How the CDPAP Transition Could Leave Thousands of Home Care Workers Uninsured

March 17, 2025 |

Key Findings

- New York State’s new home care fiscal intermediary plans to require workers in downstate areas to pay between $0.87 and $1.06 per hour to enroll in a health plan that doesn’t cover basic services like primary care and hospital visits.

- Workers statewide will have the option to pay over $200 per month to enroll in a plan with a $6,350 deductible that covers little before the deductible.

- Most disturbingly, these health insurance offers may cause workers to lose their existing health insurance. These offerings may mean that many workers who were previously eligible for coverage through the New York Essential Plan, a spouse’s plan, or an employer’s retirement plan will lose access to their existing coverage – which in virtually all cases would be far better than the coverage PPL is offering.

- PPL appears to be offering this weak coverage in order to avoid tax penalties it would otherwise owe under the Affordable Care Act.

- PPL’s health insurance offer may cause hundreds of thousands of workers to lose health insurance.

Introduction

The transition of New York’s Medicaid-funded Consumer-Directed Personal Assistance Program (CDPAP) to a single fiscal intermediary has been extremely controversial. The program, which provides home care to 280,000 elderly and disabled New Yorkers and employs as many as 400,000 workers,[1] is currently operated by around 600 fiscal intermediaries (FIs), who handle payroll and benefits for workers. Last year’s state budget mandated that the program be transitioned to a single, statewide FI by April 1, 2025, and this summer the state selected a Georgia-based company called Public Partnerships, LLC (PPL) as the new single FI.

The transition has been controversial, with proponents arguing that a single FI can administer the program more efficiently while opponents worry that consumers may lose benefits. The timeline of the transition has been doubly controversial: The state announced on March 10 that only 115,000 out of 280,000 consumers had “started or completed” the registration process with PPL, raising the possibility that thousands will not register in time for the April 1 deadline. Advocates continue to plead with the state to delay.

What has not become clear until very recently is that the transition may cause many workers to earn lower wages and lose access to health insurance. As I will discuss in this piece, PPL’s offer of coverage leaves workers much worse off than if PPL simply offered no health insurance at all; not only does it cover very little and cost workers a lot, but it will render them ineligible for the high-quality insurance many currently enjoy.

The PPL Healthcare Offer

PPL has been extremely vague about its plans for worker health insurance so far, saying only that workers downstate would be enrolled in its “PPL Minimum Essentials Coverage Preventive Plan (MEC Plan)” and that workers statewide would have the option to “a competitive benefits package that includes health insurance” with “benefits provided by Anthem.”[2] Since most current CDPAP FIs offer no health insurance at all, these offers sounded promising.

As workers have begun to receive further information, however, the details of PPL’s offer have become increasingly disturbing. Plan documents show that PPL’s health insurance offering is disturbingly bad.

PPL is offering two health insurance packages: A “Minimum Essential Coverage” package for downstate workers, with mandatory enrollment, and a “Minimum Value” plan for workers throughout the state, which workers can pay extra for. We will describe each in turn.

Plan 1: Minimum Essential Coverage

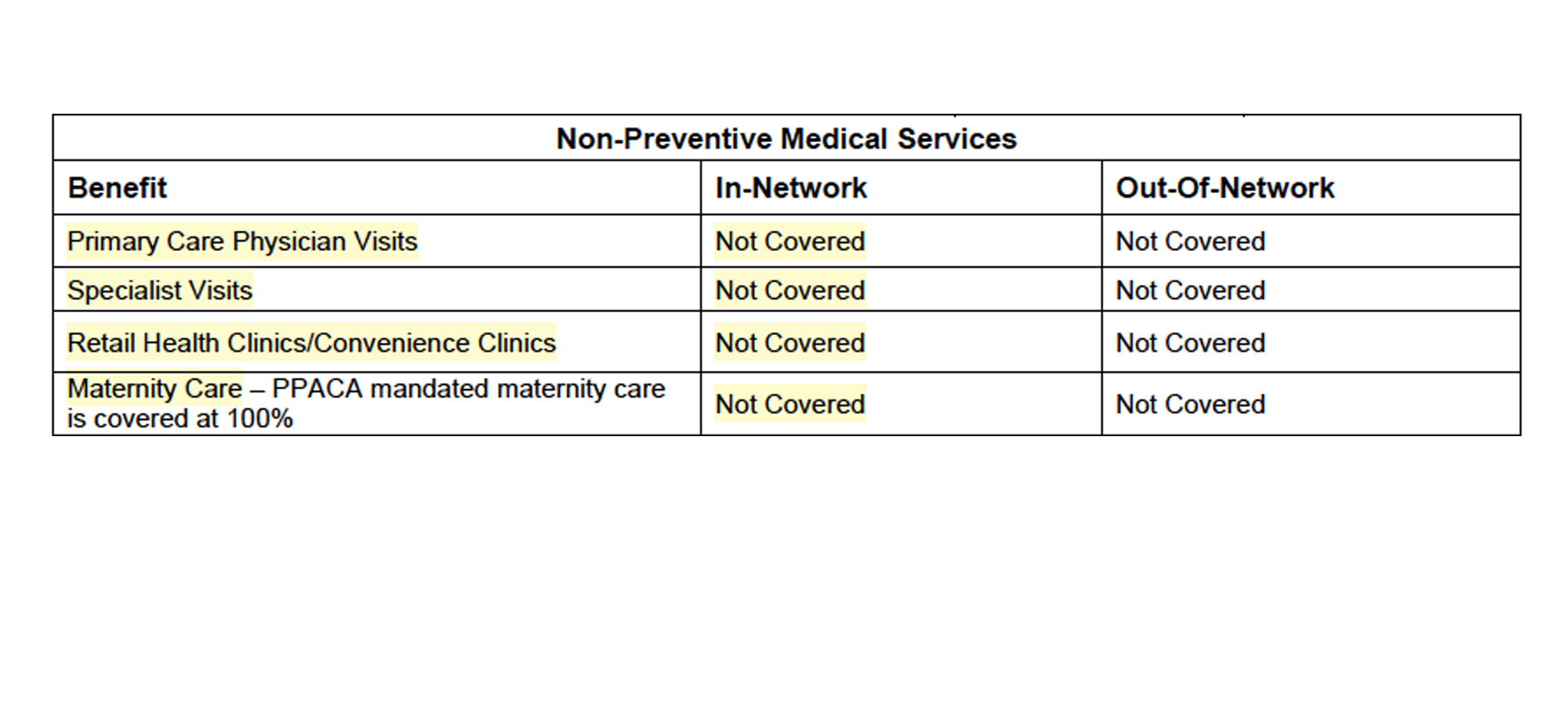

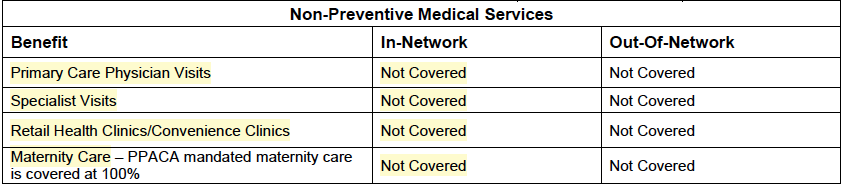

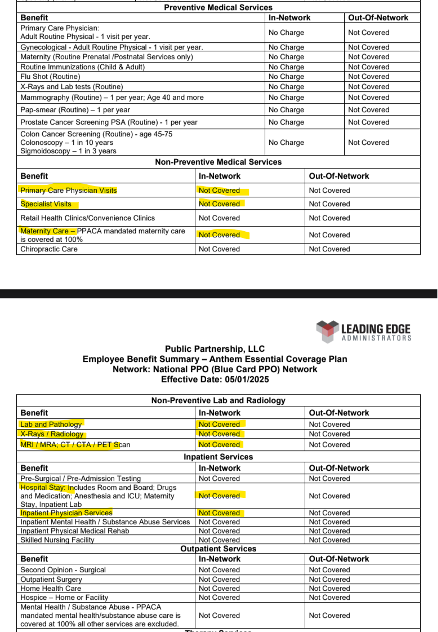

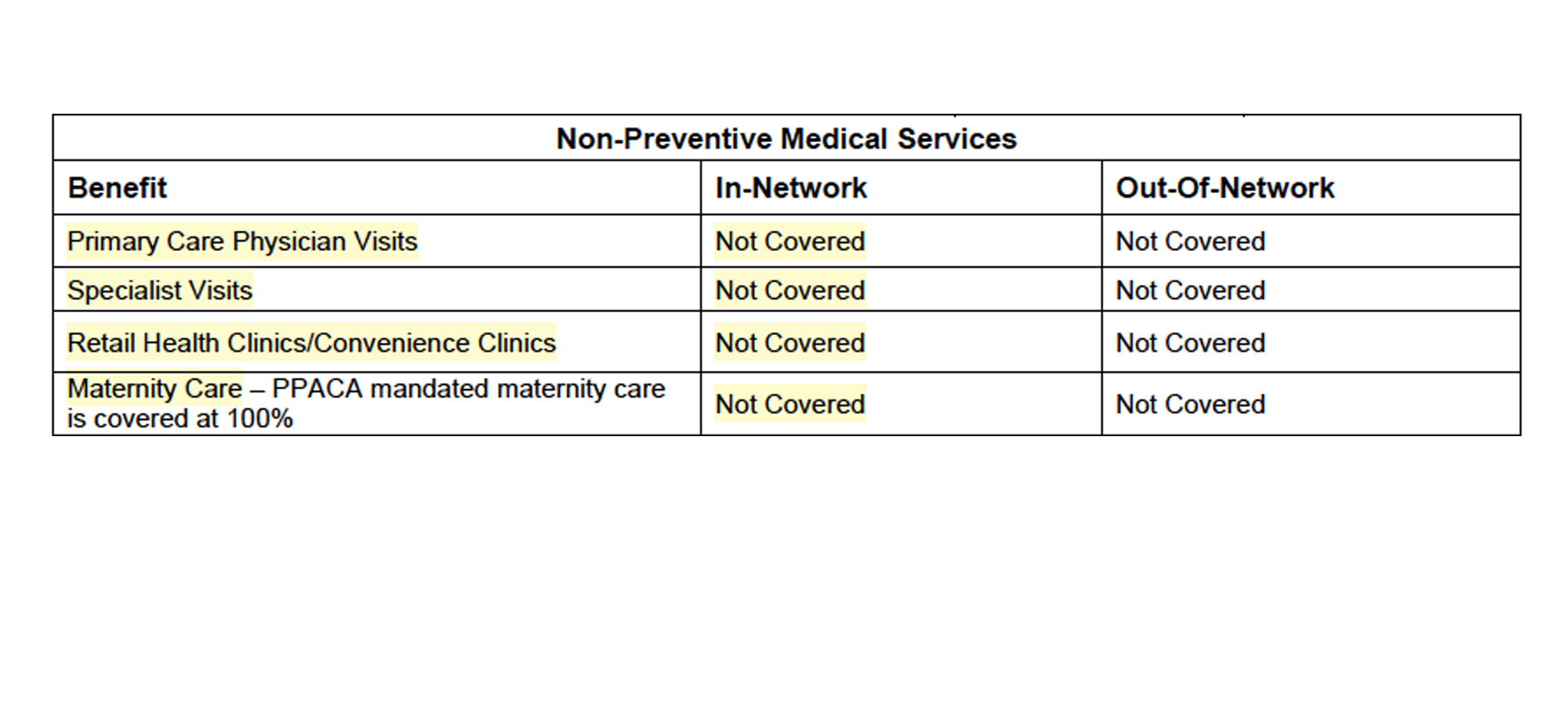

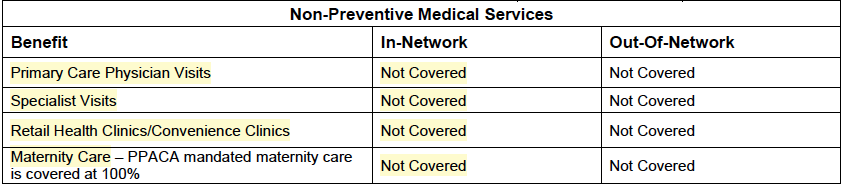

PPL will contribute $0.87 per hour for New York City workers and $1.03 per hour for workers in Westchester and Long Island to a “Minimum Essential Coverage” (MEC) plan offered in combination with a “Flex” card. (See NYC offer letter here.) Workers are being told that these plans are mandatory and there is no way to opt out. Astonishingly, plan documents indicate that the Minimum Essential Coverage plan provides no coverage at all for doctor’s visits, hospitalization, surgery, chemotherapy, maternity care or many other basic services. The MEC plan covers only a list of 10 preventive services (See Figure 1). An enrollee who gets cancer or suffers from diabetes or breaks a bone will receive no help at all from this plan.

Figure 1: Screenshot of PPL Plan Document for the Minimum Essential Coverage plan

Why would an employer offer such a plan? In essence, Minimum Essential Coverage plans are a way to avoid exposure to the ACA employer mandate. As a health insurance advisory presentation put it in a presentation to employers in 2015, “‘Skinny plans’ or ‘No minimum value plans’ are barebones plan designs whose genesis has come from a loophole in the healthcare law.”[3] The ACA requires large employers to provide some health coverage, but there’s a loophole: Employers can offer purely preventive care plans and avoid the most severe ACA penalties. (They won’t entirely escape penalties, however – see below.)

So there’s a benefit for PPL to offering MEC – but little benefit for workers. It is workers, however, who will pay the cost for this coverage. PPL is contributing $0.87 (NYC) or $1.03 (Long Island / Westchester) per hour to enroll every worker in this plan – even workers who work in home care only part-time and may have health insurance coverage from another employer. That works out to a contribution of nearly $2,000 per year for a full-time employee. PPL is funding this contribution using the wage parity supplement to workers’ wages – a state-mandated addition to wages which the state requires FIs to spend on wages or benefits, and which many FIs currently spend on wages. So, after the transition, many workers will see a wage cut of nearly a dollar in order to pay for health insurance coverage that does not cover hospitalization.

This is also a bad deal for state taxpayers. Taxpayers, after all, ultimately fund the home care program, so they will foot the bill for the MEC benefit. How much might it cost? I showed in a previous post that the state was paying for nearly 250 million hours of CDPAP home care in 2023, and by all accounts that number has continued to grow. Most CDPAP workers are downstate, in areas where they will be forced to enroll in the MEC plan. It is plausible that taxpayers could be spending as much as $300-400 million per year to offer this benefit.

Where might that money be going? It is not clear. The PPL-reported cost of MEC is far lower than that of “real” health insurance, which costs around $9,000 per worker per year, but of course MEC is not meaningful health insurance. Why is PPL charging nearly $2,000 per worker per year to enroll workers in a plan that doesn’t pay for basic services? Along with the MEC, PPL is also offering a “Flex” card (essentially a debit card with which workers can pay for certain types of out-of-pocket healthcare costs using pre-tax dollars), but no details on how much money will be on the Flex card have emerged so far. How the MEC contribution will be spent remains an open question.

Plan 2: The Minimum Value Plan

In addition to the mandatory MEC plan for downstate workers, PPL is also offering an optional “Minimum Value Plan.” Workers are being told that they will need to pay $212 for the plan (in addition to the mandatory MEC contribution for downstate workers.) The plan will be available only to workers who work at least 130 hours per month.

According to plan documents, this plan comes with a $6,350 individual deductible and covers nothing whatsoever beyond preventive services before the deductible is met. In other words, the first $6,350 of health costs a worker incurs will be paid entirely out of pocket. Even the lowest-cost Bronze plans available on New York’s ACA exchange provide vastly superior coverage.

To put that number in context, a CDPAP worker on Long Island who works 130 hours per month will earn approximately $30,400; under PPL’s plan, that worker would pay $2,544 in premiums for PPL’s Minimum Value plan, and would need to accumulate $6,350 in healthcare costs before beginning to benefit from the plan. In total, the worker would need to spend 29 percent of her income on healthcare costs before beginning to benefit from PPL’s plan.

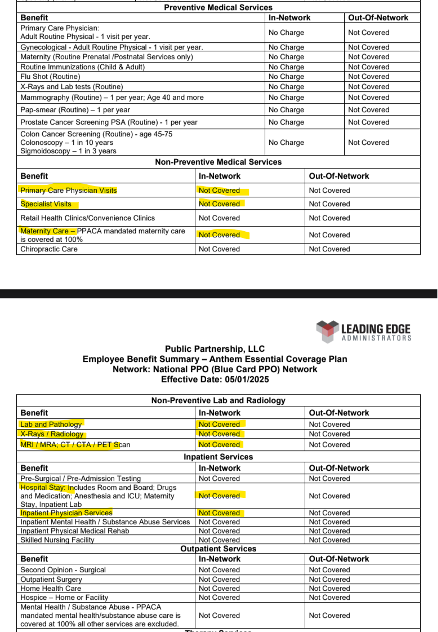

A separate concern regarding the “Minimum Value” plan has to do with its network. As mentioned above, PPL has publicly asserted that its health coverage will be provided by Anthem. Plan documents make clear that this is not the case: The plan will be administered by a Florida company called Leading Edge Administrators. The plan documents assert that the plan will use Anthem’s provider network, and “renting” a provider network is common practice in the health insurance industry. However, the plan documents also say that the plan will use a so-called “Beyond Value Plan Benefit payment pricing of 150% of the Medicare Allowable rate” for most inpatient services. This seems to indicate that the plan will pay providers, not at the rate agreed between Anthem and the providers, but at a set rate, 150% of the Medicare price – a rate far lower than that typically paid by commercial insurers. It is not clear that any providers will accept this lower rate, so it is not clear what providers will accept PPL’s plan as in-network.

Why is PPL offering such a shoddy plan? Again, the answer appears to be PPL’s desire to avoid ACA penalties. While offering a bare-bones MEC plan allows employers to avoid one form of ACA penalty (referred to as “Penalty A” in the industry), it leaves them exposed to a different penalty (“Penalty B”).[4] To avoid Penalty B, employers must not only offer health insurance, they must offer health insurance that is affordable and of minimum value under ACA standards. These standards are fairly low: A plan can count as “affordable” if it costs less than roughly 9.5% of a worker’s income, and it offers “minimum value” if it pays 60% of healthcare costs on average – equivalent to the worst possible ACA Bronze-tier plan.

PPL’s “Minimum Value” offering appears to be designed to just barely clear these hurdles, offering workers the worst and most expensive coverage it can offer while still allowing PPL to avoid ACA penalties.

This interpretation of PPL’s offer is confirmed by PPL’s own health benefits administrator, Leading Edge. In a recent interview with a trade publication, Mayer Majer, explained the strategy as follows:

<< Question 1: How can home care agencies assess the best health insurance options, considering the unique challenges they face?

If your company is an ALE (applicable large employer), you are required to offer your aides a Minimum Value plan. However, all health insurance carriers have a participation requirement which home care agencies will not meet.

There are options that we offer our clients. We have access to carriers who will allow a Minimum Value plan to be offered without any participation requirements as long as everyone receives a Minimal Essential Coverage plan.>>[5]

The purpose of the MV and MEC plans is not to provide healthcare, but to avoid ACA penalties.

PPL’s Healthcare Offer Will Cause Workers to Lose Existing Coverage

Some will argue that PPL’s offer, no matter how skimpy, is still an improvement over the status quo. After all, most existing FIs offer no health benefits at all; workers may not benefit much, but at least they’re no worse off.

This is incorrect. Many CDPAP workers currently receive high-quality, comprehensive, free or nearly free health insurance – and they will lose this coverage due to PPL’s offer.

Where do workers currently obtain coverage? A partial list would include:

The New York Essential Plan: New York’s Essential Plan is a state-federal program that offers free, zero-deductible healthcare to people making up to 250 percent of the federal poverty line (FPL) who are not eligible for Medicaid. It currently enrolls 1.65 million people. Most full-time CDPAP workers are well above the income limits for Medicaid, but are eligible for the Essential Plan, and many are likely enrolled.

Unfortunately for them, due to federal rules, anyone who receives an ACA-compliant offer of insurance from an employer is no longer eligible for the Essential Plan. The fact that PPL offers a Minimum Value Plan means that workers can’t stay on the Essential Plan, even if they don’t enroll in PPL’s plan.

Needless to say, workers currently enrolled in the Essential Plan will be much worse off once PPL takes over. Right now they receive free, zero-deductible coverage from the state; after PPL offers them health insurance, they’ll face a choice between paying out the nose for a plan with a $6,350 deductible or remaining uninsured.

The ACA Exchange: New York’s ACA exchange enrolls 218,000 people who are above the income eligibility level for the Essential Plan (250 percent of the FPL). Many enrollees receive substantial tax credits to help pay for coverage. Few home care workers earn more than 250 percent of the FPL from home care work alone, but those living in households with other sources of income may qualify. These workers will lose eligibility for subsidies and many will go uninsured.

Spousal coverage and retiree benefits: Many people who don’t receive insurance through their own employer receive it through a spouse’s employer. But many employer-sponsored health insurance policies cover a spouse only if the spouse does not have insurance available from his or her own employer (a so-called “working spouse rule”). So, once PPL offers health insurance, many people will become ineligible for their spouse’s insurance.

Likewise, some retiree health benefits apply only to people who are not currently working. This is especially common for public-sector workers: If you work as a firefighter or civil servant and retire at 60, your previous employer may continue to cover your health insurance, but only if you don’t get a new job that offers health insurance. Here, again, CDPAP workers may lose coverage they currently have.

Medicaid Managed Care: Some CDPAP workers are enrolled in Medicaid. While PPL’s offer of health insurance will not impact their eligibility for Medicaid, their mandatory enrollment in PPL’s MEC plan may result in them being automatically disenrolled from their current Medicaid Managed Care plan. This would be disruptive, confusing and might render some of their current providers out of network, causing gaps in care.

PPL’s Mandatory MEC Enrollment Will Create Confusion and Chaos

Loss of coverage is the largest, but not the only, problem with PPL’s healthcare plan. Disrupting health insurance for hundreds of thousands of people and forcing them to enroll in new coverage could create a number of other problems.

First, PPL’s mandatory MEC enrollment may cause workers to believe that they don’t need, or aren’t eligible for, other coverage – even when that’s not true. Most people who aren’t healthcare experts struggle to read and understand health insurance documents. Many CDPAP workers may hear that they’re being automatically enrolled in an insurance plan supposedly offered by Anthem, believe they’re covered, and fail to seek other coverage; these workers will realize that they have no meaningful health insurance only when they fall ill. Other workers may recognize that MEC isn’t meaningful health insurance but wrongly believe that it makes them ineligible for alternatives like Medicaid.

Second, PPL’s mandatory MEC enrollment will create a paperwork and bureaucratic nightmare for workers who retain other health insurance. For example, Medicare or Medicare Advantage enrollees who are also enrolled in the MEC will face confusing barriers to care: When they access primary care, does Medicare pay or does the MEC? If their current primary care physician is in their Medicare Advantage plan’s network but not in the MEC’s, can they continue seeing her?

Again, this is a very partial list of issues; enrolling hundreds of thousands of people in a bizarre health plan overnight (a plan whose terms are still not publicly available) will create many problems.

PPL’s MEC Plan Violates the Spirit of the Wage Parity Law

Since 2011, New York State has required home care employers to pay a home care minimum wage (somewhat higher than the statewide minimum wage) and a “wage parity supplement.” For example, CDPAP FIs in New York City are required to pay a $19.10 minimum wage, plus an additional $2.54 in wages or benefits.

Currently, most CDPAP FIs do not provide many benefits, so workers receive most of this money directly in wages. That is often preferable for workers, since, as we have seen, low-income workers who don’t have access to healthcare from an employer can often access high-quality healthcare elsewhere.

PPL, however, is using $0.89 of this $2.54 wage parity supplement (in New York City) and $1.03 of the $1.67 supplement in Westchester and Long Island to pay for its MEC plan on behalf of workers. As we have seen, the MEC plan benefits PPL as the employer by allowing it to avoid ACA penalties, but it provides very little benefit to workers. PPL is in effect using wage parity funding for its own advantage. This may or may not be legal under the letter of the wage parity law, but it is a gross violation of the spirit of the law.

Employer Status and Insurance Access in Home Care

The effect of PPL’s decision to offer health insurance will likely be to leave some home care workers without insurance while forcing others to leave the industry. Many CDPAP workers care for friends and relatives who wouldn’t be able to find caregivers otherwise; these workers will be trapped in the program, unable to afford PPL’s insurance, and lose access to healthcare. Other workers, who are able to find work in a different industry or in non-CDPAP home care, will simply opt out. That’s particularly likely given that PPL’s MEC offering will reduce wages for many workers relative to what they were being paid before the transition.

To be clear, this is not in PPL’s best interests; PPL is the single statewide fiscal intermediary for CDPAP, and will benefit if CDPAP continues to grow. It would appear that PPL believes that the ACA requires it to offer health insurance. Existing FIs have made a different assessment: Many believe, and have successfully persuaded the federal government, that they do not count as employers under the Affordable Care Act. That’s because FIs share many of the roles and responsibilities of an employer with consumers, who hire, fire and direct the work of their own home care workers.

It would appear that PPL has come to a different conclusion – it believes that it is subject to the ACA employer mandate, or at least that the risk that it may be subject to the ACA is sufficiently significant to justify cutting worker wages and limiting their access to healthcare. It is not clear why PPL would have a different legal status from previous FIs, and PPL and the state owe workers an explanation of how this assessment was arrived at.

In the meantime, the statewide transition to PPL on April 1 risks being a catastrophe for home care workers – lowering wages while eliminating health insurance coverage for tens or even hundreds of thousands of workers. Neither PPL nor the state has offered any explanation of why this is happening or what PPL intends to do about it; many workers are currently seeking information about whether they will still have health insurance on April 1. Under the circumstances, the state should pause the transition until PPL can offer a better explanation of its insurance offerings and how they serve the interests of Medicaid beneficiaries and healthcare workers.

Sources

[1] To my knowledge no accurate data exists on how many people work as personal assistances in the CDPAP program, but many consumers rely on more than one aide and 400,000 is a widely quoted estimate.

[2] PPL NY FAQ accessed at https://pplfirst.com/programs/new-york/ny-consumer-directed-personal-assistance-program-cdpap/ . The New York Department of Health has also claimed that PPL will offer health benefits; see 3/10/25 press release from NYSDOH, accessed at https://www.health.ny.gov/press/releases/2025/2025-03-10_cdpap.htm .

[3] https://board.coveredca.com/meetings/2015/1-15/Innovative%20MEC.pdf

[4] Full discussion of the ACA employer mandate is beyond the scope of this piece, but interested readers may consult this writeup: https://www.shrm.org/topics-tools/tools/hr-answers/employer-shared-responsibility-penalties-patient-protection-affordable-care-act-ppaca

[5] https://www.caresmartz360.com/home-care-expert-insights/mayer-majer/

How the CDPAP Transition Could Leave Thousands of Home Care Workers Uninsured

March 17, 2025 |

Key Findings

- New York State’s new home care fiscal intermediary plans to require workers in downstate areas to pay between $0.87 and $1.06 per hour to enroll in a health plan that doesn’t cover basic services like primary care and hospital visits.

- Workers statewide will have the option to pay over $200 per month to enroll in a plan with a $6,350 deductible that covers little before the deductible.

- Most disturbingly, these health insurance offers may cause workers to lose their existing health insurance. These offerings may mean that many workers who were previously eligible for coverage through the New York Essential Plan, a spouse’s plan, or an employer’s retirement plan will lose access to their existing coverage – which in virtually all cases would be far better than the coverage PPL is offering.

- PPL appears to be offering this weak coverage in order to avoid tax penalties it would otherwise owe under the Affordable Care Act.

- PPL’s health insurance offer may cause hundreds of thousands of workers to lose health insurance.

Introduction

The transition of New York’s Medicaid-funded Consumer-Directed Personal Assistance Program (CDPAP) to a single fiscal intermediary has been extremely controversial. The program, which provides home care to 280,000 elderly and disabled New Yorkers and employs as many as 400,000 workers,[1] is currently operated by around 600 fiscal intermediaries (FIs), who handle payroll and benefits for workers. Last year’s state budget mandated that the program be transitioned to a single, statewide FI by April 1, 2025, and this summer the state selected a Georgia-based company called Public Partnerships, LLC (PPL) as the new single FI.

The transition has been controversial, with proponents arguing that a single FI can administer the program more efficiently while opponents worry that consumers may lose benefits. The timeline of the transition has been doubly controversial: The state announced on March 10 that only 115,000 out of 280,000 consumers had “started or completed” the registration process with PPL, raising the possibility that thousands will not register in time for the April 1 deadline. Advocates continue to plead with the state to delay.

What has not become clear until very recently is that the transition may cause many workers to earn lower wages and lose access to health insurance. As I will discuss in this piece, PPL’s offer of coverage leaves workers much worse off than if PPL simply offered no health insurance at all; not only does it cover very little and cost workers a lot, but it will render them ineligible for the high-quality insurance many currently enjoy.

The PPL Healthcare Offer

PPL has been extremely vague about its plans for worker health insurance so far, saying only that workers downstate would be enrolled in its “PPL Minimum Essentials Coverage Preventive Plan (MEC Plan)” and that workers statewide would have the option to “a competitive benefits package that includes health insurance” with “benefits provided by Anthem.”[2] Since most current CDPAP FIs offer no health insurance at all, these offers sounded promising.

As workers have begun to receive further information, however, the details of PPL’s offer have become increasingly disturbing. Plan documents show that PPL’s health insurance offering is disturbingly bad.

PPL is offering two health insurance packages: A “Minimum Essential Coverage” package for downstate workers, with mandatory enrollment, and a “Minimum Value” plan for workers throughout the state, which workers can pay extra for. We will describe each in turn.

Plan 1: Minimum Essential Coverage

PPL will contribute $0.87 per hour for New York City workers and $1.03 per hour for workers in Westchester and Long Island to a “Minimum Essential Coverage” (MEC) plan offered in combination with a “Flex” card. (See NYC offer letter here.) Workers are being told that these plans are mandatory and there is no way to opt out. Astonishingly, plan documents indicate that the Minimum Essential Coverage plan provides no coverage at all for doctor’s visits, hospitalization, surgery, chemotherapy, maternity care or many other basic services. The MEC plan covers only a list of 10 preventive services (See Figure 1). An enrollee who gets cancer or suffers from diabetes or breaks a bone will receive no help at all from this plan.

Figure 1: Screenshot of PPL Plan Document for the Minimum Essential Coverage plan

Why would an employer offer such a plan? In essence, Minimum Essential Coverage plans are a way to avoid exposure to the ACA employer mandate. As a health insurance advisory presentation put it in a presentation to employers in 2015, “‘Skinny plans’ or ‘No minimum value plans’ are barebones plan designs whose genesis has come from a loophole in the healthcare law.”[3] The ACA requires large employers to provide some health coverage, but there’s a loophole: Employers can offer purely preventive care plans and avoid the most severe ACA penalties. (They won’t entirely escape penalties, however – see below.)

So there’s a benefit for PPL to offering MEC – but little benefit for workers. It is workers, however, who will pay the cost for this coverage. PPL is contributing $0.87 (NYC) or $1.03 (Long Island / Westchester) per hour to enroll every worker in this plan – even workers who work in home care only part-time and may have health insurance coverage from another employer. That works out to a contribution of nearly $2,000 per year for a full-time employee. PPL is funding this contribution using the wage parity supplement to workers’ wages – a state-mandated addition to wages which the state requires FIs to spend on wages or benefits, and which many FIs currently spend on wages. So, after the transition, many workers will see a wage cut of nearly a dollar in order to pay for health insurance coverage that does not cover hospitalization.

This is also a bad deal for state taxpayers. Taxpayers, after all, ultimately fund the home care program, so they will foot the bill for the MEC benefit. How much might it cost? I showed in a previous post that the state was paying for nearly 250 million hours of CDPAP home care in 2023, and by all accounts that number has continued to grow. Most CDPAP workers are downstate, in areas where they will be forced to enroll in the MEC plan. It is plausible that taxpayers could be spending as much as $300-400 million per year to offer this benefit.

Where might that money be going? It is not clear. The PPL-reported cost of MEC is far lower than that of “real” health insurance, which costs around $9,000 per worker per year, but of course MEC is not meaningful health insurance. Why is PPL charging nearly $2,000 per worker per year to enroll workers in a plan that doesn’t pay for basic services? Along with the MEC, PPL is also offering a “Flex” card (essentially a debit card with which workers can pay for certain types of out-of-pocket healthcare costs using pre-tax dollars), but no details on how much money will be on the Flex card have emerged so far. How the MEC contribution will be spent remains an open question.

Plan 2: The Minimum Value Plan

In addition to the mandatory MEC plan for downstate workers, PPL is also offering an optional “Minimum Value Plan.” Workers are being told that they will need to pay $212 for the plan (in addition to the mandatory MEC contribution for downstate workers.) The plan will be available only to workers who work at least 130 hours per month.

According to plan documents, this plan comes with a $6,350 individual deductible and covers nothing whatsoever beyond preventive services before the deductible is met. In other words, the first $6,350 of health costs a worker incurs will be paid entirely out of pocket. Even the lowest-cost Bronze plans available on New York’s ACA exchange provide vastly superior coverage.

To put that number in context, a CDPAP worker on Long Island who works 130 hours per month will earn approximately $30,400; under PPL’s plan, that worker would pay $2,544 in premiums for PPL’s Minimum Value plan, and would need to accumulate $6,350 in healthcare costs before beginning to benefit from the plan. In total, the worker would need to spend 29 percent of her income on healthcare costs before beginning to benefit from PPL’s plan.

A separate concern regarding the “Minimum Value” plan has to do with its network. As mentioned above, PPL has publicly asserted that its health coverage will be provided by Anthem. Plan documents make clear that this is not the case: The plan will be administered by a Florida company called Leading Edge Administrators. The plan documents assert that the plan will use Anthem’s provider network, and “renting” a provider network is common practice in the health insurance industry. However, the plan documents also say that the plan will use a so-called “Beyond Value Plan Benefit payment pricing of 150% of the Medicare Allowable rate” for most inpatient services. This seems to indicate that the plan will pay providers, not at the rate agreed between Anthem and the providers, but at a set rate, 150% of the Medicare price – a rate far lower than that typically paid by commercial insurers. It is not clear that any providers will accept this lower rate, so it is not clear what providers will accept PPL’s plan as in-network.

Why is PPL offering such a shoddy plan? Again, the answer appears to be PPL’s desire to avoid ACA penalties. While offering a bare-bones MEC plan allows employers to avoid one form of ACA penalty (referred to as “Penalty A” in the industry), it leaves them exposed to a different penalty (“Penalty B”).[4] To avoid Penalty B, employers must not only offer health insurance, they must offer health insurance that is affordable and of minimum value under ACA standards. These standards are fairly low: A plan can count as “affordable” if it costs less than roughly 9.5% of a worker’s income, and it offers “minimum value” if it pays 60% of healthcare costs on average – equivalent to the worst possible ACA Bronze-tier plan.

PPL’s “Minimum Value” offering appears to be designed to just barely clear these hurdles, offering workers the worst and most expensive coverage it can offer while still allowing PPL to avoid ACA penalties.

This interpretation of PPL’s offer is confirmed by PPL’s own health benefits administrator, Leading Edge. In a recent interview with a trade publication, Mayer Majer, explained the strategy as follows:

<< Question 1: How can home care agencies assess the best health insurance options, considering the unique challenges they face?

If your company is an ALE (applicable large employer), you are required to offer your aides a Minimum Value plan. However, all health insurance carriers have a participation requirement which home care agencies will not meet.

There are options that we offer our clients. We have access to carriers who will allow a Minimum Value plan to be offered without any participation requirements as long as everyone receives a Minimal Essential Coverage plan.>>[5]

The purpose of the MV and MEC plans is not to provide healthcare, but to avoid ACA penalties.

PPL’s Healthcare Offer Will Cause Workers to Lose Existing Coverage

Some will argue that PPL’s offer, no matter how skimpy, is still an improvement over the status quo. After all, most existing FIs offer no health benefits at all; workers may not benefit much, but at least they’re no worse off.

This is incorrect. Many CDPAP workers currently receive high-quality, comprehensive, free or nearly free health insurance – and they will lose this coverage due to PPL’s offer.

Where do workers currently obtain coverage? A partial list would include:

The New York Essential Plan: New York’s Essential Plan is a state-federal program that offers free, zero-deductible healthcare to people making up to 250 percent of the federal poverty line (FPL) who are not eligible for Medicaid. It currently enrolls 1.65 million people. Most full-time CDPAP workers are well above the income limits for Medicaid, but are eligible for the Essential Plan, and many are likely enrolled.

Unfortunately for them, due to federal rules, anyone who receives an ACA-compliant offer of insurance from an employer is no longer eligible for the Essential Plan. The fact that PPL offers a Minimum Value Plan means that workers can’t stay on the Essential Plan, even if they don’t enroll in PPL’s plan.

Needless to say, workers currently enrolled in the Essential Plan will be much worse off once PPL takes over. Right now they receive free, zero-deductible coverage from the state; after PPL offers them health insurance, they’ll face a choice between paying out the nose for a plan with a $6,350 deductible or remaining uninsured.

The ACA Exchange: New York’s ACA exchange enrolls 218,000 people who are above the income eligibility level for the Essential Plan (250 percent of the FPL). Many enrollees receive substantial tax credits to help pay for coverage. Few home care workers earn more than 250 percent of the FPL from home care work alone, but those living in households with other sources of income may qualify. These workers will lose eligibility for subsidies and many will go uninsured.

Spousal coverage and retiree benefits: Many people who don’t receive insurance through their own employer receive it through a spouse’s employer. But many employer-sponsored health insurance policies cover a spouse only if the spouse does not have insurance available from his or her own employer (a so-called “working spouse rule”). So, once PPL offers health insurance, many people will become ineligible for their spouse’s insurance.

Likewise, some retiree health benefits apply only to people who are not currently working. This is especially common for public-sector workers: If you work as a firefighter or civil servant and retire at 60, your previous employer may continue to cover your health insurance, but only if you don’t get a new job that offers health insurance. Here, again, CDPAP workers may lose coverage they currently have.

Medicaid Managed Care: Some CDPAP workers are enrolled in Medicaid. While PPL’s offer of health insurance will not impact their eligibility for Medicaid, their mandatory enrollment in PPL’s MEC plan may result in them being automatically disenrolled from their current Medicaid Managed Care plan. This would be disruptive, confusing and might render some of their current providers out of network, causing gaps in care.

PPL’s Mandatory MEC Enrollment Will Create Confusion and Chaos

Loss of coverage is the largest, but not the only, problem with PPL’s healthcare plan. Disrupting health insurance for hundreds of thousands of people and forcing them to enroll in new coverage could create a number of other problems.

First, PPL’s mandatory MEC enrollment may cause workers to believe that they don’t need, or aren’t eligible for, other coverage – even when that’s not true. Most people who aren’t healthcare experts struggle to read and understand health insurance documents. Many CDPAP workers may hear that they’re being automatically enrolled in an insurance plan supposedly offered by Anthem, believe they’re covered, and fail to seek other coverage; these workers will realize that they have no meaningful health insurance only when they fall ill. Other workers may recognize that MEC isn’t meaningful health insurance but wrongly believe that it makes them ineligible for alternatives like Medicaid.

Second, PPL’s mandatory MEC enrollment will create a paperwork and bureaucratic nightmare for workers who retain other health insurance. For example, Medicare or Medicare Advantage enrollees who are also enrolled in the MEC will face confusing barriers to care: When they access primary care, does Medicare pay or does the MEC? If their current primary care physician is in their Medicare Advantage plan’s network but not in the MEC’s, can they continue seeing her?

Again, this is a very partial list of issues; enrolling hundreds of thousands of people in a bizarre health plan overnight (a plan whose terms are still not publicly available) will create many problems.

PPL’s MEC Plan Violates the Spirit of the Wage Parity Law

Since 2011, New York State has required home care employers to pay a home care minimum wage (somewhat higher than the statewide minimum wage) and a “wage parity supplement.” For example, CDPAP FIs in New York City are required to pay a $19.10 minimum wage, plus an additional $2.54 in wages or benefits.

Currently, most CDPAP FIs do not provide many benefits, so workers receive most of this money directly in wages. That is often preferable for workers, since, as we have seen, low-income workers who don’t have access to healthcare from an employer can often access high-quality healthcare elsewhere.

PPL, however, is using $0.89 of this $2.54 wage parity supplement (in New York City) and $1.03 of the $1.67 supplement in Westchester and Long Island to pay for its MEC plan on behalf of workers. As we have seen, the MEC plan benefits PPL as the employer by allowing it to avoid ACA penalties, but it provides very little benefit to workers. PPL is in effect using wage parity funding for its own advantage. This may or may not be legal under the letter of the wage parity law, but it is a gross violation of the spirit of the law.

Employer Status and Insurance Access in Home Care

The effect of PPL’s decision to offer health insurance will likely be to leave some home care workers without insurance while forcing others to leave the industry. Many CDPAP workers care for friends and relatives who wouldn’t be able to find caregivers otherwise; these workers will be trapped in the program, unable to afford PPL’s insurance, and lose access to healthcare. Other workers, who are able to find work in a different industry or in non-CDPAP home care, will simply opt out. That’s particularly likely given that PPL’s MEC offering will reduce wages for many workers relative to what they were being paid before the transition.

To be clear, this is not in PPL’s best interests; PPL is the single statewide fiscal intermediary for CDPAP, and will benefit if CDPAP continues to grow. It would appear that PPL believes that the ACA requires it to offer health insurance. Existing FIs have made a different assessment: Many believe, and have successfully persuaded the federal government, that they do not count as employers under the Affordable Care Act. That’s because FIs share many of the roles and responsibilities of an employer with consumers, who hire, fire and direct the work of their own home care workers.

It would appear that PPL has come to a different conclusion – it believes that it is subject to the ACA employer mandate, or at least that the risk that it may be subject to the ACA is sufficiently significant to justify cutting worker wages and limiting their access to healthcare. It is not clear why PPL would have a different legal status from previous FIs, and PPL and the state owe workers an explanation of how this assessment was arrived at.

In the meantime, the statewide transition to PPL on April 1 risks being a catastrophe for home care workers – lowering wages while eliminating health insurance coverage for tens or even hundreds of thousands of workers. Neither PPL nor the state has offered any explanation of why this is happening or what PPL intends to do about it; many workers are currently seeking information about whether they will still have health insurance on April 1. Under the circumstances, the state should pause the transition until PPL can offer a better explanation of its insurance offerings and how they serve the interests of Medicaid beneficiaries and healthcare workers.

Sources

[1] To my knowledge no accurate data exists on how many people work as personal assistances in the CDPAP program, but many consumers rely on more than one aide and 400,000 is a widely quoted estimate.

[2] PPL NY FAQ accessed at https://pplfirst.com/programs/new-york/ny-consumer-directed-personal-assistance-program-cdpap/ . The New York Department of Health has also claimed that PPL will offer health benefits; see 3/10/25 press release from NYSDOH, accessed at https://www.health.ny.gov/press/releases/2025/2025-03-10_cdpap.htm .

[3] https://board.coveredca.com/meetings/2015/1-15/Innovative%20MEC.pdf

[4] Full discussion of the ACA employer mandate is beyond the scope of this piece, but interested readers may consult this writeup: https://www.shrm.org/topics-tools/tools/hr-answers/employer-shared-responsibility-penalties-patient-protection-affordable-care-act-ppaca

[5] https://www.caresmartz360.com/home-care-expert-insights/mayer-majer/