Does New York State Have Universal Pre-K?

January 10, 2025 |

First introduced in 1997, the State’s universal Pre-K program remains short of universal

This year, New York State plans to spend $1.2 billion on pre-kindergarten programs for three- and four-year-olds across the state. This funding is supposed to establish universal pre-kindergarten (UPK) for every four-year-old in the state. The program’s actual reach falls short of its stated goals, supporting just over half of four-year-olds outside New York City and other major cities. More recently, the state’s largest cities have expanded UPK to three-year-olds. Nearly no three-year-olds outside these cities are supported by UPK. Further, the program’s widespread provision of half-day seats, rather than full day seats, shortchanges working parents.

In recent years, the State has substantially increased funding to the nearly 30-year old UPK program. Nevertheless, its funding structure makes inadequate grants to many districts, limiting their incentive or ability to start pre-kindergarten programs. Further, outside New York City, districts’ administrative and fiscal constraints and reliance on contracted providers limit the use of UPK programs even in districts where seats are available.

This brief will first provide an overview of UPK’s reach in New York State, before describing the program’s funding structure and history. Finally, the brief will describe the challenges facing New York’s UPK program.

UPK in New York: Still short of universal

By the State’s account, it currently provides enough UPK funding to provide a UPK seat to every four-year-old in the State. Nevertheless, the program remains far short of universal, with incomplete coverage of four-year-olds outside of the state’s major cities and limited provision for three-year-olds across the state.

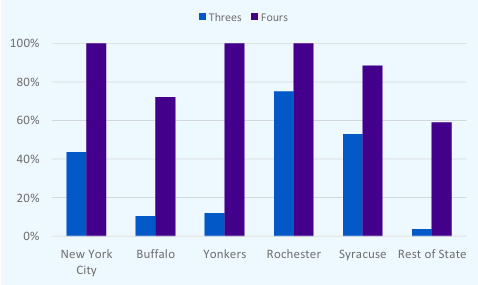

The state’s “big five” school districts – New York City, Buffalo, Yonkers, Rochester, and Syracuse – offer stronger UPK programs than those in the rest of the state. Under the State education law, the big five districts operate as city agencies funded by the cities’ general funds, not the dedicated school taxes common in the rest of the state. These districts have been better positioned to roll out UPK programs.

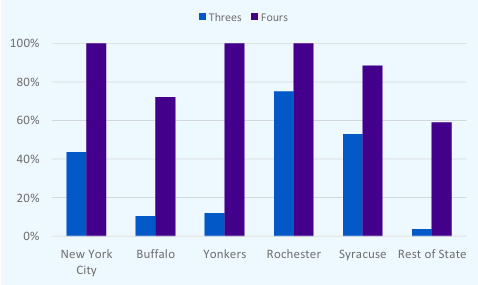

New York City’s UPK program offers seats for all four-year-olds and has made recent progress toward providing seats for all three-year-olds. Two of the other big five districts, Yonkers and Rochester, also provide seats to all four-year-olds, while Buffalo and Syracuse provide seats to over 70 percent of four-year-olds as of school year 2023 (the most recent data available).[1]

Districts outside the City remain far short of providing universal pre-K. In school year 2020, 43 percent of four-year-olds in districts other than New York City were enrolled in UPK; increased funding in recent years has pushed this level to 59 percent in school year 2023 (according to State benchmarks for full coverage).

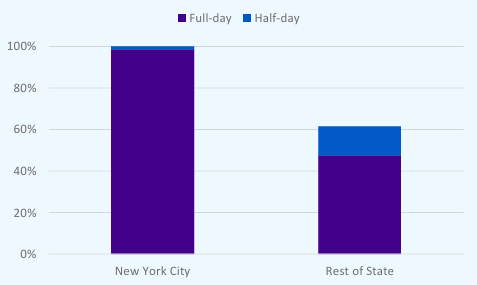

Figure 1. Share of three- and four-year-olds enrolled in UPK by region, school year 2023

The State’s enrollment benchmark for universal coverage in each district is set at 85 percent of that district’s kindergarten enrollment. While kindergarten enrollment reflects all of a district’s five-year-olds, pre-kindergarten enrollment is not mandatory, and the State does not expect 100 percent uptake.

This method for setting universal coverage benchmarks, however, which is established in State law, does not guarantee that enrollment targets closely align with the actual numbers of three- and four-year-olds in a district. In New York City, for instance, Census data estimates that the number of three- and four-year-olds was about 20 percent higher than the number of five-year-olds in 2022.[2] As a result, the City’s UPK program only enrolled 63 percent of four-year-olds (based on the Census estimate) in school year 2023, despite meeting the State benchmark for enrolling 85 percent of kindergarteners. Because the City offers seats to all UPK applicants, this does not necessarily reflect a funding shortfall. Rather, it may indicate that all children apply, a result of incomplete outreach, and that not all offers are accepted, often because programs are too far from applicants’ homes.

Outside the City, 48 percent of four-year-olds were enrolled in UPK, according to Census estimates. Four-year-old UPK is especially limited in the Capital District and the Hudson Valley. Districts in these regions are generally wealthier, and therefore receive lower per-pupil UPK allocations, which will be discussed below. However, many of these districts lack the resources to fund UPK programs locally. Unlike New York City, local revenue in the rest of the state is constrained by a property tax cap, which restricts the annual growth in local property tax levies. This limits districts’ ability to fund UPK programs with local resources.

In recent years, major cities have expanded UPK to three-year-olds. While New York City has made progress extending UPK to three-year-olds (which the City calls 3K), its enrollment remains below full enrollment, and programs in other districts are extremely limited. In school year 2023, New York City’s 3K program enrolled 27,600 pupils – nearly 60 percent fewer than the 64,000 four-year-olds enrolled in UPK. This enrollment level is just 44 percent of the State’s benchmark for full coverage, but just 29 percent of the City’s three-year-olds, according to Census estimates.[3] Nevertheless, 3K enrollment has been rising steadily in recent years and the City claims to provide enough 3K seats to all families that want one. This progress may be threatened by recent budget cuts, which have created operational challenges, and many families report being initially denied a seat or offered one far from their home, limiting uptake.[4]

Rochester and Syracuse have relatively strong three-year-old programs, meeting 75 percent and 53 percent, respectively, of the State’s benchmark full coverage. While Buffalo and Yonkers have three-year-old programs, their uptake has been limited, with each around 10 percent of the State benchmark.

Beyond these cities, coverage is extremely limited. Just 14 percent of districts offer UPK to three-year-olds. In school year 2023, these districts enrolled 3,300 pupils. This level is 6 percent of four-year-old UPK enrollment and reflects just 4 percent of the State’s enrollment benchmark.

How UPK funding works

State aid for UPK is currently allocated by two funding streams: a formula-based grant, called UPK, available to districts that have opted to create programs, and a competitive grant to facilitate the creation of new seats, called Statewide Universal Full-day Prekindergarten, or SUFPK. The State’s use of two funding streams is the result of the program’s funding history, which has grown in fits and starts. Historically, UPK provided continuing operating funding, while SUFPK provided grants for program expansions. Districts’ past SUFPK grants, however, are continuous, muddling the distinction between it and UPK over time.

The State’s UPK grants provide funding districts with funding per pupil enrolled in their UPK programs. Since school year 2007, districts’ per-pupil awards have been set at either half of a district’s foundation aid amount or a selected aid amount that factors in districts’ wealth and ranged between $2,700 and $4,000. Since school year 2022, this formula was doubled, meaning districts received at least $5,400 per new pupil. This per-pupil rate is then multiplied by the number of pupils enrolled in the prior year. Per-pupil funding has generally been set lower than foundation aid because districts’ use of contracted providers (discussed below) is less expensive than the use of public school teachers.

Over the past twenty years, however, the State has often created new UPK funding programs, at times allocating awards, which it refers to as SUFPK grants, on a discretionary basis or alternative formula. In 2019, SUFPK allocations were consolidated into districts’ primary UPK allocation. Since then, the State has appropriated further SUFPK funds to support the creation of new UPK seats. As such, districts’ per-pupil grant levels reflect both the State UPK formula at the time the district created its program and any SUFPK expansion grants made over the life of the program that have been consolidated into State UPK funding.

Districts’ per-pupil funding rates are frozen year-to-year, without an adjustment for inflation or any factor other than enrollment. This is unlike Foundation Aid, which funds public schools and is adjusted for inflation. Districts’ UPK allocations are reduced if enrollment falls from year-to-year. A district’s UPK allocation will be reduced by the district’s per-pupil funding rate times the decline in the enrollment.[5]

The fiscal year 2025 budget included a provision directing NYSED to study consolidating its UPK grant programs. NYSED’s report with findings and recommendations was due December 1, 2024, but has not been publically released as of the date of this report.

Because UPK grants have been allocated on a patchwork basis over decades, and not governed by a single consolidated formula, they are much less closely tied to districts’ resources and needs than Foundation Aid, the State’s primary school aid formula. Nevertheless, UPK funding structure provides moderately progressive per-pupil funding to districts across the state. The lowest wealth districts – those with the lowest property values – that host UPK programs are allocated $9,100 per pupil, 83 percent more than the $5,000 allocated to the highest wealth districts. As a result, districts in the lowest 10 percent by wealth provide more seats – 14,300 pupils – while districts in the highest 10 percent by wealth provide just 1,700 seats.

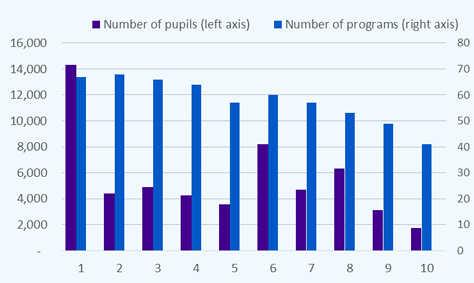

Figure 2. UPK allocations per pupil by district wealth decile, school year 2023

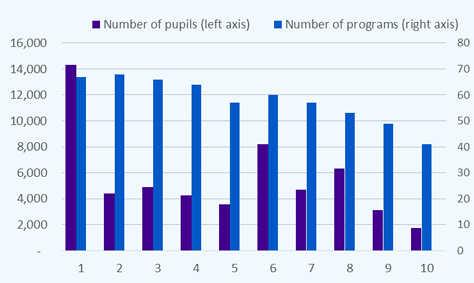

Figure 3. Number of UPK programs and pupils enrolled by district wealth decile, school year 2023

Note: New York City is excluded from this chart. It is in the 8th wealth decile. Its UPK program enrolls 91,000 pupils. Pupil counts converted to FTEs by weighting half-day seats at 0.5.

History

1990s: New York launches pre-kindergarten

New York’s pre-kindergarten program was enacted in 1997, making the state the second in the U.S. to establish a program aimed at offering publicly funded pre-kindergarten to four-year-olds.[6] The program, however, was not universal. School districts were given the option to establish pre-kindergarten programs, initially open only to four-year-olds.

Districts that opted to establish programs were provided pre-kindergarten allocations, phased in over four years. These initial allocations ranged between $2,700 and $4,000 per-pupil, determined by a formula that factored in districts’ wealth, measured by income and property values, and student need, measured by poverty rates, English language proficiency, and special education enrollment. As the program was phased in, districts were required to prioritize students with greater economic need.

In its first year, school year 1999, the State allocated $56.9 million to districts. While the State initially planned to spend $500 million annually on UPK by school year 2002, limited adoption by school districts restrained the program. Actual spending in school year 2002 was just $201.9 million, a level at which it would remain for the next five years. Just one-third of the State’s school districts participated in UPK.[7]

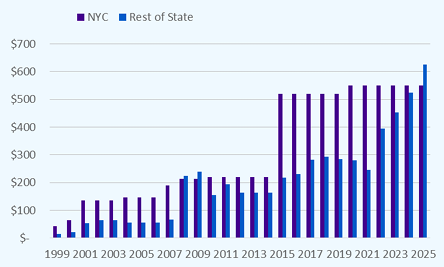

Early uptake in UPK was limited to the big five school districts and low-income suburbs, which received higher per-pupil grants. Three-quarters of the State’s initial UPK allocation ($42.4 million) went to New York City. As the State’s largest school district and early adopter of pre-kindergarten, New York City continued to receive more than half of State UPK funding until school year 2025. The City accounts for 40 percent of the state’s kindergarteners. Even in these large city districts, however, UPK programs were not actually universal. Grant levels were inadequate to offer seats to every four-year-old, leading districts to prioritize high-need students and neighborhoods.

Importantly, New York City has both the administrative and fiscal capacity to launch a new service, two features lacking in smaller districts. Unlike other districts, the city supplemented State funds with its own funding to create more expensive full-day seats in public schools. Other districts relied far more heavily on contracted seats, which were largely half-day early in the program.

2007: Campaign for Fiscal Equity

In 2007, concurrent with Campaign for Fiscal Equity (CFE)-led education reforms that established the Foundation Aid formula for school aid, the State committed an additional $146 million to UPK, adoption of which had been stagnant since 2002. The State reworked the UPK formula, granting districts half their Foundation aid per-pupil allocation or their prior-year UPK grant, whichever was larger. Grants were half of Foundation aid because UPK seats were still half-day and largely offered by contracted providers, which are less expensive than public schools.

By school year 2008, UPK funding had doubled to $437.9 million, and nearly two-thirds of school districts were participating in UPK.

This new funding push was short-lived. The 2008 recession and result fiscal crisis prompted the State to freeze UPK funding. No new districts were allowed to enter the program and its funding level remained consistent for the next six years. The districts left out of the program were generally relatively wealthy suburban districts, which stood to receive low UPK formula funding, had little spare fiscal capacity, and had no benefited from expansion grants that prioritized high-need districts.[8]

Districts that opted to establish programs were provided pre-kindergarten allocations, phased in over four years. These initial allocations ranged between $2,700 and $4,000 per-pupil, determined by a formula that factored in districts’ wealth, measured by income and property values, and student need, measured by poverty rates, English language proficiency, and special education enrollment. As the program was phased in, districts were required to prioritize students with greater economic need.

In its first year, school year 1999, the State allocated $56.9 million to districts. While the State initially planned to spend $500 million annually on UPK by school year 2002, limited adoption by school districts restrained the program. Actual spending in school year 2002 was just $201.9 million, a level at which it would remain for the next five years. Just one-third of the State’s school districts participated in UPK.[7]

Early uptake in UPK was limited to the big five school districts and low-income suburbs, which received higher per-pupil grants. Three-quarters of the State’s initial UPK allocation ($42.4 million) went to New York City. As the State’s largest school district and early adopter of pre-kindergarten, New York City continued to receive more than half of State UPK funding until school year 2025. The City accounts for 40 percent of the state’s kindergarteners. Even in these large city districts, however, UPK programs were not actually universal. Grant levels were inadequate to offer seats to every four-year-old, leading districts to prioritize high-need students and neighborhoods.

Importantly, New York City has both the administrative and fiscal capacity to launch a new service, two features lacking in smaller districts. Unlike other districts, the city supplemented State funds with its own funding to create more expensive full-day seats in public schools. Other districts relied far more heavily on contracted seats, which were largely half-day early in the program.

2014: New York City pursues a universal program

The next major investment in UPK came in 2014, when New York City launched a push to fully fund its UPK program and make the program truly universal. At the time, the program served only about one-third of eligible four-year-olds, with State grants (which had been frozen since 2007) inadequate to provide a seat to all four-year-olds.[9]

Following negotiations between the City and State, the State committed to allocating the City an additional $300 million in annual UPK funding from the State, while districts in the rest of the state received a collective $40 million. (The City had initially sought $340 million funded by higher local taxes on high-income earners. This was rejected, and as part of the deal with the State, the City was obligated to pay rent for charter schools, a $75 million annual cost).[10] The City’s UPK enrollment more than tripled, from 19,000 in 2013 to 68,000 in 2015, offering seats to all four-year-olds whose families applied.[11]

Separately, in 2017, the City launched its 3K program funded exclusively by city funds. The program launched initially in two of the city’s 32 school districts with a commitment from the Mayor to grow the program over time, particularly as state and federal funding became available.

Outside New York City, UPK expansion in the 2010s was limited. By school year 2021, 69 percent of districts in the State offered UPK programs—only slightly more than the 63 percent offering programs in 2013. Many non-urban districts that were created remained small: In 2021, just 43 percent of four-year-olds outside the city were enrolled in UPK, according to the State benchmark for full coverage.

2020s: Covid-era funding

The Covid pandemic brought a third wave of new investment to New York’s UPK program. Federal Covid relief legislation appropriated billions of dollars for public education systems nationwide. While New York directed most of this funding to K-12 education, finally fully phasing-in Foundation Aid, the State also made considerable investments in UPK. Because New York City’s 2014 allocation was sufficient to achieve universality in the city, State UPK funding increases since 2021 have all been directed to districts outside the City. Funds have been intended to pull in districts that have yet to establish programs and expand program with enrollment below the State’s benchmark for full coverage.

In fiscal year 2022, the State directed $210 million in federal funding to UPK.[12] The State appropriated an additional $125 million in State funds in fiscal year 2023 and $150 million in fiscal year 2024. Actual increases in UPK grants were smaller than these recent appropriations as enrollment in UPK programs outside New York City has remained below targets.

Of the fiscal year 2024 grants, $100 million was disbursed by a formula targeting districts with less-than-complete four-year-old UPK coverage and $50 million was awarded competitively by the State Education Department (SED). These expansion grants award districts $10,000 per pupil served by teachers holding the same certification required of public school teachers and $7,000 for non-certified teachers.[13] These per-pupil funding levels for new seats are higher than most districts’ existing per-pupil allocations. Higher funding is meant to draw in remaining districts without programs.

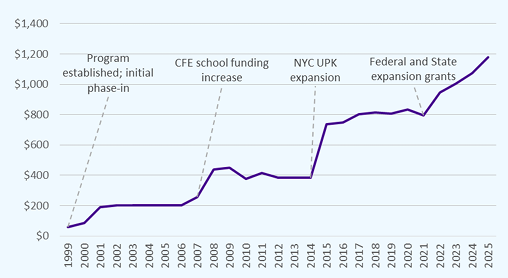

In fiscal year 2025, the State committed to taking over temporary federal UPK funding, bringing total annual State UPK allocations to $1.2 billion.

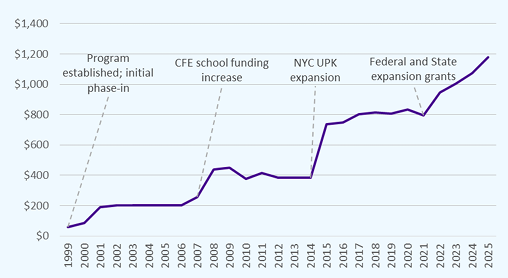

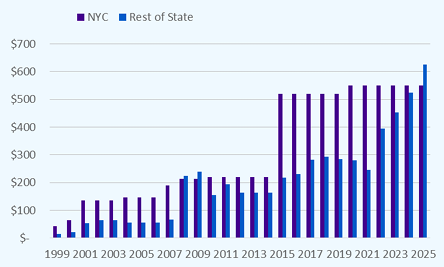

Figure 4. New York State UPK funding, school years 1999 to 2025

Figure 5. New York State UPK funding by region, school years 1999 to 2025

Challenges facing Statewide UPK

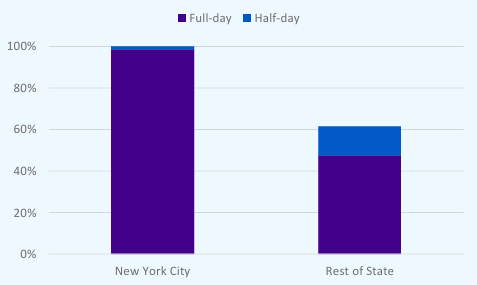

New York’s UPK system faces three further constraints: its high portion of seats offering only half-day education; a lack of centralized administration outside New York City; and per-pupil funding that is inadequate to support seats in public schools, especially in higher-cost districts.

Outside New York City, districts lag in providing full-day UPK instruction. In New York City, 99 percent of UPK seats provide full-day instruction, which follow the same hours as K-12 schools. While districts outside New York City have used recent years’ funding influx to improve, their UPK program provided full-day instruction to just 77 percent of pupils in school year 2023, up from 51 percent three years prior.

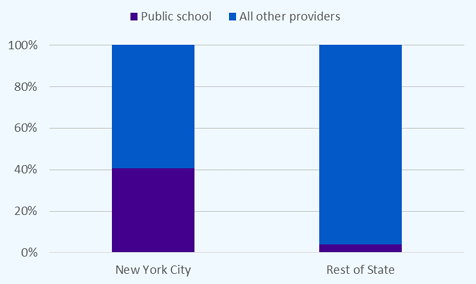

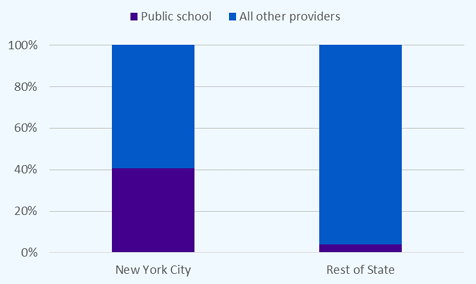

Figure 6. Full-day and half-day UPK as share of enrollment benchmarks, school year 2023

New York’s UPK program has always been designed to rely in part on independent providers, including daycare centers and non-public schools, to provide some UPK instruction. The State’s education law requires that districts use at least 10 percent of their UPK funding to contract seats from independent providers. In practice, reliance on these providers is far higher. In New York City, 59 percent of UPK seats are provided by non-school providers, while the City’s public schools provide the remaining seats.[14] Outside the City, by contrast, nearly all – 96 percent – of UPK seats are provided by independent providers. Of these independent providers, daycare centers and nonpublic schools provide more than three-quarters (79 percent) of seats. The remaining seats are provided by special education schools, Head Start programs, and BOCES, which provide vocational training.

UPK seats supported by independent providers are generally less expensive than those provided by public schools, which tend to pay higher wages. New York City funds its unusually high reliance on public schools by supplementing state funds with local funds. Other districts generally lack New York City’s fiscal capacity – larger cities have lower property values while non-urban districts have little ability to raise additional tax revenue.

Figure 7. UPK provider type by region, school year 2023

Outside major cities, UPK uptake is low even in districts with programs. This may be a function of these non-urban districts’ lack of central school district outreach and near-total reliance on independent providers. While districts manage UPK enrollment centrally, most users’ primary point of contact is with providers, not central school districts. As such, contracted providers often enroll pupils already enrolled at younger ages, shifting pupils from private pay to UPK’s per-pupil funding once they become eligible at age three or four. For families not already using contracted providers, awareness of UPK opportunities may be limited.

While more than half of New York City’s seats are provided outside its public schools, the City government’s greater capacity and the consolidation of its school district as a city agency afford a significant advantage in conducting outreach and enrolling new three- and four-year-olds. This feature of the rest of the State’s UPK programs, together with their limited ability to use local resources to fund programs is a significant barrier to the establishment of truly universal pre-kindergarten in New York State.

Sources

[1] School year 2023 refers to the school year beginning Fall 2022 and ending Spring 2023

[2] Census, ACS, 2022 1-year file

[3] ACS PUMS 1-year file

[4] https://ny1.com/nyc/all-boroughs/education/2024/05/21/nyc-3k-seats-

[5] https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/laws/EDN/3602-E

[6] https://www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/legacy/uploadedfiles/pcs_assets/2004-2006/pewpkndiversedeliveryjul2006pdf.pdf

[7] https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED573102.pdf

[8] https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED573102.pdf; https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED596299.pdf

[9] https://data.cityofnewyork.us/api/assets/E1F76BFB-2A67-468B-95E1-BACD15B5C488?02a_UPK.pdf

[10] https://ibo.nyc.ny.us/iboreports/savings-options-reducing-subsidies-december-2022.pdf

[11] https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/31/nyregion/de-blasio-universal-pre-k.html

[12] https://www.budget.ny.gov/pubs/archive/fy22/en/fy22en-fp.pdf

[13] https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/laws/EDN/3602-EE

[14] https://data.cityofnewyork.us/Education/Universal-Pre-K-UPK-School-Locations/kiyv-ks3f/about_data

Does New York State Have Universal Pre-K?

January 10, 2025 |

First introduced in 1997, the State’s universal Pre-K program remains short of universal

This year, New York State plans to spend $1.2 billion on pre-kindergarten programs for three- and four-year-olds across the state. This funding is supposed to establish universal pre-kindergarten (UPK) for every four-year-old in the state. The program’s actual reach falls short of its stated goals, supporting just over half of four-year-olds outside New York City and other major cities. More recently, the state’s largest cities have expanded UPK to three-year-olds. Nearly no three-year-olds outside these cities are supported by UPK. Further, the program’s widespread provision of half-day seats, rather than full day seats, shortchanges working parents.

In recent years, the State has substantially increased funding to the nearly 30-year old UPK program. Nevertheless, its funding structure makes inadequate grants to many districts, limiting their incentive or ability to start pre-kindergarten programs. Further, outside New York City, districts’ administrative and fiscal constraints and reliance on contracted providers limit the use of UPK programs even in districts where seats are available.

This brief will first provide an overview of UPK’s reach in New York State, before describing the program’s funding structure and history. Finally, the brief will describe the challenges facing New York’s UPK program.

UPK in New York: Still short of universal

By the State’s account, it currently provides enough UPK funding to provide a UPK seat to every four-year-old in the State. Nevertheless, the program remains far short of universal, with incomplete coverage of four-year-olds outside of the state’s major cities and limited provision for three-year-olds across the state.

The state’s “big five” school districts – New York City, Buffalo, Yonkers, Rochester, and Syracuse – offer stronger UPK programs than those in the rest of the state. Under the State education law, the big five districts operate as city agencies funded by the cities’ general funds, not the dedicated school taxes common in the rest of the state. These districts have been better positioned to roll out UPK programs.

New York City’s UPK program offers seats for all four-year-olds and has made recent progress toward providing seats for all three-year-olds. Two of the other big five districts, Yonkers and Rochester, also provide seats to all four-year-olds, while Buffalo and Syracuse provide seats to over 70 percent of four-year-olds as of school year 2023 (the most recent data available).[1]

Districts outside the City remain far short of providing universal pre-K. In school year 2020, 43 percent of four-year-olds in districts other than New York City were enrolled in UPK; increased funding in recent years has pushed this level to 59 percent in school year 2023 (according to State benchmarks for full coverage).

Figure 1. Share of three- and four-year-olds enrolled in UPK by region, school year 2023

The State’s enrollment benchmark for universal coverage in each district is set at 85 percent of that district’s kindergarten enrollment. While kindergarten enrollment reflects all of a district’s five-year-olds, pre-kindergarten enrollment is not mandatory, and the State does not expect 100 percent uptake.

This method for setting universal coverage benchmarks, however, which is established in State law, does not guarantee that enrollment targets closely align with the actual numbers of three- and four-year-olds in a district. In New York City, for instance, Census data estimates that the number of three- and four-year-olds was about 20 percent higher than the number of five-year-olds in 2022.[2] As a result, the City’s UPK program only enrolled 63 percent of four-year-olds (based on the Census estimate) in school year 2023, despite meeting the State benchmark for enrolling 85 percent of kindergarteners. Because the City offers seats to all UPK applicants, this does not necessarily reflect a funding shortfall. Rather, it may indicate that all children apply, a result of incomplete outreach, and that not all offers are accepted, often because programs are too far from applicants’ homes.

Outside the City, 48 percent of four-year-olds were enrolled in UPK, according to Census estimates. Four-year-old UPK is especially limited in the Capital District and the Hudson Valley. Districts in these regions are generally wealthier, and therefore receive lower per-pupil UPK allocations, which will be discussed below. However, many of these districts lack the resources to fund UPK programs locally. Unlike New York City, local revenue in the rest of the state is constrained by a property tax cap, which restricts the annual growth in local property tax levies. This limits districts’ ability to fund UPK programs with local resources.

In recent years, major cities have expanded UPK to three-year-olds. While New York City has made progress extending UPK to three-year-olds (which the City calls 3K), its enrollment remains below full enrollment, and programs in other districts are extremely limited. In school year 2023, New York City’s 3K program enrolled 27,600 pupils – nearly 60 percent fewer than the 64,000 four-year-olds enrolled in UPK. This enrollment level is just 44 percent of the State’s benchmark for full coverage, but just 29 percent of the City’s three-year-olds, according to Census estimates.[3] Nevertheless, 3K enrollment has been rising steadily in recent years and the City claims to provide enough 3K seats to all families that want one. This progress may be threatened by recent budget cuts, which have created operational challenges, and many families report being initially denied a seat or offered one far from their home, limiting uptake.[4]

Rochester and Syracuse have relatively strong three-year-old programs, meeting 75 percent and 53 percent, respectively, of the State’s benchmark full coverage. While Buffalo and Yonkers have three-year-old programs, their uptake has been limited, with each around 10 percent of the State benchmark.

Beyond these cities, coverage is extremely limited. Just 14 percent of districts offer UPK to three-year-olds. In school year 2023, these districts enrolled 3,300 pupils. This level is 6 percent of four-year-old UPK enrollment and reflects just 4 percent of the State’s enrollment benchmark.

How UPK funding works

State aid for UPK is currently allocated by two funding streams: a formula-based grant, called UPK, available to districts that have opted to create programs, and a competitive grant to facilitate the creation of new seats, called Statewide Universal Full-day Prekindergarten, or SUFPK. The State’s use of two funding streams is the result of the program’s funding history, which has grown in fits and starts. Historically, UPK provided continuing operating funding, while SUFPK provided grants for program expansions. Districts’ past SUFPK grants, however, are continuous, muddling the distinction between it and UPK over time.

The State’s UPK grants provide funding districts with funding per pupil enrolled in their UPK programs. Since school year 2007, districts’ per-pupil awards have been set at either half of a district’s foundation aid amount or a selected aid amount that factors in districts’ wealth and ranged between $2,700 and $4,000. Since school year 2022, this formula was doubled, meaning districts received at least $5,400 per new pupil. This per-pupil rate is then multiplied by the number of pupils enrolled in the prior year. Per-pupil funding has generally been set lower than foundation aid because districts’ use of contracted providers (discussed below) is less expensive than the use of public school teachers.

Over the past twenty years, however, the State has often created new UPK funding programs, at times allocating awards, which it refers to as SUFPK grants, on a discretionary basis or alternative formula. In 2019, SUFPK allocations were consolidated into districts’ primary UPK allocation. Since then, the State has appropriated further SUFPK funds to support the creation of new UPK seats. As such, districts’ per-pupil grant levels reflect both the State UPK formula at the time the district created its program and any SUFPK expansion grants made over the life of the program that have been consolidated into State UPK funding.

Districts’ per-pupil funding rates are frozen year-to-year, without an adjustment for inflation or any factor other than enrollment. This is unlike Foundation Aid, which funds public schools and is adjusted for inflation. Districts’ UPK allocations are reduced if enrollment falls from year-to-year. A district’s UPK allocation will be reduced by the district’s per-pupil funding rate times the decline in the enrollment.[5]

The fiscal year 2025 budget included a provision directing NYSED to study consolidating its UPK grant programs. NYSED’s report with findings and recommendations was due December 1, 2024, but has not been publically released as of the date of this report.

Because UPK grants have been allocated on a patchwork basis over decades, and not governed by a single consolidated formula, they are much less closely tied to districts’ resources and needs than Foundation Aid, the State’s primary school aid formula. Nevertheless, UPK funding structure provides moderately progressive per-pupil funding to districts across the state. The lowest wealth districts – those with the lowest property values – that host UPK programs are allocated $9,100 per pupil, 83 percent more than the $5,000 allocated to the highest wealth districts. As a result, districts in the lowest 10 percent by wealth provide more seats – 14,300 pupils – while districts in the highest 10 percent by wealth provide just 1,700 seats.

Figure 2. UPK allocations per pupil by district wealth decile, school year 2023

Figure 3. Number of UPK programs and pupils enrolled by district wealth decile, school year 2023

Note: New York City is excluded from this chart. It is in the 8th wealth decile. Its UPK program enrolls 91,000 pupils. Pupil counts converted to FTEs by weighting half-day seats at 0.5.

History

1990s: New York launches pre-kindergarten

New York’s pre-kindergarten program was enacted in 1997, making the state the second in the U.S. to establish a program aimed at offering publicly funded pre-kindergarten to four-year-olds.[6] The program, however, was not universal. School districts were given the option to establish pre-kindergarten programs, initially open only to four-year-olds.

Districts that opted to establish programs were provided pre-kindergarten allocations, phased in over four years. These initial allocations ranged between $2,700 and $4,000 per-pupil, determined by a formula that factored in districts’ wealth, measured by income and property values, and student need, measured by poverty rates, English language proficiency, and special education enrollment. As the program was phased in, districts were required to prioritize students with greater economic need.

In its first year, school year 1999, the State allocated $56.9 million to districts. While the State initially planned to spend $500 million annually on UPK by school year 2002, limited adoption by school districts restrained the program. Actual spending in school year 2002 was just $201.9 million, a level at which it would remain for the next five years. Just one-third of the State’s school districts participated in UPK.[7]

Early uptake in UPK was limited to the big five school districts and low-income suburbs, which received higher per-pupil grants. Three-quarters of the State’s initial UPK allocation ($42.4 million) went to New York City. As the State’s largest school district and early adopter of pre-kindergarten, New York City continued to receive more than half of State UPK funding until school year 2025. The City accounts for 40 percent of the state’s kindergarteners. Even in these large city districts, however, UPK programs were not actually universal. Grant levels were inadequate to offer seats to every four-year-old, leading districts to prioritize high-need students and neighborhoods.

Importantly, New York City has both the administrative and fiscal capacity to launch a new service, two features lacking in smaller districts. Unlike other districts, the city supplemented State funds with its own funding to create more expensive full-day seats in public schools. Other districts relied far more heavily on contracted seats, which were largely half-day early in the program.

2007: Campaign for Fiscal Equity

In 2007, concurrent with Campaign for Fiscal Equity (CFE)-led education reforms that established the Foundation Aid formula for school aid, the State committed an additional $146 million to UPK, adoption of which had been stagnant since 2002. The State reworked the UPK formula, granting districts half their Foundation aid per-pupil allocation or their prior-year UPK grant, whichever was larger. Grants were half of Foundation aid because UPK seats were still half-day and largely offered by contracted providers, which are less expensive than public schools.

By school year 2008, UPK funding had doubled to $437.9 million, and nearly two-thirds of school districts were participating in UPK.

This new funding push was short-lived. The 2008 recession and result fiscal crisis prompted the State to freeze UPK funding. No new districts were allowed to enter the program and its funding level remained consistent for the next six years. The districts left out of the program were generally relatively wealthy suburban districts, which stood to receive low UPK formula funding, had little spare fiscal capacity, and had no benefited from expansion grants that prioritized high-need districts.[8]

Districts that opted to establish programs were provided pre-kindergarten allocations, phased in over four years. These initial allocations ranged between $2,700 and $4,000 per-pupil, determined by a formula that factored in districts’ wealth, measured by income and property values, and student need, measured by poverty rates, English language proficiency, and special education enrollment. As the program was phased in, districts were required to prioritize students with greater economic need.

In its first year, school year 1999, the State allocated $56.9 million to districts. While the State initially planned to spend $500 million annually on UPK by school year 2002, limited adoption by school districts restrained the program. Actual spending in school year 2002 was just $201.9 million, a level at which it would remain for the next five years. Just one-third of the State’s school districts participated in UPK.[7]

Early uptake in UPK was limited to the big five school districts and low-income suburbs, which received higher per-pupil grants. Three-quarters of the State’s initial UPK allocation ($42.4 million) went to New York City. As the State’s largest school district and early adopter of pre-kindergarten, New York City continued to receive more than half of State UPK funding until school year 2025. The City accounts for 40 percent of the state’s kindergarteners. Even in these large city districts, however, UPK programs were not actually universal. Grant levels were inadequate to offer seats to every four-year-old, leading districts to prioritize high-need students and neighborhoods.

Importantly, New York City has both the administrative and fiscal capacity to launch a new service, two features lacking in smaller districts. Unlike other districts, the city supplemented State funds with its own funding to create more expensive full-day seats in public schools. Other districts relied far more heavily on contracted seats, which were largely half-day early in the program.

2014: New York City pursues a universal program

The next major investment in UPK came in 2014, when New York City launched a push to fully fund its UPK program and make the program truly universal. At the time, the program served only about one-third of eligible four-year-olds, with State grants (which had been frozen since 2007) inadequate to provide a seat to all four-year-olds.[9]

Following negotiations between the City and State, the State committed to allocating the City an additional $300 million in annual UPK funding from the State, while districts in the rest of the state received a collective $40 million. (The City had initially sought $340 million funded by higher local taxes on high-income earners. This was rejected, and as part of the deal with the State, the City was obligated to pay rent for charter schools, a $75 million annual cost).[10] The City’s UPK enrollment more than tripled, from 19,000 in 2013 to 68,000 in 2015, offering seats to all four-year-olds whose families applied.[11]

Separately, in 2017, the City launched its 3K program funded exclusively by city funds. The program launched initially in two of the city’s 32 school districts with a commitment from the Mayor to grow the program over time, particularly as state and federal funding became available.

Outside New York City, UPK expansion in the 2010s was limited. By school year 2021, 69 percent of districts in the State offered UPK programs—only slightly more than the 63 percent offering programs in 2013. Many non-urban districts that were created remained small: In 2021, just 43 percent of four-year-olds outside the city were enrolled in UPK, according to the State benchmark for full coverage.

2020s: Covid-era funding

The Covid pandemic brought a third wave of new investment to New York’s UPK program. Federal Covid relief legislation appropriated billions of dollars for public education systems nationwide. While New York directed most of this funding to K-12 education, finally fully phasing-in Foundation Aid, the State also made considerable investments in UPK. Because New York City’s 2014 allocation was sufficient to achieve universality in the city, State UPK funding increases since 2021 have all been directed to districts outside the City. Funds have been intended to pull in districts that have yet to establish programs and expand program with enrollment below the State’s benchmark for full coverage.

In fiscal year 2022, the State directed $210 million in federal funding to UPK.[12] The State appropriated an additional $125 million in State funds in fiscal year 2023 and $150 million in fiscal year 2024. Actual increases in UPK grants were smaller than these recent appropriations as enrollment in UPK programs outside New York City has remained below targets.

Of the fiscal year 2024 grants, $100 million was disbursed by a formula targeting districts with less-than-complete four-year-old UPK coverage and $50 million was awarded competitively by the State Education Department (SED). These expansion grants award districts $10,000 per pupil served by teachers holding the same certification required of public school teachers and $7,000 for non-certified teachers.[13] These per-pupil funding levels for new seats are higher than most districts’ existing per-pupil allocations. Higher funding is meant to draw in remaining districts without programs.

In fiscal year 2025, the State committed to taking over temporary federal UPK funding, bringing total annual State UPK allocations to $1.2 billion.

Figure 4. New York State UPK funding, school years 1999 to 2025

Figure 5. New York State UPK funding by region, school years 1999 to 2025

Challenges facing Statewide UPK

New York’s UPK system faces three further constraints: its high portion of seats offering only half-day education; a lack of centralized administration outside New York City; and per-pupil funding that is inadequate to support seats in public schools, especially in higher-cost districts.

Outside New York City, districts lag in providing full-day UPK instruction. In New York City, 99 percent of UPK seats provide full-day instruction, which follow the same hours as K-12 schools. While districts outside New York City have used recent years’ funding influx to improve, their UPK program provided full-day instruction to just 77 percent of pupils in school year 2023, up from 51 percent three years prior.

Figure 6. Full-day and half-day UPK as share of enrollment benchmarks, school year 2023

New York’s UPK program has always been designed to rely in part on independent providers, including daycare centers and non-public schools, to provide some UPK instruction. The State’s education law requires that districts use at least 10 percent of their UPK funding to contract seats from independent providers. In practice, reliance on these providers is far higher. In New York City, 59 percent of UPK seats are provided by non-school providers, while the City’s public schools provide the remaining seats.[14] Outside the City, by contrast, nearly all – 96 percent – of UPK seats are provided by independent providers. Of these independent providers, daycare centers and nonpublic schools provide more than three-quarters (79 percent) of seats. The remaining seats are provided by special education schools, Head Start programs, and BOCES, which provide vocational training.

UPK seats supported by independent providers are generally less expensive than those provided by public schools, which tend to pay higher wages. New York City funds its unusually high reliance on public schools by supplementing state funds with local funds. Other districts generally lack New York City’s fiscal capacity – larger cities have lower property values while non-urban districts have little ability to raise additional tax revenue.

Figure 7. UPK provider type by region, school year 2023

Outside major cities, UPK uptake is low even in districts with programs. This may be a function of these non-urban districts’ lack of central school district outreach and near-total reliance on independent providers. While districts manage UPK enrollment centrally, most users’ primary point of contact is with providers, not central school districts. As such, contracted providers often enroll pupils already enrolled at younger ages, shifting pupils from private pay to UPK’s per-pupil funding once they become eligible at age three or four. For families not already using contracted providers, awareness of UPK opportunities may be limited.

While more than half of New York City’s seats are provided outside its public schools, the City government’s greater capacity and the consolidation of its school district as a city agency afford a significant advantage in conducting outreach and enrolling new three- and four-year-olds. This feature of the rest of the State’s UPK programs, together with their limited ability to use local resources to fund programs is a significant barrier to the establishment of truly universal pre-kindergarten in New York State.

Sources

[1] School year 2023 refers to the school year beginning Fall 2022 and ending Spring 2023

[2] Census, ACS, 2022 1-year file

[3] ACS PUMS 1-year file

[4] https://ny1.com/nyc/all-boroughs/education/2024/05/21/nyc-3k-seats-

[5] https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/laws/EDN/3602-E

[6] https://www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/legacy/uploadedfiles/pcs_assets/2004-2006/pewpkndiversedeliveryjul2006pdf.pdf

[7] https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED573102.pdf

[8] https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED573102.pdf; https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED596299.pdf

[9] https://data.cityofnewyork.us/api/assets/E1F76BFB-2A67-468B-95E1-BACD15B5C488?02a_UPK.pdf

[10] https://ibo.nyc.ny.us/iboreports/savings-options-reducing-subsidies-december-2022.pdf

[11] https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/31/nyregion/de-blasio-universal-pre-k.html

[12] https://www.budget.ny.gov/pubs/archive/fy22/en/fy22en-fp.pdf

[13] https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/laws/EDN/3602-EE

[14] https://data.cityofnewyork.us/Education/Universal-Pre-K-UPK-School-Locations/kiyv-ks3f/about_data