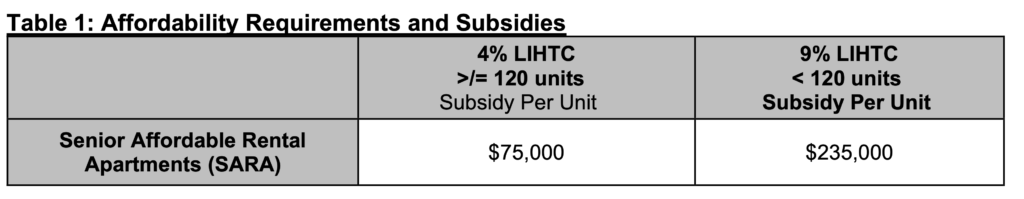

The Senior Affordable Rental Apartments (SARA) program subsidizes the development of affordable apartments for low-income older adults in New York City. As shown in Exhibit A—images from the HPD term sheet for SARA projects—these subsidies are currently set at a fixed amount no matter the size of the unit. That means that the subsidy available to build an apartment under the SARA program is fixed no matter the size of the units. But larger apartments are clearly more expensive to build, thus affordable developers will be required to raise additional funds from elsewhere to make a building financially viable, or be forced to drop the project all together.

Say, for example, that it costs $300 per square foot to build a new residential building in New York City. An affordable housing project will need about $105,000 to build a studio apartment, $150,000 to build a one-bedroom, and $195,000 to build a two-bedroom. Building a one-bedroom apartment is nearly 50 percent more expensive than building a studio apartment. A new SARA project that is planned to be ten floors on a 10,000-square-foot plot of land could accommodate nearly two hundred fifty studio apartments but only two hundred one-bedrooms. That’s a loss of fifty affordable housing units that are of great need in the City.

What’s more, assuming the financing of SARA projects stays the same, forcing more one- and two- bedrooms will reduce the City’s subsidy per square foot of space. This is a problem because it means projects will need to raise scarce resources from elsewhere and may need to limit the affordability levels they can offer to residents. Overall, FPI estimates that this legislation will raise the cost per unit of affordable housing by about 15 percent. These heightened costs will reduce construction and affordability of new apartments.

Exhibit B. Current design requirements and subsidy amounts under HPD’s SARA program

As with all of these bills, we face the deeply uncomfortable reality that we must make every dollar count to maximize the number of affordable units we can supply to New Yorkers. For any given amount of funding for new affordable housing development, mandating minimum apartment sizes puts a rigid limit on the amount one can build with each dollar. Imposing this new standard will have severe consequences for the quantity of affordable housing units the City can offer older adults, many of whom live on fixed income and are in severe need of sustainable housing solutions. While studio apartments may not be the ideal living situation, the City must use them as a tool to meet its production goals for affordable housing.

Int. 1443: “Citywide percentage of rental units in projects receiving city financial assistance that must be affordable for extremely low-income and very low-income households.”

The third bill would require that at least 50 percent of newly built or preserved units receiving financing or subsidy from the City (other than funding that is allocated “as-of-right”, such as 421-a or 485-x) be allocated towards “extremely low” (0%–30% AMI) or “very low” (31%–50% AMI) income households. The bill would create new obstacles for HPD and slow the planning process for building new affordable housing, threatening the Mamdani housing agenda. What’s more, HPD is already meeting these targets.

Data on 2014–2025 HPD projects shows that about 50% of rental units produced and preserved by HPD through programs other than 421-a are considered “deeply affordable” apartments (affordable to households making less than 50% of the area median income). This is particularly true in the 2020–2025 period, during which more than 50% of new or preserved income restricted rental apartments were “deeply affordable.” In contrast, the 421-a program produces many more units overall, but only about a third are income-restricted and rent-stabilized. Of those income-restricted units, the vast majority are targeted at households making between 121–165% of the area median income (well above the city’s median income).

The bill’s most concerning aspect is the timing. It is widely expected that federal Section 8 funds, which support many deeply affordable units in New York, will soon be cut by the Trump administration. event With the loss of this guaranteed rental income, the viability of building deeply affordable housing becomes much more tenuous and New York City will need to find new sources of financing to keep building deeply affordable units at the rate it currently maintains. Locking in a fixed rate of deeply affordable development at this time could result in limiting the amount of middle-income housing that gets developed, since the City may need to offset higher costs of developing deeply affordable units with market-rate development. Since the City is greatly in need of housing for middle-class families, this would be a major setback in achieving a robust affordability agenda.

Table 2. 100% affordable rental units by income-level for HPD new construction and preservation

| 0%–30% AMI |

31%–50% AMI

|

51–80% AMI

|

81–120% AMI

|

121–165% AMI

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014–2025 (Units) | 46,416 | 37,706 | 73,853 | 11,751 | 15,838 |

| 2014–2025 (% of units) | 31% | 25% | 49% | 8% | 11% |

| 2020–2025 (units) | 24,598 | 16,453 | 26,548 | 5,309 | 8,742 |

| 2020–2025 (% of units) | 30% | 17% | 28% | 6% | 9% |

Table 3. 100% affordable rental units by income-level for HPD new construction only

|

51–80% AMI

|

81–120% AMI

|

121–165% AMI

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014–2025 (Units) | 23,360 | 11,084 | 26,698 | 3,821 | 9,648 |

| 2014–2025 (% of units) | 31% | 15% | 35% | 5% | 13% |

| 2020–2025 (Units) | 13,192 | 5,896 | 10,217 | 1,545 | 7,895 |

| 2020–2025 (% of units) | 34% | 15% | 26% | 4% | 20% |

Table 4. Mixed-income rental units by income level for HPD new construction and preservation

|

0%–30% AMI

|

31%–50% AMI

|

51–80% AMI

|

81–120% AMI

|

121–165% AMI | All income restricted units | Total Units (including market rate) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014–2025 (Units) | 778 | 3,744 | 13,495 | 3,433 | 22,524 | 44,010 | 149,940 |

| 2014–2025 (Units) | 1% | 2% | 9% | 9% | 15% | 29% | |

| 2014–2025 (Units) | 364 | 2,182 | 5,784 | 1,517 | 17,455 | 27,310 | 94,996 |

| 2020–2025 (% of units) | 0% | 2% | 6% | 2% | 18% | 29% |

Conclusion

In sum, the Council bills being deliberated this week will severely limit the ability for the new mayoral administration to achieve its affordable housing goals. The bills are well-intentioned but poorly designed to effectively address the needs of city renters. Particularly in the context of federal cuts to housing vouchers and other public service funding, these bills heighten costs and limit affordability at a time when maximizing affordability for households of all income levels is imperative. The Council should reject these bills and instead find a way to work with the new administration on their shared affordable housing goals.

City Council’s Housing Bills Would Make Housing Less Affordable

December 11, 2025 |

Executive Summary

- The City Council will likely vote next week on a series of “term sheet bills” that would legislate new rigid restrictions on city-financed affordable housing development and preservation.

- Int 1433-2025: A bill that requires all housing projects receiving public subsidy from the City to contain a minimum share of two- and three-bedroom apartments;

- Int 1437-2025: A bill that would cap the number of studio apartments in city-subsidized senior housing; and

- Int 1443-2025: A bill that would require that half of all income-restricted units in city-subsidized housing be targeted at households making no more than 50 percent of the “area median income” (AMI).

- These bills, though well-intentioned, will drive up the cost of developing new affordable housing in the city and put major obstacles in the way of the incoming Mayor’s affordable housing agenda.

- The bills will significantly reduce the number of overall affordable units that the City can develop by driving up costs and making the housing development pipeline more complex.

- Particularly in the context of cuts to federal Section 8 funding, these bills will limit the capacity of New York City to develop housing that is affordable for low- and middle-income families

This week, City Council will consider a series of bills that would put major new constraints on city-financed affordable housing. The bills are:

• Int 1433-2025: A bill that requires all housing projects receiving public subsidy from the City to contain a minimum share of two- and three-bedroom apartments;

• Int 1437-2025: A bill that would cap the number of studio apartments in City-subsidized senior housing; and

• Int 1443-2025: A bill that would require that half of all income-restricted units in city-subsidized housing be targeted at households making no more than 50 percent of the “area median income” (AMI).

While well-meaning, these bills would impose new obstacles in the planning and development of affordable housing, limiting the City’s ability to construct the housing and in effect reducing the number of new affordable units available to New Yorkers. These bills will hamper the incoming administration’s ability to reach its target of 200,000 new affordable housing units.

Table 1. Estimated impacts and FPI recommendations on City Council bills

| Bill | Impact on Affordability | FPI Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Int 1433-2025: Sets minimum percentage of new affordable rental units must be 2- and 3-bedroom units | Will decrease the number of supportive housing units by approximately 15%; Requires larger apartments than low-income households need, according to data. | Reject |

| Int 1437-2025: Sets maximum share of studio apartments in affordable units for older adults | Increases per-unit construction costs by 15%; Reduces number of new units for low-income seniors by 13%. | Reject |

| Int 1443-2025: Sets minimum percentage of rental units that must be affordable for extremely- and very-low-income households | Expected large cuts to federal funding will either make this unachievable, or drive up the cost, reducing housing for moderate-income households. | Reject |

Because resources for building new affordable housing units are limited—particularly in light of the Trump administration’s funding cuts to social services—policymakers must ensure that every penny goes towards maximizing the number of people and families who have access to rent-stabilized, reasonably priced, safe, high-quality housing. Each of these three bills significantly increases the cost of building a unit of affordable housing, as will be discussed in depth below, and thus threatens to reduce the overall amount of affordable housing available to New Yorkers who are already greatly in need.

The Council plans to vote on the bills before the end of 2025—likely this week—giving very little time for civic groups and planners to weigh in on the potential cost of the bills. As Crain’s reported, the Council appears motivated to pass the bills by year’s end because of the affordable-housing-related ballot measures that passed earlier this month, which changed the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP ) process so that council members have less ability to negotiate demands on developments in their districts. In light of the Council’s waning power, the bills can be seen as an assertion of control over future projects—using legislation in place of the individual negotiating power that voters just overturned.

Int. 1433: “Citywide percentage of rental units in projects receiving city financial assistance that must be 2- and 3-bedroom units.”

The HPD term sheet for new construction already requires that 30 percent of units in any given building be two- or three-bedrooms. Increasing this percentage further will likely mean that we build too many large units when demand for large units is relatively low. According to HPD, 81 percent of profiles on Housing Connect, its portal for finding affordable housing, are for households of just one or two people, and just 19 percent are for households of three or more people. While the demand reflected in Housing Connect may underestimate the true demand, it is also the case that, of households earning less than the median income in the city, 72 percent have just one or two people. These datapoints suggest that the primary demand for low-income housing comes from households who only need a single bedroom.

Exhibit A. HPD term sheet for New Construction Finance, Design and Construction Requirements

For special needs and supportive housing this bill has particularly damaging consequences. Almost all the need for supportive housing comes from households of just one or two people. That means that we can maximize the number of people served by building studios and one-bedrooms for this population. Legislating a minimum number of two- and three-bedrooms will dramatically reduce the number of overall units that can be produced to support vulnerable populations in need of services and supportive housing. For these types of buildings, mandating a minimum of 30 percent of units to be two or more bedrooms would reduce the overall number of units by about 15 percent. In other words, for every one hundred supportive housing units that can currently be constructed, this new legislation would result in only 85 supportive housing units being built given the same space and resources.

Legislating a minimum number of family sized units will create new bureaucratic barriers to producing new housing—an issue the City is working hard to address. Additionally, building larger apartments comes at a higher cost per unit (simply due to larger size). With an incoming mayoral administration that has the goal of building 200,000 new affordable apartments, this legislation will dramatically increase the price tag of completing that unit-based goal.

Int. 1437: “Maximum citywide percentage of studio apartments in city-funded projects to construct rental units for older adults.”

Even more than the preceding bill, this proposed legislation—which sets a maximum amount of affordable housing for older adults that can be built as studio apartments—has little merit in a market desperate for new units. By capping the number of studio apartments in City-funded housing for older adults, this proposal functionally reduces the number of rent-stabilized, affordable apartments that the City will be able to offer low-income older adults.

The Senior Affordable Rental Apartments (SARA) program subsidizes the development of affordable apartments for low-income older adults in New York City. As shown in Exhibit A—images from the HPD term sheet for SARA projects—these subsidies are currently set at a fixed amount no matter the size of the unit. That means that the subsidy available to build an apartment under the SARA program is fixed no matter the size of the units. But larger apartments are clearly more expensive to build, thus affordable developers will be required to raise additional funds from elsewhere to make a building financially viable, or be forced to drop the project all together.

Say, for example, that it costs $300 per square foot to build a new residential building in New York City. An affordable housing project will need about $105,000 to build a studio apartment, $150,000 to build a one-bedroom, and $195,000 to build a two-bedroom. Building a one-bedroom apartment is nearly 50 percent more expensive than building a studio apartment. A new SARA project that is planned to be ten floors on a 10,000-square-foot plot of land could accommodate nearly two hundred fifty studio apartments but only two hundred one-bedrooms. That’s a loss of fifty affordable housing units that are of great need in the City.

What’s more, assuming the financing of SARA projects stays the same, forcing more one- and two- bedrooms will reduce the City’s subsidy per square foot of space. This is a problem because it means projects will need to raise scarce resources from elsewhere and may need to limit the affordability levels they can offer to residents. Overall, FPI estimates that this legislation will raise the cost per unit of affordable housing by about 15 percent. These heightened costs will reduce construction and affordability of new apartments.

Exhibit B. Current design requirements and subsidy amounts under HPD’s SARA program

As with all of these bills, we face the deeply uncomfortable reality that we must make every dollar count to maximize the number of affordable units we can supply to New Yorkers. For any given amount of funding for new affordable housing development, mandating minimum apartment sizes puts a rigid limit on the amount one can build with each dollar. Imposing this new standard will have severe consequences for the quantity of affordable housing units the City can offer older adults, many of whom live on fixed income and are in severe need of sustainable housing solutions. While studio apartments may not be the ideal living situation, the City must use them as a tool to meet its production goals for affordable housing.

Int. 1443: “Citywide percentage of rental units in projects receiving city financial assistance that must be affordable for extremely low-income and very low-income households.”

The third bill would require that at least 50 percent of newly built or preserved units receiving financing or subsidy from the City (other than funding that is allocated “as-of-right”, such as 421-a or 485-x) be allocated towards “extremely low” (0%–30% AMI) or “very low” (31%–50% AMI) income households. The bill would create new obstacles for HPD and slow the planning process for building new affordable housing, threatening the Mamdani housing agenda. What’s more, HPD is already meeting these targets.

Data on 2014–2025 HPD projects shows that about 50% of rental units produced and preserved by HPD through programs other than 421-a are considered “deeply affordable” apartments (affordable to households making less than 50% of the area median income). This is particularly true in the 2020–2025 period, during which more than 50% of new or preserved income restricted rental apartments were “deeply affordable.” In contrast, the 421-a program produces many more units overall, but only about a third are income-restricted and rent-stabilized. Of those income-restricted units, the vast majority are targeted at households making between 121–165% of the area median income (well above the city’s median income).

The bill’s most concerning aspect is the timing. It is widely expected that federal Section 8 funds, which support many deeply affordable units in New York, will soon be cut by the Trump administration. event With the loss of this guaranteed rental income, the viability of building deeply affordable housing becomes much more tenuous and New York City will need to find new sources of financing to keep building deeply affordable units at the rate it currently maintains. Locking in a fixed rate of deeply affordable development at this time could result in limiting the amount of middle-income housing that gets developed, since the City may need to offset higher costs of developing deeply affordable units with market-rate development. Since the City is greatly in need of housing for middle-class families, this would be a major setback in achieving a robust affordability agenda.

Table 2. 100% affordable rental units by income-level for HPD new construction and preservation

| 0%–30% AMI |

31%–50% AMI

|

51–80% AMI

|

81–120% AMI

|

121–165% AMI

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014–2025 (Units) | 46,416 | 37,706 | 73,853 | 11,751 | 15,838 |

| 2014–2025 (% of units) | 31% | 25% | 49% | 8% | 11% |

| 2020–2025 (units) | 24,598 | 16,453 | 26,548 | 5,309 | 8,742 |

| 2020–2025 (% of units) | 30% | 17% | 28% | 6% | 9% |

Table 3. 100% affordable rental units by income-level for HPD new construction only

|

51–80% AMI

|

81–120% AMI

|

121–165% AMI

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014–2025 (Units) | 23,360 | 11,084 | 26,698 | 3,821 | 9,648 |

| 2014–2025 (% of units) | 31% | 15% | 35% | 5% | 13% |

| 2020–2025 (Units) | 13,192 | 5,896 | 10,217 | 1,545 | 7,895 |

| 2020–2025 (% of units) | 34% | 15% | 26% | 4% | 20% |

Table 4. Mixed-income rental units by income level for HPD new construction and preservation

|

0%–30% AMI

|

31%–50% AMI

|

51–80% AMI

|

81–120% AMI

|

121–165% AMI | All income restricted units | Total Units (including market rate) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014–2025 (Units) | 778 | 3,744 | 13,495 | 3,433 | 22,524 | 44,010 | 149,940 |

| 2014–2025 (Units) | 1% | 2% | 9% | 9% | 15% | 29% | |

| 2014–2025 (Units) | 364 | 2,182 | 5,784 | 1,517 | 17,455 | 27,310 | 94,996 |

| 2020–2025 (% of units) | 0% | 2% | 6% | 2% | 18% | 29% |

Conclusion

In sum, the Council bills being deliberated this week will severely limit the ability for the new mayoral administration to achieve its affordable housing goals. The bills are well-intentioned but poorly designed to effectively address the needs of city renters. Particularly in the context of federal cuts to housing vouchers and other public service funding, these bills heighten costs and limit affordability at a time when maximizing affordability for households of all income levels is imperative. The Council should reject these bills and instead find a way to work with the new administration on their shared affordable housing goals.