The Healthcare Stand-off

March 26, 2024 |

Executive and Legislature at Odds Over Medicaid

Introduction

The one-house budgets reflect a sharp disagreement between the Governor and the legislature on Medicaid spending. The executive budget proposes sharp cuts to several areas of Medicaid spending — most notably home care worker wages — and provides only limited support for financially distressed hospitals.

The Senate and Assembly one-house budgets soundly reject the executive’s approach. Both houses’ budget proposals reject virtually all of the executive budget’s cuts and instead propose substantial rate increases, particularly for hospitals and nursing homes. To pay for their proposals, the one-house budgets propose a new Medicaid tax that would generate $4 billion in additional federal revenue. This proposal represents a smart way to bridge the gap in spending next year and avoid the drastic cuts proposed by the executive; however, in the long term the State must consider more permanent reform and funding mechanisms for its Medicaid program.

Medicaid:

The legislature rejected cuts and proposed significant new funding, resulting in significantly higher Medicaid spending

The Assembly budget proposes $7.1 billion more in state-share Medicaid spending than the executive budget. The Senate’s overall Medicaid spending appears similar. This sum represents by far the largest single difference between the executive budget and the legislature’s proposals. While roughly $3.1 billion of the legislature’s spending would be reinvested to compensate managed care organizations for their payment of the Managed Care Organization Tax (see below), the remaining $4 billion is used to reverse the executive budget’s proposed cuts and offer significant rate increases to providers.

While the executive budget purports to increase Medicaid spending by about $3 billion, this increase in spending is also met by large cuts to home care and nursing care in the state that amount to $1.2 billion. The Senate and Assembly proposals not only reverse these cuts, but also propose to increase Medicaid reimbursement rates across hospitals, nursing homes, and other providers. The gap between the executive budget proposal — which not only fails to raise Medicaid rates but additionally cuts funding — and the Senate and Assembly proposals — which increase spending through rate increases (among other mechanisms) and reverse the executive budget cuts — leaves significant middle ground to be debated.

-

MCO Tax: Legislature proposes an MCO Tax to generate $4 billion in new federal revenue at no cost to New York

As described in a recent FPI brief, the legislature has proposed a Manage Care Organization Tax (MCO Tax) that will generate $4 billion per year in increased federal revenue.[1] This tax will fall primarily on Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs), private insurance plans which administer healthcare for the vast majority of New York’s Medicaid beneficiaries.[2] MCOs will be taxed and then reimbursed by the State for their share of the tax, allowing the state to draw down federal Medicaid matching dollars; the State will generate approximately $7.1 billion in revenue, of which $3.1 billion will be used to reimburse the MCOs, leaving roughly $4 billion in new federal revenue to fund other programs.

This financing structure would need to be approved by the federal government, and receiving such approval would likely take at least six months. Federal regulators recently approved a similar mechanism in California, but indicated that they intend to issue new regulations disallowing it in the future. Thus, the MCO tax proposal faces two forms of uncertainty: In the short term, it is not clear whether the governor will agree to a budget that presumes approval of the MCO tax. In the long term, if the tax is enacted, the State may find that changes in federal regulation render it ineffective in the future and may be forced to seek other sources of revenue.

Despite these uncertainties, the MCO tax provides crucial funding at no cost to New York State taxpayers. Thus, it may serve New York well as a source of funding while longer-term solutions to the State’s healthcare woes are developed.

-

Long-Term Care: The legislature reverses cuts proposed by the executive but does not reform the MLTC program

The cost of providing long-term care to Medicaid recipients is one of the largest drivers of cost increases in the State’s Medicaid budget. As FPI has previously reported, the need for home care has grown tremendously over recent years and will continue to grow as the Baby Boomer generation ages and increases demand for long-term care services.[3]

The executive budget proposes dramatic cuts to the State’s home care system, targeting Consumer-Directed Personal Assistance Program (CDPAP), the largest state home care program, in particular. The executive budget cuts wages for hundreds of thousands of CDPAP workers, imposes a cap on hours, and eliminates “Designated Representatives,” which would likely force tens of thousands of Medicaid beneficiaries out of CDPAP. The one-house budgets reject all of these changes and restore the program to its status quo.

Another site of controversy within the State’s long-term care system has been the Managed Long-Term Care (MLTC) program, which administers much of the state’s Medicaid home care system. Home care advocates and labor unions have argued that this program is wasteful and should be replaced. The executive budget does not adopt this proposal, but suggests more moderate reforms, including competitive procurement of MLTC MCOs and expanded power for the state to enforce MLTC contracts.

The one-house budgets reject the executive budget proposals for MLTC reform, but also decline to heed advocates’ call to eliminate MLTC programs altogether. Both houses included language expressing openness to the elimination of MLTC programs — with the Assembly explicitly calling for a shift away from managed care — but neither house proposes legislation to implement the change. It appears that the MLTC program will remain in limbo for another year, despite broad consensus on the need for reform.

-

Provider Rate Increases and Distressed Hospital Funding: Legislature proposes large increases to hospital and nursing home rates, along with operating and capital support for financially distressed hospitals

The legislature proposes dramatic Medicaid rate increases, heeding calls from provider associations and labor unions for increased funding. Each house includes a 3 percent across-the-board rate hike, plus additional rate increases for hospitals, nursing homes, and assisted living, bringing the total rate increases for those groups to around 10 percent at a cost of around $1.6 billion state share. The one-house budgets also reverse minor cuts to the hospital and nursing home capital rates.

Those rate increases would benefit all hospitals in the state but would not fully address the needs of the many financially distressed hospitals in New York; the executive budget describes nearly a third of the state’s hospitals as financially distressed and suggests billions of dollars in unmet need for operating support. To address this unmet need, the Assembly proposes $500 million in state spending and the Senate proposes $600 million in state operating support for financially distressed hospitals. This funding would likely support some Medicaid spending matched by federal dollars through the Directed Payment Template (DPT) program and some state-only spending through the Vital Access Provider Assurance Program.[4]

Increased operating funds will keep financially distressed hospitals on life support, but it is widely recognized that these hospitals need to invest in improved facilities and new service lines to survive in the long term. The executive budget addresses capital needs by reallocating $500 million in existing capital funding, with the bulk of that apparently intended to support SUNY Downstate’s closure. The capital funding proposed in the executive budget requires financially distressed hospitals to partner with other providers to receive funding. The legislative budgets increase the amount of funding available, with the Assembly providing $1 billion and the Senate proposing $2 billion in additional capital funding; they also drop the requirement that safety net hospitals partner with other institutions to seek funding.

SUNY Downstate: Executive budget proposes closing the hospital while both houses allocate funds towards sustaining it

In January 2024, SUNY announced a plan to close SUNY Downstate, a teaching hospital in Brooklyn. As part of the amended executive budget, the State committed $100 million in operating support and $300 million in capital funding to implement a “transformation plan,” a State-developed plan to relocate certain SUNY Downstate services to the adjacent Kings County Hospital Center, a City-supported hospital.

The Senate and Assembly both accept the executive budget’s proposed spending levels. The Senate, however, would make the capital funding conditional on a “sustainability plan.” The sustainability plan, which would be developed by a commission made up of executive, legislative, labor, and community appointees, would outline a strategy for retaining SUNY Downstate’s teaching and service capacity in five core medical practices defined by the Senate. Operating support would be used to support current services while the sustainability plan is finalized. The Assembly budget resolution expresses support for maintaining services at SUNY Downstate, though it does not include legislation conditioning capital funds.

Finally, both houses would add $79 million to support SUNY hospitals’ debt service, offsetting costs for the system’s three teaching hospitals, and $150 million in capital funding for SUNY hospitals.

Human Services Providers: Legislature proposes a significantly higher rate increase than the Executive

While the executive budget proposed an increase to the wages of 1.5 percent for non-profit human service providers, the Senate and Assembly both proposed a larger wage increase of 3.2 percent. Against the backdrop of inflation over the past three years, this cost of living adjustment is relatively small and may not do much to retain staff.

Conclusion

The legislature is wise to reject the Governor’s cuts to Medicaid and has identified a viable source of new federal revenue to support continued Medicaid growth. However, the legislature has missed an opportunity to reform New York’s home care delivery system by eliminating Managed Long Term Care and substituting a Managed Fee-for-Service arrangement, a move that could save the State billions of dollars. In addition, the legislature has not articulated a clear long-term vision for the role of safety-net hospitals and the best way to financially support them; in the absence of such a vision, increased funding is welcome, but the drumbeat of hospital closures will likely continue.

[1] https://fiscalpolicy.org/the-medicaid-mco-tax-strategy

[2] It is important to note that the state operates several Medicaid managed care programs, the largest of which (“Mainstream Managed Care”) provides Medicaid benefits to the vast majority of New York’s Medicaid beneficiaries. A smaller but expensive program, “Managed Long-Term Care,” provides home care to elderly and disabled New Yorkers. The MLTC program has been controversial, with advocates and labor unions calling for the elimination of MLTC MCOs. However, the MCO tax would likely generate most of its revenue from the Mainstream Managed Care program and would be a viable revenue option even if the MLTC program were eliminated.

[3] https://fiscalpolicy.org/workforce-report-labor-shortage-mitigation-in-new-yorks-home-care-sector

[4] See discussion at Step Two Policy Project https://22bd584a-fab4-4177-ba23-ab0417da452c.usrfiles.com/ugd/22bd58_824ee45ce42a41cabf287bd2f4aaa935.pdf

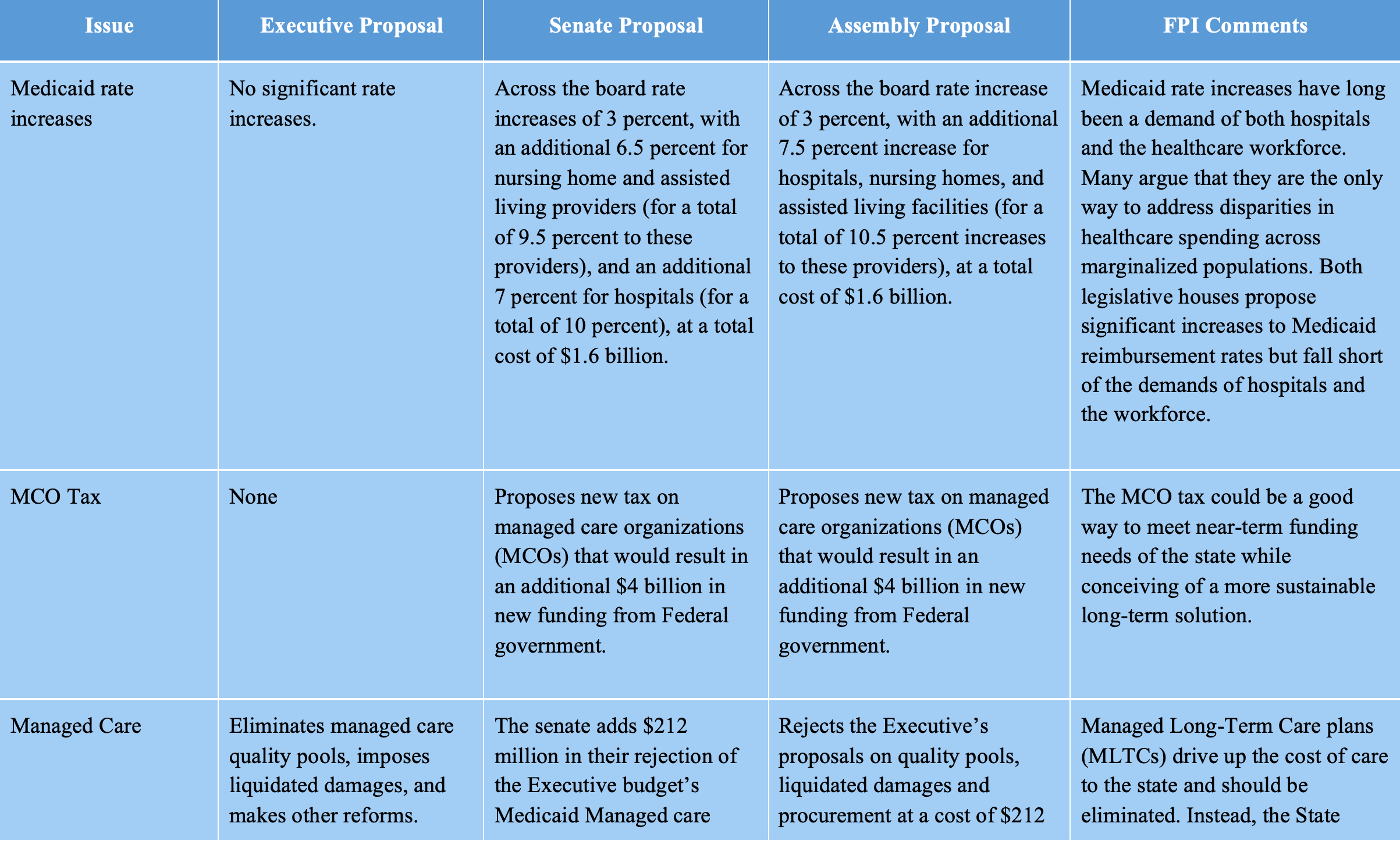

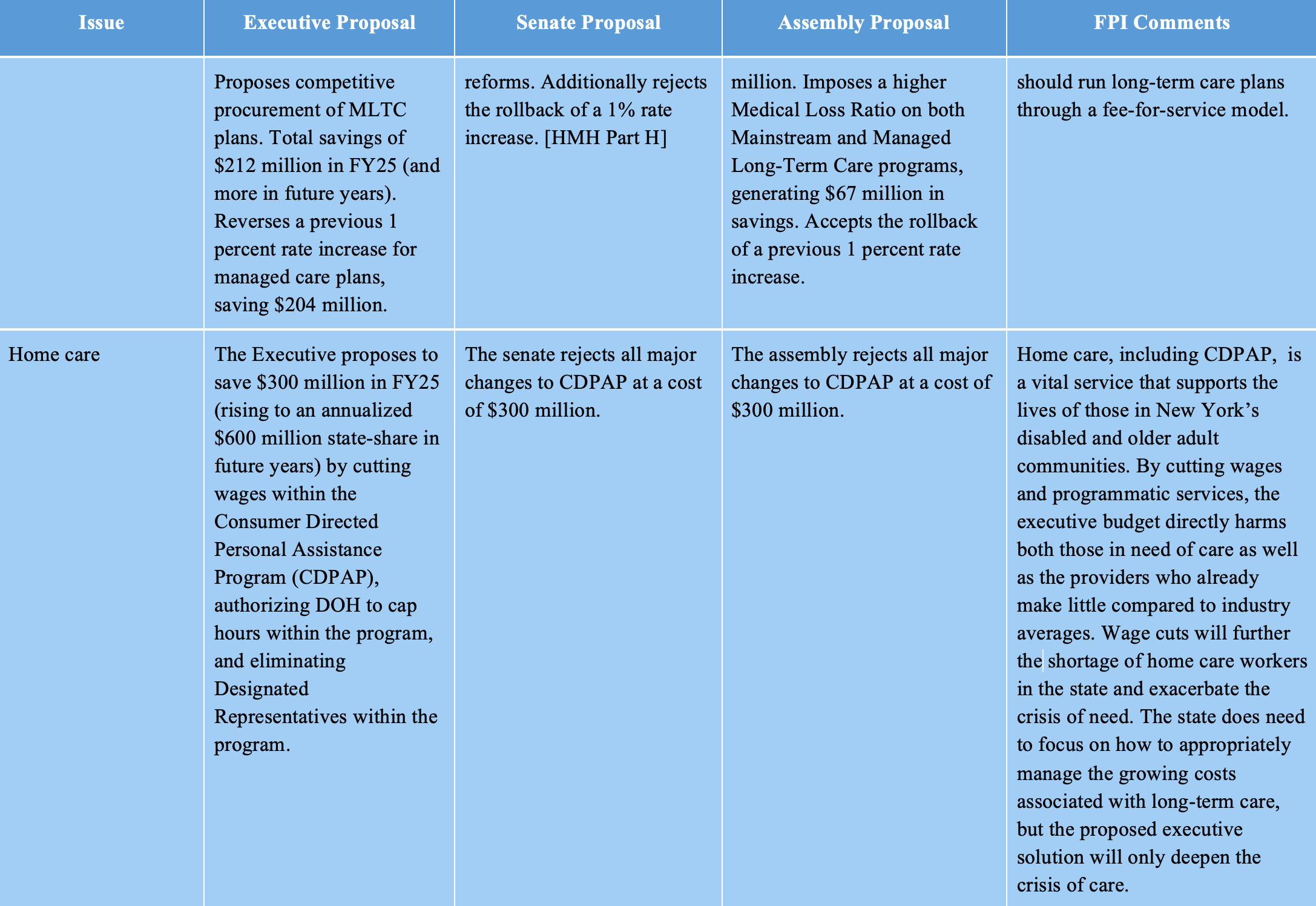

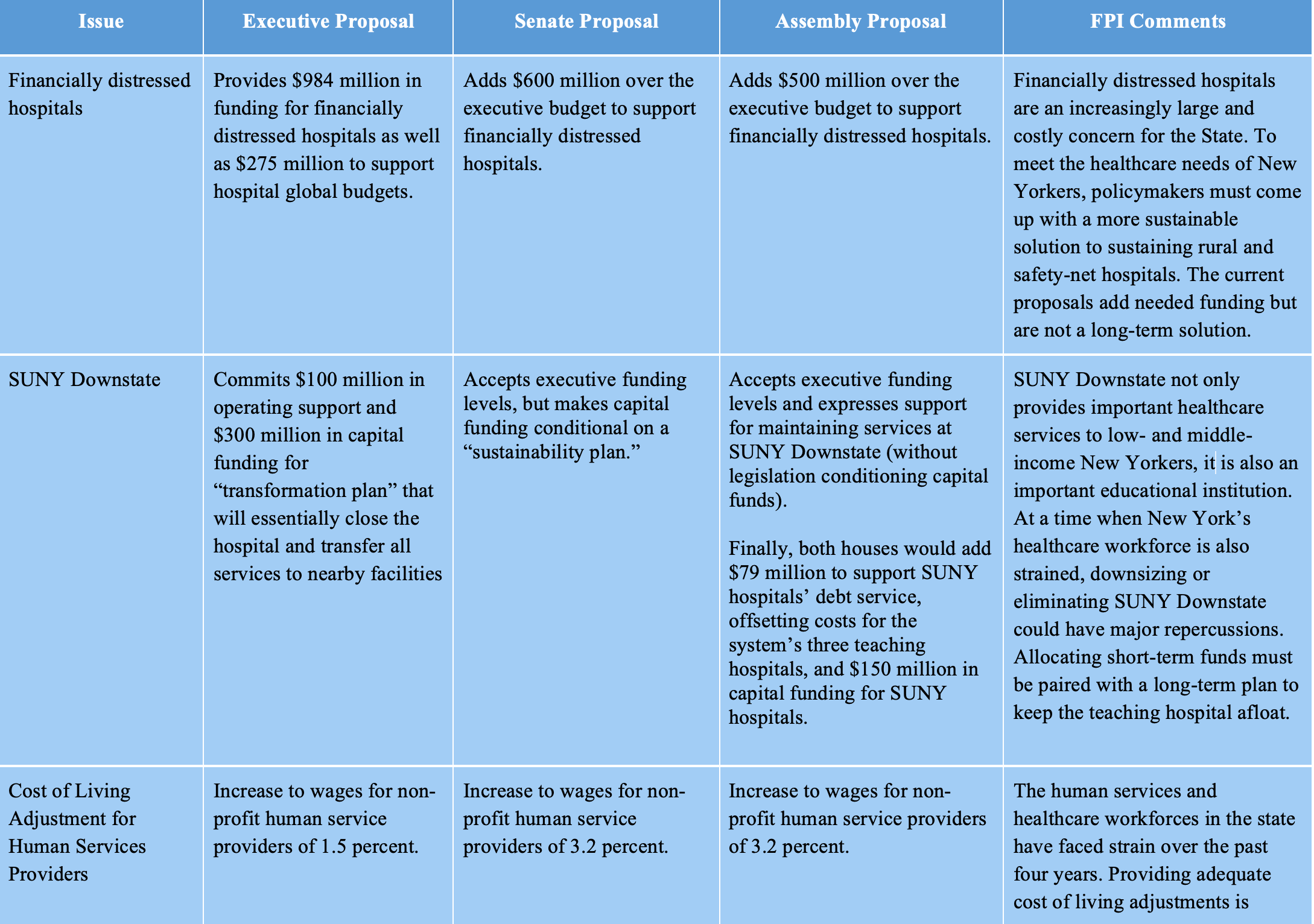

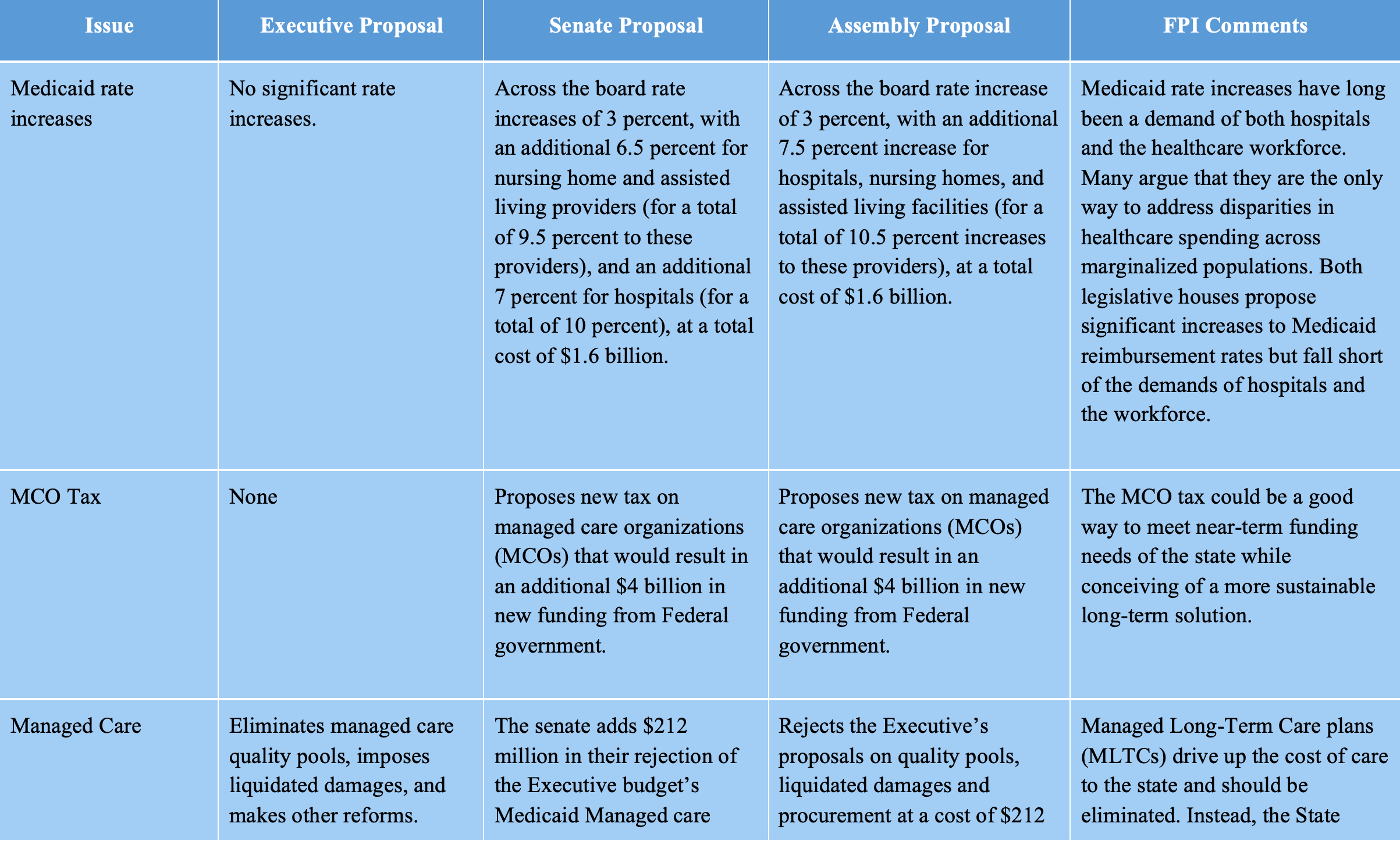

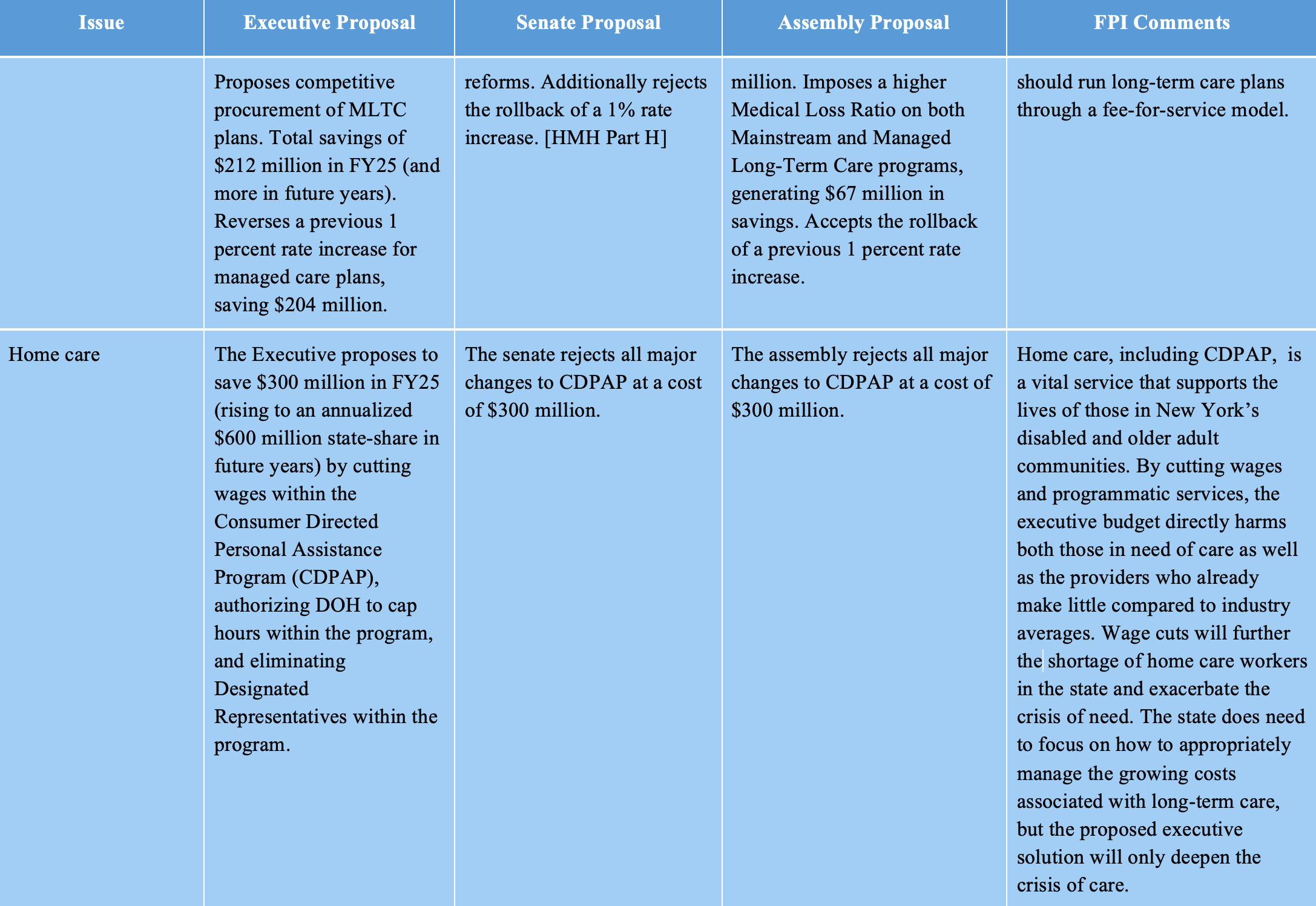

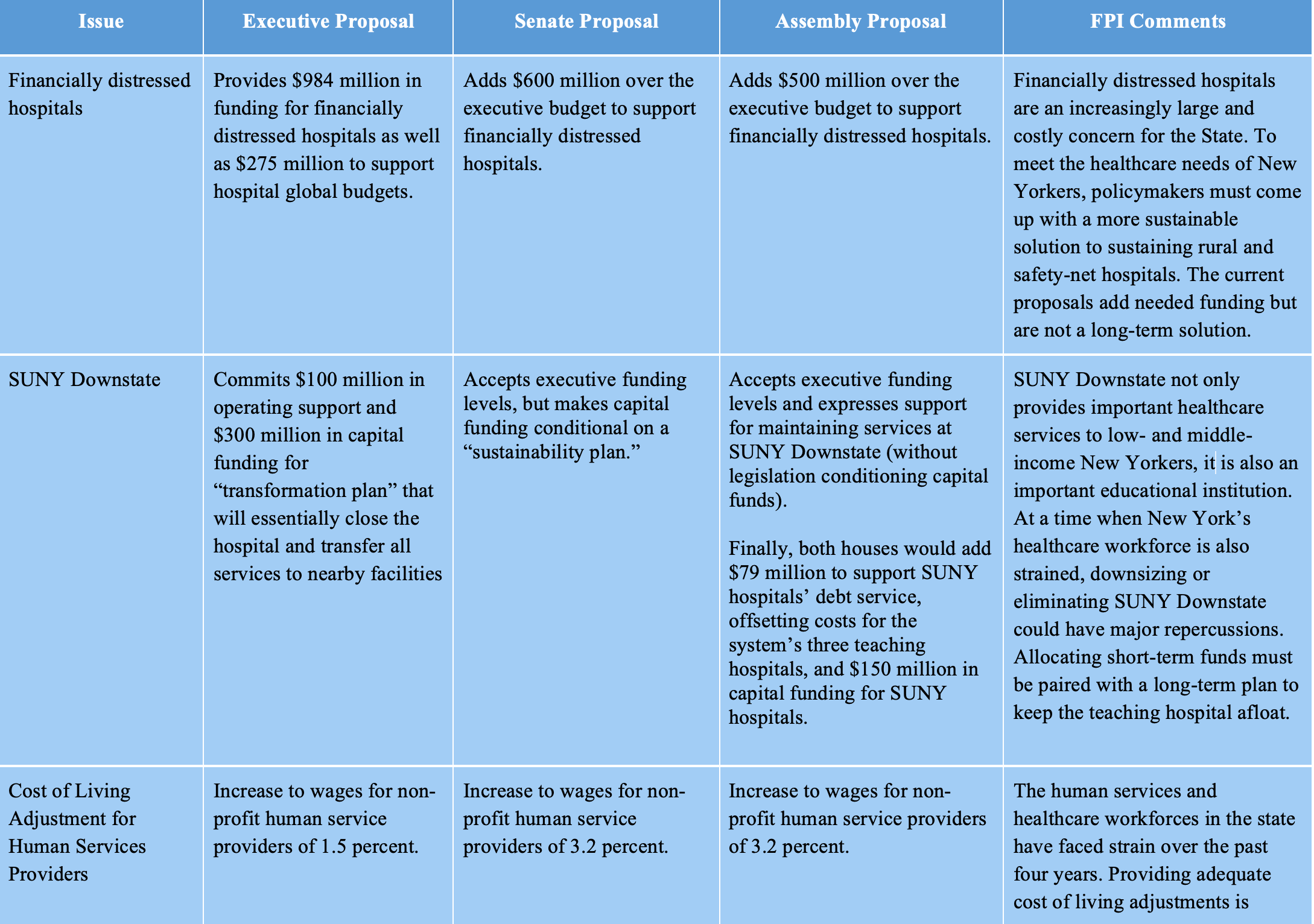

Comparison of executive and legislative budget proposals

The Healthcare Stand-off

March 26, 2024 |

Executive and Legislature at Odds Over Medicaid

Introduction

The one-house budgets reflect a sharp disagreement between the Governor and the legislature on Medicaid spending. The executive budget proposes sharp cuts to several areas of Medicaid spending — most notably home care worker wages — and provides only limited support for financially distressed hospitals.

The Senate and Assembly one-house budgets soundly reject the executive’s approach. Both houses’ budget proposals reject virtually all of the executive budget’s cuts and instead propose substantial rate increases, particularly for hospitals and nursing homes. To pay for their proposals, the one-house budgets propose a new Medicaid tax that would generate $4 billion in additional federal revenue. This proposal represents a smart way to bridge the gap in spending next year and avoid the drastic cuts proposed by the executive; however, in the long term the State must consider more permanent reform and funding mechanisms for its Medicaid program.

Medicaid:

The legislature rejected cuts and proposed significant new funding, resulting in significantly higher Medicaid spending

The Assembly budget proposes $7.1 billion more in state-share Medicaid spending than the executive budget. The Senate’s overall Medicaid spending appears similar. This sum represents by far the largest single difference between the executive budget and the legislature’s proposals. While roughly $3.1 billion of the legislature’s spending would be reinvested to compensate managed care organizations for their payment of the Managed Care Organization Tax (see below), the remaining $4 billion is used to reverse the executive budget’s proposed cuts and offer significant rate increases to providers.

While the executive budget purports to increase Medicaid spending by about $3 billion, this increase in spending is also met by large cuts to home care and nursing care in the state that amount to $1.2 billion. The Senate and Assembly proposals not only reverse these cuts, but also propose to increase Medicaid reimbursement rates across hospitals, nursing homes, and other providers. The gap between the executive budget proposal — which not only fails to raise Medicaid rates but additionally cuts funding — and the Senate and Assembly proposals — which increase spending through rate increases (among other mechanisms) and reverse the executive budget cuts — leaves significant middle ground to be debated.

-

MCO Tax: Legislature proposes an MCO Tax to generate $4 billion in new federal revenue at no cost to New York

As described in a recent FPI brief, the legislature has proposed a Manage Care Organization Tax (MCO Tax) that will generate $4 billion per year in increased federal revenue.[1] This tax will fall primarily on Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs), private insurance plans which administer healthcare for the vast majority of New York’s Medicaid beneficiaries.[2] MCOs will be taxed and then reimbursed by the State for their share of the tax, allowing the state to draw down federal Medicaid matching dollars; the State will generate approximately $7.1 billion in revenue, of which $3.1 billion will be used to reimburse the MCOs, leaving roughly $4 billion in new federal revenue to fund other programs.

This financing structure would need to be approved by the federal government, and receiving such approval would likely take at least six months. Federal regulators recently approved a similar mechanism in California, but indicated that they intend to issue new regulations disallowing it in the future. Thus, the MCO tax proposal faces two forms of uncertainty: In the short term, it is not clear whether the governor will agree to a budget that presumes approval of the MCO tax. In the long term, if the tax is enacted, the State may find that changes in federal regulation render it ineffective in the future and may be forced to seek other sources of revenue.

Despite these uncertainties, the MCO tax provides crucial funding at no cost to New York State taxpayers. Thus, it may serve New York well as a source of funding while longer-term solutions to the State’s healthcare woes are developed.

-

Long-Term Care: The legislature reverses cuts proposed by the executive but does not reform the MLTC program

The cost of providing long-term care to Medicaid recipients is one of the largest drivers of cost increases in the State’s Medicaid budget. As FPI has previously reported, the need for home care has grown tremendously over recent years and will continue to grow as the Baby Boomer generation ages and increases demand for long-term care services.[3]

The executive budget proposes dramatic cuts to the State’s home care system, targeting Consumer-Directed Personal Assistance Program (CDPAP), the largest state home care program, in particular. The executive budget cuts wages for hundreds of thousands of CDPAP workers, imposes a cap on hours, and eliminates “Designated Representatives,” which would likely force tens of thousands of Medicaid beneficiaries out of CDPAP. The one-house budgets reject all of these changes and restore the program to its status quo.

Another site of controversy within the State’s long-term care system has been the Managed Long-Term Care (MLTC) program, which administers much of the state’s Medicaid home care system. Home care advocates and labor unions have argued that this program is wasteful and should be replaced. The executive budget does not adopt this proposal, but suggests more moderate reforms, including competitive procurement of MLTC MCOs and expanded power for the state to enforce MLTC contracts.

The one-house budgets reject the executive budget proposals for MLTC reform, but also decline to heed advocates’ call to eliminate MLTC programs altogether. Both houses included language expressing openness to the elimination of MLTC programs — with the Assembly explicitly calling for a shift away from managed care — but neither house proposes legislation to implement the change. It appears that the MLTC program will remain in limbo for another year, despite broad consensus on the need for reform.

-

Provider Rate Increases and Distressed Hospital Funding: Legislature proposes large increases to hospital and nursing home rates, along with operating and capital support for financially distressed hospitals

The legislature proposes dramatic Medicaid rate increases, heeding calls from provider associations and labor unions for increased funding. Each house includes a 3 percent across-the-board rate hike, plus additional rate increases for hospitals, nursing homes, and assisted living, bringing the total rate increases for those groups to around 10 percent at a cost of around $1.6 billion state share. The one-house budgets also reverse minor cuts to the hospital and nursing home capital rates.

Those rate increases would benefit all hospitals in the state but would not fully address the needs of the many financially distressed hospitals in New York; the executive budget describes nearly a third of the state’s hospitals as financially distressed and suggests billions of dollars in unmet need for operating support. To address this unmet need, the Assembly proposes $500 million in state spending and the Senate proposes $600 million in state operating support for financially distressed hospitals. This funding would likely support some Medicaid spending matched by federal dollars through the Directed Payment Template (DPT) program and some state-only spending through the Vital Access Provider Assurance Program.[4]

Increased operating funds will keep financially distressed hospitals on life support, but it is widely recognized that these hospitals need to invest in improved facilities and new service lines to survive in the long term. The executive budget addresses capital needs by reallocating $500 million in existing capital funding, with the bulk of that apparently intended to support SUNY Downstate’s closure. The capital funding proposed in the executive budget requires financially distressed hospitals to partner with other providers to receive funding. The legislative budgets increase the amount of funding available, with the Assembly providing $1 billion and the Senate proposing $2 billion in additional capital funding; they also drop the requirement that safety net hospitals partner with other institutions to seek funding.

SUNY Downstate: Executive budget proposes closing the hospital while both houses allocate funds towards sustaining it

In January 2024, SUNY announced a plan to close SUNY Downstate, a teaching hospital in Brooklyn. As part of the amended executive budget, the State committed $100 million in operating support and $300 million in capital funding to implement a “transformation plan,” a State-developed plan to relocate certain SUNY Downstate services to the adjacent Kings County Hospital Center, a City-supported hospital.

The Senate and Assembly both accept the executive budget’s proposed spending levels. The Senate, however, would make the capital funding conditional on a “sustainability plan.” The sustainability plan, which would be developed by a commission made up of executive, legislative, labor, and community appointees, would outline a strategy for retaining SUNY Downstate’s teaching and service capacity in five core medical practices defined by the Senate. Operating support would be used to support current services while the sustainability plan is finalized. The Assembly budget resolution expresses support for maintaining services at SUNY Downstate, though it does not include legislation conditioning capital funds.

Finally, both houses would add $79 million to support SUNY hospitals’ debt service, offsetting costs for the system’s three teaching hospitals, and $150 million in capital funding for SUNY hospitals.

Human Services Providers: Legislature proposes a significantly higher rate increase than the Executive

While the executive budget proposed an increase to the wages of 1.5 percent for non-profit human service providers, the Senate and Assembly both proposed a larger wage increase of 3.2 percent. Against the backdrop of inflation over the past three years, this cost of living adjustment is relatively small and may not do much to retain staff.

Conclusion

The legislature is wise to reject the Governor’s cuts to Medicaid and has identified a viable source of new federal revenue to support continued Medicaid growth. However, the legislature has missed an opportunity to reform New York’s home care delivery system by eliminating Managed Long Term Care and substituting a Managed Fee-for-Service arrangement, a move that could save the State billions of dollars. In addition, the legislature has not articulated a clear long-term vision for the role of safety-net hospitals and the best way to financially support them; in the absence of such a vision, increased funding is welcome, but the drumbeat of hospital closures will likely continue.

[1] https://fiscalpolicy.org/the-medicaid-mco-tax-strategy

[2] It is important to note that the state operates several Medicaid managed care programs, the largest of which (“Mainstream Managed Care”) provides Medicaid benefits to the vast majority of New York’s Medicaid beneficiaries. A smaller but expensive program, “Managed Long-Term Care,” provides home care to elderly and disabled New Yorkers. The MLTC program has been controversial, with advocates and labor unions calling for the elimination of MLTC MCOs. However, the MCO tax would likely generate most of its revenue from the Mainstream Managed Care program and would be a viable revenue option even if the MLTC program were eliminated.

[3] https://fiscalpolicy.org/workforce-report-labor-shortage-mitigation-in-new-yorks-home-care-sector

[4] See discussion at Step Two Policy Project https://22bd584a-fab4-4177-ba23-ab0417da452c.usrfiles.com/ugd/22bd58_824ee45ce42a41cabf287bd2f4aaa935.pdf

Comparison of executive and legislative budget proposals